Lady Lawyers: Not an Oxymoron

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Note: All Results Are for Rogers County

Note: All results are for Rogers County. Some numbers may be pre-provisional and may be off by a few votes, but do not affect the overall results in any significant way. Source: Rogers County Election Board Archive 1994 Election Cycle Voter Turnout for Special Election for County Question – February 9, 1993 6,616 Voted/41,639 Registered = 15.89% County Question Approving the Extension of a 1% Sales Tax for the Maintenance and Construction of County Roads until 1998 – February 9, 1993 Yes No 4,531 2,048 Voter Turnout for Special Election for SQ No. 659 – February 8, 1994 3,762 Voted/36,404 Registered = 10.33% SQ No. 659: Makes Local School Millage Levies Permanent until Repealed by Voters– February 8, 1994 Yes No 2,295 1,330 Voter Turnout for Special Election for SQ No. 658 – May 10, 1994 12,566 Voted/36,754 Registered = 34.19% SQ No. 658: Approval of a State Lottery with Specifics on How Funds Would Be Controlled – May 10, 1994 Yes No 5,291 7,272 Voter Turnout for Democratic Primary Election – August 23, 1994 7,678 Voted/23,936 Registered = 32.08% Oklahoma Gubernatorial Democratic Primary Results – August 23, 1994 Jack Mildren Danny Williams Bernice Shedrick Joe Vickers 3,284 646 3,312 305 Oklahoma Lieutenant Gubernatorial Democratic Primary Results – August 23, 1994 Dave McBride Walt Roberts Nance Diamond Bob Cullison 1,130 426 2,685 3,183 Oklahoma State Auditor and Inspector Democratic Primary Results – August 23, 1994 Clifton H. Scott Allen Greeson 4,989 1,956 Oklahoma Attorney General Democratic Primary Results – August 23, 1994 John B. -

Ally, the Okla- Homa Story, (University of Oklahoma Press 1978), and Oklahoma: a History of Five Centuries (University of Oklahoma Press 1989)

Oklahoma History 750 The following information was excerpted from the work of Arrell Morgan Gibson, specifically, The Okla- homa Story, (University of Oklahoma Press 1978), and Oklahoma: A History of Five Centuries (University of Oklahoma Press 1989). Oklahoma: A History of the Sooner State (University of Oklahoma Press 1964) by Edwin C. McReynolds was also used, along with Muriel Wright’s A Guide to the Indian Tribes of Oklahoma (University of Oklahoma Press 1951), and Don G. Wyckoff’s Oklahoma Archeology: A 1981 Perspective (Uni- versity of Oklahoma, Archeological Survey 1981). • Additional information was provided by Jenk Jones Jr., Tulsa • David Hampton, Tulsa • Office of Archives and Records, Oklahoma Department of Librar- ies • Oklahoma Historical Society. Guide to Oklahoma Museums by David C. Hunt (University of Oklahoma Press, 1981) was used as a reference. 751 A Brief History of Oklahoma The Prehistoric Age Substantial evidence exists to demonstrate the first people were in Oklahoma approximately 11,000 years ago and more than 550 generations of Native Americans have lived here. More than 10,000 prehistoric sites are recorded for the state, and they are estimated to represent about 10 percent of the actual number, according to archaeologist Don G. Wyckoff. Some of these sites pertain to the lives of Oklahoma’s original settlers—the Wichita and Caddo, and perhaps such relative latecomers as the Kiowa Apache, Osage, Kiowa, and Comanche. All of these sites comprise an invaluable resource for learning about Oklahoma’s remarkable and diverse The Clovis people lived Native American heritage. in Oklahoma at the Given the distribution and ages of studies sites, Okla- homa was widely inhabited during prehistory. -

Oklahoma Agencies, Boards, and Commissions

ABC Oklahoma Agencies, Boards, and Commissions Elected Officers, Cabinet, Legislature, High Courts, and Institutions As of September 10, 2018 Acknowledgements The Oklahoma Department of Libraries, Office of Public Information, acknowledges the assistance of the Law and Legislative Reference staff, the Oklahoma Publications Clearing- house, and staff members of the agencies, boards, commissions, and other entities listed. Susan McVey, Director Connie G. Armstrong, Editor Oklahoma Department of Libraries Office of Public Information William R. Young, Administrator Office of Public Information For information about the ABC publication, please contact: Oklahoma Department of Libraries Office of Public Information 200 NE 18 Street, Oklahoma City, OK 73105–3205 405/522–3383 • 800/522–8116 • FAX 405/525–7804 libraries.ok.gov iii Contents Executive Branch 1 Governor Mary Fallin ............................................3 Oklahoma Elected Officials ......................................4 Governor Fallin’s Cabinet. 14 Legislative Branch 27 Oklahoma State Senate ....................................... 29 Senate Leadership ................................................................ 29 State Senators by District .......................................................... 29 Senators Contact Reference List ................................................... 30 Oklahoma State House of Representatives ..................... 31 House of Representatives Leadership .............................................. 31 State Representatives by District -

