Biosphere Reserves in the Mountains of the World Excellence in the Clouds?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Navigating an Ethical Critique for a "New" Kind of War in Iraq Transcript

Origins Interviewer I’m going to ask you a little bit about West Point as we begin. So—and some of this is just merely what they call tagging to be able to—the camera’s running now—to be able to allow the transcriber to set this in a certain—according to certain search mechanisms. So, what class at West Point were you? Andrew Bacevich 1969. Interviewer 1. And you were—you come from where? Where did you grow up? Andrew Bacevich Indiana. Interviewer Indiana, so did I. Andrew Bacevich Oh, really? Where? Interviewer Yeah, Indianapolis, where we— Andrew Bacevich Okay, upstate, Calumet region, around Hammond and Highland and places like that. Interviewer And can you tell me just in general terms the various assignments that you had during your career, particularly your career in the military, but even going up to your academic career, just so we list off, and then we’ll get back to it. Andrew Bacevich Sure. I served as a commissioned officer for 23 years, short tour— after school, short tour at Fort Riley, deployed to Vietnam in the summer of 1970. Stayed there until the summer of 1971. In Vietnam, I served first with the 2nd Squadron, 1st Cavalry, and then the 1st Squadron, 10th Cavalry. When I came home, I was assigned to the 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment at Fort Bliss. The regiment moved—excuse me, at Fort Lewis, Washington, the regiment moved to Fort Bliss, and I moved with it. That’s where I commanded K Troop, 3rd Squadron, 3rd Cavalry. -

Assessment of Plant Diversity for Threat Elements: a Case Study of Nargu Wildlife Sanctuary, North Western Himalaya

Ceylon Journal of Science 46(1) 2017: 75-95 DOI: http://doi.org/10.4038/cjs.v46i1.7420 RESEARCH ARTICLE Assessment of plant diversity for threat elements: A case study of Nargu wildlife sanctuary, north western Himalaya Pankaj Sharma*, S.S. Samant and Manohar Lal G.B. Pant National Institute of Himalayan Environment and Sustainable Development, Himachal Unit, Mohal- Kullu-175126, H.P., India Received: 12/07/2016; Accepted: 16/02/2017 Abstract: Biodiversity crisis is being experienced losses, over exploitation, invasions of non-native throughout the world, due to various anthropogenic species, global climate change (IUCN, 2003) and and natural factors. Therefore, it is essential to disruption of community structure (Novasek and identify suitable conservation priorities in biodiversity Cleland, 2001). As a result of the anthropogenic rich areas. For this myriads of conservational pressure, the plant extinction rate has reached approaches are being implemented in various ecosystems across the globe. The present study has to137 species per day (Mora et al., 2011; Tali et been conducted because of the dearth of the location- al., 2015). At present, the rapid loss of species is specific studies in the Indian Himalayas for assessing estimated to be between 1,000–10,000 times the ‘threatened species’. The threat assessment of faster than the expected natural extinction rate plant species in the Nargu Wildlife Sanctuary (NWS) (Hilton-Taylor, 2000). Under the current of the northwest Himalaya was investigated using scenario, about 20% of all species are likely to Conservation Priority Index (CPI) during the present go extinct within next 30 years and more than study. -

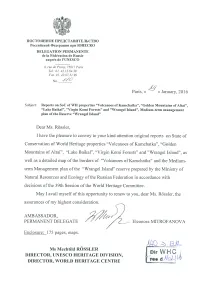

State of Conservation Report by The

REPORT ON THE CURRENT STATE OF CONSERVATION OF THE WORLD HERITAGE PROPERTIES VOLCANOES OF KAMCHATKA, GOLDEN MOUNTAINS OF ALTAI, LAKE BAIKAL, VIRGIN KOMI FORESTS, WRANGEL ISLAND IN 2015 Report On the State of Conservation of the UNESCO World Heritage Property Golden Mountains of Altai (Russian Federation, No. 768rev) SUMMARY Project works on construction of the Altai gas pipeline are not kept now. According to the legislation of the Russian Federation, without obtaining the positive conclusion of the state environmental assessment for project documentation the corresponding construction cannot be started. Project documentation on construction of the gas pipeline “Altai” did not arrive to the state environmental assessment of federal level. The order of the Russian Federation Government of August 13, 2013 No. 1416-r become invalid. The Government of Altai Republic has no plans for construction and reconstruction of linear constructions and other capital construction projects in borders of the object of the world heritage. The object of the world heritage continues to work on recommendations of UNESCO 2012 mission. In the territory of the World Heritage, the main violations of special protection order are connected with illegal stay in the territories of the reserves. Monitoring researches of a snow leopard and argali groups are conducted, field researches on identification of a reindeer summer habitats, works on the project "The organization of long-term monitoring system of climate changes and ecosystems of the reserve "Altaisky" are continued in the territory of the World Heritage. The increase of a tourist stream at the territory of the World Heritage is noted. In territories of national parks and natural parks of regional value, informative tourism is dated to the developed ecological routes. -

