Forest Avenue and Stevens Avenue Portland, Maine Historic Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Group Charter Coach Bus Parking

Greater Portland 22 MOTOR COACHSaco St Driverʼs Guide25 to Greater Portland Spring St Westbrook 302 Map Parking Key Cummings Rd Riverside St 114 Running Hill Rd Maine Turnpike 95 Exit Warren Av 45 95 Maine Mall Rd e Johnson Rd WestbrookFore Rive St r Capisic St URP e Portland Sanctuary Auburn St The Av University of MOTOR COACH- UNRESTRICTED PARKING stern International Stevens Ave Maine Mall We Jetport Woodfords St New England Allen Ave FRIENDLY STREETS FOR ALL VEHICLES Payne Rd Foden Rd Gorham Rd e WEST COMMERCIAL ST.Falmouth Mussey Rd Jetport Plaza Brighton Ave Reed St Kaplan Stevens Av Dartmouth St Forest Ave Canco St Clarks Pond Rd University St. John St MARGINAL WAY Congress St Ocean Ave Ave Vannah St Plowman St. to Cove St. EXIT SP Falmouth St NORTH 5 Deering DO EXIT BOUND Baxter Blvd 9 4 ONLY University of Payson 295 Hadlock Southern Maine Park Wash P Field EXIT Portland Deering Oaks Bedford St 6A i Veterans Bridge Park n SDO Expo Back Cove gt Park Avenue o 295 n Ave Lincoln St Post Fore River Parkway Veranda St Evans St Office Vaughn St t Portland St Marginal Wa SOUTH 1 S EXIT EXIT BOUND 8 Western Promenade State Cumberland Ave 7 ONLY Paris St y 295 DROP OFF Broadway COMMERCIAL ST. URP UNLIMITED TIME Spring St High St Long Wharf Danforth St Preble St PORTLAND PARKING Forest Ave Oak St Cumberland Ave Fore River DANFORTH ST. DO DO . COMMERCIAL ST. Congress St Victoria Mansion East & West of Center St. Fox St Elm St Anderson St. -

MOG Biography

Dictionary of Canadian Biography MOG (Heracouansit, Warracansit, Warracunsit, Warrawcuset), a noted warrior, subchief, and orator of the Norridgewock (Caniba) division of the Abenakis, son of Mog, an Abenaki chief killed in 1677; b. c. 1663; killed 12 Aug. 1724 (O.S.) at Norridgewock (Narantsouak; now Old Point in south Madison, Me). In the La Chasse* census of 1708, Mog is listed under the name Heracouansit (in Abenaki, welákwansit, “one with small handsome heels”). During King William’s and Queen Anne’s Wars Mog took part in the numerous raids on English settlements by Abenakis and carried captives and scalps to Quebec. Following the peace of Utrecht in April 1713, Mog, Bomoseen, Moxus, Taxous, and other chiefs concluded a peace with New England at Portsmouth, N.H., on 11– 13 July. The Abenakis pledged allegiance to Anne, though “it is safe to say that they did not know what the words meant” (Parkman). They also admitted the right of the English to land occupied before the war. The English, on their side, promised that the Indians could settle any individual grievances with them in English courts. Mog and the others then sailed with six New England commissioners to Casco Bay, where the treaty and terms of submission were read to 30 chiefs, in the presence of 400 other Abenakis, on 18 July. “Young Mogg” was described as “a man about 50 years, a likely Magestick lookt Man who spake all was Said.” The Abenakis expressed surprise when told that the French had surrendered all the Abenaki lands to the English: “wee wonder how they would give it away without asking us, God having at first placed us there and They having nothing to do to give it away.” Father Sébastien RALE, the Jesuit missionary at Norridgewock, reported a month later that he had convinced the Indians the English were deceiving them with an ambiguous phrase, for England and France still disagreed about the limits of “Acadia.” Apparently the Indians remained disturbed, however, when the English offered to show them the official text of the European treaty in the presence of their missionaries. -

Borough Hall Skyscraper Historic District Designation Report

Cover Photograph: Court Street looking south along Skyscraper Row towards Brooklyn City Hall, now Brooklyn Borough Hall (1845-48, Gamaliel King) and the Brooklyn Municipal Building (1923-26, McKenzie, Voorhees & Gmelin). Christopher D. Brazee, 2011 Borough Hall Skyscraper Historic District Designation Report Prepared by Christopher D. Brazee Edited by Mary Beth Betts, Director of Research Photographs by Christopher D. Brazee Map by Jennifer L. Most Technical Assistance by Lauren Miller Commissioners Robert B. Tierney, Chair Pablo E. Vengoechea, Vice-Chair Frederick Bland Christopher Moore Diana Chapin Margery Perlmutter Michael Devonshire Elizabeth Ryan Joan Gerner Roberta Washington Michael Goldblum Kate Daly, Executive Director Mark Silberman, Counsel Sarah Carroll, Director of Preservation TABLE OF CONTENTS BOROUGH HALL SKYSCRAPER HISTORIC DISTRICT MAP ................... FACING PAGE 1 TESTIMONY AT THE PUBLIC HEARING ................................................................................ 1 BOROUGH HALL SKYSCRAPER HISTORIC DISTRICT BOUNDARIES ............................. 1 SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................... 3 THE HISTORICAL AND ARCHITECTURAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE BOROUGH HALL SKYSCRAPER HISTORIC DISTRICT ........................................................................................ 5 Early History and Development of Brooklyn‟s Civic Center ................................................... 5 Mid 19th Century Development -

