A New Approach for Allocating a New Party's Budget During an Election Campaign Irit Talmor1 2 and Osnat Akirav3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2013

ANNUAL 2013 REPORT BATSHEVA DANCE COMPANY 1 PAGE 0 PAGE Dear friends, Dear friends, In 2013, Batsheva continued its creative momentum. The pinnacle was Ohad Naharin's In the continuous flow of processes and progress, the call to summarize the year new creation, The Hole, in which he proved once again his innovative choreographic offers an opportunity to pause and look back. voice. This fascinating, unique creation won the audience’s heart and also received warm critical praise. In addition, within Batsheva's commitment to encourage and 2013 was full of significant creative processes in the studio and warm dialogue with nurture emerging talent, the Ensemble presented Shula by young choreographer the audience both in Israel and abroad. It was a year of evolution and profundity, Danielle Agami, and this piece, too, won great success. with many moments of beauty and quality. Approximately 94,000 people attended the Company's performances during 2013. The Company toured extensively around the world and held 51 performances for The year's accomplishments belong to everyone – the dancers who shone in their 36,000 spectators abroad, strengthening the Company's international reputation. work; the artistic team, the administration, and the technical crew who devoted Once again the Company was an excellent ambassador for Israel. themselves to creation with passion and inspired joy; the public council members The Company pursued its social and educational activity in Israel. In its series of and the board of directors who accompany us with involvement and love; the morning school shows, a tradition Batsheva has maintained for over a decade, the benefactors who believe in us and who enable us to excel; and the wide audience Ensemble performed for 10,000 students in cities across Israel. -

Dorit Tubin Associate Professor, Department of Education, Ben

Dorit Tubin Curriculum Vitae Associate Professor, Department of Education, Ben Gurion University of the Negev P.O. Box 653, Beer Sheva, 84105, Israel; [email protected]; 972-8-646-1870 (phone); 972-8-647-2897 (fax) Education 1982-1985 B.A. Behavioral Science, (BGU), with Honors 1985-1989 M.A. Sociology of Organizations, BGU, with Honors, 1998 Fulbright research fellowship, Harvard University, Graduate School of Education (HGSE). 1994 - 1999 Ph.D. Education, Tel Aviv University Employment History 2016 -Present Associate Professor, Department of Education, BGU 2012-2013 Visiting scholar- sabbatical leave, Department of Educational Leadership and Higher Education, Lynch School of Education, Boston College, MA. 2010 - 2016 Senior lecturer, Department of Education, (BGU) 2004 - 2010 Lecturer, Department of Education, BGU 2002 - 2004 Instructor, Department of Education, BGU 2001 - 2002 Postdoctoral Researcher, School of Education, Tel Aviv University 1999 - 2002 Adjunct Lecturer, Faculty of Education, Haifa University 1999 - 2002 Research coordinator for innovational planning and "School of the Future" projects, Tel Aviv University, School of Education, Israel 1997 - 2002 Educational planner and organizational advisor, Self-employed 1994 - 1998 Administrative Manager, Aurec Information Ltd., Ramat-Gan 1993 - 1994 Evaluator in a project for introducing computers into kindergartens, Ministry of Education, Israel 1989 - 1993 National coordinator of “Horim”, an educational outreach program Ministry of Education, Israel 1984 - 1988 Research and teaching assistant, Department of Behavioral Science, BGU 1980 - 1981 Israel Government employee, London Professional Activities (a) Positions in academic administration 2015 - Present Chair, Department of Education, BGU 2010 - Present Head of principal preparation program - Department of Education, BGU 2008 - 2012 Head of the Center for Promotion of professionalism in Education - Department of Education, BGU 2006 - 2008 Member of the B.A. -

