Download This Article in PDF Format

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Experimental Study of Municipal Solid Waste (Msw) Landfills and Non- Authorized Waste Damps Impact on the Environment

Linnaeus ECO-TECH ´10 Kalmar, Sweden, November 22-24, 2010 EXPERIMENTAL STUDY OF MUNICIPAL SOLID WASTE (MSW) LANDFILLS AND NON- AUTHORIZED WASTE DAMPS IMPACT ON THE ENVIRONMENT Veronica Tarbaeva Dmitry Delarov Committee on Natural Resources of Leningrad region, Russia ABSTRACT A purpose was an analysis of waste disposal sites existing in the Leningrad region and a choice of facilities potentially suitable for the removal and utilization of greenhouse- and other gases. In order to achieve the purpose in view, data were collected on the arrangement of non-authorized landfills and waste dumps within the Leningrad region. The preliminary visual evaluation and instrumental monitoring were carried out for 10 facilities. The evaluation of greenhouse- and other gas emissions into the atmosphere as well as of ground water pollution near places of waste disposal was performed. A databank was created for waste disposal sites where it could be possible to organize the work on removing and utilizing of greenhouse gas. The conducted examination stated that landfills exert negative influence on the environment in the form of emissions into the atmosphere and impurities penetrating underground and surface water. A volume of greenhouse gas emissions calculated in units of СО2 – equivalent from different projects fluctuates from 63.8 to 8091.4 t in units of СО2 – equivalent. Maximum summarized emissions of greenhouse gases in units of СО2 – equivalent were stated for MSW landfills of the towns of Kirishi, Novaya Ladoga and Slantsy, as well as for MSW landfills near Lepsari residential settlement and the town of Vyborg. KEYWORDS Non-authorized waste dumps, MSW landfills, greenhouse gases, atmospheric air pollution, instrumental monitoring. -

«Hermitage» - First E-Navigation Testbed in Russia

«Hermitage» - first e-Navigation testbed in Russia Andrey Rodionov CEO of “Kronstadt Technologies” (JSC) "Kronstadt Group“ (St. Petersburg, Russia) About «Kronstadt Technologies» (JSC) 2 . «Kronstadt Technologies» (Included in the Kronstadt Group) is a national leader in the field of digital technologies for marine and river transport. Kronstadt Group (until 2015 - part of Transas Group) has been operating in this market for more than 25 years. Now we are part of the largest Russian financial corporation – «SISTEMA» (SYSTEM) . We are the only Russian technology company to become a member in IALA association, which is operation agency for IMO in terms of development and implementation of e-Navigation. «Kronstadt Technologies» is a contractor for developing business road map MARINET by the order of National Technology Initiative of Russia. The company takes part in developing of business road map for improvement of regulation of Russian Federation in terms of e-Navigation and USV. The second stage of development Testbed “Hermitage” 3 . In 2016 we started creating the first testbed e-Navigation in Russia. Now the second stage of the testbed's development is taking place. This work is performed by the Kronstadt Group in cooperation with our partners. Customers - Ministry of Transport of Russia and MariNet (from National Technological Initiative). Research and development (R&D) names: “e-Sea” and “e-NAV”. Implementation period – 2016-2021. The name of testbed - "Hermitage" (in honor of the famous museum in St. Petersburg). The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia . Testbed includes the sea and the river segments. Borders of Testbed “Hermitage” in Russia 4 Implementing e-Navigation in Russia 5 The ways of implementing e-Navigation in Russia Federal target program "GLONASS" State program "National Technology Initiative" Ministry of Transport Program "MariNet" 2016 R&D "e-Sea" R&D "e-NAV" 2018 Previous experience of Kronstadt Group in the technology e-Navigation : • R&D "Approach-T“ in 2009, • R&D "Approach-Nav-T“ in 2012. -

