Hospitalitas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the D

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Marion Woodrow Kruse, III Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Anthony Kaldellis, Advisor; Benjamin Acosta-Hughes; Nathan Rosenstein Copyright by Marion Woodrow Kruse, III 2015 ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the use of Roman historical memory from the late fifth century through the middle of the sixth century AD. The collapse of Roman government in the western Roman empire in the late fifth century inspired a crisis of identity and political messaging in the eastern Roman empire of the same period. I argue that the Romans of the eastern empire, in particular those who lived in Constantinople and worked in or around the imperial administration, responded to the challenge posed by the loss of Rome by rewriting the history of the Roman empire. The new historical narratives that arose during this period were initially concerned with Roman identity and fixated on urban space (in particular the cities of Rome and Constantinople) and Roman mythistory. By the sixth century, however, the debate over Roman history had begun to infuse all levels of Roman political discourse and became a major component of the emperor Justinian’s imperial messaging and propaganda, especially in his Novels. The imperial history proposed by the Novels was aggressivley challenged by other writers of the period, creating a clear historical and political conflict over the role and import of Roman history as a model or justification for Roman politics in the sixth century. -

BILLING and CODING: NERVE BLOCKADE for TREATMENT of CHRONIC PAIN and NEUROPATHY (A56034) Links in PDF Documents Are Not Guaranteed to Work

Local Coverage Article: BILLING AND CODING: NERVE BLOCKADE FOR TREATMENT OF CHRONIC PAIN AND NEUROPATHY (A56034) Links in PDF documents are not guaranteed to work. To follow a web link, please use the MCD Website. Contractor Information Table 1: Contractor Information CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT CONTRACT JURISDICTION STATE(S) TYPE NUMBER Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01111 - MAC A J - E California - Entire State LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01112 - MAC B J - E California - Northern LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01182 - MAC B J - E California - Southern LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01211 - MAC A J - E American Samoa LLC Guam Hawaii Northern Mariana Islands Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01212 - MAC B J - E American Samoa LLC Guam Hawaii Northern Mariana Islands Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01311 - MAC A J - E Nevada LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01312 - MAC B J - E Nevada LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01911 - MAC A J - E American Samoa LLC California - Entire State Guam Hawaii Nevada Northern Mariana Islands Article Information General Information Created on 05/11/2021. Page 1 of 23 Article ID A56034 Article Title Billing and Coding: Nerve Blockade for Treatment of Chronic Pain and Neuropathy Article Type Billing and Coding AMA CPT / ADA CDT / AHA NUBC Copyright Statement CPT codes, descriptions and other data only are copyright 2020 American Medical Association. All Rights Reserved. Applicable FARS/HHSARS apply. Fee schedules, relative value units, conversion factors and/or related components are not assigned by the AMA, are not part of CPT, and the AMA is not recommending their use. -

Journeys to Byzantium? Roman Senators Between Rome and Constantinople

Journeys to Byzantium? Roman Senators Between Rome and Constantinople Master’s Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Michael Anthony Carrozzo, B.A Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2010 Thesis Committee: Kristina Sessa, Advisor Timothy Gregory Anthony Kaldellis Copyright by Michael Anthony Carrozzo 2010 Abstract For over a thousand years, the members of the Roman senatorial aristocracy played a pivotal role in the political and social life of the Roman state. Despite being eclipsed by the power of the emperors in the first century BC, the men who made up this order continued to act as the keepers of Roman civilization for the next four hundred years, maintaining their traditions even beyond the disappearance of an emperor in the West. Despite their longevity, the members of the senatorial aristocracy faced an existential crisis following the Ostrogothic conquest of the Italian peninsula, when the forces of the Byzantine emperor Justinian I invaded their homeland to contest its ownership. Considering the role they played in the later Roman Empire, the disappearance of the Roman senatorial aristocracy following this conflict is a seminal event in the history of Italy and Western Europe, as well as Late Antiquity. Two explanations have been offered to explain the subsequent disappearance of the Roman senatorial aristocracy. The first involves a series of migrations, beginning before the Gothic War, from Italy to Constantinople, in which members of this body abandoned their homes and settled in the eastern capital. -

