Parental Alienation, DSM-V, and ICD-11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ta and Milton Erickson. by Marnie Mcgann

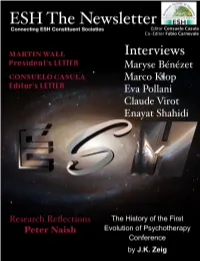

Table of Contents President’s Letter Martin Wall I start this letter with a meditation on per- ethical use of hypnosis to those ends. I spective, an image of earth taken from am always encouraged by the contacts I the outer edges of our solar system and have with our constituent societies, be- a quote from Carl Sagan – “…. a mote cause it reminds me every time that the- of dust, suspended in a sunbeam." re is a consistent wish to be part of so- We live in interesting times and as Euro- mething more than is encompassed in peans we watch as our cooperative their national boundaries. I am in full unity is threatened by fear, anxiety and agreement with Professor Loriedo’s political agenda. We are a European So- views, expressed in the last NL, with re- ciety of health care professionals who gard to enabling international joint re- are ethically and professionally commit- search projects, and to the setting of in- ted to caring for all who need our skills ternational standards in training and with kindness and compassion. I believe competency. These are ambitious and that a primary role of ESH is to support complex ambitions of course, but every all of our members in the effective and journey starts with the first step, and I 2 want to share with you some of the our members, and also with an ambition steps ESH is taking. to form a ‘research hub’, with facilities for collecting and exchanging data and • Research ideas between our international consti- We are proposing to engage ECH hol- tuencies. -

English Curriculum

Studio dell’ Avv. Pier Giacinto Di Fiore Napoli, 80143, Via Giovanni Porzio, Centro Direzionale, Isola F4, 18^ piano, int.100. Tel. 081 7347319; 333 4836287; fax: 081 19668236. Acerra (Na), 80011, Via Roma nr.6 – angolo via Duomo. Tel.: 081 5200415 - 338 4202185; fax: 081 19668236. P.E.C.: [email protected] ------- Official Web Site: www.difiorelex.it Patrocinante in Cassazione ed innanzi alle Giurisdizioni Superiori. Avv. Pier Giacinto Di Fiore. Specializzato in Diritto e Procedura Penale nell’ Unione Camere Penali Italiane Scuola Superiore dell’Avvocatura Fondazione del Consiglio Nazionale Forense. Avv. Eduardo Perri. del Foro di Napoli. Avv. Valerio Di Mauro del Foro di Nola. English curriculum. The lawyer Pier Giacinto Di Fiore, was born in Acerra the 08/10/1970, a high school diploma at Liceo Statale classical Vittorio Imbriani to Pomigliano d'Arco, graduating in Law in the University of Naples Federico II, with a thesis between parliamentary law and criminal procedure, on the powers of parliamentary committees of inquiry for investigation into relationship with the judicial investigator. Occupy jobs in the forensic study of Professor Vincenzo Spiezia, formerly professor of Criminal Procedure at the University of Naples Federico II, under the guidance’s lawyer Bruno Henry Spiezia, Supreme Court of the Forum of Nola. During his active practicing lawyer followed the important processes of the Court, Court of Assizes, Court of Appeals, the Supreme Court for crimes in the area of organized crime against public order, against the government, against the person, against the economy, against the property. Simultaneously with the criminal process and with equal commitment and authority, perform studies on the Criminal Law of Labor. -

Juridical Psychology - Guglielmo Gulotta, Antonietta Curci

PSYCHOLOGY – Vol .III - Juridical Psychology - Guglielmo Gulotta, Antonietta Curci JURIDICAL PSYCHOLOGY Guglielmo Gulotta Criminal lawyer, Full Professor of Forensic Psychology, University of Turin, Italy With the collaboration of Antonietta Curci Researcher in General Psychology, University of Bari, Italy Keywords: Juridical psychology, criminal psychology, legal psychology, forensic psychology, re-educative psychology, legislative psychology, psychological law, history of juridical psychology, psychotherapeutic law Contents 1. Introduction 2. The History of Juridical Psychology (with the collaboration of Antonietta Curci) 3. Psychological Law 4. Psychotherapeutic Law Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary Juridical psychology constitutes an interface between psychology and law. Its origins can be traced to the beginning of the twentieth century and it has now attained scientific autonomy. It is possible to distinguish juridical psychology in many fields of application: judicial psychology, criminal psychology, legal psychology, forensic psychology, re-educative psychology, and legislative psychology. The use of psychology can be both direct and indirect. It is direct if scientific content is strictly considered, as, for instance, in the evaluation of defendants’ personalities or the memory of eyewitnesses. It is indirect if psychological methods are used, as, for instance, to establish and improve diagnostic techniques in expertise or cross- examination. Moreover,UNESCO psychology can aid the law – to striEOLSSve toward a truthful reconstruction of reality. Indeed, the focus of trials is not historical reality, but the construction of a new reality that tendsSAMPLE towards historical reality through CHAPTERS all available procedural means. During World War I, psychologists worked especially as psychometricians, supervised by psychiatrists, interested in the use of the lie detector. They were also dealing with victims of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). -

