Power Struggle in Iran

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iran News Update September 2017

September 2017 Politics: In an address to the joint strategy committee of Iran- Japan in Tehran, Masoumeh Ebtekar called for enhancing Iran’s parliament offered a vote of confidence to all the role of women in promoting peace and security in nominated ministers except for Habibollah Bitaraf, who the international arena. had previously served under a reformist administration. Demonstrations have been carried out in Baneh, in the Mohammad Javad Zarif was confirmed as Iran’s Foreign Kurdistan Province of Iran, to protest the deaths of two Minister for a second term. Zarif stated that Iran’s foreign Kurdish cross border carriers. The demonstrations led affairs will focus on boosting economic relations with its to violence and several arrests were made by Iranian neighbouring countries. authorities. Iranian President Hassan Rouhani appointed Mohammed Mohsen Hojaji, an Iranian military advisor in Syria, was Nahavndian as the new Vice-President for Economic taken hostage and beheaded by the Islamic State group Affairs. In another decree, highly experienced Mahmoud in Syria. Vaezi was appointed Rouhani’s new Chief of Staff. International Relations: Three women have been appointed vice presidency positions in President Rouhani’s new cabinet. Head of Iran-Australia Parliamentary Friendship Group Mahmoud Sadeqi met with Australian Ambassador to Mohammad-Ali Najafi, Iran’s ex-minister from the Iran Ian Biggs in Tehran. Ambassador Biggs stated that reformist camp, has been elected Tehran’s new mayor Canberra strongly supports the landmark nuclear deal with the votes of Tehran city council. and considers it an opportunity to establish peace in the region. Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei appointed Ayatollah Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi, the ex-Chief The head of Iran-Britain Parliamentary Friendship Group Justice of Iran, as the new Chairman of Iran’s Expediency announced that British delegates are planning to travel Council. -

Implementation of the NPT Safeguards Agreement in Iran For

Atoms for Peace Board of Governors GOV/2015/65 Date: 18 November 2015 Restricted Distribution Original: English For official use only Item 5(c) of the provisional agenda (GOV/2015/63) Implementation of the NPT Safeguards Agreement and relevant provisions of Security Council resolutions in the Islamic Republic of Iran Report by the Director General Main Developments On 20 September 2015, the Director General held talks with President Rouhani, Vice-President Salehi and Foreign Minister Zarif, on the implementation of the Road-map. They also exchanged views on issues related to the implementation by Iran of its nuclear-related commitments under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). In addition, the Director General met members of the Iranian Parliament. On 20 September 2015, the Director General and the Deputy Director General for Safeguards visited the particular location at the Parchin site of interest to the Agency. Environmental samples were taken in the days immediately prior to the visit. The activities set out in the Road-map for the period to 15 October 2015 have been completed on schedule. On 18 October 2015, Iran informed the Agency that, effective on JCPOA Implementation Day, Iran will provisionally apply the Additional Protocol to its Safeguards Agreement and fully implement the modified Code 3.1. On 18 October 2015, the Adoption Day of the JCPOA was reached. The Agency has begun conducting preparatory activities related to the verification and monitoring of Iran’s nuclear-related commitments under the JCPOA, including verification and monitoring of the steps Iran has begun taking towards the implementation of those commitments. -

The Relationship Between the Supreme Leadership and Presidency and Its Impact on the Political System in Iran

Study The Relationship Between the Supreme Leadership and Presidency and Its Impact on the Political System in Iran By Dr. Motasem Sadiqallah | Researcher at the International Institute for Iranian Studies (Rasanah) Mahmoud Hamdi Abualqasim | Researcher at the International Insti- tute for Iranian Studies (Rasanah) www.rasanah-iiis.org WWW.RASANAH-IIIS.ORG Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................... 3 I- The Status and Role of the Supreme Leadership and the Presidency in the Iranian Political System ................................................................................. 4 II- The Problems Involving the Relationship Between the Supreme Leader and the Presidency .............................................................................................. 11 III- Applying Pressure Through Power to Dismiss the President .....................15 IV- The Implications of the Conflict Between the Supreme Leader and the Presidency on the Effectiveness of the Political System ................................. 20 V- The Future of the Relationship Between the Supreme Leader and the President ........................................................................................ 26 Conclusion .................................................................................................. 29 Disclaimer The study, including its analysis and views, solely reflects the opinions of the writers who are liable for the conclusions, statistics or mistakes contained therein -

