Exit, in Flames 08

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

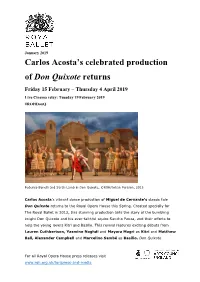

Don Quixote Press Release 2019

January 2019 Carlos Acosta’s celebrated production of Don Quixote returns Friday 15 February – Thursday 4 April 2019 Live Cinema relay: Tuesday 19 February 2019 #ROHDonQ Federico Bonelli and Sarah Lamb in Don Quixote, ©ROH/Johan Persson, 2013 Carlos Acosta’s vibrant dance production of Miguel de Cervante’s classic tale Don Quixote returns to the Royal Opera House this Spring. Created specially for The Royal Ballet in 2013, this stunning production tells the story of the bumbling knight Don Quixote and his ever-faithful squire Sancho Panza, and their efforts to help the young lovers Kitri and Basilio. This revival features exciting debuts from Lauren Cuthbertson, Yasmine Naghdi and Mayara Magri as Kitri and Matthew Ball, Alexander Campbell and Marcelino Sambé as Basilio. Don Quixote For all Royal Opera House press releases visit www.roh.org.uk/for/press-and-media includes a number of spectacular solos and pas de deux as well as outlandish comedy and romance as the dashing Basilio steals the heart of the beautiful Kitri. Don Quixote will be live streamed to cinemas on Tuesday 19 February as part of the ROH Live Cinema Season. Carlos Acosta previously danced the role of Basilio in many productions of Don Quixote. He was invited by Kevin O’Hare Director of The Royal Ballet, to re-stage this much-loved classic in 2013. Acosta’s vibrant production evokes sunny Spain with designs by Tim Hatley who has also created productions for the National Theatre and for musicals including Dreamgirls, The Bodyguard and Shrek. Acosta’s choreography draws on Marius Petipa’s 1869 production of this classic ballet and is set to an exuberant score by Ludwig Minkus arranged and orchestrated by Martin Yates. -

RELEASE DATE SEPTEMBET 2020 Essential Royal Ballet

RELEASE DATE SEPTEMBET 2020 Essential Royal Ballet The Royal Ballet Delve into the archive of The Royal Ballet in this special collection full of clips and interviews Katie Derham introduces highlights from the past ten years at the Royal Ballet in this special, extended edition of Essential Royal Ballet. Presented on location in Covent Garden at the iconic Royal Opera House, Katie weaves the history of ballet through carefully curated excerpts from the past decade of performances and goes behind the scenes to see what it takes to be a dancer in the company of The Royal Ballet as they prepare to take to the stage. From the great classics of The Sleeping Beauty and The Nutcracker to the exciting frontiers of contemporary dance, Katie takes us on a romp through the repertory, showcasing the diversity of the UK’s biggest ballet company. With stunning solos, passionate pas de deux and jaw-dropping numbers for the corps de ballet, it is a chance to see your favourite dancers up close, including Carlos Acosta, Marianela Nuñez, Natalia Osipova and Steven McRae, alongside rising stars like Francesca Hayward and Matthew Ball, who will introduce their favourite ballets and share stories of their life on the stage. The ballets featured include the classics Giselle, La Bayadère, Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty and The Nutcracker while the 20th-century heritage of the Royal Ballet is explored in works by Frederick Ashton and Kenneth MacMillan. The contemporary life of the company is showcased in works by Christopher Wheeldon, and Wayne McGregor, along side recent productions of classic works. -

The Royal Ballet Present Romeo and Juliet, Kenneth Macmillan's

February 2019 The Royal Ballet present Romeo and Juliet, Kenneth MacMillan’s dramatic masterpiece at the Royal Opera House Tuesday 26 March – Tuesday 11 June 2019 | roh.org.uk | #ROHromeo Matthew Ball and Yasmine Naghdi in Romeo and Juliet. © ROH, 2015. Photographed by Alice Pennefather Revival features a host of debuts from across the Company, including Akane Takada, Beatriz Stix-Brunell, Anna Rose O’Sullivan, William Bracewell, Marcelino Sambé and Reece Clarke. Principal dancer with American Ballet Theater, David Hallberg makes his debut in this production as Romeo opposite Natalia Osipova as Juliet. Production relayed live to cinemas and on Tuesday 11 June 2019. This Spring, The Royal Ballet revives Kenneth MacMillan’s 20th-century dramatic masterpiece, Romeo and Juliet. Set to Sergey Prokofiev’s seminal score, the ballet contrasts romantic pas de deux with a series For all Royal Opera House press releases visit www.roh.org.uk/for/press-and-media of vibrant ensemble scenes, set against the backdrop of 16th-century Verona as evoked by Nicholas Georgiadis’s designs. A work which has been performed by The Royal Ballet more than 400 times since it was premiered at Covent Garden in 1965, Romeo and Juliet is a classic of the 20th-century ballet repertory, and showcases the dramatic ability of the Company, as well as incorporating a plethora of MacMillan’s signature challenging choreography. During the course of this revival, Akane Takada, Beatriz Stix-Brunell and Anna Rose O’Sullivan debut as Juliet. Also performing the role during this run are Principal dancers Francesca Hayward, Sarah Lamb and Marianela Nuñez. -