41° Aggiornamento Sommari Riviste Scientifiche E Libri OSC Settembre

INTRODUZIONE p. 2 RECENSIONE p. 3 INTERNET p. 4 LIBRI :nuove acquisizioni p. 9 INDICI RIVISTE p. 58 1 INTRODUZIONE Gli aggiornamenti della biblioteca del Centro documentazione e ricerca OSC si rivolgono agli operatori dell'OSC e alle persone ed enti esterni interessati. Lo scopo è di fornire un'utile strumento di consultazione concernente la documentazione immediatamente disponibile ed aggiornata (libri, riviste, articoli di riviste), e in particolare gli articoli scientifici di cui si possono ottenere le fotocopie. L'aggiornamento che vi proponiamo, è il 41° da quando, nel 1987, abbiamo dato avvio a questa iniziativa. Questo fascicolo contiene: • i sommari dei nuovi numeri apparsi tra settembre 2004 e agosto 2005 di 46 titoli di riviste scelte fra tutte quelle ricevute regolarmente. • l’elenco dei libri acquisiti, lavori di diploma compresi (315 titoli ordinati al primo autore, solo quelli pubblicati nell’anno 2000 e seguenti); • la segnalazione di alcune banche dati consultabili gratuitamente in internet e l’elenco delle nostre riviste che hanno un sito web con i sommari dei numeri apparsi ed in alcuni casi anche il testo integrale. Nella sezione recensioni proponiamo in questo numero il riassunto della relazione del 15 nov. 2005 di Giuseppe Guaiana e Giuseppe Mariconda sull’équipe curante ed emotività espressa. La banca dati della biblioteca del Centro comprende ora globalmente circa 11'457 referenze bibliografiche tra cui 5'643 titoli di libri, 84 di riviste ricevute regolarmente e 157 di periodici non rinnovati o che hanno cessato la pubblicazione, 753 titoli di lavori di diploma, 4'543 di articoli specialistici e 234 di videocassette. -

Ejtn Catalogue Plus Seminar

11 - 13 FEBRUARY 2019 SCANDICCI, ITALY Villa Castelpulci, Via di Castelpulci, 43 EJTN CATALOGUE PLUS SEMINAR PSYCHOLOGY AND THE COURT – CP/2019/36 With financial support from the Justice Programme of the European Union The course will focus on a deeper understanding of the neuroscience, of whether and how emotions, mental psychological aspects of court work. The judge arrives at a processes of an intuitive nature or prejudices can influence formulation of the judgement through a process of complex the very perception of the reality of the trial, the reasoning, characterised by a perception of the facts, the appreciation of evidence and the psychology of judgment. right sequencing of the events, their coordinated analysis, In short, it is a question of verifying how psychology can up to their final synthesis. To do this, the judge must be help the judge to avoid errors in his own reasoning. "third" party and therefore clearly neutral, but at the same It is therefore necessary to reflect in depth on the mental time live and "feel" in a social dimension, so to distance path underlying the decision, and on the judgment, which himself from reality, though at the same time not to often also involves the relationship with public opinion. separate from it. And reality is never objectively With the support of experts in psychology and cognitive defined: its knowledge is the result of a complex sciences, we will reflect on the best possible way to manage relationship, in which many factors, mainly subjective, the energies correlated with judgment, we will see how come into play: in short, the subjectivity of the judge, his motivations, intuitive and controlled cognitive processes, personality, his emotions, his psyche. -