Journal of Alpine Research | Revue De Géographie Alpine

Journal of Alpine Research | Revue de géographie alpine 103-3 | 2015 Les territoires de montagne, fournisseurs mondiaux de ressources Impact of Conservation and Development on the Vicinity of Nanda Devi National Park in the North India Version française à paraître Pratiba Naitthani and Sunil Kainthola Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/rga/3100 DOI: 10.4000/rga.3100 ISSN: 1760-7426 Publisher Association pour la diffusion de la recherche alpine Electronic reference Pratiba Naitthani and Sunil Kainthola, « Impact of Conservation and Development on the Vicinity of Nanda Devi National Park in the North India », Journal of Alpine Research | Revue de géographie alpine [Online], 103-3 | 2015, Online since 02 March 2016, connection on 01 May 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/rga/3100 ; DOI : 10.4000/rga.3100 This text was automatically generated on 1 May 2019. La Revue de Géographie Alpine est mise à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Impact of Conservation and Development on the Vicinity of Nanda Devi National... 1 Impact of Conservation and Development on the Vicinity of Nanda Devi National Park in the North India Version française à paraître Pratiba Naitthani and Sunil Kainthola 1 The conservation of critical habitat is a priority issue and usually achieved by establishing national parks or wildlife sanctuaries. Equally important is the sustained supply of electricity for the metro areas and various industrial purposes. The Himalayas, which have high hydropower potential and a rich bio diversity, are the focus of both the hydropower and conservation sectors. -

Design & Development Of

Design & Development Of Involving Local Communities Bilal Habib Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, India It’s always further than it looks. It’s always taller than it looks. And it’s always harder than it looks.” Nanda Devi Peak CONTENTS 01 Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve 01 02 Biodiversity Features 03 03 Origin of Biosphere Reserves 05 04 UNESCO MAB Programme 06 05 Development of Monitoring Programme 07 06 Literature Review and Baseline Maps 07 07 Field Protocol (Sampling Design) 07 08 Field Protocol (Sampling Strategy) 12 09 Field Protocol (Data Collection Formats) 12 10 Data Format for Carnivore Species 13 11 Instructions for Carnivore Data Format 14 12 Data Format for Ungulate Species 18 13 Instructions for Prey Point Data Sheet 19 14 Statistical Analysis 20 15 Expected Outcomes 20 16 Recommendations and Learnings 20 17 Success of the Exercise 21 18 Key Reference 22 Design and Development of Ecological Monitoring Programme in Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve, Uttarakhand India, Involving Local Communities Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve: Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve (NBR) (30°05' - 31°02' N Latitude, 79012' - 80019' E Longitude) is located in the northern part of west Himalaya in the biogeographical classification zone 2B. The Biosphere Reserve spreads over three districts of Uttarakhand - Chamoli in Garhwal and Bageshwar and Pithoragarh in Kumaun. The Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve falls under Himalayan Highlands (2a) zone of the biogeographic zonation of India. It has wide altitudinal range (1,500 - 7,817 m). It covers 6407.03 km2 area with core zone (712.12 km2), buffer zone (5,148.57 km2) and transition zone (546.34 km2). -

УДК 595.789 Dubatolov VV1, Korb SK2, Yakovlev RV3,4 a REVIEW

Biological Bulletin of Bogdan Chmelnitskiy Melitopol State Pedagogical University 445 УДК 595.789 Dubatolov V.V.1, Korb S.K.2, Yakovlev R.V.3,4 A REVIEW OF THE GENUS TRIPHYSA ZELLER, 1858 (LEPIDOPTERA, SATYRIDAE) 1Institute of Systematics and Ecology of Animals, Siberian Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences, Frunze str. 11, Novosibirsk 630091 Russia. E-mail: [email protected] 2Russian Entomological Society, Nizhny Novgorod Division P.O.Box 97, Nizhny Novgorod 603009 Russia. E-mail: [email protected] 3Altai State University pr. Lenina 61, Barnaul, 656049, Russia, E-mail: [email protected] 4Tomsk State University, Laboratory of Biodiversity and Ecology Lenina pr. 36, 634050 Tomsk, Russia A review of the genus Triphysa Zeller, 1858 is presented. One new species Triphysa issykkulica sp.n. (type locality: Kazakhstan, W of Almaty, 800 m) and 8 new subspecies are described: Triphysa phryne kasikoporana ssp. n. (type locality: Kasikoporan [NE Turkey, Agri prov.]), Triphysa striatula urumtchiensis ssp. n. (type locality: Urumtchi), Triphysa issykkulica pljustchi ssp. n. (type locality: W. Kirgiziya, Talasskii Mts., Manas), Triphysa nervosa tuvinica ssp. n. (type locality: N. Tuva, near Kyzyl, Tuge Mt.), Triphysa nervosa arturi ssp. n. (type locality: S. Tuva, 15 km WSW Erzin), Triphysa nervosa kobdoensis ssp. n. (type locality: W. Mongolia, Hovd aimak, 15 km S Khara-Us-Nuur lake, 1300 m), Triphysa nervosa mongolaltaica ssp. n. (type locality: Mongolia, Hovd aimak, Bulgan-Gol basin, middle stream of Ulyasutai- Gol river, 2500−3000 m) and Triphysa nervosa brinikhi ssp. n. (type locality: Russia, Chita Reg., Onon distr., 18 km WSW Nizhniy Zasuchey vill., Butyvken lake, Pinus forest, steppe) are described. -

