Open Thesis Final.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Filing Port Code Filing Port Name Manifest Number Filing Date Next

Filing Port Call Sign Next Foreign Trade Official Vessel Type Total Dock Code Filing Port Name Manifest Number Filing Date Next Domestic Port Vessel Name Next Foreign Port Name Number IMO Number Country Code Number Agent Name Vessel Flag Code Operator Name Crew Owner Name Draft Tonnage Dock Name InTrans 5204 WEST PALM BEACH, FL 5204-2021-00375 1/14/2021 - TROPIC MIST FREEPORT, GRAND BAHAMA I J8NZ 8204183 BS 3 400204 TROPICAL SHIPPING CO. VC 333 TROPICAL SHIPPING AND CONSTRUCTION COMPANY LTD. 14 TROPICAL SHIPPING AND CONSTRUCTION 15'0" 548 PORT OF PALM BEACH BERTHS NOS. 8 & 9 (2012) DLX 1803 JACKSONVILLE, FL 1803-2021-00350 1/14/2021 - SLNC MAGOTHY (EX. NORFLOK) GUANTANAMO BAY WDI3067 9418975 CU 3 1262669 CB AGENCIES US 310 ARGENT MARINE OPERATIONS, INC. 17 HS MAGOTHY LLC 27'0" 6089 BLOUNT ISLAND - BERTHS 4 - 6 LY 4601 NEW YORK/NEWARK AREA 4601-2021-01122 1/14/2021 BALTIMORE, MD MAERSK VILNIUS - 9V8503 9408956 - 6 395877 NORTON LILLY INTERNATIONAL SG 310 A.P. MOLLER MAERSK A/S 22 A.P. MOLLER SINGAPORE PTE, LTD 28'3" 8602 PORT NEWARK CONTAINER TERM (PNCT) BERTHS 53, 55, 57, 59 DFL 5301 HOUSTON, TX 5301-2021-01995 1/14/2021 - CHEMSTAR TIERRA ARATU 3EXM9 9827451 BR 2 49547-18 GENERAL STEAMSHIP INC. PA 112 IINO MARINE SERVICE CO., LTD. 24 SIETEMAR, S.A. 34'0" 6474 KINDER MORGAN GALENA PARK L 4601 NEW YORK/NEWARK AREA 4601-2021-01121 1/14/2021 NORFOLK, VA MELCHIOR SCHULTE - 9V3053 9676723 - 6 399740 Turkon America SG 310 BEACH ROAD PARK SHIPPING CO. -

NPDES WW Power Plant and Industrial with and Without Stormwater

COLOR KEY: Industry not covered by 40 CFR?? Does not appear to be but Double- Look Into. These may not be covered by 40 CFR. Check to be sure. Not appear to be Not sure. Not familiar enough with industry to Steam Electric Turbine. know if they have a Steam Electric Turbine. 40 CFR covers:(vii) Steam electric power generating facilities, including coal handling sites; Needs SW Permit? Is a Power plant, does not have a SW permit but DOES Needs SW Permit? Check to see if there are SW Not a Power Plant - have SW language in it. We need to outfalls. May need SW Permit. Ask the Region if Needs NPDES SW evaluate these. Ask the Region. they have been there… Permit? Look into. Has SW permit but may have coal pile on site - not covered in SW General Permit? Look at site and permit. Contact Region Has SW General or Individual Permit. No Action SW permit expired Has Ken Power plant? Permit Owner Facility County Region Class Expires SW permit SW text? Comments / Action Power Plant? Reviewed? SW language in permit NC0000396 NC0000396 Progress Energy Carolinas, Inc. Asheville Steam Electric Power Plant Buncombe Asheville Major 12/31/2010 none YES Power Plant - Needs NPDES SW Permit? Power plant yes Visual*, 2/yrVisual, 2/yr NC0003433 NC0003433 Progress Energy Carolinas, Inc. Cape Fear Steam Electric Power Plant Chatham Raleigh Major 7/31/2011 none YES Power Plant - Needs NPDES SW Permit? Power plant yes none NC0005363 NC0005363 Progress Energy Carolinas, Inc. Weatherspoon Steam Electric Plant Robeson Fayetteville Minor 7/31/2009 none YES Power Plant - Needs NPDES SW Permit? Power plant yes Visual, TSS, O&G, As, Cu, Fe, Hg, Se, pH: all 2/yrVisual, 2/yr NC0038377 NC0038377 Progress Energy Carolinas, Inc. -