Re-Membering Norridgewock Stories and Politics of a Place Multiple

RE-MEMBERING NORRIDGEWOCK STORIES AND POLITICS OF A PLACE MULTIPLE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Ashley Elizabeth Smith December 2017 © 2017 Ashley Elizabeth Smith RE-MEMBERING NORRIDGEWOCK STORIES AND POLITICS OF A PLACE MULTIPLE Ashley Elizabeth Smith, Ph. D. Cornell University 2017 This dissertation is an ethnography of place-making at Norridgewock, the site of a famous Wabanaki village in western Maine that was destroyed by a British militia in 1724. I examine how this site is variously enacted as a place of Wabanaki survivance and erasure and ask, how is it that a particular place with a particular history can be mobilized in different and even contradictory ways? I apply Annemarie Mol’s (2002) analytic concept of the body multiple to place to examine how utilize practices of storytelling, remembering, gathering, producing knowledge, and negotiating relationships to variously enact Norridgewock as a place multiple. I consider the multiple, overlapping, coexistent, and contradictory enactments of place and engagements with knowledge that shape place-worlds in settler colonial nation-states. Rather than taking these different enactments of place to be different perspectives on or versions of place, I examine how these enactments are embedded in and shaped by hierarchies of power and politics that produce enactments of place that are at times parallel and at times contradictory. Place-making is especially political in the context of settler colonialism, where indigenous places, histories, and peoples are erased in order to be replaced (Wolfe 2006; O’Brien 2010). -

Portland Parks Commission Report October 2016 – May 2018

Portland Parks Commission Report October 2016 – May 2018 Prepared By: PORTLAND PARKS COMMISSION & PORTLAND DEPARTMENT OF PARKS, RECREATION, AND FACILITIES All photos in the report courtesy of: http://www.portlandmaine.gov/gallery.aspx?AID=26 http://portlandprf.com/1063/Parks 2 Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Message from the Chair of the Parks Commission ............................................................... 4 1.2 Background to the Annual Report......................................................................................... 5 2. PORTLAND PARKS COMMISSION ................................................................................................ 6 2.1 Mission and Organization...................................................................................................... 6 2.2 Members of the Park Commission ........................................................................................ 7 2.3 Planning and Vision ............................................................................................................... 8 2.4 Subcommittees of the Park Commission ............................................................................ 11 2.5 Projects Reviewed by the Parks Commission ..................................................................... 13 3. DEPARTMENT OF PARKS, RECREATION, AND FACILITIES ......................................................... 17 3.1 -

WHO WE ARE: SEE PAGE 7 Hilary Bassett SEE PAGE 10

SPRING 2019 n VOL. 44, NO. 2 n FREE LANDMARKS OBSERVER Historic character enriches our lives OBSERVATORY: New Visitor Experience SEE PAGE 4 THE CASE FOR MUNJOY HILL SEE PAGE 8 FLAG DAY: Friday, June 14 10 am – 7 pm WHO WE ARE: SEE PAGE 7 Hilary Bassett SEE PAGE 10 Page 8 PHOTO: RHONDA FARNHAM RHONDA PHOTO: LETTER FROM HILARY BASSETT, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR ODAY, AS I DRIVE UP FORE STREET and walk you to preserve the historic character of the place we call home. around my neighborhood, Munjoy Hill, the sounds of Imagine for a moment, how different this place would be if not construction are everywhere – hammers, power tools, for Landmarks and the tireless commitment of its hundreds and yes, backhoes demolishing buildings. All over our of volunteers, funders, and preservation professionals. Historic community – whether it is Forest Avenue, Willard preservation has been the very cornerstone of making this place Beach,T transportation corridors in Falmouth, so attractive as a place to live, work, and visit. or Westbrook’s mill structures – there is pres- Thank you again for making it possible for sure that is putting greater Portland’s historic Landmarks to continue to advocate that pre- character at risk. Our historic fabric is fragile. serving and reusing historic places is sustain- Once special places are destroyed or compro- able, enriches people’s lives, and brings diverse mised, there is no turning back the clock. communities together. Portland is undergoing one of its greatest Please join me in welcoming Sarah Hansen transformations since Urban Renewal in the as the new executive director of Greater 1960s and 70s. -

