Potter Building Designation Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Borough Hall Skyscraper Historic District Designation Report

Cover Photograph: Court Street looking south along Skyscraper Row towards Brooklyn City Hall, now Brooklyn Borough Hall (1845-48, Gamaliel King) and the Brooklyn Municipal Building (1923-26, McKenzie, Voorhees & Gmelin). Christopher D. Brazee, 2011 Borough Hall Skyscraper Historic District Designation Report Prepared by Christopher D. Brazee Edited by Mary Beth Betts, Director of Research Photographs by Christopher D. Brazee Map by Jennifer L. Most Technical Assistance by Lauren Miller Commissioners Robert B. Tierney, Chair Pablo E. Vengoechea, Vice-Chair Frederick Bland Christopher Moore Diana Chapin Margery Perlmutter Michael Devonshire Elizabeth Ryan Joan Gerner Roberta Washington Michael Goldblum Kate Daly, Executive Director Mark Silberman, Counsel Sarah Carroll, Director of Preservation TABLE OF CONTENTS BOROUGH HALL SKYSCRAPER HISTORIC DISTRICT MAP ................... FACING PAGE 1 TESTIMONY AT THE PUBLIC HEARING ................................................................................ 1 BOROUGH HALL SKYSCRAPER HISTORIC DISTRICT BOUNDARIES ............................. 1 SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................... 3 THE HISTORICAL AND ARCHITECTURAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE BOROUGH HALL SKYSCRAPER HISTORIC DISTRICT ........................................................................................ 5 Early History and Development of Brooklyn‟s Civic Center ................................................... 5 Mid 19th Century Development -

Forest Avenue and Stevens Avenue Portland, Maine Historic Context

Forest Avenue and Stevens Avenue Portland, Maine Historic Context Scott T. Hanson Sutherland Conservation & Consulting August 2015 General context Development of Colonial Falmouth European settlement of the area that became the city of Portland, Maine, began with English settlers establishing homes on the islands of Casco Bay and on the peninsula known as Casco Neck in the early seventeenth century. As in much of Maine, early settlers were attracted by abundant natural resources, specifically fish and trees. Also like other early settlement efforts, those at Casco Bay and Casco Neck were tenuous and fitful, as British and French conflicts in Europe extended across the Atlantic to New England and both the French and their Native American allies frequently sought to limit British territorial claims in the lands between Massachusetts and Canada. Permanent settlement did not come to the area until the early eighteenth century and complete security against attacks from French and Native forces did not come until the fall of Quebec to the British in 1759. Until this historic event opened the interior to settlement in a significant way, the town on Casco Neck, named Falmouth, was primarily focused on the sea with minimal contact with the interior. Falmouth developed as a compact village in the vicinity of present day India Street. As it expanded, it grew primar- ily to the west along what would become Fore, Middle, and Congress streets. A second village developed at Stroudwater, several miles up the Fore River. Roads to the interior were limited and used primarily to move logs to the coast for sawing or use as ship’s masts. -

AMERICAN TRACT SOCIETY BUILDING, 150 Nassau Street (Aka 144-152 Nassau Street and 2-6 Spruce Street), Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission June 15, 1999, Designation List 306 LP-2038 AMERICAN TRACT SOCIETY BUILDING, 150 Nassau Street (aka 144-152 Nassau Street and 2-6 Spruce Street), Manhattan. Built 1894-95; Robert Henderson Robertson, architect; William W. Crehore, engineering consultant; John Downey, Atlas Iron Construction Co., and Louis Weber Building Co., builders. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 100, Lot 3.1 On March 16, 1999, the Landmarks Presetvation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the American Tract Society Building (Item No. 2). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. A representative of the building's owner stated that they were not opposed to designation. Three people spoke in favor of designation, including representatives of the New York Landmarks Consetvancy and the Historic Districts Council. In addition, the Commission received several letters in support of designation. Summary The American Tract Society Building, at the __. .. - ··· r -r1 southeast comer of Nassau and Spruce Streets, was . \ " Ll-1 constructed in 1894-95 to the design of architect R. H. _ _-r4 I 1! .li,IT! J . Robertson, who was known for his churches and institutional and office buildings in New York. It is one of the earliest, as well as one of the earliest extant, steel skeletal-frame skyscrapers in New York, partially of curtain-wall construction. This was also one of the city's tallest and largest skyscrapers upon its completion. Twenty full stories high (plus cellar, basement, and th.ree-story tower) and clad in rusticated gray Westerly granite, gray Haverstraw Roman brick, and buff-colored terra cotta, the building was constructed with a U-shaped plan, having an exterior light court. -