Forgotten Palestinians

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 THE FORGOTTEN PALESTINIANS 10 1 2 3 4 5 6x 7 8 9 20 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 30 1 2 3 4 5 36x 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 20 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 30 1 2 3 4 5 36x 1 2 3 4 5 THE FORGOTTEN 6 PALESTINIANS 7 8 A History of the Palestinians in Israel 9 10 1 2 3 Ilan Pappé 4 5 6x 7 8 9 20 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 30 1 2 3 4 YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS 5 NEW HAVEN AND LONDON 36x 1 In memory of the thirteen Palestinian citizens who were shot dead by the 2 Israeli police in October 2000 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 4 5 Copyright © 2011 Ilan Pappé 6 The right of Ilan Pappé to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by 7 him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. 8 All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright 9 Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from 20 the publishers. 1 For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, 2 please contact: U.S. -

Return of Organization Exempt from Income

Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Form 990 Under section 501 (c), 527, or 4947( a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung benefit trust or private foundation) 2005 Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service ► The o rganization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state re porting requirements. A For the 2005 calendar year , or tax year be and B Check If C Name of organization D Employer Identification number applicable Please use IRS change ta Qachange RICA IS RAEL CULTURAL FOUNDATION 13-1664048 E; a11gne ^ci See Number and street (or P 0. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number 0jretum specific 1 EAST 42ND STREET 1400 212-557-1600 Instruo retum uons City or town , state or country, and ZIP + 4 F nocounwro memos 0 Cash [X ,camel ded On° EW YORK , NY 10017 (sped ► [l^PP°ca"on pending • Section 501 (Il)c 3 organizations and 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trusts H and I are not applicable to section 527 organizations. must attach a completed Schedule A ( Form 990 or 990-EZ). H(a) Is this a group return for affiliates ? Yes OX No G Website : : / /AICF . WEBNET . ORG/ H(b) If 'Yes ,* enter number of affiliates' N/A J Organization type (deckonIyone) ► [ 501(c) ( 3 ) I (insert no ) ] 4947(a)(1) or L] 527 H(c) Are all affiliates included ? N/A Yes E__1 No Is(ITthis , attach a list) K Check here Q the organization' s gross receipts are normally not The 110- if more than $25 ,000 . -

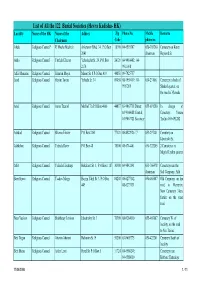

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No. Mobile Remarks Chairman Code phone no. Afula Religious Council* R' Moshe Mashiah Arlozorov Blvd. 34, P.O.Box 18100 04-6593507 050-303260 Cemetery on Keren 2041 chairman Hayesod St. Akko Religious Council Yitzhak Elharar Yehoshafat St. 29, P.O.Box 24121 04-9910402; 04- 2174 9911098 Alfei Menashe Religious Council Shim'on Moyal Manor St. 8 P.O.Box 419 44851 09-7925757 Arad Religious Council Hayim Tovim Yehuda St. 34 89058 08-9959419; 08- 050-231061 Cemetery in back of 9957269 Shaked quarter, on the road to Massada Ariel Religious Council Amos Tzuriel Mish'ol 7/a P.O.Box 4066 44837 03-9067718 Direct; 055-691280 In charge of 03-9366088 Central; Cemetery: Yoram 03-9067721 Secretary Tzefira 055-691282 Ashdod Religious Council Shlomo Eliezer P.O.Box 2161 77121 08-8522926 / 7 053-297401 Cemetery on Jabotinski St. Ashkelon Religious Council Yehuda Raviv P.O.Box 48 78100 08-6714401 050-322205 2 Cemeteries in Migdal Tzafon quarter Atlit Religious Council Yehuda Elmakays Hakalanit St. 1, P.O.Box 1187 30300 04-9842141 053-766478 Cemetery near the chairman Salt Company, Atlit Beer Sheva Religious Council Yaakov Margy Hayim Yahil St. 3, P.O.Box 84208 08-6277142, 050-465887 Old Cemetery on the 449 08-6273131 road to Harzerim; New Cemetery 3 km. further on the same road Beer Yaakov Religious Council Shabbetay Levison Jabotinsky St. 3 70300 08-9284010 055-465887 Cemetery W. -

