1 the Fifth Century Crisis1 This Essay Seeks to Establish the Parameters Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BILLING and CODING: NERVE BLOCKADE for TREATMENT of CHRONIC PAIN and NEUROPATHY (A56034) Links in PDF Documents Are Not Guaranteed to Work

Local Coverage Article: BILLING AND CODING: NERVE BLOCKADE FOR TREATMENT OF CHRONIC PAIN AND NEUROPATHY (A56034) Links in PDF documents are not guaranteed to work. To follow a web link, please use the MCD Website. Contractor Information Table 1: Contractor Information CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT CONTRACT JURISDICTION STATE(S) TYPE NUMBER Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01111 - MAC A J - E California - Entire State LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01112 - MAC B J - E California - Northern LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01182 - MAC B J - E California - Southern LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01211 - MAC A J - E American Samoa LLC Guam Hawaii Northern Mariana Islands Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01212 - MAC B J - E American Samoa LLC Guam Hawaii Northern Mariana Islands Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01311 - MAC A J - E Nevada LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01312 - MAC B J - E Nevada LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01911 - MAC A J - E American Samoa LLC California - Entire State Guam Hawaii Nevada Northern Mariana Islands Article Information General Information Created on 05/11/2021. Page 1 of 23 Article ID A56034 Article Title Billing and Coding: Nerve Blockade for Treatment of Chronic Pain and Neuropathy Article Type Billing and Coding AMA CPT / ADA CDT / AHA NUBC Copyright Statement CPT codes, descriptions and other data only are copyright 2020 American Medical Association. All Rights Reserved. Applicable FARS/HHSARS apply. Fee schedules, relative value units, conversion factors and/or related components are not assigned by the AMA, are not part of CPT, and the AMA is not recommending their use. -

Journeys to Byzantium? Roman Senators Between Rome and Constantinople

Journeys to Byzantium? Roman Senators Between Rome and Constantinople Master’s Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Michael Anthony Carrozzo, B.A Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2010 Thesis Committee: Kristina Sessa, Advisor Timothy Gregory Anthony Kaldellis Copyright by Michael Anthony Carrozzo 2010 Abstract For over a thousand years, the members of the Roman senatorial aristocracy played a pivotal role in the political and social life of the Roman state. Despite being eclipsed by the power of the emperors in the first century BC, the men who made up this order continued to act as the keepers of Roman civilization for the next four hundred years, maintaining their traditions even beyond the disappearance of an emperor in the West. Despite their longevity, the members of the senatorial aristocracy faced an existential crisis following the Ostrogothic conquest of the Italian peninsula, when the forces of the Byzantine emperor Justinian I invaded their homeland to contest its ownership. Considering the role they played in the later Roman Empire, the disappearance of the Roman senatorial aristocracy following this conflict is a seminal event in the history of Italy and Western Europe, as well as Late Antiquity. Two explanations have been offered to explain the subsequent disappearance of the Roman senatorial aristocracy. The first involves a series of migrations, beginning before the Gothic War, from Italy to Constantinople, in which members of this body abandoned their homes and settled in the eastern capital. -

The Evolution of the Roman Calendar Dwayne Meisner, University of Regina

The Evolution of the Roman Calendar Dwayne Meisner, University of Regina Abstract The Roman calendar was first developed as a lunar | 290 calendar, so it was difficult for the Romans to reconcile this with the natural solar year. In 45 BC, Julius Caesar reformed the calendar, creating a solar year of 365 days with leap years every four years. This article explains the process by which the Roman calendar evolved and argues that the reason February has 28 days is that Caesar did not want to interfere with religious festivals that occurred in February. Beginning as a lunar calendar, the Romans developed a lunisolar system that tried to reconcile lunar months with the solar year, with the unfortunate result that the calendar was often inaccurate by up to four months. Caesar fixed this by changing the lengths of most months, but made no change to February because of the tradition of intercalation, which the article explains, and because of festivals that were celebrated in February that were connected to the Roman New Year, which had originally been on March 1. Introduction The reason why February has 28 days in the modern calendar is that Caesar did not want to interfere with festivals that honored the dead, some of which were Past Imperfect 15 (2009) | © | ISSN 1711-053X | eISSN 1718-4487 connected to the position of the Roman New Year. In the earliest calendars of the Roman Republic, the year began on March 1, because the consuls, after whom the year was named, began their years in office on the Ides of March. -