Investment Performance Review for Period Ending March 31, 2018

PERIOD ENDING: MARCH 31, 2018 Investment Performance Review for Alameda County Employees’ Retirement Association 1st quarter summary THE ECONOMIC CLIMATE THE INVESTMENT CLIMATE Changing — The U.S. economy is expected to grow at around 2.2% in — Excitement and optimism over tax cuts helped lead market Q1. Economists expect a slightly quicker rate of growth equities higher to begin the year. However, markets dynamics throughout the year. We believe that this middle-of-the- stumbled in February – falling roughly 10%. Equities road expansion – characterized as not too fast and not too recovered much of the losses throughout the quarter, suggest a slow – may allow the U.S. economy to continue but then fell back to their lows at the end of March. neutral or mild expanding for longer than expected. risk overweight — 2018 is expected to be a banner year for U.S. corporate — The U.S. has enacted a 25% tariff on steel and a 10% tariff profits. Earnings for the calendar year are forecast to grow may be on aluminum, which went into effect on March 23rd. The 17.3%, with 7.3% revenue growth. These 2018 warranted U.S. also engaged with China over allegations of expectations may already be priced in. asymmetrical trade policies and intellectual property theft. — February’s market correction appeared isolated to the equity markets. “Risk-off” selling that often accompanies market drawdowns was not apparent – credit spreads, PORTFOLIO IMPACTS U.S. Treasuries, and gold, reacted minimally. — Global economic growth has improved – low inflation, strong employment, and accommodative foreign central ASSET ALLOCATION ISSUES bank policies have been supportive of equity prices. -

UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 13F Form 13F COVER PAGE Report for the Calendar Year or Quarter Ended: December 31, 2001 ------------------------------- Check here if Amendment [ ]; Amendment Number: ------------ This Amendment (Check only one.): [ ] is a restatement. [ ] adds new holdings entries. Institutional Investment Manager Filing this Report: Name: The PNC Financial Services Group, Inc. ----------------------------------------------- Address: 249 Fifth Avenue ----------------------------------------- Pittsburgh, PA 15222-2707 ----------------------------------------- Form 13F File Number: 28-1235 -------------------- The institutional investment manager filing this report and the person by whom it is signed hereby represent that the person signing the report is authorized to submit it, that all information contained herein is true, correct and complete, and that it is understood that all required items, statements, schedules, lists, and tables, are considered integral parts of this form. Person Signing the Report on behalf of Reporting Manager: Name: Robert L. Haunschild ------------------------------------------------------- Title: Senior Vice President and Chief Financial Officer ----------------------------------------------------- Phone: (412) 762-5770 ------------------------------------------------------ Signature, Place, and Date of Signing: /s/ Robert L. Haunschild Pittsburgh, PA February 8, 2002 - -------------------------- --------------------- ----------------------- [Signature] -

The Rise of Latham & Watkins

The M&A journal - Volume 7, Number 5 The Rise of Latham & Watkins In 2006, Latham & Watkins came in fifth in terms of deal value.” the U.S. for deal value in Thompson Financial’s Mr. Nathan sees the U.S. market as crucial. league tables and took second place for the num- “This is a big part of our global position,” he says, ber of deals. “Seven years before that,” says the and it is the Achilles’ heel of some of the firm’s firm’s Charles Nathan, global co-chair of the main competitors. “The magic circle—as they firm’s Mergers and Acquisitions Group, “we dub themselves—Allen & Overy, Freshfields, weren’t even in the top twenty.” Latham also Linklaters, Clifford Chance and Slaughters— came in fourth place for worldwide announced have very high European M&A rankings and deals with $470.103 million worth of transactions, global rankings, but none has a meaningful M&A and sixth place for worldwide completed deals presence in the U.S.,” Mr. Nathan says. Slaughter Charles Nathan worth $364.051 million. & May, he notes, has no offices abroad. What is behind the rise of Latham & Watkins Similarly, in the U.S., Mr. Nathan says that his in the world of M&A? firm has a much larger footprint than its domestic “If you look back to the late nineties,” Mr. rivals. “Unlike all the other major M&A firms,” Nathan says, “Latham was not well-recognized he says, “we have true national representation. as an M&A firm. We had no persona in M&A. -