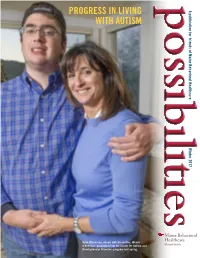

Progress in Living with Autism the O’Donovan Family Has Benefited from the Developmental Disorders Program

possibilities PROGRESS IN LIVING A publication for friends of Maine Behavioral Healthcare WITH AUTISM Winter 2017 Maine Behavioral Ryan O’Donovan, shown with his mother, Wendi Healthcare O’Donovan, graduated from the Center for Autism and MaineHealth 2 Developmental Disorders program last spring. A LETTER FROM STEPHEN MERZ IN THIS ISSUE Dear Friends: A LETTER FROM STEPHEN MERZ 2 Welcome to our new FAMILY HAS BENEFITED FROM THE DEVELOPMENTAL publication, Possibilities, DISORDERS PROGRAM 3 which is intended to provide you with useful information NEW INITIATIVE CONNECTS PATIENTS WITH CARE QUICKLY 5 about Maine Behavioral ROBYN OSTRANDER, MD, IS OPTIMISTIC ABOUT TREATING Healthcare (MBH) and CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS 6 showcase our progress in building a comprehensive system of behavioral LUNDER FAMILY ALLIANCE MAKES ALL THE DIFFERENCE 7 health services throughout Maine and eastern New Hampshire. A MESSAGE FROM THE DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE CHAIR 8 • In this inaugural issue, you will read about Ryan THANK YOU TO OUR 2016 DONORS 8 O’Donovan, a young man with autism who benefited from our outstanding Developmental SIGNS OF HOPE EVENT BENEFITS LUNDER FAMILY ALLIANCE 11 Disorders Program and whose family members responded with a gift that is appreciated by the program’s patients. • Another article features Robyn Ostrander, MD, the new Chair of the Glickman Center for Child & Ado- Maine Behavioral Healthcare lescent Psychiatry, who oversees the most compre- MaineHealth hensive array of treatment, training and research programs in youth psychiatry north of Boston. To learn more about Maine Behavioral Healthcare or to schedule a visit to • You’ll read how the Lunder Family Alliance at see the difference you make through your support of our mission, please Spring Harbor Hospital helped a young woman contact us. -

Bedrock Valleys of the New England Coast As Related to Fluctuations of Sea Level

Bedrock Valleys of the New England Coast as Related to Fluctuations of Sea Level By JOSEPH E. UPSON and CHARLES W. SPENCER SHORTER CONTRIBUTIONS TO GENERAL GEOLOGY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 454-M Depths to bedrock in coastal valleys of New England, and nature of sedimentary Jill resulting from sea-level fluctuations in Pleistocene and Recent time UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1964 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director The U.S. Geological Survey Library has cataloged this publication, as follows: Upson, Joseph Edwin, 1910- Bedrock valleys of the New England coast as related to fluctuations of sea level, by Joseph E. Upson and Charles W. Spencer. Washington, U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1964. iv, 42 p. illus., maps, diagrs., tables. 29 cm. (U.S. Geological Survey. Professional paper 454-M) Shorter contributions to general geology. Bibliography: p. 39-41. (Continued on next card) Upson, Joseph Edwin, 1910- Bedrock valleys of the New England coast as related to fluctuations of sea level. 1964. (Card 2) l.Geology, Stratigraphic Pleistocene. 2.Geology, Stratigraphic Recent. S.Geology New England. I.Spencer, Charles Winthrop, 1930-joint author. ILTitle. (Series) For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 CONTENTS Page Configuration and depth of bedrock valleys, etc. Con. Page Abstract.__________________________________________ Ml Buried valleys of the Boston area. _ _______________ -

Maine Historical Society

Preserving History • Engaging Minds • Connecting Maine MAINE HISTORICAL SOCIETY WINTER2015 Dear MHS Members and Friends It’s been a busy season at MHS, one marked by important programmatic initiatives, and by change. You have heard me talk about our ongoing ef- MAINE HISTORICAL SOCIETY forts to treat MHS as a “laboratory” through which we develop, pilot, and INCORPORATED 1822 test the ideas, activities, and programs that will guide the development of the institution. We’ve seen wonderful examples of that over the past six months that suggest the kind of organization we strive to be. This summer we hosted the Magna Carta exhibition in the Library’s 2nd floor reading room. The exhibition provided an opportunity to reflect both on our founding principles, and the OFFICERS work that remains to be done to achieve them. As part of our initiative, Danielle Conway, Preston R. Miller, Chair the new dean of the University of Maine School of Law, gave a remarkable talk that placed Joseph E. Gray, 1st Vice President Magna Carta in the context of her own life, her vision for the law school, and the responsi- Jean Gulliver, 2nd Vice President bilities that each of us share as Mainers and American citizens. Tyler Judkins, Secretary Carl L. Chatto, Treasurer The Baskets from the Dawnland exhibit demonstrates the principles and spirit that drive our MAINE HISTORICAL SOCIETY TRUSTEES work: how MHS can “be useful” (to quote annual meeting speaker Ellsworth Brown) and Richard E. Barnes Theodore L. Oldham use its resources to make history relevant and meaningful to contemporary Mainers. -

