The Game of Thrones As a Teaching Tool: Enhancing Engagement and Student Learning Outcomes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GAME of THRONES® the Follow Tours Include Guides with Special Interest and a Passion for the Game of Thrones

GAME OF THRONES® The follow tours include guides with special interest and a passion for the Game of Thrones. However you can follow the route to explore the places featured in the series. Meet your Game of Thrones Tours Guide Adrian has been a tour guide for many years, with a passion for Game of Thrones®. During filming he was an extra in various scenes throughout the series, most noticeably, a stand in double for Ser Davos. He is also clearly seen guarding Littlefinger before his final demise at the hands of the Stark sisters in Winterfell. Adrian will be able to bring his passion alive through his experience, as well as his love of Northern Ireland. Cairncastle ~ The Neck & North of Winterfell 1 Photo stop of where Sansa learns of her marriage to Ramsay Bolton, and also where Ned beheads Will, the Night’s Watch deserter. Cairncastle Refreshment stop at Ballygally Castle, Ballygally Located on the scenic Antrim coast facing the soft, sandy beaches of Ballygally Bay. The Castle dates back to 1625 and is unique in that it is the only 17th Century building still used as a residence in Northern Ireland today. The hotel is reputedly haunted by a friendly ghost and brave guests can visit the ‘ghost room’ in one of the towers to see for themselves. View Door No. 9 of the Doors of Thrones and collect your first stamp in your Journey of Doors passport! In the hotel foyer you will be able to admire the display cabinets of the amazing Steensons Game of Thrones® inspired jewellery. -

GAME of THRONES Committee

2013 ALBERT CAMPBELL COLLEGIATE INSTITUTE MODEL UNITED NATIONS PRESENTS… GAME OF THRONES Committee Lead Chair: Ravena Rasalingam Chairs: Bharvjit Parmar and Adeel Malik Introduction Welcome delegates to the 2013 ACCI Model United Nations conference! Your head chairs for this committee will be Ravena Rasalingam and Bharvjit Parmar. This committee will be based on the book series, “A Song of Ice and Fire” and the HBO show, “Game of Thrones”. Disclaimer: Albert Campbell nor the chairs of this committee claim the proceeding as our original content; everything was invented by George R. R. Martin in his fantasy series, A Song of Ice and Fire. In this committee, the topics discussed will include the use of magic, sorcery, and the aid of supernatural creatures during wartime, the crisis involving the White Walkers, and the current economic state of Westeros. But be advised, this is a crisis committee. Please try to act in character and feel free to act in your own best interest. Plotting, scheming and clever use of personal relationships are encouraged! This council’s goals are to maintain peace and stability in Westeros, and to ensure the interests of the King. Good luck delegates, and remember- when you play the game of thrones, you either win or die. History: The Dawn Age (Prehistory- 1000) Westeros was initially inhabited by the Children of the Forest (a mysterious race of human-like creatures), giants and other mystical beings. The First men invaded Westeros in 1200 bringing weapons and bronze. The First men had larger numbers, were stronger, bigger, and more technologically advanced than the Children of the Forest and eventually established hundreds of small kingdoms throughout Westeros. -

The Many Faced Masculinities in a Game of Thrones Game of Thrones

DOI: 10.13114/MJH.2018.436 Tarihi: 17.08.2018 Mediterranean Journal of Humanities Kabul Tarihi: 28.11.2018 mjh.akdeniz.edu.tr Geliş VIII/2 (2018) 479-497 The Many Faced Masculinities in A Game of Thrones Game of Thrones’da Çok Yüzlü Erkeklik Türleri Cenk TAN ∗ Abstract: A Game of Thrones is a stunning medieval fantasy which tells the story of the immense struggle for power in an ancient world named ‘The Seven Kingdoms’. It was originally written as a series of novels by the American author George R. R. Martin in 1996 and adapted to the TV screen by HBO in 2011. The series has completed its sixth season and is scheduled to go on for a total of eight seasons. Since its first broadcast in 2011, A Game of Thrones has attracted millions of viewers on a global scale and has received a total of 38 Emmy Awards. In A Game of Thrones, gender is one of the central themes, as power relations generally evolve around different gender roles. This study analyses masculinity in A Game of Thrones and the different types of masculinities which are identified through various male and female characters. This classification places all of the characters in two distinct gender categories. It also reveals the impact of these diverse forms of masculinities on the lives of the main characters and the general storyline of the production. Thus, the paper deconstructs the constructed masculinities in A Game of Thrones by exposing their representation through the main characters. Keywords: A Game of Thrones, Masculinity, Raewyn Connell, Gender Roles, Cultural Studies Öz: A Game of Thrones, Yedi Krallık olarak adlandırılan antik bir dünyada iktidar mücadelesini anlatan eşsiz bir fantastik ortaçağ hikâyesidir. -