Report to the Russian Government on the Visit to the Russian Federation

CPT/Inf (2013) 41 Report to the Russian Government on the visit to the Russian Federation carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 21 May to 4 June 2012 The Russian Government has requested the publication of this report and of its response. The Government’s response is set out in document CPT/Inf (2013) 42. Strasbourg, 17 December 2013 - 3 - CONTENTS Copy of the letter transmitting the CPT's report............................................................................ 5 I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 7 A. Dates of the visit and composition of the delegation .............................................................. 7 B. Establishments visited .............................................................................................................. 8 C. Consultations held by the delegation and co-operation received ......................................... 9 D. Urgent action requested ......................................................................................................... 12 E. Monitoring of places of deprivation of liberty ..................................................................... 13 II. FACTS FOUND DURING THE VISIT AND ACTION PROPOSED .............................. 15 A. Persons held by the police or other law enforcement agencies ........................................... 15 1. Preliminary remarks ....................................................................................................... -

Cahiers Du Monde Russe, 56\/4

Cahiers du monde russe Russie - Empire russe - Union soviétique et États indépendants 56/4 | 2015 Médiateurs d'empire en Asie centrale (1820-1928) Repression of Kazakh Intellectuals as a Sign of Weakness of Russian Imperial Rule The paradoxical impact of Governor A.N. Troinitskii on the Kazakh national movement* La répression des intellectuels kazakhs ou la faiblesse de l’administration directe russe : l’impact paradoxal du gouverneur A.N. Trojnickij sur le mouvement national kazakh Tomohiko Uyama Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/monderusse/8216 DOI: 10.4000/monderusse.8216 ISSN: 1777-5388 Publisher Éditions de l’EHESS Printed version Date of publication: 1 October 2015 Number of pages: 681-703 ISBN: 978-2-7132-2507-9 ISSN: 1252-6576 Electronic reference Tomohiko Uyama, « Repression of Kazakh Intellectuals as a Sign of Weakness of Russian Imperial Rule », Cahiers du monde russe [Online], 56/4 | 2015, Online since 01 October 2018, Connection on 24 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/monderusse/8216 ; DOI : 10.4000/monderusse.8216 This text was automatically generated on 24 April 2019. © École des hautes études en sciences sociales Repression of Kazakh Intellectuals as a Sign of Weakness of Russian Imperial ... 1 Repression of Kazakh Intellectuals as a Sign of Weakness of Russian Imperial Rule The paradoxical impact of Governor A.N. Troinitskii on the Kazakh national movement* La répression des intellectuels kazakhs ou la faiblesse de l’administration directe russe : l’impact paradoxal du gouverneur A.N. Trojnickij sur le mouvement national kazakh Tomohiko Uyama 1 Although bureaucracy as an ideal type in Max Weber’s concept is a form of impersonal rule, the personality of individual bureaucrats often influences the actual handling of administrative matters. -

Federal Research Division Country Profile: Tajikistan, January 2007

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Tajikistan, January 2007 COUNTRY PROFILE: TAJIKISTAN January 2007 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of Tajikistan (Jumhurii Tojikiston). Short Form: Tajikistan. Term for Citizen(s): Tajikistani(s). Capital: Dushanbe. Other Major Cities: Istravshan, Khujand, Kulob, and Qurghonteppa. Independence: The official date of independence is September 9, 1991, the date on which Tajikistan withdrew from the Soviet Union. Public Holidays: New Year’s Day (January 1), International Women’s Day (March 8), Navruz (Persian New Year, March 20, 21, or 22), International Labor Day (May 1), Victory Day (May 9), Independence Day (September 9), Constitution Day (November 6), and National Reconciliation Day (November 9). Flag: The flag features three horizontal stripes: a wide middle white stripe with narrower red (top) and green stripes. Centered in the white stripe is a golden crown topped by seven gold, five-pointed stars. The red is taken from the flag of the Soviet Union; the green represents agriculture and the white, cotton. The crown and stars represent the Click to Enlarge Image country’s sovereignty and the friendship of nationalities. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Early History: Iranian peoples such as the Soghdians and the Bactrians are the ethnic forbears of the modern Tajiks. They have inhabited parts of Central Asia for at least 2,500 years, assimilating with Turkic and Mongol groups. Between the sixth and fourth centuries B.C., present-day Tajikistan was part of the Persian Achaemenian Empire, which was conquered by Alexander the Great in the fourth century B.C. After that conquest, Tajikistan was part of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, a successor state to Alexander’s empire. -

