2 Improving Tourism in Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I. Organizational Chart

I. Organizational Chart SBP BANKING SERVICES CORPORATION Board of Directors Managing Director Aftab Mustafa Khan MD Secretariat Head Office Field Offices Personnel Management Currency Management Department Karachi Office Lahore Office Department Javaid Iqbal Taslim Kazi Dr.Muhammad Saleem Amjad Manzoor Chief Manager Chief Manager Director Director Islamabad Office Peshawar Office Foreign Exchange Operations Development Finance Support Tariq Riaz Muhammad Tanwirul Islam Department Department Chief Manager Chief Manager Syed Shahzad Safdar Zaidi Muhammad Mazharul Haq Director Director Rawalpindi Office Quetta Office Asad Shah Ali Hussain Chief Manager Chief Manager * Training & Development Department Accounts Department Amjad Manzoor Muhammad Habib Khan Director* Director Hyderabad Office Faisalabad Office Ali Hussain Sajjad Ali Shah Chief Manager Chief Manager General Services Department Internal Audit Department Zafar Iqbal Maraj Mahmood Director Head Multan Office North Nazimabad Office Javaid Iqbal Marath Ansar Iftikhar Butt Chief Manager Chief Manager Quality Assurance Department Engineering Department Feroza Nabeel Qureshi Fazli Hameed Director Head Muzaffarabad Office Sukkur Office Muhammad Tahir Malik Muhammad Ashraf Khokhar Chief Manager (A) Chief Manager Foreign Exchange Adjudication Department Internal Bank Security Muhammed Saleem Rehmani Department Brig.(R) M. Pervez Akbar Bahawalpur Office Gujranwala Office Director Khadim Hussain Aamir Nazir Bhatti Director Chief Manager (A) Chief Manager (A) * Additional Charge Sialkot Office D.I. Khan Office ( A) Acting Basis Azhar Iqbal Muhammad Humayun Khan Chief Manager Chief Manager Annual Performance Review of SBP BSC FY12 II. Board of Directors S # Name Status 1 Mr. Yaseen Anwar Governor SBP/ Chairman of SBP BSC Board 2 Mr. Abdul Wajid Rana Member/ Principal Officer, Finance Division, GoP 3 Mr. Mirza Qamar Beg Member 4 Mr. -

Problems Caused by Tourism in Kaghan Valley, Pakistan: a Study Based - on Local Community Perception

Global Social Sciences Review (GSSR) Vol. IV, No. III (Summer 2019) | Page: 284 – 291 7 III).3 Problems Caused by Tourism in Kaghan Valley, Pakistan: A Study Based - on Local Community Perception PhD Scholar, Department of Archaeology, Hazara University Anas Mahmud Arif Mansehra, Kp, Pakistan. Email: [email protected] Associate Professor, Department of Archaeology, Hazara University Shakir Ullah Mansehra, Kp, Pakistan. Director, Directorate of Archaeology and Museums, Government of Abdul Samad Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Tourism being one of the greatest and fastest growing industries of the world is contributing Abstract significantly to the development of countries and the host communities. But this industry is facing many problems in most of the developing countries including Pakistan. Most of the issues are raised due to http://dx.doi.org/10.31703/gssr.2019(IV lack of planning which not only dissatisfies the tourists but also has negative impacts on the local communities. Unplanned tourism not only affects the host guest relationship but also the tourism resources of an area. The study in hand is author’s part of PhD URL: Key Words research and highlights the problems of host regions caused by tourism in | | Pakistan, taking Kaghan valley as case study. The results of the study show Tourism, Kaghan Valley, 7 that if proper measures are not taken well in time, the unplanned tourism Problems, Tourists, Local will destroy the natural and socio-cultural environment of the valley very III).3 - Community, Tourism soon. Resources, Socio Cultural Environments 10.31703/gssr.2019(IV Introduction Pakistan is bestowed with a lot of natural and cultural resources which can be utilized for tourism. -