037 690305 the Trans

Horld ElstorY >#9 h. Eoeb Hednesday P.t{. lEE TnAtrSIfIOnAt KII{GDUSs VAI{DI,LS' HEiltLI' OSIBT0ES lfter the Roam defeat bf tbe Vlaigoths at 441b,gs tn t8, rp bart the cqo- uautng eto:y of the collapse of tbe Rccdr &pfre ps fo:nd e pag€ 134 fn t+g"r. Stlllcho rt tll3 bottm of tb3 flrst col:uor rp dlscswr tbat tbe @ercr Bcrorlu a (9*t&3) rypolntect Ure VErSgl Stlllplro es Easter of tbe troops. Eere nas a sltaratlcn rbera a Uerlgqls EA ffid ofE-tbe nttltary forceel It rns not just tbat tbs C'€ina,s ;ffi-:y lrr charge of Ee rrall alorg tbe RhJ.ne, hrt,gon me of tbeo le tn obarge of tbe Rmm arry fneiae tbp r.ratl! Itrs ltke tbe cansLto nose under tbe tmt. far see litt&e ty ltttte rbat is bappentng I Golng to colu.m tvo: trr 406 Cauf. ras ,qP.rnm by Vmdals srd other trlltBs. dgpqf:re-of fn Lgt'51o tberc vas @ lccc'ed evaoratlor € Brltafg.-the..cglete t& troq>J- dates rnay:Er@g$E- sore sdrcAsErt f thl$k tbls is tbe elgplslg dg!g- for tho purposef\r1 evasusticn of the ls1ad. lnd then ln lueust of /+oB Sbilfpl*r l€g Elgl*g at Fcrelusr cdsrt ttt€ @ere did no[ tnrEt brs rnlrrtary c@EQs r.nre Just not golng rtght fcr tie fupire. Rm Sacked I relgn llotlce next that tbe @eror Theodoslus. erperor ll th9 9eg! $o b€99 -hie i" 4OS; ;i"*ua tbe earllest' colleffilf existLne lgggr tbe-lieodoela CodE.; l&eD yan_bave a good rJ"i6W bas to 16rltlply,-fi c1assl$r -md cod,l.$ none-art none latr, "tafc"trcn tbat socLety breatcnp'0gg, due to lncreased ccrlos srd Laltless:eegt lbea people ar€ Uun"":irg tb€r'selvee teet'e ls no need for a lot of lane. -

The Edictum Theoderici: a Study of a Roman Legal Document from Ostrogothic Italy

The Edictum Theoderici: A Study of a Roman Legal Document from Ostrogothic Italy By Sean D.W. Lafferty A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto © Copyright by Sean D.W. Lafferty 2010 The Edictum Theoderici: A Study of a Roman Legal Document from Ostrogothic Italy Sean D.W. Lafferty Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto 2010 Abstract This is a study of a Roman legal document of unknown date and debated origin conventionally known as the Edictum Theoderici (ET). Comprised of 154 edicta, or provisions, in addition to a prologue and epilogue, the ET is a significant but largely overlooked document for understanding the institutions of Roman law, legal administration and society in the West from the fourth to early sixth century. The purpose is to situate the text within its proper historical and legal context, to understand better the processes involved in the creation of new law in the post-Roman world, as well as to appreciate how the various social, political and cultural changes associated with the end of the classical world and the beginning of the Middle Ages manifested themselves in the domain of Roman law. It is argued here that the ET was produced by a group of unknown Roman jurisprudents working under the instructions of the Ostrogothic king Theoderic the Great (493-526), and was intended as a guide for settling disputes between the Roman and Ostrogothic inhabitants of Italy. A study of its contents in relation to earlier Roman law and legal custom preserved in imperial decrees and juristic commentaries offers a revealing glimpse into how, and to what extent, Roman law survived and evolved in Italy following the decline and eventual collapse of imperial authority in the region. -

Jordanes and the Invention of Roman-Gothic History Dissertation

Empire of Hope and Tragedy: Jordanes and the Invention of Roman-Gothic History Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Brian Swain Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Timothy Gregory, Co-advisor Anthony Kaldellis Kristina Sessa, Co-advisor Copyright by Brian Swain 2014 Abstract This dissertation explores the intersection of political and ethnic conflict during the emperor Justinian’s wars of reconquest through the figure and texts of Jordanes, the earliest barbarian voice to survive antiquity. Jordanes was ethnically Gothic - and yet he also claimed a Roman identity. Writing from Constantinople in 551, he penned two Latin histories on the Gothic and Roman pasts respectively. Crucially, Jordanes wrote while Goths and Romans clashed in the imperial war to reclaim the Italian homeland that had been under Gothic rule since 493. That a Roman Goth wrote about Goths while Rome was at war with Goths is significant and has no analogue in the ancient record. I argue that it was precisely this conflict which prompted Jordanes’ historical inquiry. Jordanes, though, has long been considered a mere copyist, and seldom treated as an historian with ideas of his own. And the few scholars who have treated Jordanes as an original author have dampened the significance of his Gothicness by arguing that barbarian ethnicities were evanescent and subsumed by the gravity of a Roman political identity. They hold that Jordanes was simply a Roman who can tell us only about Roman things, and supported the Roman emperor in his war against the Goths. -