Congress of Vienna Program Brochure

We express our deep appreciation to the following sponsors: Carnegie Corporation of New York Isabella Ponta and Werner Ebm Ford Foundation City of Vienna Cultural Department Elbrun and Peter Kimmelman Family Foundation HOST COMMITTEE Chair, Marifé Hernández Co-Chairs, Gustav Ortner & Tassilo Metternich-Sandor Dr. & Mrs. Wolfgang Aulitzky Mrs. Isabella Ponta & Mr. Werner Ebm Mrs. Dorothea von Oswald-Flanigan Mrs. Elisabeth Gürtler Mr. & Mrs. Andreas Grossbauer Mr. & Mrs. Clemens Hellsberg Dr. Agnes Husslein The Honorable Andreas Mailath-Pokorny Mr. & Mrs. Manfred Matzka Mrs. Clarissa Metternich-Sandor Mr. Dominique Meyer DDr. & Mrs. Oliver Rathkolb Mrs. Isabelle Metternich-Sandor Ambassador & Mrs. Ferdinand Trauttmansdorff Mrs. Sunnyi Melles-Wittgenstein CONGRESS OF VIENNA 2015 | 2 Presented by the The CHUMIR FOUNDATION FOR ETHICS IN LEADERSHIP is a non-profit foundation that seeks to foster policies and actions by individuals, organizations and governments that best contribute to a fair, productive and harmonious society. The Foundation works to facilitate open-minded, informed and respectful dialogue among a broad and engaged public and its leaders to arrive at outcomes for a better community. www.chumirethicsfoundation.ca CONGRESS OF VIENNA 2015 | 2 CONGRESS OF VIENNA 2015 | 3 CONGRESS OF VIENNA 2015 | 4 UNDER THE DISTINGUISHED PATRONAGE OF H.E. Heinz Fischer, President of the Republic of Austria HONORARY CO-CHAIRS H.E. Josef Ostermayer Minister of Culture, Media and Constitution H.E. Sebastian Kurz Minister of Foreign Affairs and Integration CHAIR Joel Bell Chairman, Chumir Foundation for Ethics in Leadership CONGRESS SECRETARY Manfred Matzka Director General, Chancellery of Austria CHAIRMAN INTERNATIONAL ADVISORY COUNCIL Oliver Rathkolb HOST Chancellery of the Republic of Austria CONGRESS OF VIENNA 2015 | 4 CONGRESS OF VIENNA 2015 | 5 CONGRESS OF VIENNA 2015 | 6 It is a great honor for Austria and a special pleasure for me that we can host the Congress of Vienna 2015 in the Austrian Federal Chancellery. -

Petroleum: an Engine for Global Development

OPEC th International Seminar Petroleum: An Engine for Global Development 3–4 June 2015 Hofburg Palace Vienna, Austria www.opec.org Reasons to be cheerful It was over quite quickly. In fact, the 165th Meeting whilst global oil demand was expected to rise from of the OPEC Conference finished two hours ahead of 90m b/d to 91.1m b/d over the same period. In ad- Commentary schedule. Even the customary press conference, held dition, petroleum stock levels, in terms of days of for- immediately after the Meeting at the Organization’s ward demand cover, remained comfortable. “These Secretariat in Vienna, Austria on June 11 and usually numbers make it clear that the oil market is stable and a busy affair, was most probably completed in record balanced, with adequate supply meeting the steady time. But this brevity of discourse spelled good news growth in demand,” OPEC Conference President, Omar — for OPEC and, in fact, all petroleum industry stake- Ali ElShakmak, Libya’s Acting Oil and Gas Minister, holders. As the much-heralded saying goes — ‘don’t be said in his opening address to the Conference. tempted to tamper with a smooth-running engine’. And Of course, there are still downside risks to the glob- that is exactly what OPEC’s Oil and Energy Ministers al economy, both in the OECD and non-OECD regions, did during their customary mid-year Meeting. They de- and there is continuing concern over some production cided to leave the Organization’s 30 million barrels/ limitations, but with non-OPEC supply growth of 1.4m day oil production ceiling in place and unchanged for b/d forecast over the next year, in general, things are the remainder of 2014. -