Oklahoma Women

Oklahomafootloose andWomen: fancy–free Newspapers for this educational program provided by: 1 Oklahoma Women: Footloose and Fancy-Free is an educational supplement produced by the Women’s Archives at Oklahoma State University, the Oklahoma Commission on the Status of Women and The Oklahoman. R. Darcy Jennifer Paustenbaugh Kate Blalack With assistance from: Table of Contents Regina Goodwin Kelly Morris Oklahoma Women: Footloose and Fancy-Free 2 Jordan Ross Women in Politics 4 T. J. Smith Women in Sports 6 And special thanks to: Women Leading the Fight for Civil and Women’s Rights 8 Trixy Barnes Women in the Arts 10 Jamie Fullerton Women Promoting Civic and Educational Causes 12 Amy Mitchell Women Take to the Skies 14 John Gullo Jean Warner National Women’s History Project Oklahoma Heritage Association Oklahoma Historical Society Artist Kate Blalack created the original Oklahoma Women: watercolor used for the cover. Oklahoma, Foot-Loose and Fancy Free is the title of Footloose and Fancy-Free Oklahoma historian Angie Debo’s 1949 book about the Sooner State. It was one of the Oklahoma women are exciting, their accomplishments inspirations for this 2008 fascinating. They do not easily fi t into molds crafted by Women’s History Month supplement. For more on others, elsewhere. Oklahoma women make their own Angie Debo, see page 8. way. Some stay at home quietly contributing to their families and communities. Some exceed every expectation Content for this and become fi rsts in politics and government, excel as supplement was athletes, entertainers and artists. Others go on to fl ourish developed from: in New York, California, Japan, Europe, wherever their The Oklahoma Women’s fancy takes them. -

Opening a Law Office on a Budget These Products

Volume 83 u No. 26 u Oct. 6, 2012 ALSO INSIDE • Annual Meeting • Lambird Award Winners • New Lawyers Admitted 720.932.8135 Vol. 83 — No. 26 — 10/6/2012 The Oklahoma Bar Journal 2057 At the end of the day... Who’s Really Watching Your Firm’s 401(k)? And, what is it costing you? YES NO Does your firm’s 401(k) feature no out-of-pocket fees? Does your firm’s 401(k) include professional investment fiduciary services? Is your firm’s 401(k) subject to quarterly reviews by an independent board of directors? If you answered no to any of these questions, contact the ABA Retirement Funds Program by phone (866) 812-1510, on the web at www.abaretirement.com or by email [email protected] to learn how we keep a close watch over your 401(k). Please visit the ABA Retirement Funds Booth at the upcoming Oklahoma Bar Association Annual Meeting for a free cost comparison and plan evaluation. November 14-16, 2012 • Sheraton Hotel, Oklahoma City Who’s Watching Your Firm’s 401(k)? The American Bar Association Members/Northern Trust Collective Trust (the “Collective Trust”) has filed a registration statement (including the prospectus therein (the “Prospectus”)) with the Securities and Exchange Commission for the offering of Units representing pro rata beneficial interests in the collective investment funds established under the Collective Trust. The Collective Trust is a retirement program sponsored by the ABA Retirement Funds in which lawyers and law firms who are members or associates of the American Bar Association, most state and local bar associations and their employees and employees of certain organizations related to the practice of law are eligible to participate. -