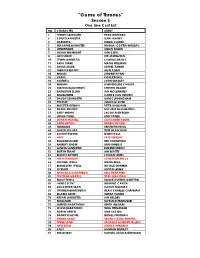

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO. CHARACTER ARTIST 1 TYRION LANNISTER PETER DINKLAGE 3 CERSEI LANNISTER LENA HEADEY 4 DAENERYS EMILIA CLARKE 5 SER JAIME LANNISTER NIKOLAJ COSTER-WALDAU 6 LITTLEFINGER AIDAN GILLEN 7 JORAH MORMONT IAIN GLEN 8 JON SNOW KIT HARINGTON 10 TYWIN LANNISTER CHARLES DANCE 11 ARYA STARK MAISIE WILLIAMS 13 SANSA STARK SOPHIE TURNER 15 THEON GREYJOY ALFIE ALLEN 16 BRONN JEROME FLYNN 18 VARYS CONLETH HILL 19 SAMWELL JOHN BRADLEY 20 BRIENNE GWENDOLINE CHRISTIE 22 STANNIS BARATHEON STEPHEN DILLANE 23 BARRISTAN SELMY IAN MCELHINNEY 24 MELISANDRE CARICE VAN HOUTEN 25 DAVOS SEAWORTH LIAM CUNNINGHAM 32 PYCELLE JULIAN GLOVER 33 MAESTER AEMON PETER VAUGHAN 36 ROOSE BOLTON MICHAEL McELHATTON 37 GREY WORM JACOB ANDERSON 41 LORAS TYRELL FINN JONES 42 DORAN MARTELL ALEXANDER SIDDIG 43 AREO HOTAH DEOBIA OPAREI 44 TORMUND KRISTOFER HIVJU 45 JAQEN H’GHAR TOM WLASCHIHA 46 ALLISER THORNE OWEN TEALE 47 WAIF FAYE MARSAY 48 DOLOROUS EDD BEN CROMPTON 50 RAMSAY SNOW IWAN RHEON 51 LANCEL LANNISTER EUGENE SIMON 52 MERYN TRANT IAN BEATTIE 53 MANCE RAYDER CIARAN HINDS 54 HIGH SPARROW JONATHAN PRYCE 56 OLENNA TYRELL DIANA RIGG 57 MARGAERY TYRELL NATALIE DORMER 59 QYBURN ANTON LESSER 60 MYRCELLA BARATHEON NELL TIGER FREE 61 TRYSTANE MARTELL TOBY SEBASTIAN 64 MACE TYRELL ROGER ASHTON-GRIFFITHS 65 JANOS SLYNT DOMINIC CARTER 66 SALLADHOR SAAN LUCIAN MSAMATI 67 TOMMEN BARATHEON DEAN-CHARLES CHAPMAN 68 ELLARIA SAND INDIRA VARMA 70 KEVAN LANNISTER IAN GELDER 71 MISSANDEI NATHALIE EMMANUEL 72 SHIREEN BARATHEON KERRY INGRAM 73 SELYSE -