General* DC Private Equity Deals

WASHINGTON D.C. M&A ACTIVITY SNAPSHOTS 2002-2006 US M&A Global M&A Year Deal Count Volume (Millions) Year Deal Count Volume (Millions) 2006 11296 $ 1,776,292.75 2006 27912 $ 3,679,516.00 2005 10348 $ 1,297,140.12 2005 24526 $ 2,627,013.25 2004 9716 $ 971,593.81 2004 22102 $ 1,914,663.25 2003 8109 $ 627,724.56 2003 19353 $ 1,221,885.25 2002 7316 $ 528,825.06 2002 18557 $ 1,130,339.12 D.C. M&A - General* D.C. Private Equity Deals* Year Deal Count Volume (Millions) Year Deal Count Volume (Millions) 2006 174 $ 83,927.33 2006 74 $ 75,883.12 2005 184 $ 23,639.45 2005 32 $ 14,385.54 2004 121 $ 7,729.28 2004 16 $ 3,430.96 2003 85 $ 5,378.20 2003 8 $ 372.30 2002 59 $ 2,996.22 2002 2 $ 326.83 * Any involvement: includes deals with either target, acquirer * Any involvement: includes deals with either target, acquirer or or seller headquartered in the state. seller headquartered in the state. 2006 Active Industries - D.C. Industry Deal Count Volume (mil) Financial 11 $ 5,671.12 Consumer, Cyclica 10 $ 573.40 Consumer, Non-cy 10 $ 138.00 Industrial 2 $ 110.00 Communications 7 $ 8.00 * Target Only: Includes deals in which target is headquartered in the state Top 5 Deals 2006 - US * Any Involvement Announced Total Value Rank Date (mil.) Target Name Acquirer Name 1 3/ 5/06 $ 83,105.46 BELLSOUTH CORP AT&T INC 2 11/20/2006 $ 32,500.31 EQUITY OFFICE PROPERTIES TRUST BLACKSTONE GROUP 3 7/24/06 $ 32,193.46 HCA INC CONSORTIUM* 4 5/29/06 $ 27,449.73 KINDER MORGAN INC Knight Holdco LLC** 5 10/2/2006 $ 27,159.94 HARRAH'S ENTERTAINMENT INC CONSORTIUM*** * Bain Capital LLC, Kohlberg Kravis Robert, Merrill Lynch & Co Inc ** Goldman Sachs Group Inc, American International Group Inc, The Caryle Group, Riverstone Holdings LLC, Management Group *** Apollo Management LP, Texas Pacific Group 2006 TOP 5 DEALS - WASHINGTON D.C. -

SCHEDULE 14A Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(A) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 SCHEDULE 14A Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Filed by the Registrant x Filed by a Party other than the Registrant ¨ Check the appropriate box: ¨ Preliminary Proxy Statement ¨ Confidential, for use of the Commission only (as permitted by Rule 14a-6(e)(2)) x Definitive Proxy Statement ¨ Definitive Additional Materials ¨ Soliciting Material under Rule 14a-12 ManTech International Corporation (Name of Registrant as Specified In Its Charter) (Name of Person(s) Filing Proxy Statement, if other than the Registrant) Payment of Filing Fee (Check the appropriate box) x No fee required. ¨ Fee computed on table below per Exchange Act Rules 14a-6(i)(4) and 0-11. (1) Title of each class of securities to which transaction applies: (2) Aggregate number of securities to which transaction applies: (3) Per unit price or other underlying value of transaction computed pursuant to Exchange Act Rule 0-11 (Set forth the amount on which the filing fee is calculated and state how it was determined.): (4) Proposed maximum aggregate value of transaction: (5) Total fee paid: ¨ Fee paid previously with preliminary materials. ¨ Check box if any part of the fee is offset as provided by Exchange Act Rule 0-11(a)(2) and identify the filing for which the offsetting fee was paid previously. Identify the previous filing by registration statement number, or the Form or Schedule and the date of its filing. (1) Amount Previously Paid: (2) Form, Schedule or Registration Statement No.: (3) Filing Party: (4) Date Filed: 12015 Lee Jackson Highway Fairfax, VA 22033-3300 April 1, 2010 Dear Stockholder: You are cordially invited to attend the 2010 Annual Meeting of Stockholders of ManTech International Corporation, which will be held at The Hyatt Fair Lakes, 12777 Fair Lakes Circle, Fairfax, VA 22033, on Wednesday, May 12, 2010, at 11 am (EDT). -

Putnam Dynamic Asset Allocation Growth Fund the Fund's Portfolio 12/31/20 (Unaudited)