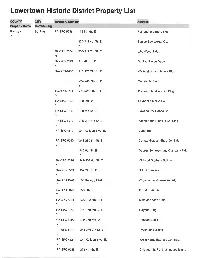

Lowertown Historic District Property List

Lowertown Historic District Property List COUNTY CITY Inventory Number Address Property Name Contributing Ramsey St. Paul RA-SPC-5246 176 5th St. E. Railroad and Bank Bldg. y 205-213 4th St. E. Samco Sportswear Co. y RA-SPC-5364 208-212 7th St. E. J.H. Weed Bldg. N RA-SPC-5225 214 4th St. E. St. Paul Union Depot y RA-SPC-7466 216-220 7th St. E. Walterstroff and Montz Bldg. y 224-240 7th St. E. Constants Block y RA-SPC-5271 227-231 6th St. E. Konantz Saddlery Co. Bldg. y RA-SPC-5248 230 5th St. E. Fairbanks-M orse Co. y RA-SPC-5249 230 5th St. E. Power's Dry Goods Co. y RA-SPC-5272 235-237 6th St. E. Koehler and Hinricks Co. Bldg. y RA-SPC-4519 241 Kellogg Blvd. E. Depot Bar N RA-SPC-5250 242-280 5th St. E. Conrad Gotzian Shoe Co. Bldg. y 245 6th St. E. George Sommers and Company Bldg. y RA-SPC-5226 249-253 4th St. E. Michaud Brothers Building y RA-SPC-5369 252 7th St. E. B & M Furniture y RA-SPC-4520 255 Kellogg Blvd. E. Weyerhauser-Denkman Bldg. y RA-SPC-5370 256 7th St. E. B & M Furniture y RA-SPC-5251 258-260 5th St. E. Mike and Vic's Cafe y RA-SPC-5252 261-279 5th St. E. Rayette Bldg. y RA-SPC-5227 262-270 4th St. E. Hackett Block y RA-SPC-5371 264-266 7th St. E. O'Connor Bu ilding y RA-SPC-4521 271 Kellogg Blvd. -