National Ganga River Basin Authority (Ngrba)

NATIONAL GANGA RIVER BASIN AUTHORITY (NGRBA) Public Disclosure Authorized (Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India) Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) Public Disclosure Authorized Volume I - Environmental and Social Analysis March 2011 Prepared by Public Disclosure Authorized The Energy and Resources Institute New Delhi i Table of Contents Executive Summary List of Tables ............................................................................................................... iv Chapter 1 National Ganga River Basin Project ....................................................... 6 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................................. 6 1.2 Ganga Clean up Initiatives ........................................................................... 6 1.3 The Ganga River Basin Project.................................................................... 7 1.4 Project Components ..................................................................................... 8 1.4.1.1 Objective ...................................................................................................... 8 1.4.1.2 Sub Component A: NGRBA Operationalization & Program Management 9 1.4.1.3 Sub component B: Technical Assistance for ULB Service Provider .......... 9 1.4.1.4 Sub-component C: Technical Assistance for Environmental Regulator ... 10 1.4.2.1 Objective ................................................................................................... -

Rajaji National Park

Rajaji National Park drishtiias.com/printpdf/rajaji-national-park Why in News Recently, a clash took place between Van Gujjars and the Uttarakhand forest officials in the Rajaji National Park. Key Points Location: Haridwar (Uttarakhand), along the foothills of the Shivalik range, spans 820 square kilometres. Background: Three sanctuaries in the Uttarakhand i.e. Rajaji, Motichur and Chila were amalgamated into a large protected area and named Rajaji National Park in the year 1983 after the famous freedom fighter C. Rajgopalachari; popularly known as “Rajaji”. Features: This area is the North Western Limit of habitat of Asian elephants. Forest types include sal forests, riverine forests, broad–leaved mixed forests, scrubland and grassy. It possesses as many as 23 species of mammals and 315 bird species such as elephants, tigers, leopards, deers and ghorals, etc. It was declared a Tiger Reserve in 2015. It is home to the Van Gujjars in the winters. Van Gujjars: It is one of the few forest-dwelling nomadic communities in the country. Usually, they migrate to the bugyals (grasslands) located in the upper Himalayas with their buffaloes and return only at the end of monsoons to their makeshift huts, deras, in the foothills. They inhabit the foothills of Himalayan states like Himachal Pradesh, Uttrakhand. They traditionally practice buffalo husbandry; a family owns up to 25 heads of buffaloes. They rely on buffaloes for milk, which gets them a good price in Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh markets. 1/2 Other Protected Areas in Uttarakhand: Jim Corbett National Park (first National Park of India). Valley of Flowers National Park and Nanda Devi National Park which together are a UNESCO World Heritage Site. -

RCN #33 21/8/03 13:57 Page 1

RCN #33 21/8/03 13:57 Page 1 No. 33 Summer 2003 Special issue: The Transformation of Protected Areas in Russia A Ten-Year Review PROMOTING BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION IN RUSSIA AND THROUGHOUT NORTHERN EURASIA RCN #33 21/8/03 13:57 Page 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS Voice from the Wild (Letter from the Editors)......................................1 Ten Years of Teaching and Learning in Bolshaya Kokshaga Zapovednik ...............................................................24 BY WAY OF AN INTRODUCTION The Formation of Regional Associations A Brief History of Modern Russian Nature Reserves..........................2 of Protected Areas........................................................................................................27 A Glossary of Russian Protected Areas...........................................................3 The Growth of Regional Nature Protection: A Case Study from the Orlovskaya Oblast ..............................................29 THE PAST TEN YEARS: Making Friends beyond Boundaries.............................................................30 TRENDS AND CASE STUDIES A Spotlight on Kerzhensky Zapovednik...................................................32 Geographic Development ........................................................................................5 Ecotourism in Protected Areas: Problems and Possibilities......34 Legal Developments in Nature Protection.................................................7 A LOOK TO THE FUTURE Financing Zapovedniks ...........................................................................................10 -