Sindh Coast: a Marvel of Nature

Disclaimer: This ‘Sindh Coast: A marvel of nature – An Ecotourism Guidebook’ was made possible with support from the American people delivered through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of IUCN Pakistan and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of USAID or the U.S. Government. Published by IUCN Pakistan Copyright © 2017 International Union for Conservation of Nature. Citation is encouraged. Reproduction and/or translation of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from IUCN Pakistan, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from IUCN Pakistan. Author Nadir Ali Shah Co-Author and Technical Review Naveed Ali Soomro Review and Editing Ruxshin Dinshaw, IUCN Pakistan Danish Rashdi, IUCN Pakistan Photographs IUCN, Zahoor Salmi Naveed Ali Soomro, IUCN Pakistan Designe Azhar Saeed, IUCN Pakistan Printed VM Printer (Pvt.) Ltd. Table of Contents Chapter-1: Overview of Ecotourism and Chapter-4: Ecotourism at Cape Monze ....... 18 Sindh Coast .................................................... 02 4.1 Overview of Cape Monze ........................ 18 1.1 Understanding ecotourism...................... 02 4.2 Accessibility and key ecotourism 1.2 Key principles of ecotourism................... 03 destinations ............................................. 18 1.3 Main concepts in ecotourism ................. -

Chapter 5.2: Tourism Development

PUNJAB ECONOMIC | REPORT national GDP in 2015. If we include indirect and induced eects of tourism, the contribution of the sector increases to Tourism Development PKR 1,918.5 bn or almost 7 percent of GDP. Domestic tourism in a country tends to precede international tourism. More than 45 million domestic tourists travel 5.2.0 Introduction each year across Pakistan.2 As per World Travel and Tourism Council estimates, in the year 2015, domestic travel spend- ing in Pakistan claimed 90.8 percent of direct travel and tourism GDP. Domestic travel spending is expected to grow by Pakistan is endowed with immense geographical beauty with an equally rich and diverse tapestry of cultural heritage in 3 percent in 2016 to more than PKR 1 trillion and rise by 5.3 percent per annum to almost two trillion rupees in 2026. every province. Notwithstanding that, for a host of factors, the performance and state of tourism in the country is much lower than its potential, especially if compared to similar countries. Direct contribution of tourism towards Pakistan’s e gures below show Pakistan’s relative positioning in tourism export. Both gures clearly indicate that Pakistan is not GDP was PKR 793.0 bn in 2016, this is equivalent to 2.7% of GDP, which is a mere fraction of the sector’s potential.1 competitive as spending by foreigners is less than the comparator group countries shown. Pakistan’s international tourist Now that tourism is a provincial subject, there exists a great opportunity for Punjab to formulate an eective and ecient receipts (excluding travel) as percentage of GDP are the lowest when compared to the world average, India and South institutional framework to unravel the tourism potential of the province to the fullest. -

THE POLITICS of TOURISM in ASIA the POLITICS of TOURISM in ASIA Linda K

THE POLITICS OF TOURISM IN ASIA THE POLITICS OF TOURISM IN ASIA Linda K. Richter 2018 Open Access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 In- ternational (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non-commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require per- mission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Cre- ative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824880163 (PDF) 9780824880170 (EPUB) This version created: 17 May, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. © 1989 University of Hawaii Press All rights reserved Contents Acknowledgments vi Abbreviations Used in Text viii 1. The Politics of Tourism: An Overview 1 2. About Face: The Political Evolution of Chinese Tourism Policy 25 3. The Philippines: The Politicization of Tourism 57 4. Thailand: Where Tourism and Politics Make Strange Bedfellows 92 5. Indian Tourism: Pluralist Policies in a Federal System 115 6. Creating Tourist “Meccas” in Praetorian States: Case Studies of Pakistan and Bangladesh 153 Pakistan 153 Bangladesh 171 7. Sri Lanka and the Maldives: Islands in Transition 178 Sri Lanka 178 The Maldives 186 8. Nepal and Bhutan: Two Approaches to Shangri-La 190 Nepal 190 Bhutan 199 9. -