The Fifth Century, the Decemvirate, and the Quaestorship

THE FIFTH CENTURY, THE DECEMVIRATE, AND THE QUAESTORSHIP Ralph Covino (University of Tennessee at Chattanooga). There has always been some question as to the beginnings of the regularized quaestorship. As long ago as 1936, Latte pointed out that there seems to be no Roman tradition as to the quaestors’ origins.1 As officials, they barely appear at all in the early Livian narrative. The other accounts which we possess, such as those of Tacitus and Ioannes Lydus, are unhelpful at best. While scholars such as Lintott and others have sought to weave together the disparate fragments of information that exist so as to construct a plausible timeline of events surrounding the first appearance of regular, elected quaestors in the middle of the fifth-century, it becomes apparent that there is a dimension that has been omitted. Magisterial offices, even ones without the power to command and to compel, imperium, do not appear fully-formed overnight. This paper seeks to uncover more of the process by which the regular quaestors emerged so as to determine how they actually came to be instituted and regularized rather than purely rely on that which we are told happened from the sources.2 Tacitus records that quaestors were instituted under the monarchs in a notoriously problematic passage: The quaestorship itself was instituted while the kings still reigned, as shown by the renewal of the curiate law by L. Brutus; and the power of selection remained with the consuls, until this office, with the rest, passed into the bestowal of the people. The first election, sixty-three years after the expulsion of the Tarquins, was that of Valerius Potitus and Aemilius Mamercus, as finance officials attached to the army in the field. -

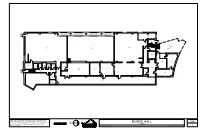

MORSE HALL CB N Floor # Fitness for a Particular Use

X170 150A 196 LOADING DN DOCK 180 170 150 UP DN X142 190F 190C 142 140 UP 190A 194 193 192 181 190B 170B 190E 170A 165 160 UP 190D 197 141 195 191 190 198 Building/Zone Western Washington University (WWU) makes these documents available on an "as is" basis. All warranties and representations of any kind with regard to said 0 8 16 documents are disclaimed, including the implied warranties of merchantability and TRUE MORSE HALL CB N Floor # fitness for a particular use. WWU does not warrant the documents against FT NORTH FLOOR 1 deficiencies of any kind. Date Revised: 12/13/2016 Last Sync With FAMIS: 09/22/2015 1 270B 270C 270A 275 270 270D 296 280 281 DN UP 290D 260 254 282 265 258 256 252 250 290N 245 283 284 290C 290W 244 290A 202 295 229 295A 230B 230A 201 210A 220A 290S 243 294 242 293 292 200 210 220 230 241 292A UP 291 200A 240 290E X290E Building/Zone Western Washington University (WWU) makes these documents available on an "as is" basis. All warranties and representations of any kind with regard to said 0 8 16 documents are disclaimed, including the implied warranties of merchantability and TRUE MORSE HALL CB N Floor # fitness for a particular use. WWU does not warrant the documents against FT NORTH FLOOR 2 deficiencies of any kind. Date Revised: 12/13/2016 Last Sync With FAMIS: 09/22/2015 2 386 385 387B 387A 383 390G 387 DN UP 396 382 380 370 360 350 388 390N 381 345 389 390C 390W 344 390S 395 310B 329 395A 310C 310A 330A 343 394 393 342 392 310 330 330B 341 392A UP 391 340 DN 390E ROOF BELOW BASE FLOOR PLAN Building Western Washington University (WWU) makes these documents available on an "as is" basis. -

3.2 Precipitation Or Dry-Wet Reconstructions

Climate change in China during the past 2000 years: An overview Ge Quansheng , Zheng Jingyun Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China Email: [email protected] Outline 1 Introduction 2 Historical Documents as Proxy 3 Reconstructions and Analyses 4 Summary and Prospects 1. Introduction: E Asia2K Climate System Socio-economic System •typical East Asian •dense population and rapid monsoon climate economic development • significant seasonal and • be susceptible to global inter-annual and inter- warming and extreme decadal variability climate events Climate change study in the past 2ka in East Asian is both beneficial and advantageous. • various types of natural proxy • Plenty of historical documents Fig. Active regional working groups under as proxy the past 2ka theme (PAGES 2009) 2. Historical Documents as Proxy Type Period Amount Chinese classical 1,531 kinds, 137 BC~1470 AD documents 32,251 volumes More than 8,000 1471~1911 (The Ming Local gazettes books (部), 110, and Qing Dynasty) 000 volumes Memos to the About 120,000 1736~1911 emperor pieces Archives of the 1912~1949 20,000 volumes Republic of China More than 200 Private diaries 1550~ books (部) Chinese classical documents AD 833, North China plain: Extreme drought event was occurred, crops were shriveling, no yields, people were in hungry…. Fig. Example for Ancient Chinese writings Local gazettes The 28th year of the Daoguang reign (1848 AD), the 6th (lunar) month, strong wind and heavy rain, the Yangtze River overflowed; the 7th month, strong wind Fig. Gazettes of Yangzhou Prefecture and thunder storm, field published in 1874 AD and houses submerged. -