Putnam Dynamic Asset Allocation Growth Fund The fund's portfolio 12/31/20 (Unaudited) COMMON STOCKS (70.1%)(a) Shares Value Basic materials (3.0%) Akzo Nobel NV (Netherlands) 23,248 $2,497,284 Albemarle Corp. 29,230 4,312,010 Anglo American PLC (United Kingdom) 159,528 5,313,448 AptarGroup, Inc. 10,100 1,382,589 Ashland Global Holdings, Inc. 11,200 887,040 Asian Paints, Ltd. (India) 40,804 1,547,129 Axalta Coating Systems, Ltd.(NON) 45,800 1,307,590 BHP Billiton, Ltd. (Australia) 138,357 4,507,518 BHP Group PLC (United Kingdom) 50,941 1,342,490 Brenntag AG (Germany) 31,177 2,412,754 Celanese Corp. 7,400 961,556 Chemours Co. (The) 28,800 713,952 Compagnie De Saint-Gobain (France)(NON) 98,509 4,516,939 Covestro AG (Germany) 35,237 2,173,514 CRH PLC (Ireland) 189,981 8,030,907 Dow, Inc. 83,016 4,607,388 DuPont de Nemours, Inc. 40,327 2,867,653 Eastman Chemical Co. 24,400 2,446,832 Eiffage SA (France)(NON) 10,365 1,001,919 Fortescue Metals Group, Ltd. (Australia) 105,444 1,906,463 Fortune Brands Home & Security, Inc. 28,319 2,427,505 Freeport-McMoRan, Inc. (Indonesia) 269,290 7,006,926 ICL Group, Ltd. (Israel) 109,965 561,260 Koninklijke DSM NV (Netherlands) 15,524 2,674,257 LafargeHolcim, Ltd. (Switzerland) 33,896 1,860,118 LG Chemical, Ltd. (South Korea) 3,538 2,693,163 Linde PLC 6,200 1,610,164 NewMarket Corp. 1,200 477,948 Nitto Denko Corp. -

Investment Holdings As of June 30, 2019

Investment Holdings As of June 30, 2019 Montana Board of Investments | Portfolio as of June 30, 2019 Transparency of the Montana Investment Holdings The Montana Board of Investment’s holdings file is a comprehensive listing of all manager funds, separately managed and commingled, and aggregated security positions. Securities are organized across common categories: Pension Pool, Asset Class, Manager Fund, Aggregated Individual Holdings, and Non-Pension Pools. Market values shown are in U.S. dollars. The market values shown in this document are for the individual investment holdings only and do not include any information on accounts for receivables or payables. Aggregated Individual Holdings represent securities held at our custodian bank and individual commingled accounts. The Investment Holdings Report is unaudited and may be subject to change. The audited Unified Investment Program Financial Statements, prepared on a June 30th fiscal year-end basis, will be made available once the Legislative Audit Division issues the Audit Opinion. Once issued, the Legislative Audit Division will have the Audit Opinion available online at https://www.leg.mt.gov/publications/audit/agency-search-report and the complete audited financial statements will also be available on the Board’s website http://investmentmt.com/AnnualReportsAudits. Additional information can be found at www.investmentmt.com Montana Board of Investments | Portfolio as of June 30, 2019 2 Table of Contents Consolidated Asset Pension Pool (CAPP) 4 CAPP - Domestic Equities 5 CAPP - International -