Oklahoma WOMEN's HAIL of FAME

OKlAHOMA WOMEN'S HAIL OF FAME he Oklahoma Women's Hall of Fame, created in 1982, is a project ofthe T Oklahoma Commission on the Status ofWomen. Inductees are women who have lived in Oklahoma for a major portion of their lives or who are easily identified as Oklahomans and are: pioneers in their field or in a project that benefits Oklahoma, have made a significant contribution to the State of Oklahoma, serve or have served as role models to other Oklahoma women, are "unsung heroes" who have made a difference in the lives of Oklahomans or Americans because of their actions, have championed other women, women's issues, or served as public policy advocates for issues important to women. Inductees exemplifY the Oklahoma Spirit. Since 2001, the awards have been presented in odd numbered years during "Women's History Month" in March. A call for nominations takes place during the late summer of the preceding year. *inducted posthumously 1982 Hannah Diggs Atkins Oklahoma City State Representative, U.N. Ambassador Photo courtesy of' Oklahoma State University Library 158 Notable Women/Women's Hall ofFame 1982 Kate Barnard* Oklahoma City Charities & Corrections Commissioner, Social Reform Advocate Photo courtesy ofOklahoma Historical Society 1982 June Brooks Ardmore Educator, Oil and Gas Executive Photo copyright, The Oklahoma Publishing Company 1982 Gloria Stewart Farley Heavener Local Historian Photo provided Oklahoma Women's Almanac 159 1982 Aloysius Larch-Miller* Oklahoma City Woman Suffrage Leader Photo copyright, The Oklahoma Publishing Company 1982 Susie Peters Anadarko Founder Kiowa Indian School of Art Photo courtesy of Oklahoma Historical Society 1982 Christine Salmon Stillwater Educator, Mayor, Community Volunteer Photo courtesy ofSheerar Museum, Stillwater, OK 160 Notable Women/Women's Hall of Fame 1982 Edyth Thomas Wallace Oklahoma City Journalist Photo copyright, The Oklahoma Publishing Company 1983 Zelia N. -

Schell Amended Complaint

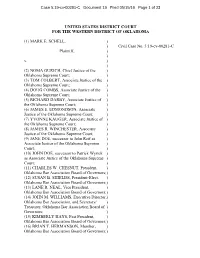

Case 5:19-cv-00281-C Document 19 Filed 05/15/19 Page 1 of 23 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF OKLAHOMA (1) MARK E. SCHELL, ) ) Civil Case No. 5:19-cv-00281-C Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) ) (2) NOMA GURICH, Chief Justice of the ) Oklahoma Supreme Court; ) (3) TOM COLBERT, Associate Justice of the ) Oklahoma Supreme Court; ) (4) DOUG COMBS, Associate Justice of the ) Oklahoma Supreme Court; ) (5) RICHARD DARBY, Associate Justice of ) the Oklahoma Supreme Court; ) (6) JAMES E. EDMONDSON, Associate ) Justice of the Oklahoma Supreme Court; ) (7) YVONNE KAUGER, Associate Justice of ) the Oklahoma Supreme Court; ) (8) JAMES R. WINCHESTER, Associate ) Justice of the Oklahoma Supreme Court; ) (9) JANE DOE, successor to John Reif as ) Associate Justice of the Oklahoma Supreme ) Court; ) (10) JOHN DOE, successor to Patrick Wyrick ) as Associate Justice of the Oklahoma Supreme ) Court; ) (11) CHARLES W. CHESNUT, President, ) Oklahoma Bar Association Board of Governors; ) (12) SUSAN B. SHIELDS, President-Elect, ) Oklahoma Bar Association Board of Governors; ) (13) LANE R. NEAL, Vice President, ) Oklahoma Bar Association Board of Governors; ) (14) JOHN M. WILLIAMS, Executive Director,) Oklahoma Bar Association, and Secretary/ ) Treasurer, Oklahoma Bar Association Board of ) Governors; ) (15) KIMBERLY HAYS, Past President, ) Oklahoma Bar Association Board of Governors; ) (16) BRIAN T. HERMANSON, Member, ) Oklahoma Bar Association Board of Governors; ) Case 5:19-cv-00281-C Document 19 Filed 05/15/19 Page 2 of 23 (17) MARK E. FIELDS, Member, Oklahoma ) Bar Association Board of Governors; ) (18) DAVID T. MCKENZIE, Member, ) Oklahoma Bar Association Board of Governors; ) (19) TIMOTHY E. DECLERCK, Member ) Oklahoma Bar Association Board of Governors; ) (20) ANDREW E. -

Couch, Hon. Valerie

Judicial Profile MELANIE JESTER Hon. Valerie Couch U.S. Magistrate Judge, Western District of Oklahoma “HAVE PATIENCE”—A simple expression of profound Everything that Judge Couch does, she does with deep thought, thoroughness, and attention to detail. wisdom. Judge Valerie Couch is a jurist of pa- She does nothing halfway. Whether her task is to tience, persistence, and grace, who is also keen- review a pro se litigant’s pleadings, prepare a CLE presentation, lead a committee meeting, or mentor a ly perceptive and intuitive. She has an extraor- young lawyer, Judge Couch gives full attention to the dinarily sharp mind that can cut through the matter at hand. Her work is always reflective of the precision of her thinking and the care she takes in deepest of legally mired arguments and reduce rendering her rulings and opinions. the issues to their simplest form. She knows the That quality of precision—especially when it comes to language—can be traced to her literary education. questions to ask, probes at just the right times, Judge Couch graduated from the University of Califor- nia at Los Angeles in 1974 with a B.A. in English and and waits for the litigants to respond. then pursued a master’s degree in English literature at the University of Oklahoma, which she earned in 1978. Her appreciation for literature and for language is an asset in crafting her judicial opinions. She is mindful of the nuances in word choice when recount- ing the factual record, analyzing statutory provisions, or applying standards of review. Her love of literature continues to this day. -

