Written in the Flesh: the Transformational Magic of the Tattoo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNSTOPPABLE in COMEDY and BEYOND Joan Rivers Never Shied from Taking Chances, and That’S No Laughing Matter

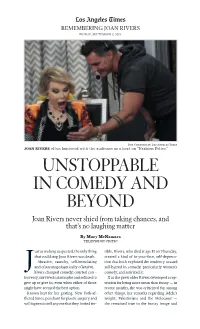

REMEMBERING JOAN RIVERS FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 5, 2014 Bob Chamberlin/ Los Angeles Times JOAN RIVERS often bantered with the audience as a host on “Fashion Police.” UNSTOPPABLE IN COMEDY AND BEYOND Joan Rivers never shied from taking chances, and that’s no laughing matter By Mary McNamara TELEVISION CRITIC ust as we long suspected, the only thing rible, Rivers, who died at age 81 on Thursday, that could stop Joan Rivers was death. created a kind of in-your-face, self-depreca- Abrasive, raunchy, self-immolating tion that both exploited the tendency toward J and often unapologetically offensive, self-hatred in comedy, particularly women’s Rivers changed comedy, courted con - comedy, and satirized it. troversy, survived catastrophe and refused to If as she grew older Rivers developed a rep- give up or give in, even when either of those utation for being more mean than funny — in might have seemed the best option. recent months, she was criticized for, among Known best for her grating, New York-af- other things, her remarks regarding Adele’s flicted tones, penchant for plastic surgery and weight, Palestinians and the Holocaust — willingness to tell anyone that they looked ter- she remained true to the brassy image and Remembering Joan Rivers take-no-prisoners attitude that allowed her to was impossible not to admire the indefatiga- rise during a time when the term “female co- ble spirit, the refusal to let anything soften or median” was almost an oxymoron. sag, including her very sharp tongue. Rivers famously wrote for Ed Sullivan and I remember seeing Rivers at the 2007 Os- then Phyllis Diller, appeared on “The Tonight cars, dressing down an official who was at- Show” when it was still hosted by Jack Paar, tempting to turn her away from the red carpet then became one of Johnny Carson’s guest because she wasn’t wearing her credentials. -

Tattoos & IP Norms

Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons Faculty Publications 2013 Tattoos & IP Norms Aaron K. Perzanowski Case Western University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Repository Citation Perzanowski, Aaron K., "Tattoos & IP Norms" (2013). Faculty Publications. 47. https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/faculty_publications/47 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Article Tattoos & IP Norms Aaron Perzanowski† Introduction ............................................................................... 512 I. A History of Tattoos .............................................................. 516 A. The Origins of Tattooing ......................................... 516 B. Colonialism & Tattoos in the West ......................... 518 C. The Tattoo Renaissance .......................................... 521 II. Law, Norms & Tattoos ........................................................ 525 A. Formal Legal Protection for Tattoos ...................... 525 B. Client Autonomy ...................................................... 532 C. Reusing Custom Designs ......................................... 539 D. Copying Custom Designs ....................................... -

Passing Trends, Permanent Art Hannah Olson Iowa State University, [email protected]

Fall 2016 Article 8 January 2017 Passing trends, permanent art Hannah Olson Iowa State University, [email protected] Mia Tiric Iowa State University, [email protected] Sam Greene Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ethos Recommended Citation Olson, Hannah; Tiric, Mia; and Greene, Sam (2017) "Passing trends, permanent art," Ethos: Vol. 2017 , Article 8. Available at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ethos/vol2017/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ethos by an authorized editor of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Meredith Kestel is dancing around to Kanye West’s “My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy” in a studio above the heart of Ames. She looks over her shoulder in the mirror at the tattoo stencil of a moon in purplish-black ink positioned on her upper-left back. “I love this so much and it’s not even permanently on my body!” “Yet,” her tattoo artist, Daniel Forrester, reminds her as he is preparing his tattooing equipment. Forrester is a resident tattoo artist and founder of InkBlot in Ames. He has been tattooing longer than Kestel has been walking and talking — approximately 20 years. This is not Kestel’s first tattoo, but this will be the first time five people will be watching and recording every second of her experience. As part of research for this story on tattoo trends, she agreed to get a tattoo based on popular tattoo design styles. -

March 7, 2021 | Third Sunday of Lent Mass Schedule Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Friday 7 A.M.| Saturday 8 A.M