Qouprttyuatt : Mr 'Fl Tbo Forms Cut from Brewer, Hater, Charlis, Frum Broadway

Barberi A DUbrow, from i8T Broom it to 68 War- - Chryitle,WN, to 164 W 48tK. Green, Tj,jrorfciqM WUrtW84Brws,, , A 25 ...,. B v i; Christie Janney, from Nassan it Green, JWM, from Dey ijtftsoTBer,RJ9Tch iqa ,7sVoi1THNED.1IjTO. I Hifaa4..at.tOf W .,.,, MAY-DA-Y TaWB;Wm, from 18 John it to M Maiden laneJ m 'Bilfir!tfiTel;riTriffB'ro-'M'Jhrl'tiitn- t, hkim fff?VeiBT'Olr dfOO V l'in wtnsl ....'f BnffS rlD(omin7aaliamUi.iaCi, Irom.l f,. m,i MOVERS? Barter? Patrlclt, from 320 W 18th st to 812 W Ciairmnnt, Estelle, lrom 111 W roth to 110 Wlit Early, K from 61S W 21st to $13 10th ave. Green, W B, from 1 B'wav to 78 William Slalden lane. J, it 83 140it Co, ! Broadway. Clapp A Co, from M New st to 58 liroadway. Earnest, 8. from 536 to 631 Broadway. Greenbaum, A, from W Houston it to E 84th. Interim onai rrintln Tel to NEUVOtTH, GLOOMY AND IMcr-Ocea- Bldg to DEPItnaiEB, 111 to 171 Broadway. Clark, O 11, to 403 W 25tn 10 Greenbsnm, J, from 91 Grind it to 44 Greeno n Improvement Co, from rotter Barlow Inace Burvejs, from st Easton, It T B, from Spruce at to Equitable Bldg. it. V Barnard, 8, to lni W lOlta iU Clark, Kd, from 801 W 2sth st to 5 Oardon row. Echold A Miller, from C20 to C2S Broadway, Greenbaum A Itosenthal, from 91 Grand it to 44 Mutual Lite Bl Ijr. TUB BTOIt OV THOUSANDS. 415 W 83d 843 224 W STth & to 514 W SOth ft. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-11018 (Rev. 10-90) • United States Department of the Interior• National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting detenninations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification. materials. and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and. narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter. word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name MORSE HARDWARE COMPANY BUILDING other names/site number N/A 2. Location street & number 1023-1025North State Street not for publication N/A city or town Bellingham vicinity N/A state Washington code WA county Whatcom code 073 zip code 98225 3. State/Federal Agency Certification WASHINGTON STATE HISTORIC PRESERV AnON OFFICE State or Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register criteria. (_ See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature of commenting or other official Date State or Federal agency and bureau 4. National Park Service Certification I, hereby certify that this property is: Signature of Keeper: Date of Action: __ entered in the National Register _ See continuation sheet. -

The Configuration of the Rock Floor of Greater New York

Bulletin No. 270 . Series B, Descriptive Geology, 73 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES D. VVALCOTT, DIHECTOK THE CONFIGURATION OF THE ROCK FLOOR OF GREATER NEW YORK BY WILLIAM HERBERT HOBBS WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT. PRINTING OFFICE 1905 CONTENTS. Page. LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL .................................................. 7 PART I. STRUCTURAL STUDIES ............................................. .9 Introduction......................................................... 9 Aids to geological studies on Manhattan Island..................... 9 Engineering enterprises that have pierced the rock floor............ 10 Keview of structural geological studies of the New York City area.... 12 Boroughs of Manhattan and the Bronx ........................ 12 Gale .................................................... 12 Mather.................................................. 12 Cozzens ................................................. 12 Stevens.................................................. 12 Credner................................................. 13 Newberry ............................................... 13 Dana.................................................... 14 Russell.................................................. 14 Kemp ................................................... 14 Merrill .................................................. 15 Eckel ................................................... 16 Gratacap ................................................ '16 Julien ..................... i............................. -

Residential Development and Population Growth Updated July 2014 Summary 1990 2000 2013 2015 Units 7,400 13,046 30,500 32,000 Population* 13,675 22,900 61,000 64,000

Residential Development and Population Growth Updated July 2014 Summary 1990 2000 2013 2015 Units 7,400 13,046 30,500 32,000 Population* 13,675 22,900 61,000 64,000 *Estimate based on number of units using 1.76 average HH size through 2006 and 2.0 average HH size as of Jan 2007 (Sources: Downtown Alliance Residential Survey, US Census Data) EXISTING BUILDINGS Address Building Name Lease Type Building Type Units Date Open 1 Beekman Street Not Available Conversion 1 N/A 109 Washington Street Rental Conversion 16 N/A 112-114 Chambers Street Rental Conversion 7 N/A 120 Water Street Not Available Conversion 4 N/A 127 Fulton Street Condo Conversion 9 N/A 137 Greenwich Street Rental 8 N/A 142-144 Beekman Street Not Available Conversion 1 N/A 15 Warren Street Not Available Conversion 3 N/A 162 Chambers Street Rental Conversion 6 N/A 164 William Street Not Available Conversion 1 N/A 191-195 Front Street Rental New Construction 6 N/A 244 Front Street Not Available Conversion 6 N/A 252 Front Street Not Available Conversion 2 N/A 259 Front Street Not Available Conversion 3 N/A 261 Broadway Co-Op Conversion 65 N/A 261 Water Street Not Available Conversion 20 N/A 270 Water Street Rental Conversion 8 N/A 28 Warren Street Not Available Conversion 1 N/A 28 Water Street Not Available Conversion 1 N/A 330 Pearl Street Rental Conversion 10 N/A 42 Water Street Rental Conversion 3 N/A 44 John Street Rental Conversion 1 N/A 59 Warren Street Not Available Conversion 8 N/A 61-75 West Broadway Not Available Conversion 8 N/A 94 Greenwich Street Not Available Conversion -