OPEC Petroleum

OPEC th International Seminar Petroleum: An Engine for Global Development 3–4 June 2015 Hofburg Palace Vienna, Austria Contact: 50 +44 7818 598178 www.opecseminar.org [email protected] OPEC International Seminar: Advocating oil market dialogue Commentary On June 3, 2015, Austria’s famous Hofburg Palace will once again sessions which will cover a range of topical subjects that will in- open its doors to OPEC’s International Seminar. The stately building, clude global energy outlooks, oil market stability, production ca- which dates back to the 13th century, will host what promises to be pacity and investment, technology and the environment, and pros- two days of intense and lively discussion on the global oil sector. It pects for the world economy. is a striking and most fitting venue. As the former imperial residence Clearly, with so much uncertainty surrounding the interna- of the Habsburg dynasty, rulers of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, tional oil market today, high-level international energy fora such the Hofburg has been home to some of the most powerful people as the OPEC Seminar are essential for addressing the main issues in European and Austrian history. Today, part of the Palace forms and helping overcome the many challenges that exist. Striving for the official residence and workplace of the President of Austria. oil market equilibrium and limiting harmful price volatility have Throughout the annual calendar, the Hofburg also stages over been central to OPEC’s cause since the Organization’s formation 300 events — events, such as the OPEC Seminar. This will be the in 1960. And this overriding commitment to stability is why the fourth time the Organization, which has had its Headquarters in the Organization and its Member Countries have made repeated calls Austrian capital since 1965, has chosen to convene its International for cooperation among the principle energy industry stakeholders. -

2 8 Hi 1 3 COUNTRY PROGRAMME EVALUATION REVIEW- IRAN

XA9743980 INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY COUNTRY PROGRAMME EVALUATION REVIEW THE AGENCY'S TECHNICAL CO-OPERATION PROGRAMME IN THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF IRAN 1982-1995 EVALUATION SECTION DEPARTMENT OF TECHNICAL CO-OPERATION IAEA-CPE-96/01 July 1996 Original: ENGLISH 2 8 Hi 1 3 COUNTRY PROGRAMME EVALUATION REVIEW- IRAN TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 1.2 REASONS FOR THE EVALUATION 1.3 STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT 2. AGENCY TC ACTIVITIES IN IRAN (1982-1995) 3. DESCRIPTION OF THE EVALUATION 3.1 THE EVALUATION PROCESS 3.1.1 Preparation of Background Information 3.1.2 Field Evaluation 3.2 COMPOSITION OF THE EVALUATION TEAM 3.3 LIMITATIONS OF THE EVALUATION 3.4 THE ASSESSMENT SYSTEM 4. FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 4.1 PROGRAMME SPECIFIC FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 4.1.1 Nuclear Power Programme 4.1.2 Human Health 4.1.3 Health Physics 4.1.4 Industrial Applications 4.1.5 Mineral Resources 4.1.6 Research Reactors 4.1.7 Isotope Hydrology 4.1.8 Analytical Techniques 4.1.9 Agriculture 4.1.10 General Atomic Energy Development 4.2 OVERALL PROGRAMME ASSESSMENT 4.3 SUGGESTIONS FOR FUTURE TECHNICAL CO-OPERATION WITH IRAN _________ COUNTRY PROGRAMME EVALUATION REVIEW - IRAN ANNEXES A: TERMS OF REFERENCE B: TC PROJECT SUMMARIES AND INPUTS B. 1 Nuclear Power Programme B.2 Human Health B. 3 Health Physics B. 4 Industrial Applications B. 5 Mineral Resources B. 6 Research Reactors B. 7 Isotope Hydrology B. 8 Analytical Techniques B. 9 Agriculture B. 10 General Atomic Energy Development C: ECONOMIC AND SCIENTIFIC INFRASTRUCTURE IN IRAN D: NATIONAL ORGANIZATION OF NUCLEAR ACTIVITIES IN IRAN E: EVALUATION TIMETABLE F: LIST OF PEOPLE MET IAEA-CPE-96/01 COUNTRY PROGRAMME EVALUATION REVIEW - IRAN List of Abbreviations AEOI: Atomic Energy Organization of Iran BNPP: Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant GIC: Gamma Irradiation Centre, Teheran NRCAM: Nuclear Research Centre for Agriculture and Medicine, Karadj NRC: Nuclear Research Centre, Teheran ENTC: Esfahan Nuclear Technology Centre m/d: months/days of expert services. -