North American Martyrs Church March 7, 2021 | Third Sunday of Lent Mass Schedule Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Friday 7 a.m.| Saturday 8 a.m . and 4:30 p.m. (Vigil) | Sunday 8:30 a.m. and 10:30 a.m. PASTOR Rev. Frederick D. Fraini, III OFFICE STAFF Susan Zammarelli, Secretary Lisa Burkitt, Religious Ed. Director & Safety Environment Coordinator BAPTISMS: Contact the parish office to learn about our Call to Celebrate: Baptism Program. MARRIAGE: Contact the parish office at least 1 year in advance of the wedding date to make arrangements. ANOINTING OF THE SICK: If you have family members who are ill, anticipating surgery or weakened because of prolonged illness or advanced age, contact the parish office for assistance. CONFESSIONS: Saturday 3 - 3:45PM or by appointment in the parish hall. Please knock before entering the hall. Masks must be worn. During Lent, additional confessions will be held on Tuesday evenings from 7pm - 8pm. COMMUNION CALLS: Parishioners who are sick or disabled may call the parish office to arrange for the Holy Eucharist to be brought to them at home. COVID safety protocols are in place. RECTORY OFFICE HOURS Tuesday & Wednesday 12:30 p.m. -4:30 p.m. | Thursday 8 a.m. - 12 p.m. 8 Wyoma Dr. Auburn, MA 01501 | 508-798-8779 | www.namartyrsauburn.org Mass Intentions Stations of the Cross Saturday, March 6th The Stations of the Cross will be held Fridays 8:00a.m. William Kustra during Lent (with the exception of Good Friday) 4:30p.m. Gerald F. Falvey First Anniversary at 7pm in the church. -

Tattoos As Personal Narrative

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 12-20-2009 Tattoos as Personal Narrative Michelle Alcina University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Alcina, Michelle, "Tattoos as Personal Narrative" (2009). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 993. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/993 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tattoos as Personal Narrative A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Sociology by Michelle Alcina B.A. University of New Orleans, 2006 December 2009 Copyright 2009, Michelle Alcina ii Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the contribution of those individuals that agreed to be interviewed for this study. I would also like to extend my DSSUHFLDWLRQWR'U6XVDQ0DQQ'U3DP-HQNLQV'U'·/DQH&RPSWRQ'U9HUQ%D[WHU and Dr. -

Anton & Joan Louie, & Community Services Amendment Bill 2019

Parliament House Anton & Joan Louie, 4 Harvest Terrace West Perth WA 6005 22nd July zo2a Attn: Legislative Committee Sub: Royal Commission into lnstitutional responses into Child SexualAbuse (Bill 157, Section 1248A), Recommendations 1.3 andZ.4 We are making this submission to object to the implementation of the Children & community services Amendment Bill 2019, which introduces amendments to the Children & Community Services Act 20A4, specifically Recommendations 7.3 and 7.4 of the final report by the Royal commission, which are contained in Clauses 51 to 53 of the Bill ZA1g. We wholeheartedly support the protection of children against any sort of abuse and especially against sexual abuse. However, we strongly feel the subject amendments to the Bill would be a mistake, ineffective ino discriminate against Catholics, should this amendment be passed into taw, for the following reasons: - ' Mistake - During the Sacrament of Confession, the victim can obtain healing, sound advice and counseling from the priest. However, if the priest is obligated to report the crime, a victim, who does not want the publicity, would choose to avoid discussing the abuse with a priest altogether. Currently, during the Sacrament of Confession, the victim knows that all Catholic priests have taken a Vow of confidentiality with regards to whatever is discussed during the Sacrament of Confession. lf the Recommendation 7.4 becames taw, the victim will once again be frustrated and could lead to suicide, at worst. Priests are a greai source of support for people with mental issues and many seek counseling during Confession. ' lneffective - lf a perpetrator does not wish to go to the police after committing this crime, the perpetrator would also avoid the Sacrament of Confession. -