Cleveland Architects Herman Albrecht

Cleveland Landmarks Commission Cleveland Architects Herman Albrecht Birth/Established: March 26, 1885 Death/Disolved: January 9, 1961 Biography: Herman Albrecht worked as a draftsman for the firm of Howell & Thomas. He formed the firm of Albrecht, Wilhelm & Kelly 1918 with Karl Wilhelm of Massillon and John S. Kelly of Cleveland. John Kelly left the firm in 1925 and it was knwon Albrecht & Wilhelm from 1925 until 1933. It was later known Albrecht, Wilhelm, Nosek & Frazen. Herman Albrecht was a native of Massillon. The firm, which maintained offices in both Cleveland and Massillon and was responsible for 700 commissions that are found in Cleveland suburbs of Lakewood, Rocky River, Shaker Heights; and in Massillon, Canton, Alliance, Dover, New Philadelphia, Mansfield, Wooster, Alliance and Warren, Ohio. Albrecht, Wilhelm & Kelly Birth/Established: 1918 Death/Disolved: 1925 Biography: The firm Albrecht, Wilhelm & Kelly was formed in 1918 with Herman Albrecht of Cleveland, Karl Wilhelm of Massillon and John S. Kelly of Cleveland. John Kelly left the firm in 1925 and it was knwon Albrecht & Wilhelm from 1925 until 1933. It was later known Albrecht, Wilhelm, Nosek & Frazen. The firm, which maintained offices in both Cleveland and Massillon. Building List Structure Date Address City State Status Koch Building unk Alliance OH Quinn Residence 1925 Canton OH Standing T.K. Harris Residence 1926 Canton OH Standing William H. Pacell Residence 1919 Alliance OH Standing Meyer Altschuld Birth/Established: 1879 Death/Disolved: unknown Biography: Meyer Altschuld was Polish-born, Yiddish speaking, and came to the United States in 1904. He was active as a Cleveland architect from 1914 to 1951. -

Brief Biographies of American Architects Who Died Between 1897 and 1947

Brief Biographies of American Architects Who Died Between 1897 and 1947 Transcribed from the American Art Annual by Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr., Director, Maine Historic Preservation Commission. Between 1897 and 1947 the American Art Annual and its successor volume Who's Who in American Art included brief obituaries of prominent American artists, sculptors, and architects. During this fifty-year period, the lives of more than twelve-hundred architects were summarized in anywhere from a few lines to several paragraphs. Recognizing the reference value of this information, I have carefully made verbatim transcriptions of these biographical notices, substituting full wording for abbreviations to provide for easier reading. After each entry, I have cited the volume in which the notice appeared and its date. The word "photo" after an architect's name indicates that a picture and copy negative of that individual is on file at the Maine Historic Preservation Commission. While the Art Annual and Who's Who contain few photographs of the architects, the Commission has gathered these from many sources and is pleased to make them available to researchers. The full text of these biographies are ordered alphabetically by surname: A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W Y Z For further information, please contact: Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr., Director Maine Historic Preservation Commission 55 Capitol Street, 65 State House Station Augusta, Maine 04333-0065 Telephone: 207/287-2132 FAX: 207/287-2335 E-Mail: [email protected] AMERICAN ARCHITECTS' BIOGRAPHIES: ABELL, W. -