RENANA SAMUELOV – JINDI ASSOCIATE, URBAN PLANNING DEPARTMENT MANAGER Education B.Sc

RENANA SAMUELOV – JINDI ASSOCIATE, URBAN PLANNING DEPARTMENT MANAGER Education B.Sc. from The Hebrew University, Geography and Islamic Studies (1996) MA from The Hebrew University, Geography and Urban and Regional Planning (1999) Key Data HaCharash Street Complex – Holon Hayeruka, Israel Renana joined MOORE Architects La Guardia, Israel UPB special housing, commercial, in 2004. Has 18 years experience in UBP for business and commerce, public buildings and urban planning. Renana independently Tel Aviv institutions, Holon manages the urban planning team in the office that simultaneously handles about MAAR Ganei Tikva, Israel Ness Tziona Commercial 70 UBPs in various stages of progress. UBP for business, commerce and Center, Israel Renana is responsible for promotion residential center, Ganei Tikva UBP commerce, business, public buildings and institutions, Ness Tziona and management of UBP on all levels Bar-Ilan Intersection, Israel and in every sphere of planning, from UBP for business, commerce and Hof Hatchelet Complex, North data processing to prepare the plan residence, Kiryat Ono Glilot, Israel to preparation of the plan documents, UBP for business and commerce, coordination of planning with various Shenkar-Jabotisnky Complex, Israel Ramat Hasharon parties, appearances before the UBP for business and commerce, Planning Committee to final approval of Petah Tikva Hof Hatzuk, Israel the plan. Simultaneous with the work on UBP for hotels and residence, Tel Aviv the plan, the client is given advice Shlomo Hamelech Complex, Israel on the -

Leading Teachers As Agents of Improvement in the Education System

Activity report by the steering committee chaired by Prof. Miriam Ben-Peretz and Prof. Lee Shulman Leading Teachers as Agents of Improvement in the Education System Based on recommendations by the roundtable chaired by Dr. Nir Michaeli Coordinated and edited by Orit Sommer Translated from the Hebrew original Applied Education Research Applied Education עיצוב עטיפה: Activity report by the steering committee chaired by Prof. Miriam Ben-Peretz and Prof. Lee Shulman Leading Teachers as Agents of Improvement in the Education System Based on recommendations by the roundtable chaired by Dr. Nir Michaeli Coordinated and edited by Orit Sommer Translated from the Hebrew original August 2014 The Initiative for Applied Education Research The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities Jerusalem, 5774, 2014 The Initiative for Applied Education Research The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities Linguistic editor (of the Hebrew origin): Ada Paldor Translation: Ira Moskowitz Production and proofreading: Reut Issachar Graphic design: Esti Boehm Cover design: Rami and Jacky Studio ISBN: 978-965-7601-05-1 The document is published by the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities and is available to the public at http://education.academy.ac.il, subject to copyright attribution for non-commercial use (CC-BY-NC-SA), not including translation rights. In any use of this document or quotation from it, the source should be cited as follows: Michaeli, N., Sommer, O. (eds.) (2014). Activity report by the steering committee chaired by Prof. Miriam Ben-Peretz and Prof. Lee Shulman: Leading Teachers as Agents of Improvement in the Education System, Jerusalem: The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities. -

Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Over Palestine

Metula Majdal Shams Abil al-Qamh ! Neve Ativ Misgav Am Yuval Nimrod ! Al-Sanbariyya Kfar Gil'adi ZZ Ma'ayan Baruch ! MM Ein Qiniyye ! Dan Sanir Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid over Palestine Al-Sanbariyya DD Al-Manshiyya ! Dafna ! Mas'ada ! Al-Khisas Khan Al-Duwayr ¥ Huneen Al-Zuq Al-tahtani ! ! ! HaGoshrim Al Mansoura Margaliot Kiryat !Shmona al-Madahel G GLazGzaGza!G G G ! Al Khalsa Buq'ata Ethnic Cleansing and Population Transfer (1948 – present) G GBeGit GHil!GlelG Gal-'A!bisiyya Menara G G G G G G G Odem Qaytiyya Kfar Szold In order to establish exclusive Jewish-Israeli control, Israel has carried out a policy of population transfer. By fostering Jewish G G G!G SG dGe NG ehemia G AGl-NGa'iGmaG G G immigration and settlements, and forcibly displacing indigenous Palestinians, Israel has changed the demographic composition of the ¥ G G G G G G G !Al-Dawwara El-Rom G G G G G GAmG ir country. Today, 70% of Palestinians are refugees and internally displaced persons and approximately one half of the people are in exile G G GKfGar GB!lGumG G G G G G G SGalihiya abroad. None of them are allowed to return. L e b a n o n Shamir U N D ii s e n g a g e m e n tt O b s e rr v a tt ii o n F o rr c e s Al Buwayziyya! NeoG t MG oGrdGecGhaGi G ! G G G!G G G G Al-Hamra G GAl-GZawG iyGa G G ! Khiyam Al Walid Forcible transfer of Palestinians continues until today, mainly in the Southern District (Beersheba Region), the historical, coastal G G G G GAl-GMuGftskhara ! G G G G G G G Lehavot HaBashan Palestinian towns ("mixed towns") and in the occupied West Bank, in particular in the Israeli-prolaimed “greater Jerusalem”, the Jordan G G G G G G G Merom Golan Yiftah G G G G G G G Valley and the southern Hebron District. -

Israeli Water Technology Company Directory™

ISRAELI WATER TECHNOLOGY COMPANY DIRECTORY Compiled by The Negev Foundation Ohio-Israel Ag & CleanTech Initiative 2121 South Green Road Cleveland, OH 44121 216-691-9997 www.ohioisrael.org Ver. 2 – Jan. 2019 Israeli Water Technology Companies 1 A.A. Engineers Environmental & Agricultural Engineering P.O. Box 1360 Services Offered Kiryat Tivon, Israel 36000 +972-4-993-0049 A.A. Engineers is a consulting firm established in 1982 specializing in wastewater treatment, solid waste systems, www.aaengineers.co.il agricultural and environmental consulting. Amitay Avnon, Director They specialize in an environmentally-friendly, biological wastewater treatment system called Constructed Wetlands [email protected] as an ecological solution for sanitary wastewater, industrial and agricultural wastewaters. Admir Environment 24 HaTa'asiya Street Services Offered Yehud, Israel 5621804 +972-3-536-6646 Marine dredging using a DREDGER. Sludge dewatering by means of Geotube®. Fuel tanks and industrial tanks www.admir.co.il cleaning. Sludge dewatering at Municipal WWTP. Rivers clean up and water treatment sedimentation. Hemi Tamari, Marketing Manager [email protected] Israeli Water Technology Companies 2 A.G.M. Communication and Control Ltd. Mitzpe, Services Offered Lower Galilee, 1527600, Israel +972-4-677-4754 / 55 AGM is a provider of smart Communication and Control solutions for SCADA and DCS systems, with 30 years of www.agm.co.il experience in the area of Water /Wastewater, Oil & Gas, Energy and Environmental real-time monitoring and Oran Drach, control. Marketing Manager [email protected] Agrolan Moshav Nov Services Offered Ramat Hagolan 1292100 Israel +972-4-666-6999 Weather stations, storm water management, precision farming, measurement devices, sensors, diagnostic kits, www.agrolan.co.il remote telemetry by cellular, IoT - Internet of Things. -