Their Uses and Degrees of Risk of Extinc

Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 28 (2021) 3076–3093 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences journal homepage: www.sciencedirect.com Original article Medicinal plants resources of Western Himalayan Palas Valley, Indus Kohistan, Pakistan: Their uses and degrees of risk of extinction ⇑ Mohammad Islam a, , Inamullah a, Israr Ahmad b, Naveed Akhtar c, Jan Alam d, Abdul Razzaq c, Khushi Mohammad a, Tariq Mahmood e, Fahim Ullah Khan e, Wisal Muhammad Khan c, Ishtiaq Ahmad c, ⇑ Irfan Ullah a, Nosheen Shafaqat e, Samina Qamar f, a Department of Genetics, Hazara University, Mansehra 21300, KP, Pakistan b Department of Botany, Women University, AJK, Pakistan c Department of Botany, Islamia College University, 25120 KP, Peshawar, Pakistan d Department of Botany, Hazara University, Mansehra 21300, KP, Pakistan e Department of Agriculture, Hazara University, Mansehra, KP, Pakistan f Department of Zoology, Govt. College University, Faisalabad, Pakistan article info abstract Article history: Present study was intended with the aim to document the pre-existence traditional knowledge and eth- Received 29 December 2020 nomedicinal uses of plant species in the Palas valley. Data were collected during 2015–2016 to explore Revised 10 February 2021 plants resource, their utilization and documentation of the indigenous knowledge. The current study Accepted 14 February 2021 reported a total of 65 medicinal plant species of 57 genera belonging to 40 families. Among 65 species, Available online 22 February 2021 the leading parts were leaves (15) followed by fruits (12), stem (6) and berries (1), medicinally significant while, 13 plant species are medicinally important for rhizome, 4 for root, 4 for seed, 4 for bark and 1 each Keywords: for resin. -

Tabelle Naturparke in Deutschland, Pdf-Datei

Naturparke in Deutschland (Stand: 01.10.2020) lfd. Nr. Name (Land) Fläche [ha] Großlandschaften *) Kurzcharakterisierung/Lebensräume 1 Schlei (SH) 49790 NWT Küste, Förde, Brackwassergewässer, abwechslungsreiches Hügelland 2 Hüttener Berge (SH) 21900 NWT Eiszeitlich geprägte Kulturlandschaft mit Knicks, kleineren Flüssen, Seen (Wittensee) und Auen 3 Westensee (SH) 25000 NWT Seen, Wiesen, Erlenbruchwälder, Knicks und Moore 4 Aukrug (SH) 38400 NWT Niederungs-, Teich- und (Laub)Waldlandschaft der Geest 5 Holsteinische Schweiz (SH) 75900 NWT Jungmoränenlandschaft mit Knicks, Seen (z.B. Großer Plöner See), Buchenwäldern 6 Insel Usedom (MV) 59012 NOT Ostsee-Insel mit eiszeitlich geprägtem Landschaftsmosaik 7 Lauenburgische Seen (SH) 47400 NWT, NOT Seen (Schaalsee und Ratzeburger See), Knicks, alte Alleen, Buchenwälder, Moore 8 Sternberger Seenland (MV) 53990 NOT Bewaldete Sanderflächen, Urstromtäler, Hügellandschaften und große Seen 9 Nossentiner/Schwinzer Heide (MV) 35500 NOT Kiefernwälder, Moore, Seen, Dünen, Trockenrasen 10 Mecklenburgische Schweiz und Kummerower See 61592 NOT Jungmoränen-Kulturlandschaft mit dichtem Feuchtgebietsnetz, Wald (MV) 11 Flusslandschaft Peenetal (MV) 33390 NOT Fließgewässer mit Flußtalmoorkomplex im Mündungsbereich 12 Am Stettiner Haff (MV) 55300 NOT Dünenlandschaft mit artenreichen Trockenrasen, Buchen- und Mischwäldern, Feuchtwiesen und Moore 13 Feldberger Seenlandschaft (MV) 34700 NOT Zahlreiche Klarwasserseen, saure, nährstoffreiche Kesselmoore, alte Buchenwälder ("Heilige Hallen"), Kiefernwälder 14 Lüneburger -

Protected Areas in News

Protected Areas in News National Parks in News ................................................................Shoolpaneswar................................ (Dhum- khal)................................ Wildlife Sanctuary .................................... 3 ................................................................... 11 About ................................................................................................Point ................................Calimere Wildlife Sanctuary................................ ...................................... 3 ......................................................................................... 11 Kudremukh National Park ................................................................Tiger Reserves................................ in News................................ ....................................................................... 3 ................................................................... 13 Nagarhole National Park ................................................................About................................ ......................................................................................................................................... 3 .................................................................... 14 Rajaji National Park ................................................................................................Pakke tiger reserve................................................................................. 3 ...............................................................................