NPT Safeguards Agreement with the Islamic Republic of Iran

Derestricted 17 September 2020 (This document has been derestricted at the meeting of the Board on 17 September 2020) Atoms for Peace and Development Board of Governors GOV/2020/47 Date: 4 September 2020 Original: English For official use only Item 9 (d) of the provisional agenda (GOV/2020/36) NPT Safeguards Agreement with the Islamic Republic of Iran Wit Report by the Director General A. Introduction 1. This report of the Director General is on the implementation of the NPT Safeguards Agreement1 and the Additional Protocol thereto2 in the Islamic Republic of Iran (Iran). It describes the Agency’s efforts and interactions with Iran to clarify information relating to the correctness and completeness of Iran’s declarations under its Safeguards Agreement and Additional Protocol. B. Evaluation of safeguards-relevant information 2. The comprehensive evaluation of all safeguards-relevant information available to the Agency is essential in ascertaining that there are no indications of diversion of declared nuclear material from peaceful nuclear activities and that there are no indications of undeclared nuclear material and activities in a State with a comprehensive safeguards agreement.3 __________________________________________________________________________________ 1 The Agreement between Iran and the Agency for the Application of Safeguards in Connection with the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (INFCIRC/214), which entered into force on 15 May 1974. 2 Iran’s Additional Protocol (INFCIRC/214/Add.1) was approved by the Board of Governors on 21 November 2003 and signed by Iran on 18 December 2003. Iran implemented voluntarily the Additional Protocol between December 2003 and February 2006. -

Iran News Update February 2017

February 2017 Politics: Ali Larijani and Ali Akbar Velayati met with Iraqi Vice President Nouri al-Maliki. At the meeting al-Maliki Chairman of the Expediency Council Ayatollah Akbar praised Iran for its anti-terrorism campaign in the region. Hashemi Rafsanjani passed away at the age 82 due to heart conditions. Rafsanjani was one of the most Iran objected to the United States participation at the influential political figures in the post-revolution period. Syria peace talks in Kazakhstan. The following week the Huge crowds of mourners poured into streets of Tehran United States sent only its Kazakhstan ambassador to the to take part in his funeral ceremony. talks. Iran’s oldest high rise building Plasco collapsed following Iranian officials confirmed that Saudi Arabia had offically a major fire in the building. Many firefighters and invited Iran to attend bilateral talks regarding the next civilians were killed and injured. annual Hajj pilgrimage. The first and only female Minister in Iran Marziyeh Vahid- Chairman of the Iranian Parliament Committee on Dastjerdi denied speculations that she will be running in National Security and Foreign Policy Alaeddin Boroujerdi the next Iranian presidential elections. met with Lebanese President Michel Aoun in Beirut. They discussed enhancing Iranian – Lebanese relations The Vice President of Iran in the cabinet of President in the fields of trade, economics and security. Boroujerdi Hassan Rouhani in the section of Women and Family later expressed that Iran was determined to offer military Affairs, Shahindokht Molaverdi, announced that the aid to Lebanon. women’s social security plan had been submitted to the Ministry of Interior for final approval. -

Road-Map for the Clarification of Past and Present Outstanding Issues Regarding Iran’S Nuclear Programme