Barriers to Peace in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies Founded by the Charles H. Revson Foundation Barriers to Peace in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Editor: Yaacov Bar-Siman-Tov 2010 Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies – Study no. 406 Barriers to Peace in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Editor: Yaacov Bar-Siman-Tov The statements made and the views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors. © Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Israel 6 Lloyd George St. Jerusalem 91082 http://www.kas.de/israel E-mail: [email protected] © 2010, The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies The Hay Elyachar House 20 Radak St., 92186 Jerusalem http://www.jiis.org E-mail: [email protected] This publication was made possible by funds granted by the Charles H. Revson Foundation. In memory of Professor Alexander L. George, scholar, mentor, friend, and gentleman The Authors Yehudith Auerbach is Head of the Division of Journalism and Communication Studies and teaches at the Department of Political Studies of Bar-Ilan University. Dr. Auerbach studies processes of reconciliation and forgiveness . in national conflicts generally and in the Israeli-Palestinian context specifically and has published many articles on this issue. Yaacov Bar-Siman-Tov is a Professor of International Relations at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and holds the Chair for the Study of Peace and Regional Cooperation. Since 2003 he is the Head of the Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies. He specializes in the fields of conflict management and resolution, peace processes and negotiations, stable peace, reconciliation, and the Arab-Israeli conflict in particular. He is the author and editor of 15 books and many articles in these fields. -

Municipal Amalgamation in Israel

TAUB CENTER for Social Policy Studies in Israel Municipal Amalgamation in Israel Lessons and Proposals for the Future Yaniv Reingewertz Policy Paper No. 2013.02 Jerusalem, July 2013 TAUB CENTER for Social Policy Studies in Israel The Taub Center was established in 1982 under the leadership and vision of Herbert M. Singer, Henry Taub, and the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. The Center is funded by a permanent endowment created by the Henry and Marilyn Taub Foundation, the Herbert M. and Nell Singer Foundation, Jane and John Colman, the Kolker-Saxon-Hallock Family Foundation, the Milton A. and Roslyn Z. Wolf Family Foundation, and the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. This volume, like all Center publications, represents the views of its authors only, and they alone are responsible for its contents. Nothing stated in this book creates an obligation on the part of the Center, its Board of Directors, its employees, other affiliated persons, or those who support its activities. Translation: Ruvik Danieli Editing and layout: Laura Brass Center address: 15 Ha’ari Street, Jerusalem Telephone: 02 5671818 Fax: 02 5671919 Email: [email protected] Website: www.taubcenter.org.il ◘ Internet edition Municipal Amalgamation in Israel Lessons and Proposals for the Future Yaniv Reingewertz Abstract This policy paper deals with municipal amalgamations in Israel, and puts forward a concrete proposal for merging 25 small municipalities with adjacent ones. According to an estimate based on the results of the municipal amalgamations reform carried out in Israel in 2003 (Reingewertz, 2012), thanks to the economies of scale in providing public services, these unifications are expected to generate savings of approximately NIS 131 million per annum. -

United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: 5,412,903 Zemach Et Al

O US005412903A United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: 5,412,903 Zemach et al. (45) Date of Patent: May 9, 1995 54). SEA CAGE FISH FARMING SYSTEM 4,244,323 1/1981 Morimura ............................. 43/102 75) Inventors: Shalom Zemach, Kfar Yona; Yitzhak Primary Examiner-Kurt Rowan Farin, Ganei Tikva, both of Israel Attorney, Agent, or Firm-Mark M. Friedman 73) Assignee: Metal Yglem Vashkoht Ltd., Tel 57 ABSTRACT V1V, Israe A fish cage system, which includes a fish cage having (21) Appl. No.: 197993 one or more cables connected to it. The fish cage and 22 Filed: Feb. 17, 1994 cable(s) have a combined buoyancy which is such that 6 at least a portion of the fish cage is normally located at s 8 o was a a a - - - - - - - as a a a AOK34: or above the water surface. The cable(s) are connected 58) FiField fa off Searchsearch ......................- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 43/103,103s s 43. 76 4 s combinedto a sinker buoyancy whose weight of the isfish sufficient cage cable(s). to overcome The sinker the is also connected to a second cable which is connected (56) References Cited to a buoy. The buoy contains a winch for alternately U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS shortening8 and lengtheningg g the effective length of the 1903,276 3/1933 Y 43/102 second cable so as to alternately allow said fish cage to 3,494,064s1 W/ 2/1970 Steina3a ....... ................................... ... float or to submerge. 4,092,797 6/1978 Azurin .................................. 43/102 4,147,130 4/1979 Goguel .................................. 43/102 11 Claims, 4 Drawing Sheets 4477 aaZZZZZZ U.S.