Why Invest in Tourism in Pakistan? Examining Evidence from Keenjhar Lake

Policy Brief Number 53-11, June 2011 Why invest in Tourism in Pakistan? Examining Evidence from Keenjhar Lake Regional and sectoral development within a country is never straight In the fiscal year 2004-2005 the STDC forward and offers many challenges. In this policy brief, we examine the received PKR 2.5 million (USD 30,599) recreational use of Pakistan’s largest freshwater lake and ask whether worth of grant-in-aid financial support. further investment in tourism development is warranted. The study is However, it also recently requested the work of Ali Dehlavi and Iftikhar Hussain Adil from the Indus for All approximately the same amount as Programme of the World Wide Fund for Nature, Pakistan. a one-time grant to help overcome a “financial crisis”. As a public limited Keenjhar lake is a large fresh water lake in Sindh Province that supplies fish, company, the corporation has to recreational services and drinking water to Karachi. One issue in developing the justify the money it receives from the region around the lake is whether there is a significant amount of tourism flow to the government. The STDC is therefore area. This study estimates that, on average, approximately 1,000 visitors come to interested in understanding the the lake every day for recreation. The value visitors place on recreation at Keenjhar economic value of the recreational lake is around PKR 3.5 billion (or USD 42 million1). In contrast, current revenues services it manages. This study attempts to the government from entrance and parking fee collections amount to about 0.2% to provide this information. -

Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber- Pakhtunkhwa

Working paper Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber- Pakhtunkhwa A Medium Term Strategy for Inclusive Growth Full Report April 2015 When citing this paper, please use the title and the following reference number: F-37109-PAK-1 Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa A Medium Term Strategy for Inclusive Growth International Growth Centre, Pakistan Program The International Growth Centre (IGC) aims to promote sustainable growth in developing countries by providing demand-led policy advice informed by frontier research. Based at the London School of Economics and in partnership with Oxford University, the IGC is initiated and funded by DFID. The IGC has 15 country programs. This report has been prepared under the overall supervision of the management team of the IGC Pakistan program: Ijaz Nabi (Country Director), Naved Hamid (Resident Director) and Ali Cheema (Lead Academic). The coordinators for the report were Yasir Khan (IGC Country Economist) and Bilal Siddiqi (Stanford). Shaheen Malik estimated the provincial accounts, Sarah Khan (Columbia) edited the report and Khalid Ikram peer reviewed it. The authors include Anjum Nasim (IDEAS, Revenue Mobilization), Osama Siddique (LUMS, Rule of Law), Turab Hussain and Usman Khan (LUMS, Transport, Industry, Construction and Regional Trade), Sarah Saeed (PSDF, Skills Development), Munir Ahmed (Energy and Mining), Arif Nadeem (PAC, Agriculture and Livestock), Ahsan Rana (LUMS, Agriculture and Livestock), Yasir Khan and Hina Shaikh (IGC, Education and Health), Rashid Amjad (Lahore School of Economics, Remittances), GM Arif (PIDE, Remittances), Najm-ul-Sahr Ata-ullah and Ibrahim Murtaza (R. Ali Development Consultants, Urbanization). For further information please contact [email protected] , [email protected] , [email protected] . -

Pdf | 564.01 Kb

Food Commodities Photo WFP/Aman ur Rehman khan Weekly Market Monitor Report WFP VAM | Food Security Analysis Pakistan | 13 October 2020 HIGHLIGHTS • Weekly average retail prices update as of 8th of October 2020 indicates overall the prices of staple cereals and non-cereals foods experienced negligible to slight fluctuations, except for eggs which experienced a significant increase, when compared to the previous week’s prices; • Cereals: (wheat, wheat flour, rice Irri-6 and rice Basmati). Overall, the average retail prices for wheat and wheat flour slightly increased along with negligible increases in the prices of rice Irri-6 and rice Basmati from the previous week; • Non-cereals: overall, compared to the previous week, the average retail prices of essential non-cereals registered a significant increase for eggs along with a slight increase for live chicken and negligible increases for sugar, cooking oil, pulses gram and Masoor. Whereas, negligible decreases were noted in the prices of pulses Mash and Moong while the price of vegetable ghee remained unchanged from the previous week; • The average ToT slightly decreased by 4% from the previous week. Market Monitor | Pakistan | 13 October 2020 Page 2 To monitor the impact of COVID-19 on market prices, the average retail prices1 of cereals and non-cereals essential food commodities across the country’s main markets2 in or near COVID-19 hotspots cities (Swat, Peshawar, Islamabad, Rawalpindi, Sialkot, Gujranwala, Faisalabad, Gujrat, Lahore, Multan, Ghotki, Sukkur, Hyderabad, Karachi and Quetta)3 -