Comune Di Mantova Biblioteca Gino Baratta Fondo Ulisse Bresciani

Comune di Mantova Biblioteca Gino Baratta Fondo Ulisse Bresciani Fondo Ulisse Bresciani 1 *101 storie zen / a cura di Nyogen Senzaki / [a cura del Museo della storia cinese di e Paul Reps. - Milano : Adelphi, 1973. - Pechino ; Seminario di lingua e letteratura 110 p. ; 18 cm. ((Trad. di Adriana Motti. cinese dell'Universita degli studi di Venezia inv. 136962 ; Istituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente]. - Milano : Silvana, 1983. - 211 p. : UB.a.1289 ill. ; 25 cm. ((Catalogo della Mostra "7000 1 v anni di Cina a Venezia" tenuta a Venezia nel 1983. 2 *32 poesie / William Blake ; traduzione di inv. 138105 Giuseppe Ungaretti. - Milano : A. UB.a.1776 Mondadori, 1997. - 62 p. ; 16 cm. 1 v inv. 133462 FUB.40 8 *Abc per capire l'omosessualità / Obiettivo 1 V Chaire. - Cinisello Balsamo :San Paolo, c2005. - 62 p. : ill. ; 21 cm. 3 *387 d.C. : Ambrogio e Agostino : le inv. 133946 sorgenti dell'Europa : Milano, Museo FUB.101 Diocesano, Chiostri di Sant'Eustorgio, 8 dicembre 2003 - 2 maggio 2004. - [S.l. : 1 V s.n.], 200?. - 1 v. : ill. ; 24 cm. ((In testa al front.: Regione Lombardia; Fondazione 9 L'*aborto nella discussione teologica Sant'Ambrogio, Museo Diocesano, Chiostri cattolica / a cura di Gianangelo Palo ; di Sant'Eustorgio. Alfons Auer ... [et al.]. - Brescia : inv. 138164 Queriniana, 1977. - 255 p. ; 20 cm. UB.b.114 inv. 133223 1 v UB.a.372 1 V 4 Il *4. centenario della morte di San Luigi Gonzaga (1591-1991). - Guidizzolo 10 *A cavallo del tempo : sette racconti : (Mantova) : [s.n.], 1992. - 95 p. : ill. -

PASG Members Are Also Interested in Developing and Promoting Research on the Causes, Evaluation, Prevention, and Treatment of Parental Alienation

MEMBERS OF PARENTAL ALIENATION STUDY GROUP March 8, 2021 The Parental Alienation Study Group (PASG) consists of about 770 individuals, mostly mental health professionals, from 62 countries, including: Afghanistan, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Bangla- desh, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, Columbia, Costa Rica, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Egypt, Fiji, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hong Kong, Hungary, Iceland, India, Indonesia, Iran, the Republic of Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Kenya, Lithuania, Macedonia, Malaysia, Malta, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Nigeria, Norway, Paraguay, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Saudi Ara- bia, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, Trini- dad and Tobago, Turkey, Ukraine, United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom (including England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland), and the United States (including Puerto Rico). The members of PASG agree that parental alienation should be included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fifth Edition (DSM-5) and the International Classification of Dis- eases – Eleventh Edition (ICD-11). PASG is an international, not-for-profit corporation. The members of PASG are interested in educating the general public, mental health clinicians, forensic practitioners, at- torneys, and judges regarding parental alienation. PASG members are also interested in developing and promoting research on the causes, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of parental alienation. PASG is an open membership organization. We welcome professionals (such as psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers, attorneys, and judges) and nonprofessionals (such as alienated parents and grandparents and adult children of parental alienation). PASG does not certify that its members have any particular expertise. Inclusion in this list of members does not represent an endorsement from PASG. -

Download Download

UNVEILING WRONGFUL CONVICTIONS BETWEEN THE U.S. AND ITALY 101 Unveiling Wrongful Convictions Between the U.S. and Italy: Cross-Learning From Each Other’s Mistakes Luca Lupária Full Professor of Criminal Procedure at the University of Rome III. Director of the Italy Innocence Project. President of the European Innocence Network. Chiara Greco Ph.D. Candidate in “Law and Social Change” at the University of Rome III.1 This paper focuses on the issue of wrongful convictions as it emerged in the U.S.A. during the nineties and subsequently gained attention throughout Europe. The first part focuses on the factors that have brought the issue of wrongful convictions to light and on the impact that the American experience has had on the European Criminal Systems’ acknowledgment of the problem. The second part suggests that the perspective of the Italian jurist might be privileged when confronted with the topic of wrongful convictions, as the Italian criminal justice system was designed to combine the best aspects of both inquisitorial and adversarial systems. For this reason, one would expect the Italian system as generating few wrongful convictions. Facts and figures, however, do not support this expectation. The third part therefore focuses on those that might be the main causes for wrongful convictions within the Italian system, and it subsequently points out one major flaw of the Italian approach to the issue of wrongful convictions: the absence of a national database providing detailed information on previous cases of wrongful convictions. The paper then takes the U.S. National Registry of Exonerations and the establishment of conviction integrity units as positive examples from which Italy should learn. -