Ritual Cleaning-Up of the City: from the Lupercalia to the Argei*

RITUAL CLEANING-UP OF THE CITY: FROM THE LUPERCALIA TO THE ARGEI* This paper is not an analysis of the fine aspects of ritual, myth and ety- mology. I do not intend to guess the exact meaning of Luperci and Argei, or why the former sacrificed a dog and the latter were bound hand and foot. What I want to examine is the role of the festivals of the Lupercalia and the Argei in the functioning of the Roman community. The best-informed among ancient writers were convinced that these were purification cere- monies. I assume that the ancients knew what they were talking about and propose, first, to establish the nature of the ritual cleanliness of the city, and second, see by what techniques the two festivals achieved that goal. What, in the perception of the Romans themselves, normally made their city unclean? What were the ordinary, repetitive sources of pollution in pre-Imperial Rome, before the concept of the cura Urbis was refined? The answer to this is provided by taboos and restrictions on certain sub- stances, and also certain activities, in the City. First, there is a rule from the Twelve Tables with Cicero’s curiously anachronistic comment: «hominem mortuum», inquit lex in duodecim, «in urbe ne sepelito neve urito», credo vel propter ignis periculum (De leg. II 58). Secondly, we have the edict of the praetor L. Sentius C.f., known from three inscrip- tions dating from the beginning of the first century BC1: L. Sentius C. f. pr(aetor) de sen(atus) sent(entia) loca terminanda coer(avit). -

Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Bernard, Seth G., "Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C." (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 492. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Abstract MEN AT WORK: PUBLIC CONSTRUCTION, LABOR, AND SOCIETY AT MID-REPUBLICAN ROME, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard C. Brian Rose, Supervisor of Dissertation This dissertation investigates how Rome organized and paid for the considerable amount of labor that went into the physical transformation of the Middle Republican city. In particular, it considers the role played by the cost of public construction in the socioeconomic history of the period, here defined as 390 to 168 B.C. During the Middle Republic period, Rome expanded its dominion first over Italy and then over the Mediterranean. As it developed into the political and economic capital of its world, the city itself went through transformative change, recognizable in a great deal of new public infrastructure. -

Campaign Back Cover

PAXLEXQUE CampaignSetting AnRPGGame WorldSetting C OMPATIBLEW ITH ByEd&XuânStanek Thisproductiscompatiblewiththe DungeonCrawlClassicsRolePlayingGame. RaorgenGames ATLAS Lands of the Great Sea Region Primary Primary Land Leader Language Patron(s) Aegypt Pharaoh Menkefe Aegyptian Reku Aquitania independent villages Elven Tanalis Arabia King Aiman Arabic Elkev, Eliha Belgica independent clans Celtic druidic Betica King Noteres III Costapanian Iber Britania independent clans Celtic druidic Cypria independent villages Gnomish none Dacia King Detelin Dacian Ramasar Druzix independent villages Lizardfolk Savra Felicia independent clans Felid Ubaste Germania independent clans Germanic Mothis Hellena independent villages Elven Ellelliara Hispania King Gabriel II Palacian Iber Macedonia King Philognes Balkan Fortruvius, Procella Mauretania King Jubair Mauretani Hasbia (Procella) Meria independent villages Merfolk none Nurdarim King Hemdurum IV Dwarven Doraga Pamfilia independent villages Gnomish none Rome Emperor Socindus II Latin Celata, Fortruvius, Procella Scythia independent clans Centaur Ramasar Semosiss Lord Essemelessi Serpentine Savra Stonarx independent clans Goblin Gulyabani Syria King Isidorus Arabic Elkev, Eliha Talin independent clans Celtic Helet Thracia independent cities Dacian Procella 10 Hellena The land kissed by Ellelliara, the Light of Dawn, the land of rolling hills and rocky shores where artistic beauty is ubiquitous - that is Hellena, home of the high elves. Hellena can be welcoming to strangers of goodwill, but those with treacherous intent would be well advised to not confuse the elves’ gentle friendship with weakness. Geography Hellena is a rocky, uneven land of many peninsulas and a thousand islands amid the Pisconian Sea. This terrain has contributed to the relative isolation of each village and city in Hellena. The majority of Hellena’s cities are along the coast. -