Landmarks Preservation Commission November 16, 2010, Designation List 435 LP-2390

Landmarks Preservation Commission November 16, 2010, Designation List 435 LP-2390 PAUL RUDOLPH PENTHOUSE & APARTMENTS, 23 Beekman Place, Manhattan. Built late 1860s; facade altered 1929-30, Franklin Abbott, architect; penthouse and rear facade 1977-82, Paul Rudolph, architect. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1361, Lot 118. On November 17, 2009, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a hearing on the proposed designation of the Paul Rudolph Penthouse & Apartments and the proposed designation of the related Landmarks Site (Item No. 5). Three people spoke in favor of designation, including representatives of Docomomo New York/Tri-State, the Historic Districts Council, and the Paul Rudolph Foundation. Community Board No. 6 took no position at this time and a representative of the owner of the property requested that the public record remain open for a period of thirty days. Summary Paul Rudolph, one of the most celebrated and innovative American architects of the 20th century, was associated with 23 Beekman Place for more than 35 years, from 1961 until his death in 1997. Trained at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in the 1940s, Rudolph was a second-generation modernist who grew dissatisfied with functional aesthetics but remained committed to exploiting industrial materials to create structures of great formal complexity. From 1958 to 1965, he served as chairman of the Department of Architecture at Yale University, where he designed the well-known Art and Architecture Building, now called Paul Rudolph Hall. Rudolph began leasing an apartment on the fourth floor of 23 Beekman Place in 1961, which became his full-time residence in 1965. -

LCSH Section O

O, Inspector (Fictitious character) O-erh-kʾun Ho (Mongolia) O-wee-kay-no Indians USE Inspector O (Fictitious character) USE Orhon River (Mongolia) USE Oowekeeno Indians O,O-dimethyl S-phthalimidomethyl phosphorodithioate O-erh-kʾun River (Mongolia) O-wen-kʻo (Tribe) USE Phosmet USE Orhon River (Mongolia) USE Evenki (Asian people) O., Ophelia (Fictitious character) O-erh-to-ssu Basin (China) O-wen-kʻo language USE Ophelia O. (Fictitious character) USE Ordos Desert (China) USE Evenki language O/100 (Bomber) O-erh-to-ssu Desert (China) Ō-yama (Kanagawa-ken, Japan) USE Handley Page Type O (Bomber) USE Ordos Desert (China) USE Ōyama (Kanagawa-ken, Japan) O/400 (Bomber) O family (Not Subd Geog) O2 Arena (London, England) USE Handley Page Type O (Bomber) Ó Flannabhra family UF North Greenwich Arena (London, England) O and M instructors USE Flannery family BT Arenas—England USE Orientation and mobility instructors O.H. Ivie Reservoir (Tex.) O2 Ranch (Tex.) Ó Briain family UF Ivie Reservoir (Tex.) BT Ranches—Texas USE O'Brien family Stacy Reservoir (Tex.) OA (Disease) Ó Broin family BT Reservoirs—Texas USE Osteoarthritis USE Burns family O Hine Hukatere (N.Z.) OA-14 (Amphibian plane) O.C. Fisher Dam (Tex.) USE Franz Josef Glacier/Kā Roimata o Hine USE Grumman Widgeon (Amphibian plane) BT Dams—Texas Hukatere (N.Z.) Oa language O.C. Fisher Lake (Tex.) O-kee-pa (Religious ceremony) USE Pamoa language UF Culbertson Deal Reservoir (Tex.) BT Mandan dance Oab Luang National Park (Thailand) San Angelo Lake (Tex.) Mandan Indians—Rites and ceremonies USE ʻUtthayān hǣng Chāt ʻŌ̜p Lūang (Thailand) San Angelo Reservoir (Tex.) O.L.