Download Original Attachment

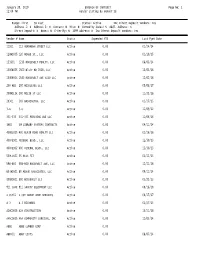

January 29, 2019 BOROUGH OF CARTERET Page No: 1 12:04 PM Vendor Listing By Vendor Id Range: First to Last Status: Active Inc Direct Deposit Vendors: Yes Address 1: N Address 2: N Contact: N Misc: N Commodity Codes: N Addl. Address: N Direct Deposit: N Notes: N E-Verify: N 1099 Address: N Inc Direct Deposit Vendors: Yes Vendor # Name Status Expended YTD Last Pymt Date 11201 112 HERMABNN STREET LLC Active 0.00 01/24/14 120MI005 120 MINUE ST., LLC Active 0.00 01/20/15 123501 1235 ROOSEVELT REALTY, LLC Active 0.00 06/05/14 1500B005 1500 Blair RD 2016, LLC Active 0.00 10/05/18 1540R00S 1540 ROOSEVELT AVE ASSO LLC Active 0.00 12/02/16 200 MID 200 MIDDLESEX LLC Active 0.00 05/08/17 200MILIK 200 MILIK ST LLC Active 0.00 11/22/16 28301 283 WASHINGTON, LLC Active 0.00 02/27/15 3-G 3-G Active 0.00 11/09/12 331-333 331-333 PERSHING AVE LLC Active 0.00 11/08/18 3M02 3M LIBRARY SYSTEMS CONTRACTS Active 0.00 04/11/14 400BL005 400 BLAIR ROAD REALTY LLC Active 0.00 02/26/16 400FED01 FEDERAL BLVD., LLC Active 0.00 12/30/13 400FED02 400 FEDERAL BLVD., LLC Active 0.00 12/30/13 55PLUS01 55 PLUS FIT Active 0.00 03/12/15 598-600 598-600 ROOSEVELT AVE, LLC Active 0.00 12/21/16 60 MIN01 60 MINUE ASSOCIATES, LLC Active 0.00 04/11/14 800ROO01 800 ROOSEVELT LLC Active 0.00 03/22/13 911 SAFE 911 SAFETY EQUIPMENT LLC Active 0.00 08/16/18 A CUT01 A CUT ABOVE HOME SERVICES Active 0.00 08/17/17 A J A J RICHARDS Active 0.00 02/27/13 A2HCO005 A2H CONSTRUCTION Active 0.00 10/21/16 AAACO005 AAA COMMUNITY SURGICAL, INC Active 0.00 12/05/14 ABBE ABBE LUMBER CORP Active 0.00 -

CAN FEP Companies 5004 3 M Company 5010 AAA 20609 Abbvie Corp 19500 Acadian Ambulance Service, Inc 17610 Accenture Ltd. 19619 Ac

CAN FEP Companies 5004 3 M Company 5010 AAA 20609 Abbvie Corp 19500 Acadian Ambulance Service, Inc 17610 Accenture Ltd. 19619 Acushnet Company 19724 Acushnet Company 17083 Advanced Mirco Device, Inc 20742 Aflac - Corp Only 15372 Alcon Laboratiories Inc 10362 Aldi Inc 18393 Allergan Inc 17645 Allianz Life Insurance Company 5094 Allstate Insurance Company 7650 Altadis USA Inc 5113 American Airlines 20340 American Association of Physicians 20116 American Axle & Manufacturing 5120 American Express Co 18777 American Tower 9491 Ametek 5162 Analog Devices 7372 AON Corp 6283 AP Moeller-Maersk Group 16851 Apple Inc 5177 Apria Healthcare 7313 Aramark Corporation 10662 Arbonne International 5184 Archer Daniels Midland Company 4006 ARI 7947 ARI 19909 Arizona Public Service (Aps) 5202 Astrazeneca 19127 At Properties 5207 AT&T Corp 20449 Auto Strap Transportation LLC 20502 Autodata Corporation 8478 Automatic Data Processing (ADP) 21944 Avera Health 20190 B P 20225 Babcock & Wilcox 7748 Bacardi USA, Inc 5253 Bank of America Corp 20495 Baptist Health South Florida 20495 Baptist Health South Florida 20940 Barkawi Management Consultants 5269 Bausch & Lomb 20582 BeautiControl 7383 Becton Dickinson and Companies 20749 BI Worldwide 19084 Biogen Idec 21232 Blackberry Corporation 20832 Bloomin Brand 5317 Blue Cross Blue Shield 8745 Blue Cross Blue Shield of Science 5336 Boston Science Corporation 13526 Braintree Labories, Inc 5349 Bristol-Myers Squibb 18867 Broadcom 5357 Brown-Forman 5384 Cablevision 10995 Caesars Entertainment Group 19659 Carefusion Corporation -

Student Managed Investment Fund Annual Report 2016 – 2017

Student Managed Investment Fund Annual Report 2016 – 2017 Table of Contents Letter from General Manager .........................................................................................................................................3 Mission Statement ...........................................................................................................................................................5 Overview and History .....................................................................................................................................................6 SMIF Advisory Board ....................................................................................................................................................8 SMIF Managers 2016-2017 ............................................................................................................................................9 Investment Policy Statement .........................................................................................................................................10 Economic Overview & Analysis ..................................................................................................................................12 U.S. GDP Growth ....................................................................................................................................................12 Employment .............................................................................................................................................................12