The Edictum Theoderici: a Study of a Roman Legal Document from Ostrogothic Italy

The Edictum Theoderici: A Study of a Roman Legal Document from Ostrogothic Italy By Sean D.W. Lafferty A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto © Copyright by Sean D.W. Lafferty 2010 The Edictum Theoderici: A Study of a Roman Legal Document from Ostrogothic Italy Sean D.W. Lafferty Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto 2010 Abstract This is a study of a Roman legal document of unknown date and debated origin conventionally known as the Edictum Theoderici (ET). Comprised of 154 edicta, or provisions, in addition to a prologue and epilogue, the ET is a significant but largely overlooked document for understanding the institutions of Roman law, legal administration and society in the West from the fourth to early sixth century. The purpose is to situate the text within its proper historical and legal context, to understand better the processes involved in the creation of new law in the post-Roman world, as well as to appreciate how the various social, political and cultural changes associated with the end of the classical world and the beginning of the Middle Ages manifested themselves in the domain of Roman law. It is argued here that the ET was produced by a group of unknown Roman jurisprudents working under the instructions of the Ostrogothic king Theoderic the Great (493-526), and was intended as a guide for settling disputes between the Roman and Ostrogothic inhabitants of Italy. A study of its contents in relation to earlier Roman law and legal custom preserved in imperial decrees and juristic commentaries offers a revealing glimpse into how, and to what extent, Roman law survived and evolved in Italy following the decline and eventual collapse of imperial authority in the region. -

Newsletter Nov 2011

imperi nuntivs The newsletter of Legion Ireland --- The Roman Military Society of Ireland In This Issue • New Group Logo • Festival of Saturnalia • Roman Festivals • The Emperors - AD69 - AD138 • Beautifying Your Hamata • Group Events and Projects • Roman Coins AD69 - AD81 • Roundup of 2011 Events November 2011 IMPERI NUNTIUS The newsletter of Legion Ireland - The Roman Military Society of Ireland November 2011 From the editor... Another month another newsletter! This month’s newsletter kind grew out of control so please bring a pillow as you’ll probably fall asleep while reading. Anyway I hope you enjoy this months eclectic mix of articles and info. Change Of Logo... We have changed our logo! Our previous logo was based on an eagle from the back of an Italian Mus- solini era coin. The new logo is based on the leaping boar image depicted on the antefix found at Chester. Two versions exist. The first is for a white back- ground and the second for black or a dark back- ground. For our logo we have framed the boar in a victory wreath with a purple ribbon. We tried various colour ribbons but purple worked out best - red made it look like a Christmas wreath! I have sent these logo’s to a garment manufacturer in the UK and should have prices back shortly for group jackets, sweat shirts and polo shirts. Roof antefix with leaping boar The newsletter of Legion Ireland - The Roman Military Society of Ireland. Page 2 Imperi Nuntius - Winter 2011 The newsletter of Legion Ireland - The Roman Military Society of Ireland. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

The Fifth Century, the Decemvirate, and the Quaestorship

THE FIFTH CENTURY, THE DECEMVIRATE, AND THE QUAESTORSHIP Ralph Covino (University of Tennessee at Chattanooga). There has always been some question as to the beginnings of the regularized quaestorship. As long ago as 1936, Latte pointed out that there seems to be no Roman tradition as to the quaestors’ origins.1 As officials, they barely appear at all in the early Livian narrative. The other accounts which we possess, such as those of Tacitus and Ioannes Lydus, are unhelpful at best. While scholars such as Lintott and others have sought to weave together the disparate fragments of information that exist so as to construct a plausible timeline of events surrounding the first appearance of regular, elected quaestors in the middle of the fifth-century, it becomes apparent that there is a dimension that has been omitted. Magisterial offices, even ones without the power to command and to compel, imperium, do not appear fully-formed overnight. This paper seeks to uncover more of the process by which the regular quaestors emerged so as to determine how they actually came to be instituted and regularized rather than purely rely on that which we are told happened from the sources.2 Tacitus records that quaestors were instituted under the monarchs in a notoriously problematic passage: The quaestorship itself was instituted while the kings still reigned, as shown by the renewal of the curiate law by L. Brutus; and the power of selection remained with the consuls, until this office, with the rest, passed into the bestowal of the people. The first election, sixty-three years after the expulsion of the Tarquins, was that of Valerius Potitus and Aemilius Mamercus, as finance officials attached to the army in the field. -