Questions Are Coming. a Game of Thrones Quiz by Scott Hendrickson

Questions are coming. A Game of Thrones Quiz by Scott Hendrickson 1. What is the motto of House Stark? 2. What phrase do you use to tell a dragon to A) Winter is coming. breath fire? B) It's getting chilly. A) Dothraki. C) Burr, my feet are frozen. B) Dracarys. D) Seriously, do they ever heat this castle? C) Valar doharis. D) Light'em up, bitches! 3. Name Tywin Lannister’s three children. 4. Who are King Joffrey Baratheon’s real parents? ____________________, ____________________, & ____________________ & ____________________ ____________________ 5. What material is the weapon used by 6. Circle the locations that are in Westeros: Samuel Tarly to kill a white walker? Winterfell, Braavos, Dorne, Astapor, The Vale, ________________________________ Valyria, Volantis, King’s Landing, Asshai, Highgarden, Tacoma, Kirkland, 7. Hodor? 8. Who appointed Ned Stark as “Hand of the A) Hodor. King”? B) Hodor? A) Jon Arryn C) Hodor! B) Robert Baratheon D) Any of the above. C) Lord Varys D) Stannis Baratheon E) Tywin Lannister 9. Who initiated King Joffrey’s 10. Circle the names of the five non-bastard assassination? Stark children: A) Margery Tyrell B) Lady Olenna Tyrell Poliver, Sansa, Myrcella, Arya, Tommen, C) Petyr Baelish Rungsigul, Rickon, Robb, Ned, Cersei, Bran, D) Tyrion Lannister Rydon, Jon E) Sansa Stark F) Hodor 11. What are the names of Daenarys 12. What song starts playing before the Targaryan’s three dragons? murders occur at the Red Wedding? A) Dragol, Rhaelar and Viserya A) The Pride of the Lion B) Drogon, Rhaegal and Viserion B) The Bear and the Maiden Fair C) Drogo, Rhaegon and Viserios C) Ours is the fury D) Drogal, Rhaegar, and Viseron D) The Rains of Castamere E) Lucky, Dusty, and Ned E) "Shake it off" by Taylor Swift 13. -

Narrative Structure of a Song of Ice and Fire Creates a Fictional World

Narrative structure of A Song of Ice and Fire creates a fictional world with realistic measures of social complexity Thomas Gessey-Jonesa , Colm Connaughtonb,c , Robin Dunbard , Ralph Kennae,f,1 ,Padraig´ MacCarrong,h, Cathal O’Conchobhaire , and Joseph Yosee,f aFitzwilliam College, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB3 0DG, United Kingdom; bMathematics Institute, University of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7AL, United Kingdom; cLondon Mathematical Laboratory, London W6 8RH, United Kingdom; dDepartment of Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford, e f 4 Oxford OX2 6GG, United Kingdom; Centre for Fluid and Complex Systems, Coventry University, Coventry CV1 5FB, United Kingdom; L Collaboration, Institute for Condensed Matter Physics of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, 79011 Lviv, Ukraine; gMathematics Applications Consortium for Science and Industry, Department of Mathematics & Statistics, University of Limerick, Limerick V94 T9PX, Ireland; and hCentre for Social Issues Research, University of Limerick, Limerick V94 T9PX, Ireland Edited by Kenneth W. Wachter, University of California, Berkeley, CA, and approved September 15, 2020 (received for review April 6, 2020) Network science and data analytics are used to quantify static and Schklovsky and Propp (11) and developed by Metz, Chatman, dynamic structures in George R. R. Martin’s epic novels, A Song of Genette, and others (12–14). Ice and Fire, works noted for their scale and complexity. By track- Graph theory has been used to compare character networks ing the network of character interactions as the story unfolds, it to real social networks (15) in mythological (16), Shakespearean is found that structural properties remain approximately stable (17), and fictional literature (18). To investigate the success of Ice and comparable to real-world social networks. -