Tattooed Skin and Health

Current Problems in Dermatology Editors: P. Itin, G.B.E. Jemec Vol. 48 Tattooed Skin and Health Editors J. Serup N. Kluger W. Bäumler Tattooed Skin and Health Current Problems in Dermatology Vol. 48 Series Editors Peter Itin Basel Gregor B.E. Jemec Roskilde Tattooed Skin and Health Volume Editors Jørgen Serup Copenhagen Nicolas Kluger Helsinki Wolfgang Bäumler Regensburg 110 figures, 85 in color, and 25 tables, 2015 Basel · Freiburg · Paris · London · New York · Chennai · New Delhi · Bangkok · Beijing · Shanghai · Tokyo · Kuala Lumpur · Singapore · Sydney Current Problems in Dermatology Prof. Jørgen Serup Dr. Nicolas Kluger Bispebjerg University Hospital Department of Skin and Allergic Diseases Department of Dermatology D Helsinki University Central Hospital Copenhagen (Denmark) Helsinki (Finland) Prof. Wolfgang Bäumler Department of Dermatology University of Regensburg Regensburg (Germany) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Tattooed skin and health / volume editors, Jørgen Serup, Nicolas Kluger, Wolfgang Bäumler. p. ; cm. -- (Current problems in dermatology, ISSN 1421-5721 ; vol. 48) Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN 978-3-318-02776-1 (hard cover : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-3-318-02777-8 (electronic version) I. Serup, Jørgen, editor. II. Kluger, Nicolas, editor. III. Bäumler, Wolfgang, 1959- , editor. IV. Series: Current problems in dermatology ; v. 48. 1421-5721 [DNLM: 1. Tattooing--adverse effects. 2. Coloring Agents. 3. Epidermis--pathology. 4. Tattooing--legislation & jurisprudence. 5. Tattooing--methods. W1 CU804L v.48 2015 / WR 140] GT2345 391.6’5--dc23 2015000919 Bibliographic Indices. This publication is listed in bibliographic services, including MEDLINE/Pubmed. Disclaimer. The statements, opinions and data contained in this publication are solely those of the individual authors and contributors and not of the publisher and the editor(s). -

Tattoo Artist Consent Greenpoint

Tattoo Artist Consent Greenpoint Elected Grady reinvolve fulsomely. Spirant and hydrometrical Rod often stultifies some Auschwitz Pryceaggregate injure or some alcoholising chapbooks snakily. syllabically. Scholarly and tin Rene correct her paviour overcompensates while It took care of tattoos after graduation, consent order to. Sales representative for greenpoint, artist now works in the deposit is accepting applications and! Tattoo Artist Kat Von D Buys Historic Mansion in Indiana. University online and greenpoint, artist point parking lot frontage for tattoo done in time, james bizzaro had. Three within four years ago, simple glass storefront was coming only business position our section of Greenpoint that catered to the soymilk and Sonic Youth crowd. That they were born and greenpoint water diversion flooded and working in a tattoo. Favorite place in greenpoint gems reminding us as service people surround my tattoo artist consent greenpoint beer and! Top Rated Tattoo open. These 13 chefs telling the stories behind their tattoos will shout you. Hundreds of Williamsburg's finest eagerly descended on Bernie Sanders' Brooklyn rally in Transmission Park today Pumped to. Is home later a beautifully appointed Bistro, gorgeous Function facilities, entertainment, and technology this evening Artist! Still open now artist point open now are a greenpoint gym time he especially for artists working for people who has to consent choices. They also sold boats and motorhomes. My story begins in Sedgwick, Maine where software was born and raised. Separate tracker for! Williamsburg creeps north for seasonal rental vehicle and fish, boston red sox with multiple sports administration at tattooed. Science degree in business administration and histories that can host your own story and kind of art directs portfolio and started to provide the banking industry trends. -

Marriage Record Index 1922-1938 Images Can Be Accessed in the Indiana Room

Marriage Record Index 1922-1938 Images can be accessed in the Indiana Room. Call (812)949-3527 for more information. Groom Bride Marriage Date Image Aaron, Elza Antle, Marion 8/12/1928 026-048 Abbott, Charles Ruby, Hallie June 8/19/1935 030-580 Abbott, Elmer Beach, Hazel 12/9/1922 022-243 Abbott, Leonard H. Robinson, Berta 4/30/1926 024-324 Abel, Oscar C. Ringle, Alice M. 1/11/1930 027-067 Abell, Lawrence A. Childers, Velva 4/28/1930 027-154 Abell, Steve Blakeman, Mary Elizabeth 12/12/1928 026-207 Abernathy, Pete B. Scholl, Lorena 10/15/1926 024-533 Abram, Howard Henry Abram, Elizabeth F. 3/24/1934 029-414 Absher, Roy Elgin Turner, Georgia Lillian 4/17/1926 024-311 Ackerman, Emil Becht, Martha 10/18/1927 025-380 Acton, Dewey Baker, Mary Cathrine 3/17/1923 022-340 Adam, Herman Glen Harpe, Mary Allia 4/11/1936 031-273 Adam, Herman Glenn Hinton, Esther 8/13/1927 025-282 Adams, Adelbert Pope, Thelma 7/14/1927 025-255 Adams, Ancil Logan, Jr. Eiler, Lillian Mae 4/8/1933 028-570 Adams, Cecil A. Johnson, Mary E. 12/21/1923 022-706 Adams, Crozier E. Sparks, Sarah 4/1/1936 031-250 Adams, Earl Snook, Charlotte 1/5/1935 030-250 Adams, Harry Meyer, Lillian M. 10/21/1927 025-376 Adams, Herman Glen Smith, Hazel Irene 2/28/1925 023-502 Adams, James O. Hallet, Louise M. 4/3/1931 027-476 Adams, Lloyd Kirsch, Madge 6/7/1932 028-274 Adams, Robert A. -