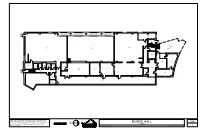

MORSE HALL CB N Floor # Fitness for a Particular Use

X170 150A 196 LOADING DN DOCK 180 170 150 UP DN X142 190F 190C 142 140 UP 190A 194 193 192 181 190B 170B 190E 170A 165 160 UP 190D 197 141 195 191 190 198 Building/Zone Western Washington University (WWU) makes these documents available on an "as is" basis. All warranties and representations of any kind with regard to said 0 8 16 documents are disclaimed, including the implied warranties of merchantability and TRUE MORSE HALL CB N Floor # fitness for a particular use. WWU does not warrant the documents against FT NORTH FLOOR 1 deficiencies of any kind. Date Revised: 12/13/2016 Last Sync With FAMIS: 09/22/2015 1 270B 270C 270A 275 270 270D 296 280 281 DN UP 290D 260 254 282 265 258 256 252 250 290N 245 283 284 290C 290W 244 290A 202 295 229 295A 230B 230A 201 210A 220A 290S 243 294 242 293 292 200 210 220 230 241 292A UP 291 200A 240 290E X290E Building/Zone Western Washington University (WWU) makes these documents available on an "as is" basis. All warranties and representations of any kind with regard to said 0 8 16 documents are disclaimed, including the implied warranties of merchantability and TRUE MORSE HALL CB N Floor # fitness for a particular use. WWU does not warrant the documents against FT NORTH FLOOR 2 deficiencies of any kind. Date Revised: 12/13/2016 Last Sync With FAMIS: 09/22/2015 2 386 385 387B 387A 383 390G 387 DN UP 396 382 380 370 360 350 388 390N 381 345 389 390C 390W 344 390S 395 310B 329 395A 310C 310A 330A 343 394 393 342 392 310 330 330B 341 392A UP 391 340 DN 390E ROOF BELOW BASE FLOOR PLAN Building Western Washington University (WWU) makes these documents available on an "as is" basis. -

3.2 Precipitation Or Dry-Wet Reconstructions

Climate change in China during the past 2000 years: An overview Ge Quansheng , Zheng Jingyun Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China Email: [email protected] Outline 1 Introduction 2 Historical Documents as Proxy 3 Reconstructions and Analyses 4 Summary and Prospects 1. Introduction: E Asia2K Climate System Socio-economic System •typical East Asian •dense population and rapid monsoon climate economic development • significant seasonal and • be susceptible to global inter-annual and inter- warming and extreme decadal variability climate events Climate change study in the past 2ka in East Asian is both beneficial and advantageous. • various types of natural proxy • Plenty of historical documents Fig. Active regional working groups under as proxy the past 2ka theme (PAGES 2009) 2. Historical Documents as Proxy Type Period Amount Chinese classical 1,531 kinds, 137 BC~1470 AD documents 32,251 volumes More than 8,000 1471~1911 (The Ming Local gazettes books (部), 110, and Qing Dynasty) 000 volumes Memos to the About 120,000 1736~1911 emperor pieces Archives of the 1912~1949 20,000 volumes Republic of China More than 200 Private diaries 1550~ books (部) Chinese classical documents AD 833, North China plain: Extreme drought event was occurred, crops were shriveling, no yields, people were in hungry…. Fig. Example for Ancient Chinese writings Local gazettes The 28th year of the Daoguang reign (1848 AD), the 6th (lunar) month, strong wind and heavy rain, the Yangtze River overflowed; the 7th month, strong wind Fig. Gazettes of Yangzhou Prefecture and thunder storm, field published in 1874 AD and houses submerged.