TCS Offices List.Xlsx

S No Cities TCS Offices Address Contact 1 Hyderabad TCS Office Agriculture Shop # 12 Agricultural Complex Hyderabad 0316-9992350 2 Hyderabad TCS Office Rabia Square SHOP NO:7 RABIA SQUARE HYDER CHOCK HYDERABAD SINDH PAKISTAN 0316-9992351 3 Hyderabad TCS Office Al Noor Citizen Colony SHOP NO: 02 AL NOOR HEIGHTS JAMSHORO ROAD HYDERABAD SINDH 0316-9992352 4 Hyderabad TCS Office Qasimabad Opposite Larkana Bakkery RIAZ LUXURIES NEAR CALTEX PETROL PUMP MAIN QASIMABAD ROAD HYDERABAD SINDH 0316-9992353 5 Hyderabad TCS Office Market Tower Near Liberty Plaza SHOP NO: 26 JACOB ROAD TILAK INCLINE HYDERABAD SINDH 0316-9992354 6 Hyderabad TCS Office Latifabad No 07 SHOP NO" 01 BISMILLAH MANZIL UNIT NO" 07 LATIFABAD HYDERABAD SINDH 0316-9992355 7 Hyderabad TCS Office Auto Bhan Opposite Woman Police Station Autobhan Road near women police station hyderabad 0316-9992356 8 Hyderabad TCS Office SITE Area Area Office Hyderabad SITE Autobhan road near toyota motors site area hyderabad 0316-9992357 9 Hyderabad TCS Office Fatima Height Saddar Shop No.12 Fatima Heights Saddar Hyderabad 0316-9992359 10 Hyderabad TCS Office Sanghar SHOP NO: 02 BAIT UL FAZAL BUILDING M A JINNAH ROAD SANGHAR 0316-9992370 11 Hyderabad TCS Office Tando allah yar SHOP NO: 02 MAIN BUS STOP NEAR NATIONA BANK TDA 0316-9992372 12 Hyderabad TCS Office Nawabshah Near PTCL SUMERA PALACE HOSPITAL ROAD NAAWABSHAH 0316-9992373 13 Hyderabad TCS Office Tando Muhammad Khan AL FATEH CHOCK ADJUCENT HABIB BANK STATION ROAD TANDO MOHD KHAN 0316-9992374 14 Hyderabad TCS Office Umer Kot JAKHRA MARKET -

Invitation for Bids

INVITATION FOR BIDS 1. National Highway Authority (NHA) Re-invites sealed bids from eligible construction firms registered with income tax department having valid PEC registration & specialization for the following works Sr PEC Category & Contract# Work Description / Route # Specialization Construction of 08 Lanes Toll Plaza KM: 370- C-4 with Specialization 01 TP-2018-19-SN-01 371(N-5) Kandyaro in CE-01 & CE-10 Construction of 08 Lanes Toll Plaza KM: 534- C-4 with Specialization 02 TP-2018-19-SN-02 535(N-5) Ghotki in CE-01 & CE-10 Construction of 06 Lanes Toll Plaza KM: 483- C-5 with Specialization 03 TP-2018-19-SN-03 484(N-55) Kashmore in CE-01 & CE-10 Construction of 06 Lanes Toll Plaza KM: 09- C-4 with Specialization 04 TP-2018-19-SN-04 10(LKBP) Larkana in CE-01 & CE-10 Construction of 06 Lanes Toll Plaza KM: 33- C-4 with Specialization 05 TP-2018-19-SN-05 34(M-8) Ratodero in CE-01 & CE-10 2. Complete set of bidding documents (for above mentioned Works), containing detailed terms and conditions, method of procurement (Single Stage – Two Envelope procedure) for submission of bids, bid security, bid validity, opening of bid, evaluation criteria, clarification/rejection of bids, performance guarantee etc. are available on NHA website for downloading free of cost. Bidders are also advised to follow the NHA website for updates of bidding schedule and addendum(s), if any 3. The bids prepared in accordance with the instructions contained in the bidding documents must reach at the address mentioned below on or before 16th July, 2021 until 1100 Hours. -