Coffin, Frank Morey, Shep Lee, Edmund S. Muskie and Don Nicoll Oral History Interview Chris Beam

Bates College SCARAB Edmund S. Muskie Oral History Collection Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library 8-6-1991 Coffin, Frank Morey, Shep Lee, Edmund S. Muskie and Don Nicoll oral history interview Chris Beam Follow this and additional works at: http://scarab.bates.edu/muskie_oh Recommended Citation Beam, Chris, "Coffin,r F ank Morey, Shep Lee, Edmund S. Muskie and Don Nicoll oral history interview" (1991). Edmund S. Muskie Oral History Collection. 92. http://scarab.bates.edu/muskie_oh/92 This Oral History is brought to you for free and open access by the Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Edmund S. Muskie Oral History Collection by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Interview with Edmund S. Muskie, Shep Lee, Don Nicoll and Frank Coffin by Chris Beam Summary Sheet and Transcript Interviewee Coffin, Frank Morey Lee, Shep Muskie, Edmund S., 1914-1996 Nicoll, Don Interviewer Beam, Chris Date August 6, 1991 Place Kennebunk, Maine ID Number MOH 022 Use Restrictions © Bates College. This transcript is provided for individual Research Purposes Only ; for all other uses, including publication, reproduction and quotation beyond fair use, permission must be obtained in writing from: The Edmund S. Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library, Bates College, 70 Campus Avenue, Lewiston, Maine 04240-6018. Biographical Note Frank Coffin Frank Morey Coffin was born in Lewiston, Maine on July 11, 1919. His parents were Ruth [Morey] and Herbert Coffin, who divorced when Frank was twelve. Ruth raised Frank alone on Wood St. -

Directions to the Friends of Casco Bay Office 43 Slocum Drive South Portland, Maine 04106 (207) 799-8574

Directions to the Friends of Casco Bay Office 43 Slocum Drive South Portland, Maine 04106 (207) 799-8574 Our office is on the campus of Southern Maine Community College (SMCC) near Spring Point Lighthouse. If using GPS, use SMCC’s address 2 Fort RD, South Portland, ME 04106. From I-95 & I-295 . Take the exit 45 toward I-295/US-1/ME-114/Maine Mall Rd/Payne Rd . Merge onto Maine Turnpike Approach . Take the exit onto I-295 N toward Portland . Take exit 4 toward Casco Bay Br/Portland/Waterfront . Continue onto Veterans Memorial Bridge . Continue onto Fore River Pkwy . Continue onto W Commercial St . Turn left to merge onto Casco Bay Bridge / Route 77 S . Continue onto Broadway (straight through the lights at the end of the bridge) . Follow Broadway all the way to its dead end at Benjamin W. Pickett Street (about 1.3 miles) . Turn right onto Benjamin W. Pickett Street . Take the 2nd left onto Slocum Drive (it looks like you’re entering a parking lot in front of a big dormitory; if you get to the stop sign at Fort Road, you missed Slocum) . Our office is a small one-story building at 43 Slocum, toward the end of the road on the left. Look for a small blue sign that reads “Friends of Casco Bay” in front of our building. From the South via Route 1 . Follow Route 1 N to South Portland . At the intersection with Broadway, turn right onto Broadway. Continue for 1.9 miles. Just past the fire station, turn right to stay on Broadway/77 S. -

National Register of Historic Places NATIONAL Registration Form REGISTER

NFS Form 10-900 QMS Mo. 1024-0018 (Ftav. 8-86) 1701 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service SEP 1 5 1983 National Register of Historic Places NATIONAL Registration Form REGISTER This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property historic name Eastern Promenade____________________________________________ other names/site number 2. Location street & number Bounded by E. Promenade, fasrn Ray, Fnrp> JNfll not for publication city, town Port! and M vicinity state code county code zip code Q41Q1 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property I I private I building(s) Contributing Noncontributing lx~l public-local district ____ ____ buildings I I public-State site . sites I I public-Federal structure . structures I object . objects 3 ? Total Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously ______N/A ___________ listed in the National Register 0_____ 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this [x] nomination EH request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60.