Saint-Petersburg, Russia

Saint-Petersburg, Russia INGKA Centres Reaching out 13 MLN to millions VISITORS ANNUALLY Perfectly located to serve the rapidly developing districts direction. Moreover, next three years primary catchment area will of the Leningradsky region and Saint-Petersburg. Thanks significantly increase because of massive residential construction to the easy transport links and 98% brand awareness, MEGA in Murino, Parnas and Sertolovo. Already the go to destination Vyborg Parnas reaches out far beyond its immediate catchment area. in Saint-Petersburg and beyond, MEGA Parnas is currently It benefits from the new Western High-Speed Diameter enjoying a major redevelopment. And with an exciting new (WHSD) a unique high-speed urban highway being created design, improved atmosphere, services and customer care, in St. Petersburg, becoming a major transportation hub. the future looks even better. MEGA Parnas meets lots of guests in spring and summer period due to its location on the popular touristic and county house Sertolovo Sestroretsk Kronshtadt Vsevolozhsk Western High-Speed Diameter Saint-Petersburg city centre Catchment Areas People Distance Peterhof ● Primary 976,652 16 km Kirovsk ● Secondary 656,242 16–40 km 56% 3 МЕТRО 29% ● Tertiary 1,701,153 > 40–140 km CUSTOMERS COME STATIONS NEAR BY YOUNG Otradnoe BY CAR FAMILIES Total area: 3,334,047 Kolpino Lomonosov Sosnovyy Bor Krasnoe Selo A region with Loyal customers MEGA Parnas is located in the very dynamic city of St. Petersburg and attracts shoppers from all over St. Petersburg and the strong potential Leningrad region. MEGA is loved by families, lifestyle and experienced guests alike. St. Petersburg and the Leningrad region MEGA Parnas is situated in the north-east of St. -

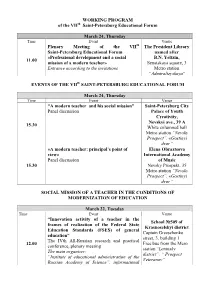

WORKING PROGRAM of the VII Saint-Petersburg Educational

WORKING PROGRAM of the VIIth Saint-Petersburg Educational Forum March 24, Thursday Time Event Venue Plenary Meeting of the VIIth The President Library Saint-Petersburg Educational Forum named after «Professional development and a social B.N. Yeltzin, 11.00 mission of a modern teacher» Senatskaya square, 3 Entrance according to the invitations Metro station “Admiralteyskaya” EVENTS OF THE VIIth SAINT-PETERSBURG EDUCATIONAL FORUM March 24, Thursday Time Event Venue “A modern teacher and his social mission” Saint-Petersburg City Panel discussion Palace of Youth Creativity, Nevskyi ave., 39 A 15.30 White columned hall Metro station “Nevsky Prospect”, «Gostinyi dvor” «A modern teacher: principal’s point of Elena Obraztsova view» International Academy Panel discussion of Music 15.30 Nevsky Prospekt, 35 Metro station “Nevsky Prospect”, «Gostinyi dvor” SOCIAL MISSION OF A TEACHER IN THE CONDITIONS OF MODERNIZATION OF EDUCATION March 22, Tuesday Time Event Venue “Innovation activity of a teacher in the School №509 of frames of realization of the Federal State Krasnoselskyi district Education Standards (FSES) of general Captain Greeschenko education” street, 3, building 1 The IVth All-Russian research and practical 12.00 Free bus from the Mero conference, plenary meeting station “Leninsky The main organizer: district”, “ Prospect “Institute of educational administration of the Veteranov” Russian Academy of Science”, informational and methodological center of Krasnoselskyi district of Saint-Petersburg, School №509 of Krasnoselskyi district March -