Europass Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Personal information First name(s) / Surname(s) Georgia Zara, Ph.D, BPS Charterd Psychol. E-mail [email protected] Pec [email protected] Nazionalità Italiana Indirizzo univesitario Università degli Studi di Torino Palazzo Badini Dipartimento di Psicologia Via Verdi, 10 10124 Torino Residenza Torino Contatto telefonico +39 011. 670 3069 universitario Ambito professionale Accademia: Dipartimento di Psicologia – Università degli Studi di Torino. Professore Associato confermato - SSD: M-PSI/05 presso il Dipartimento di Psicologia, Università degli Studi di Torino. Posizione accademica italiana attuale Presidente del Corso di Laurea magistrale interdipartimentale in Psicologia criminologica e forense, dell’Università degli Studi di Torino Membro del Collegio di Disciplina d’Ateneo, Università degli Studi di Torino. Membro della Commissione Didattica del Dipartimento di Psicologia, Università degli Studi di Torino (2019–). Posizione accademica Vice-Presidente del Corso di Laurea magistrale interdipartimentale in Psicologia italiana recente criminologica e forense (2016 – Novembre 2019), Università degli Studi di Torino. Presidente del Corso di Laurea magistrale interdipartimentale in Psicologia criminologica e forense, Università degli Studi di Torino (2013–2016). Membro della Giunta del Dipartimento di Psicologia, Università degli Studi di Torino (2012 – 2014). Membro della Commissione Didattica del Dipartimento di Psicologia, Università degli Studi di Torino (2012 – 2016). Membro del Comitato Bioetico di Ateneo (CBA), Università degli Studi di Torino (2009–2018). Docenza universitaria Docente di Psicologia criminologica e Risk assessment (area disciplinare: M PSI/05) e di Psicologia clinica forense e Criminologia clinica (M-PSI/05 e MPSI/08) nel Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Psicologia criminologica e forense, Università degli Studi di Torino. -

Scarica in Formato

Curriculum Vitae Personal information First name(s) / Surname(s) Georgia Zara, Ph.D, BPS Charterd Psychol. E-mail . Pec . Nazionalità . Indirizzo univesitario . Contatto telefonico . universitario Ambito professionale Accademia: Dipartimento di Psicologia – Università degli Studi di Torino. Professore Associato confermato - SSD: M-PSI/05 presso il Dipartimento di Psicologia, Università degli Studi di Torino. Posizione accademica Presidente del Corso di Laurea magistrale interdipartimentale in Psicologia criminologica e forense, dell’Università degli Studi di Torino italiana attuale Membro del Collegio di Disciplina d’Ateneo, Università degli Studi di Torino. Membro della Commissione Didattica del Dipartimento di Psicologia, Università degli Studi di Torino (2019–). Posizione accademica Vice-Presidente del Corso di Laurea magistrale interdipartimentale in Psicologia italiana recente criminologica e forense (2016 – Novembre 2019), Università degli Studi di Torino. Presidente del Corso di Laurea magistrale interdipartimentale in Psicologia criminologica e forense, Università degli Studi di Torino (2013–2016). Membro della Giunta del Dipartimento di Psicologia, Università degli Studi di Torino (2012 – 2014). Membro della Commissione Didattica del Dipartimento di Psicologia, Università degli Studi di Torino (2012 – 2016). Membro del Comitato Bioetico di Ateneo (CBA), Università degli Studi di Torino (2009–2018). Docenza universitaria Docente di Psicologia criminologica e Risk assessment (area disciplinare: M PSI/05) e di Psicologia clinica forense e Criminologia clinica (M-PSI/05 e MPSI/08) nel Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Psicologia criminologica e forense, Università degli Studi di Torino. Docente di Elementi di Psicologia giuridica e deontologia (M-PSI/05), nel Corso di Laurea Triennale in Scienze e tecniche psicologiche, Dipartimento di 1 Psicologia, Università degli Studi di Torino. -

PARENTAL ALIENATION, DSM-5, and ICD-11 Publication Number 1113

PARENTAL ALIENATION, DSM-5, AND ICD-11 Publication Number 1113 AMERICAN SERIES IN BEHAVIORAL SCIENCE AND LAW Edited by RALPH SLOVENKO, B.E., LL.B., M.A., Ph.D. Professor of Law and Psychiatry Wayne State University Law School Detroit, Michigan PARENTAL ALIENATION, DSM-5, AND ICD-11 Edited by WILLIAM BERNET, M.D. Professor, Department of Psychiatry Vanderbilt University School of Medicine Nashville, Tennessee Published and Distributed Throughout the World by CHARLES C THOMAS • PUBLISHER, LTD. 2600 South First Street Springfield, Illinois 62794-9265 This book is protected by copyright. No part of it may be reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher. All rights reserved. © 2010 by CHARLES C THOMAS • PUBLISHER, LTD. ISBN 978-0-398-07944-4 (hard) ISBN 978-0-398-07945-1 (paper) Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2010012349 With THOMAS BOOKS careful attention is given to all details of manufacturing and design. It is the Publisher’s desire to present books that are satisfactory as to their physical qualities and artistic possibilities and appropriate for their particular use. THOMAS BOOKS will be true to those laws of quality that assure a good name and good will. Printed in the United States of America MM-R-3 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Parental alienation, DSM-5, and ICD-11 / edited by William Bernet. p. cm. “Publication Number 1113”—Ser. t.p. Includes biographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-398-07944-4 (hard)—ISBN 978-0-398-07945-1 (pbk.) 1. Parental alienation syndrome—Diagnosis. 2. Parental alienation syn- drome—Classification.