A Game of Thrones a Song of Ice and Fire by George R.R. Martin

A Game of Thrones A Song of Ice and Fire by George R.R. Martin Book One: A Game of Thrones Book Two: A Clash of Kings Book Three: A Storm of Swords Book Four: A Feast for Crows Book Five: A Dance with Dragons Book Six: The Winds of Winter (being written) Book Seven: A Dream of Spring “ Fire – Dragons, Targaryens Lord of Light Ice – Winter, Starks, the Wall White Walkers Spoilers!! Humans as meaning-makers – Jerome Bruner Humans as story-tellers – narrative theory Humans as mythopoeic–Carl G. Jung, Joseph Campbell The mythic themes in A Song of Ice and Fire are ancient Carl Jung: Archetypes are powerful & primordial images & symbols Collective unconscious Carl Jung’s archetypes Great Mother; Father; Hero; Savior… Joseph Campbell – The Power of Myth The Hero’s Journey Carole Pearson – the 12 archetypes Ego stage: Innocent; Orphan; Caretaker; Warrior Soul transformation: Seeker; Destroyer; Lover; Creator; Self: Ruler; Magician; Sage; Fool Maureen Murdock – The Heroine’s Journey The Great Mother (& Maiden, & Crone), the Great Father, the child, the Shadow, the wise old man, the trickster, the hero…. In the mystery of the cycle of seasons In ancient gods & goddesses In myth, fairy tale & fantasy & the Seven in A Game of Thrones The Gods: The Old Gods The Seven (Norse mythology): Maiden, Mother, Crone Father, Warrior, Smith Stranger (neither male or female) R’hilor (Lord of light) Others: The Drowned God, Mother Rhoyne The family sigils Stark - Direwolf Baratheon – Stag Lannister – Lion Targaryen -

Editor's Six Core Questions Game of Thrones

Editor’s Six Core Questions Game of Thrones - Season 2 What’s the Global Genre? For the Season: External: Society > Political Status > Admiration What is the Global Life Value? In this season we see power and impotence at higher stakes than ever. Whoever wins this battle will keep their power, and keep their head. Life and death are naturally in every beat, and on the scale of Action’s life and death we see everything from life to death to damnation. What are the objects of desire? Starks: To have justice restored and power shifted to the rightful heir Lannisters: To have power and get the throne Daenerys: To have power and get the throne What’s the controlling idea/theme? For the season: War lacks meaning and revolution fails when leaders are obsessed with the game of thrones and fail to address the real enemy (and using dishonourable methods) For the Lannisters: We gain power when we prove our ruthlessness, ingenuity and authority What are the Obligatory scenes of the Global Genre (Society) ● Inciting Attack - Robb Stark has numerous victories against Lanisters off-screen. He is a threat to the Lannisters ● Protagonists deny responsibility to respond - The Lannisters are the common enemy, but Renly, Stannis, Rob Stark, and the Greyjoys cannot unite under one banner ● Forced to respond, the protagonists lash out according to their positions on the power hierarchy - Stannis kills his brother through magic, Grayjoys raid the North, Robb Stark continues to win and keeps Jamie Lanister prisoner. ● Each Character learns what their antagonist’s object of desire is: ○ Rob wants to be acknowledged as King of the North and left alone ○ Stannis and Renly want to be King ○ Cersei, Tywin, and Tyrion want Joffrey to stay king ○ The warlocks want the dragons to get stronger magic ● Protagonists’ initial strategy to outmaneuver antagonists fails: Attempts to trade Jamie for the Stark girls fail because of his escape attempt causing friction between Catelyn and Karstarks. -

The Many Faced Masculinities in a Game of Thrones Game

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE DOI: 10.13114/MJH.2018.436 Tarihi: 17.08.2018 Mediterranean Journal of Humanities Kabul Tarihi: 28.11.2018 mjh.akdeniz.edu.tr Geliş VIII/2 (2018) 479-497 The Many Faced Masculinities in A Game of Thrones Game of Thrones’da Çok Yüzlü Erkeklik Türleri Cenk TAN ∗ Abstract: A Game of Thrones is a stunning medieval fantasy which tells the story of the immense struggle for power in an ancient world named ‘The Seven Kingdoms’. It was originally written as a series of novels by the American author George R. R. Martin in 1996 and adapted to the TV screen by HBO in 2011. The series has completed its sixth season and is scheduled to go on for a total of eight seasons. Since its first broadcast in 2011, A Game of Thrones has attracted millions of viewers on a global scale and has received a total of 38 Emmy Awards. In A Game of Thrones, gender is one of the central themes, as power relations generally evolve around different gender roles. This study analyses masculinity in A Game of Thrones and the different types of masculinities which are identified through various male and female characters. This classification places all of the characters in two distinct gender categories. It also reveals the impact of these diverse forms of masculinities on the lives of the main characters and the general storyline of the production. Thus, the paper deconstructs the constructed masculinities in A Game of Thrones by exposing their representation through the main characters. -