Part-I: Post Code Directory of Delivery Post Offices

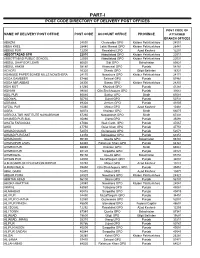

PART-I POST CODE DIRECTORY OF DELIVERY POST OFFICES POST CODE OF NAME OF DELIVERY POST OFFICE POST CODE ACCOUNT OFFICE PROVINCE ATTACHED BRANCH OFFICES ABAZAI 24550 Charsadda GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24551 ABBA KHEL 28440 Lakki Marwat GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28441 ABBAS PUR 12200 Rawalakot GPO Azad Kashmir 12201 ABBOTTABAD GPO 22010 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22011 ABBOTTABAD PUBLIC SCHOOL 22030 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22031 ABDUL GHAFOOR LEHRI 80820 Sibi GPO Balochistan 80821 ABDUL HAKIM 58180 Khanewal GPO Punjab 58181 ACHORI 16320 Skardu GPO Gilgit Baltistan 16321 ADAMJEE PAPER BOARD MILLS NOWSHERA 24170 Nowshera GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24171 ADDA GAMBEER 57460 Sahiwal GPO Punjab 57461 ADDA MIR ABBAS 28300 Bannu GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28301 ADHI KOT 41260 Khushab GPO Punjab 41261 ADHIAN 39060 Qila Sheikhupura GPO Punjab 39061 ADIL PUR 65080 Sukkur GPO Sindh 65081 ADOWAL 50730 Gujrat GPO Punjab 50731 ADRANA 49304 Jhelum GPO Punjab 49305 AFZAL PUR 10360 Mirpur GPO Azad Kashmir 10361 AGRA 66074 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66075 AGRICULTUR INSTITUTE NAWABSHAH 67230 Nawabshah GPO Sindh 67231 AHAMED PUR SIAL 35090 Jhang GPO Punjab 35091 AHATA FAROOQIA 47066 Wah Cantt. GPO Punjab 47067 AHDI 47750 Gujar Khan GPO Punjab 47751 AHMAD NAGAR 52070 Gujranwala GPO Punjab 52071 AHMAD PUR EAST 63350 Bahawalpur GPO Punjab 63351 AHMADOON 96100 Quetta GPO Balochistan 96101 AHMADPUR LAMA 64380 Rahimyar Khan GPO Punjab 64381 AHMED PUR 66040 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66041 AHMED PUR 40120 Sargodha GPO Punjab 40121 AHMEDWAL 95150 Quetta GPO Balochistan 95151 -

National Freight and Logistics Policy

NATIONAL FREIGHT AND LOGISTICS POLICY Ministry of Communications Government of Pakistan Final, 28 April 2020 National Freight and Logistics Policy Government of Pakistan Table of Content 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................4 2. State of Pakistan’s Freight and Logistics Sector ...................................................................................6 3. Justification for the NFLP .........................................................................................................................9 3.1. Rationale .............................................................................................................................................9 3.2. Potential Benefits ............................................................................................................................. 11 4. Vision, Principles and Objectives ......................................................................................................... 12 4.1. Vision Statement .............................................................................................................................. 12 4.2. Objectives ......................................................................................................................................... 13 4.3. Principles .........................................................................................................................................