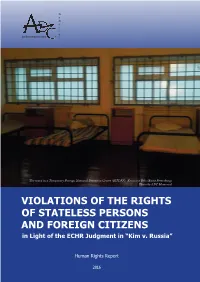

Violations of the Rights of Stateless Persons and Foreign Citizens in Light of the ECHR Judgment in “Kim V

m e m o r i a Anti-Discrimination Centre l The ward in a Temporary Foreign National Detention Center (SITDFN). Krasnoye Selo (Saint Petersburg) Photo by ADC Memorial VIOLATIONS OF THE RIGHTS OF STATELESS PERSONS AND FOREIGN CITIZENS in Light of the ECHR Judgment in “Kim v. Russia” Human Rights Report 2016 The Anti-discrimination Centre Memorial has spent many years defending the rights of people suffering form discrimination, and in particupar the rights of migrants and representatives of vulnerable minorities. This report describes negative impact of non-implementation of the ECHR judgement in “Kim v. Russia” (2014) on the situation of stateless persons and foreigners detained for months and years in “specialized institutions for the temporary detention” (SITDFN) in order «to guarantee the expultion». No access to legal aid, no judicial control of the term and soundness of deprivation of freedom, no legal opportunities of expulsion in case of stateless persons, inhuman conditions of detention in SITDFN – all this makes the life in “specialized institutions” a cruel punishment for people who did not commit any crimes. The problem of stateless persons and migrants in irregular situation is important not only for Russia and ex-Soviet countries, but for contemporary Europe as well; the ECHR judgement in “Kim v. Russia” should be taken into account by the countries who are members of the Council of Europe and the European Union. ADC Memorial is thankful to Viktor Nigmatulin, a detainee of SITDFN in Kemerovo (Siberis), for the materials provided for the report. TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary . 3 Preface STATELESSNESS AS A RESULT OF THE COLLAPSE OF THE SOVIET UNION . -

Apm 2006 Book of Abstracts

XXXIV Summer School – Conference “Advanced Problems in Mechanics” June 25 – July 1, 2006, St. Petersburg (Repino), Russia APM 2006 BOOK OF ABSTRACTS http://www.apm.ruweb.net GENERAL INFORMATION APM 2006 is the thirty four in a series of annual summer schools held by Russian Academy of Sciences. The Summer school “Advanced Problems in Mechanics 2006” is organized by the Institute for Problems in Mechanical Engineering of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IPME RAS) under the patronage of the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS).The main purpose of the meeting is to gather specialists from different branches of mechanics to provide a platform for cross-fertilisation of ideas. HISTORY OF THE SCHOOL The first Summer School was organized by Ya.G. Panovko and his colleagues in 1971. In the early years the main focus of the School was on nonlinear oscillations of mechanical systems with a finite number of degrees of freedom. The School specialized in this way because at that time in Russia (USSR) there were held regular National Meetings on Theoretical and Applied Mechanics, and also there were many conferences on mechanics with a more particular specialization. After 1985 many conferences and schools on mechanics in Russia were terminated due to financial problems. In 1994 the Institute for Problems in Mechanical Engineering of the Russian Academy of Sciences restarted the Summer School. The traditional name of “Summer School” has been kept, but the topics covered by the School have been much widened, and the School has been transformed into an international conference. The topics of the conference cover now all fields of mechanics and associated into interdisciplinary problems. -

First Russian Schools for Muslims in Tbilisi (Georgia)