Final Draft Thesis Corrected

REDEFINING MASCULINITY IN GAME OF THRONES !1 Redefining Masculinity through Disability in HBO’s Game of Thrones A Capstone Thesis Submitted to Southern Utah University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Professional Communication April 2016 By Amanda J. Dearman Capstone Committee: Dr. Kevin A. Stein, Ph.D., Chair Dr. Arthur Challis, Ed.D. Dr. Matthew H. Barton, Ph.D. Running head: REDEFINING MASCULINITY IN GAME OF THRONES !3 Acknowledgements I have been blessed with the support of a number of number of people, all of whom I wish to extend my gratitude. The completion of my Master’s degree is an important milestone in my academic career, and I could not have finished this process without the encouragement and faith of those I looked toward for support. Dr. Kevin Stein, I can’t thank you enough for your commitment as not only my thesis chair, but as a professor and colleague who inspired many of my creative endeavors. Under your guidance I discovered my love for popular culture studies and, as a result, my voice in critical scholarship. Dr. Art Challis and Dr. Matthew Barton, thank you both for lending your insight and time to my committee. I greatly appreciate your guidance in both the completion of my Master’s degree and the start of my future academic career. Your support has been invaluable. Thank you. To my family and friends, thank you for your endless love and encouragement. Whether it was reading my drafts or listening to me endlessly ramble on about my theories, your dedication and participation in this accomplishment is equal to that of my own. -

Game of Thrones Background Guide Table of Contents

Game of Thrones Background Guide Table of Contents Letter from the Chair Letter from the Crisis Director Committee Logistics Introduction to the Committee Introduction to House Stark Introduction to House Lannister Introduction to House Targaryen Questions to Consider Resources to Use Resources Used Dossiers Appendix Staff of the Committee Chair Azanta Thakur Vice Chair Victoria Lopez Crisis Director Sam Lyons Assistant Crisis Director Ariana Thorpe Under Secretary General Jane Gallagher Taylor Cowser, Secretary General Neha Iyer, Director General Letter from the Chair Dear Delegates, On behalf of our committee, I want to extend a warm welcome to you all to BosMUN XIX. I am so excited that you will be a part of this committee and I expect us all to have a dramatic — yet fantastic — weekend. We have a lot of exciting things in store, so get ready, binge the show, and bring your game face. My name is Azanta Thakur and I will be your Chair for the conference weekend. I’m a senior at Boston University studying Public Health and Environmental Analysis & Policy. This is my fourth BosMUN and I’m really looking forward to my final MUN conference. I’ve held every role in BosMUN; from the Secretariat, to the Dais, to the Crisis Room — I hold this conference very near and dear to my heart. For me, doing my last committee on the greatest TV show of all time was the perfect way to go out with a bang. You have been given the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to conclude this series the way you want. -

GOCASK Government Cabinet of the Seven Kingdoms Topic: “The True Heir of the Seven Kingdoms Dear Delegate: I Have the Pleasure

GOCASK Government Cabinet of the Seven Kingdoms Topic: “The True Heir of the Seven Kingdoms Dear delegate: I have the pleasure of welcoming you to ULSACUNMUN 2020. My name is Kaory Rios and I am honored of being the president and creator of this year´s new committee GOCASK (government Cabinet of the Seven Kingdoms) based on The Game of Thrones series. I'm eager to get to know you, and make the best out of this Model of the United Nations. First of all I would like to tell you a little bit about myself. I´m 18 years old and also a senior in highschool. I enjoy hanging out with my friends, taking pictures, learning new languages, travelling, watching movies, among many other things. My plan is to study film in Puebla and become a director. This is my 5th MUN conference and my third as part of the chair. If there is something I know for sure is that MUN has helped me grow as a person by giving me leadership skills, and the opportunity of having a word that actually matters in world wide problems in order to find the best solution. This topic is more than exciting for me, and hopefully you´ll find the same way. I expect your utmost performance and for you to give your nonpareil effort that is needed for this committee. Remember to be confident with what you say, if you prepared well there is no reason to be nervous. I wish you the best of lucks and I hope this conference to be a remarkable experience for everyone.