Fall of the Western Empire "Migration" Or "Invasion"? the Beginning

1 Fall of the Western Empire "Migration" or "Invasion"? The Beginning of the "Dark Ages" Replacement of a "Worn Out Society" with New Vigorous Peoples Elements of Truth in Both Positions Rural Romans not Very Different From Germanic Peoples Germanic Tribes Move Southward Against the Roman Borders Possible Factors Deteriorating Weather / Climate Crop Failures in North Increased Population The Huns Map Cavalry Force Tribes First Enter Europe ca. 370 The Hunnic Empire (370-469) Rome's Answer: Foederati Battle of Hadrianople (378) Visigoths 2 Established in Roman Empire as Foederati Alaric Invades Italy (409) Sacks Rome (Aug. 24, 410) Impact Jerome, Commentary on Ezekiel Aftermath Latifundia vs. Political Engagement Western Roman Empire Gradually Given Over to Germanic Tribes Southern Gaul Granted to Visigoths in 418 Task of Defending Western Roman Empire in the Hands of Germanic Generals The End of the Western Empire Odoacer - Leader of Ostrogothic Foederati (470) Romulus Augustus, Last Roman Emperor in the West Odoacer Attacks and Defeats Romulus Augustus Declares Himself First King of Italy (476) The Germanic Kingdoms Map Continuity with Rome Germans Admired and Wanted to Share in the Wealth and Civilization of Rome 3 Theodoric (454-526) Two-Tiered Government Similar Experiments Tried in Burgundian Kingdom Discontinuity Urban vs. Rural Germanic People Are Primarily Rural Germanic Manors and Villages Dissolution of Roman Cities Rule of Law vs. Personal Justice Rome: Extensive Law Code, Court System, Standards for Evidence, Advocates Germans: Blood Feuds, Trial by Ordeal Tribe vs. State New Opportunities Emergence of the Church Pope Gregory the Great (590-604) Latin Christendom . -

Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department Of

Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of History TOWARDS THE END OF AN EMPIRE: ROME IN THE WEST AND ATTILA (425-455 AD) Tunç Türel Master’s Thesis Ankara, 2016 TOWARDS THE END OF AN EMPIRE: ROME IN THE WEST AND ATTILA (425-455 AD) Tunç Türel Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of History Master’s Thesis Ankara, 2016 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study would have been impossible to finish without the support of my family. Therefore, I give my deepest thanks and love to my mother, without whose warnings my eyesight would have no doubt deteriorated irrevocably due to extensive periods of reading and writing; to my sister, who always knew how to cheer me up when I felt most distressed; to my father, who did not refrain his support even though there are thousands of km between us and to Rita, whose memory still continues to live in my heart. As this thesis was written in Ankara (Ancyra) between August-November 2016, I also must offer my gratitudes to this once Roman city, for its idyllic park “Seğmenler” and its trees and birds offered their much needed comfort when I struggled with making sense of fragmentary late antique chronicles and for it also houses the British Institute at Ankara, of which invaluable library helped me find some books that I was unable to find anywhere else in Ankara. I also thank all members of www.romanarmytalk.com, as I have learned much from their discussions and Gabe Moss from Ancient World Mapping Center for giving me permission to use two beautifully drawn maps in my work. -

Chapter Thirteen New Covenant and Other Christianities, to Ca. 185 CE

Chapter Thirteen New Covenant and Other Christianities, to ca. 185 CE The disastrous revolt of 66-70 marks a sharp turning point in the history of both Judaism and Christianity. The militancy of the first Christiani did not survive the disaster (that an oracle ordered “the Christians” to flee from Jerusalem to Pella just before the war of 66-70 is a much later invention).1 Two very different directions taken in the generation after the destruction of the Jerusalem temple led to the dramatic growth of two distinct religions: New Covenant Christianity and rabbinic Judaism. Although they had a common heritage these two religions differed widely not only from each other but also from the religion of Judaea during the Second Temple period. Rabbinic Judaism devoted itself fervently to the torah, in the belief that Adonai had punished Judaea because its people had been too lax in following his law. New Covenant Christians, contrarily, believed that God had ordained the destruction of the temple to make way for the parousia of Jesus the Christ and the End of Time. That religiosity and superstitious fanaticism were the cause of the disaster did not occur to either camp. A small minority of Judaeans, however, followed a third course in the aftermath of 70: these people gave up entirely on Adonai, his covenants, and the temporal world, and formulated - on the authority, they claimed, of Jesus the Christ - a mythical explanation of reality that scholars call “Gnosticism.” Although we have more information about each of the three new movements than about traditional Judaism in the Greek-speaking Diaspora, it must be added that for a very long time after 70 CE the majority of Judaeans did not adhere to any one of the three.