See the Alumni Magazine, Page 10 for More Information

F O C U S FALL 2016 ALUMNI MAGAZINE of OKLAHOMA CITY UNIVERSITY OKCU.EDU HONOR ROLL PRIMARY CARE PGA CARDED In appreciation of the generosity New Physician Assistant program nurtures Alumnus earns three pro golf victories, of our donors, who enable excellence. students’ lofty aspirations. looks for fourth PGA TOUR berth. Economics Enterprise Institute Provides ‘Data-Driven Insight’ for Clients, Windfall Experience for Students CONTENTS Robert Henry, President Kent Buchanan, Interim Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs ADMINISTRATIVE CABINET Jim Abbott, Assistant Vice President of Intercollegiate Athletics Amy Ayres, Vice President for Student Affairs and Dean of Students Leslie Berger, BA ’02, Senior Director of University Communications Joey Croslin, Chief Human Resources Officer David Steffens, Acting Assistant Provost Gerry Hunt, Chief Information Officer Catherine Maninger, Chief Financial Officer Charles Neff, BA ’99, MBA ’11, Vice President for University-Church Relations Marty O’Gwynn, Vice President for University Advancement and External Relations Casey Ross-Petherick, BSB ’00, MBA/JD ’03, General Counsel Kevin Windholz, Vice President for Enrollment Management ALUMNI RELATIONS Cary Pirrong, BS ’87, JD ’90, Director of Alumni Relations Chris Black, BME ’00, MBA ’10, President, Alumni Board EDITORIAL STAFF Leslie Berger, BA ’02, Senior Director of University Communications ON THE COVER Rod Jones, MBA ’12, Editor of FOCUS and Associate Director of Public Relations Kim Mizar, Communications Coordinator ALL THINGS ANALYZED -

OBA Award History

Oklahoma Bar Association Award History Able, Edwin D. – Oklahoma City 1985 Earl Sneed Award Adair County Bar Association 1999 Outstanding County Bar Association Award Adair, Susan G. – Norman 1992 Award for Outstanding Pro Bono Service Adams, Charles W. – Tulsa 2000 Distinguished Service Award 1983 Golden Gavel Award Adkins, Christen V. 1997 Outstanding Law School Student Award – OCU Advertising Rules Special Committee 1982 Golden Gavel Award 1980 Golden Gavel Award – David Swank, chair Aids Victim Support Committee (OBA/Young Lawyers Division) 1993 Golden Gavel Award, Michael M. Sykes, chair Ailles Bahm, Angela – Oklahoma City 2017 President’s Award Albert, Vic 1986 Outstanding Law School Student Award – OCU Alma Wilson Award 2018 Sharon Wigdor Byers, Edmond 2017 Carolyn Thompson, Edmond 2016 Brad Davenport, Oklahoma City 2015 Christine Batson Deason, Edmond 2014 Don Smitherman, Oklahoma City 2013 Ben Loring, Miami 2012 Frederic Dorwart, Tulsa 2011 Robert N. Sheets, Oklahoma City 2010 Judge C. William Stratton, Lawton 2009 Judge Donald Deason, Oklahoma City 2008 Renee DeMoss, Tulsa 2008 Judge Richard A. Woolery, Sapulpa 2007 Denny Johnson, Tulsa 2006 Judge Doris Fransein, Tulsa 2006 Michael Loeffler, Bristow 2005 Judge Daman Cantrell, Tulsa 2004 Judge Candace Blalock, Pauls Valley 2004 Judge Deborah Shallcross, Tulsa 2003 Judge Alan J. Couch, Norman (award posthumously) 2002 Judge Gary E. Miller, Yukon 2001 Anne B. Sublett, Tulsa 2000 Norma Eagleton, Tulsa Argo, Judge Doyle – Oklahoma City 2008 Award of Judicial Excellence Armor, G.W. “Bill” – Laverne 1995 Award for Outstanding Pro Bono Service Arrington, John L. Jr. – Tulsa 1995 Masonic Award for Ethics 1991 President’s Award – given by R. -