Derestricted 21 September 2015 (This document has been derestricted at the meeting of the Board on 21 September 2015) Atoms for Peace Board of Governors GOV/2015/59 Date: 21 September 2015 Original: English For official use only Item 4 of the provisional agenda (GOV/2015/56/Rev.2) Road-map for the Clarification of Past and Present Outstanding Issues regarding Iran’s Nuclear Programme Report of the Director General A. Introduction 1. This report provides an update, since the Director General’s previous report,1 on the implementation of the ‘Road-map for the clarification of past and present outstanding issues regarding Iran’s nuclear programme’ (Road-map) agreed between the Agency and Iran on 14 July 2015,2 aimed at the resolution, by the end of 2015, of all past and present outstanding issues that have not already been resolved by the Agency and Iran. B. Recent Developments 2. As previously reported, as agreed in the Road-map, Iran provided to the Agency its explanations in writing and related documents, on the outstanding issues on 15 August 2015.3 The Agency reviewed this information and submitted to Iran questions on the ambiguities contained therein on 8 September 2015.4 __________________________________________________________________________________ 1 GOV/2015/50. 2 GOV/INF/2015/14. 3 GOV/2015/50, para.8. 4 Note by Secretariat (2015/Note 69, 8 September 2015). GOV/2015/59 Page 2 3. As also agreed in the Road-map, the Agency and Iran have held technical-expert meetings and discussions in Tehran to remove the ambiguities. Further meetings are planned prior to 15 October 2015, the date in the Road-map by which the activities aimed at resolving past and present outstanding issues are to be completed. -

Oil Rail & Ports Conference Programme at a Glance

OIL RAIL & PORTS CONFERENCE PROGRAMME AT A GLANCE DAY ONE, 15 MAY 2016 09.00-10.30 Opening Remarks & Patron Welcome • Mr. Eshaq Jahangiri, Vice President of Iran • Mr. Bijan Namdar Zangeneh, Minister of Petroleum Iran • Mr. Abbas Ahmad Akhoundi, Minister of Transport Iran • Dr. Mohesen Pour Seyed Aghaie, Vice Minister Road and Urban Development, President of RAI • Mr. Jean-Pierre Loubinoux, Director General UIC • Mr. Francois Davenne, Secretary General OTIF (Intergovernmental Organisation for International Carriage by Rail 10.30 -12.00 The Challenges of Keeping Position in a Fast Changing Environment. Presented by Mr. Armand Toubol, Honorary Deputy Director General, SNCF Overview. This presentation will give an overview of the global vessel evolution, the intermodal market and port infrastructure development including success stories and best practices from cargo owners around the globe. About. SNCF is France's national state-owned railway company and manages the rail traffic in France. SNCF operates the country's national rail services, including the TGV, France's high- speed rail network. 12.00-14.00 Executive Networking Luncheon and RailExpo Exhibition Visit 14.00-15.00 Investment Opportunities Created by the Present Environment of Low Global Oil and Gas Prices Presented by Mr. Ed Osterwald, Senior Partner, Competition Economists Group (CEG Europe) Overview. There are many fallacies associated with the oil and gas industry. For one, low prices may cause difficulties for some participants but can also create amazing opportunities. Likewise and contrary to popular opinion, there is no such thing as a “fossil fuel.” Also contrarily to many: hydrocarbon fuels will continue to power the world for the foreseeable future. -

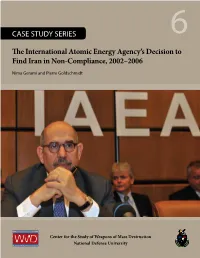

IAEA Decision to Find Iran in Non-Compliance, 2002–2006

CASE STUDY SERIES 6 The International Atomic Energy Agency’s Decision to Find Iran in Non-Compliance, 2002–2006 Nima Gerami and Pierre Goldschmidt Center for the Study of Weapons of Mass Destruction National Defense University Center for the Study of Weapons of Mass Destruction National Defense University DR. JOHN F. REICHART Director DR. W. SETH CARUS Deputy Director, Distinguished Research Fellow Since its inception in 1994, the Center for the Study of Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD Center) has been at the forefront of research on the implications of weapons of mass destruction for U.S. security. Originally focusing on threats to the military, the WMD Center now also applies its expertise and body of research to the challenges of homeland security. The center’s mandate includes research, education, and outreach. Research focuses on understanding the security challenges posed by WMD and on fashioning effective responses thereto. The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff has designated the center as the focal point for WMD education in the joint professional military education system. Education programs, including its courses on countering WMD and consequence management, enhance awareness in the next generation of military and civilian leaders of the WMD threat as it relates to defense and homeland security policy, programs, technology, and operations. As a part of its broad outreach efforts, the WMD Center hosts annual symposia on key issues bringing together leaders and experts from the government and private sectors. Visit the center online at www.ndu.edu/WMDCenter/. Cover: IAEA Director General Mohamed ElBaradei before start of regular Board of Governors meeting, Vienna, June 15, 2009.