First Russian Schools for Muslims in Tbilisi (Georgia) Nani Gelovani Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Faculty of Humanities, Institute of Oriental Studies, Associated professor; Georgia ABSTRACT The city of Tbilisi (its pre-1936 international designation – Tiflis), which became a center of Russian Administration in the Caucasus region since 1801, a residence of the Caucasus Viceroy (Namestnik) since 1845 and an administrative center of Tbilisi Governorate since 1846, was gradually established as an administrative, trade and industrial center of the South Caucasus (Transcaucasia). Through Tbilisi, Russia established diplomatic and trade relations with Eastern countries. In 1847-1849, the first Russian schools for Muslims in the South Caucasus, separately for Shiites and Sunnis, were opened in Tbilisi specifically, where the Caucasus Viceroy could closely supervise “the progress and success of this establishment”. This first experience of Muslim schools was a success: the population, who refrained from sending their children to parochial schools for religious reasons, showed sympathy to them. Opening educational establishments for Muslims controlled by the Tsarist Administration in the South Caucasus can be explained by Russia’s interest to promote the swift adaptation of the Muslims of the South Caucasus to Russian legal and cultural environment and by the need for training clerks among local residents to work at the Administration. The present report will consider the history of the first Russian Muslim schools in the South Caucasus, in Tbilisi in particular (charter, educational program, teaching aids, pedagogical staff, privileges for the graduates, estimate, etc.) based on the materials found in the archival documents and periodicals. Key words: Archival documents; Education; Russian Empire; South Caucasus; Tbilisi. -

Print This Article

Architecture and Engineering Volume 3 Issue 3 DISAPPEARED HISTORIC OPEN SPACES IN THE CENTER OF SAINT PETERSBURG Leonid Lavrov1, Fedor Perov2 1,2 Saint Petersburg State University of Architecture and Civil Engineering 2-ya Krasnoarmeiskaya st., 4, St. Petersburg, Russia 1 [email protected] Abstract The paper questions the official statement that the system of open spaces in the historic center of Saint Petersburg has preserved the "authenticity of its chief components". Conditions for the formation and subsequent reconstructions of Theater Square and areas adjacent to the Neva river are analyzed. The nature and scope of changes those areas undergone in the latter half of the 19th and early 20th centuries are identified. It is shown that Senate, Admiralty, Rumyantsev, Collegiate squares and Razvodnaya ground (used for the changing of the guard) lost their transparency which disturbed the relationship between the Neva water area and city open spaces, and that significant damage was caused to the city center panorama. It is noted that the center landscape potential was neglected due to that reason. Proposals are made to recreate the lost transparency of the city center public spaces. Keywords Landscapes of the historic center of Saint Petersburg, open spaces, reconstruction. Introduction of Monuments"). It was further emphasized that "the initial It is generally acknowledged that one of the city layout and a large portion of the original structures architectural features of the Saint Petersburg historic in Saint Petersburg's historic centre are testament to its center is its "single continuous open space formed Outstanding Universal Value... integrated value as the by rivers and canals, squares, avenues, streets and Historic Urban Landscape." However, the suggested gardens" (Shvidkovsky, 2007). -

PDF Download

INDOOR AIR Q~ALITY IN MUSEUMS AND HISTORICAL BUILDINGS IN ST. PETERSBURG AND IN NORTH-WEST REGION OF RUSSIA V.D.Korkin Institute of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture by name I.Repi& Russia ABSTRACT This presentation deals with the problem of achieving stable microclimate in old buddmgs of St Petersburg - such as churches, museums and palaces. Characteristic traits of such buildings are rather thick envelops which as a rule accumulate large quantities of heat or cold. The majority of these buildings are equipped only with central water heating and are naturally ventilated. Experimental study of microclimate in buildings of this kind proves that during cold season (with average temperature -10”C)the relative humidity there will be about 30-35% and less. In summer time temperature background does not rise above 22-24°C whereas the relative humidity sometimes can rise up to 75-80Y0. Eventually we should like to note that climate parameters of St Petersburg can be taken as a characteristic for entire Norten-West of Russia. Inserting into such buildings air conditioning systems (provided with cooling plants and devices for automatic control) does not aways give positive results. With consideration of climate features of the region and peculiarities of the buildings we worked out system which helps to maintain stable microclimate, special attention to thermrd inertia of walls included. This decision will give an oppotiunity to reduce a load on heating system at any rate to 15-20%. It will also give the chance for adiabatic humidity control in winter which is nessessary for the humidity control.