Oklahoma City University Law Review

OCULREV Vol. 41-3 Winter 2016 Burke 337--423 (Do Not Delete) 4/28/2017 2:00 PM OKLAHOMA CITY UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 41 WINTER 2016 NUMBER 3 ARTICLE THE EVOLUTION OF WORKERS’ COMPENSATION LAW IN OKLAHOMA: IS THE GRAND BARGAIN STILL ALIVE? Bob Burke I. INTRODUCTION The concept of compensating injured workers for work-related accidents is not new. As early as 2050 B.C., the law of the city-state of Ur in the Fertile Crescent provided for payment for injuries to specific parts of the body.1 “Ancient Greek, Roman, Arab, and Chinese law” allowed a J.D., Oklahoma City University School of Law; B.A., Journalism, University of Oklahoma; Honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters, Oklahoma City University; Fellow, The College of Workers’ Compensation Lawyers; assisted in writing changes to Oklahoma workers’ compensation law, 1977 to 2011; rewrote entire Workers’ Compensation Code, 2011; member, Oklahoma Advisory Council on Workers’ Compensation, 1994 to 2011; Oklahoma Secretary of Commerce in administration of Governor David Boren; managed Boren’s first campaign for U.S. Senate, 1978; chair, Legal Committee, Fallin Commission for Workers’ Compensation Reform, 1994 to 1998; member, Oklahoma Bar Association Judicial Elections Committee, 2016; represented 16,000 injured workers since 1980. All conclusions are those of the author. 1. Gregory P. Guyton, A Brief History of Workers’ Compensation, 19 IOWA ORTHOPAEDIC J., 1999, at 106, 106 (1999). Guyton, a board-certified orthopedic surgeon, authored an excellent overview of the workers’ compensation system in the United States 337 OCULREV Vol. 41-3 Winter 2016 Burke 337--423 (Do Not Delete) 4/28/2017 2:00 PM 338 Oklahoma City University Law Review [Vol. -

Black Legal History in Oklahoma

ALSO INSIDE: OBA & Diversity Awards • New Members Admitted • JNC Elections Legislative Update • New Member Benefit • Solo & Small Firm Conference Volume 92 — No. 5 — May 2021 Black Legal History in Oklahoma contents May 2021 • Vol. 92 • No. 5 THEME: BLACK LEGAL HISTORY IN OKLAHOMA Editor: Melissa DeLacerda Cover Art: Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher by Mitsuno Reedy from the Oklahoma State Capitol Art Collection, used with permission, courtesy of the Oklahoma Arts Council FEATURES PLUS 6 Blazing the Trail: Oklahoma Pioneer African 36 OBA Awards: Leading is a Choice, American Attorneys Let Us Honor It BY JOHN G. BROWNING BY KARA I. SMITH 12 ‘As Soon As’ Three Simple Words That Crumbled 39 New Member Benefit: OBA Newsstand Graduate School Segregation: ADA LOis SipUEL V. 40 Celebrate Diversity With an Award BOARD OF REGENTS Nomination BY CHERYL BROWN WATTLEY 42 New Lawyers Take Oath in Admissions 18 GUINN V. U.S.: States’ Rights and the 15th Amendment Ceremony BY ANTHONY HENDRicks 44 Legislative Monitoring Committee Report: 24 The Tulsa Race Massacre: Echoes of 1921 Felt a Session Winding Down Century Later BY MILES PRINGLE BY JOHN G. BROWNING 45 Solo & Small Firm Conference 30 Oklahoma’s Embrace of the White Racial Identity BY DANNE L. JOHNSON AND PAMELA JUAREZ 46 Judicial Nominating Commission Elections DEPARTMENTS 4 From the President 50 From the Executive Director 52 Law Practice Tips 58 Ethics & Professional Responsibility 60 Board of Governors Actions 64 Oklahoma Bar Foundation News 68 Young Lawyers Division 73 For Your Information 74 Bench and Bar Briefs 80 In Memoriam 82 Editorial Calendar 88 The Back Page PAGES 36 and 40 – PAGE 42 – OBA & Diversity Awards New Lawyers Take Oath FROM THE PRESIDENT Words, Life of Frederick Douglass Are Inspiring By Mike Mordy HE THEME OF THIS BAR JOURNAL, “BLACK who was known as a “slave breaker,” and I TLegal History,” reminded me of Frederick Douglass, have read he beat Douglass so regularly that who was not an attorney but had all the attributes his wounds did not heal between beatings.