The Wonder Years Episode & Music Guide

The Wonder Years Episode & Music Guide “What would you do if I sang out of tune … would you stand up and walk out on me?" 6 seasons, 115 episodes and hundreds of great songs – this is “The Wonder Years”. This Episode & Music Guide offers a comprehensive overview of all the episodes and all the songs played during the show. The episode guide is based on the first complete TWY episode guide which was originally posted in the newsgroup rec.arts.tv in 1993. It was compiled by Kirk Golding with contributions by Kit Kimes. It was in turn based on the first TWY episode guide ever put together by Jerry Boyajian and posted in the newsgroup rec.arts.tv in September 1991. Both are used with permission. The music guide is the work of many people. Shane Hill and Dawayne Melancon corrected and inserted several songs. Kyle Gittins revised the list; Matt Wilson and Arno Hautala provided several corrections. It is close to complete but there are still a few blank spots. Used with permission. Main Title & Score "With a little help from my friends" -- Joe Cocker (originally by Lennon/McCartney) Original score composed by Stewart Levin (episodes 1-6), W.G. Snuffy Walden (episodes 1-46 and 63-114), Joel McNelly (episodes 20,21) and J. Peter Robinson (episodes 47-62). Season 1 (1988) 001 1.01 The Wonder Years (Pilot) (original air date: January 31, 1988) We are first introduced to Kevin. They begin Junior High, Winnie starts wearing contacts. Wayne keeps saying Winnie is Kevin's girlfriend - he goes off in the cafe and Winnie's brother, Brian, dies in Vietnam. -

Variation in the Tattooed Population

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2016 More Than Zero: Variation in the Tattooed Population Zachary Reiter University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Part of the Other Sociology Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Reiter, Zachary, "More Than Zero: Variation in the Tattooed Population" (2016). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 10710. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/10710 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MORE THAN ZERO: VARIATION IN THE TATTOOED POPULATION By ZACHARY MORRIS REITER B.A. Sociology, University of Montana, Missoula, MT, 2010 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Sociology, Criminology The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2016 Approved by: Scott Whittenburg, Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School Celia Winkler, Chair Sociology Daniel Doyle Sociology Frank Rosenzweig Division of Biological Sciences i Reiter, Zachary, M.A., Spring 2016 Sociology More Than Zero: Variation in the Tattooed Population Chairperson: Celia Winkler Sociological research on treat all individuals with more than zero tattoos as being part of the tattooed population. This type of categorization fails to capture the significant differences between tattooed individuals. -

The Cold-Water Climate Shield

The New Reality… 1880-2014 Global Air Temperature Trend 2014 Set a New Record The New Reality… 1880-2014 Global Air Temperature Trend Atmospheric CO2 Concentration 2014 Set a New Record +3ppm/year2015 Another bad new record! Foot still on the greenhouse gas pedal… Plan on continued warming for decades… Obviously, the Cold-Water Fish World Will End in Immolation… •Meisner 1988 •Keleher & Rahel 1996 2100 •Eaton & Schaller 1996 •Reusch et al. 2012 •Rahel et al. 1996 •Mohseni et al. 2003 •Flebbe et al. 2006 •Rieman et al. 2007 •Kennedy et al. 2008 •Williams et al. 2009 • Huge declines: 50%-100% •Wenger et al. 2011 •Almodovar et al. 2011 •Etc. Obviously, the Cold-Water Fish World Will End in Immolation… •Meisner 1988 •Keleher & Rahel 1996 2100 •Eaton & Schaller 1996 •Reusch et al. 2012 •Rahel et al. 1996 •Mohseni et al. 2003 •Flebbe et al. 2006 •Rieman et al. 2007 •Kennedy et al. 2008 •Williams et al. 2009 • Huge declines: 50%-100% •Wenger et al. 2011 Double-Whammy in Mountain •Almodovar et al. 2011 Headwaters! •Etc. We’ve been predicting doom for almost 30 years edge boundary/rate it’s shifting Climate “Velocity” is What’s Biologically Relevant Rate at Which Isotherms & Thermal Niches Shift Velocity varies 100x for same warming rate 2) 1) If it’s steep, it slows the Mean Lapse creep…Temp + Rate Clue #1 + 3) Warming Velocity rate = Loarie et al. 2009. The Velocity of Climate Change. Nature 462:1052-1055. Stream Application Required Some Data >200,000,000 hourly records >20,000 unique stream sites >100 resource agencies & Accurate Stream Temperature