The Mariinsky Ballet & Orchestra

Thursday, October 1, 2015, 8pm Friday, October 2, 2015, 8pm Saturday, October 3, 2015, 2pm & 8pm Sunday, October 4, 2015, 3pm Zellerbach Hall The Mariinsky Ballet & Orchestra Gavriel Heine, Conductor The Company Diana Vishneva, Nadezhda Batoeva, Anastasia Matvienko, Sofia Gumerova, Ekaterina Chebykina, Kristina Shapran, Elena Bazhenova Vladimir Shklyarov, Konstantin Zverev, Yury Smekalov, Filipp Stepin, Islom Baimuradov, Andrey Yakovlev, Soslan Kulaev, Dmitry Pukhachov Alexandra Somova, Ekaterina Ivannikova, Tamara Gimadieva, Sofia Ivanova-Soblikova, Irina Prokofieva, Anastasia Zaklinskaya, Yuliana Chereshkevich, Lubov Kozharskaya, Yulia Kobzar, Viktoria Brileva, Alisa Krasovskaya, Marina Teterina, Darina Zarubskaya, Olga Gromova, Margarita Frolova, Anna Tolmacheva, Anastasiya Sogrina, Yana Yaschenko, Maria Lebedeva, Alisa Petrenko, Elizaveta Antonova, Alisa Boyarko, Daria Ustyuzhanina, Alexandra Dementieva, Olga Belik, Anastasia Petushkova, Anastasia Mikheikina, Olga Minina, Ksenia Tagunova, Yana Tikhonova, Elena Androsova, Svetlana Ivanova, Ksenia Dubrovina, Ksenia Ostreikovskaya, Diana Smirnova, Renata Shakirova, Alisa Rusina, Ekaterina Krasyuk, Svetlana Russkikh, Irina Tolchilschikova Alexey Popov, Maxim Petrov, Roman Belyakov, Vasily Tkachenko, Andrey Soloviev, Konstantin Ivkin, Alexander Beloborodov, Viktor Litvinenko, Andrey Arseniev, Alexey Atamanov, Nail Enikeev, Vitaly Amelishko, Nikita Lyaschenko, Daniil Lopatin, Yaroslav Baibordin, Evgeny Konovalov, Dmitry Sharapov, Vadim Belyaev, Oleg Demchenko, Alexey Kuzmin, Anatoly Marchenko, -

An Evening with Natalia Osipova Valse Triste, Qutb & Ave Maria

Friday 24 April Sadler’s Wells Digital Stage An Evening with Natalia Osipova Valse Triste, Qutb & Ave Maria Natalia Osipova is a major star in the dance world. She started formal ballet training at age 8, joining the Bolshoi Ballet at age 18 and dancing many of the art form’s biggest roles. After leaving the Bolshoi in 2011, she joined American Ballet Theatre as a guest dancer and later the Mikhailovsky Ballet. She joined The Royal Ballet as a principal in 2013 after her guest appearance in Swan Lake. This showcase comprises of three of Natalia’s most captivating appearances on the Sadler’s Wells stage. Featuring Valse Triste, specially created for Natalia and American Ballet Theatre principal David Hallberg by Alexei Ratmansky, and the beautifully emotive Ave Maria by Japanese choreographer Yuka Oishi set to the music of Schubert, both of which premiered in 2018 at Sadler’s Wells’ as part of Pure Dance. The programme will also feature Qutb, a uniquely complex and intimate work by Sadler’s Wells Associate Artist Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, which premiered in 2016 as part of Natalia’s first commission alongside works by Arthur Pita and fellow Associate Artist Russell Maliphant. VALSE TRISTE, PURE DANCE 2018 Natalia Osipova Russian dancer Natalia Osipova is a Principal of The Royal Ballet. She joined the Company as a Principal in autumn 2013, after appearing as a Guest Artist the previous Season as Odette/Odile (Swan Lake) with Carlos Acosta. Her roles with the Company include Giselle, Kitri (Don Quixote), Sugar Plum Fairy (The Nutcracker), Princess Aurora (The Sleeping Beauty), Lise (La Fille mal gardée), Titania (The Dream), Marguerite (Marguerite and Armand), Juliet, Tatiana (Onegin), Manon, Sylvia, Mary Vetsera (Mayerling), Natalia Petrovna (A Month in the Country), Anastasia, Gamzatti and Nikiya (La Bayadère) and roles in Rhapsody, Serenade, Raymonda Act III, DGV: Danse à grande vitesse and Tchaikovsky Pas de deux. -

Throw Together a Night of Performances by International

Throw together a night of performances by international dancers, sprinkle in some teenage competition winners’ solos, and call it something cute: That would seem to be the recipe for Youth America Grand Prix’s “Stars of Today Meet the Stars of Tomorrow” gala, happening this Thursday and Friday at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Except, the name of this annual program is eerily prescient. When you look back at the lists of YAGP medalists from the past 15 years, that “Stars of Tomorrow” moniker is spot-on. They read like something of a Who’s Who of ballet—including several top names who’ve been highlighted in Dance Magazine. Back in 2002, Sarah Lane nabbed the senior bronze medal with an unforgettable performance: After her music stopped 20 seconds into her Paquita variation, she finished the rest in silence. In the audience (which erupted into a spontaneous standing ovation) was American Ballet Theatre artistic director Kevin McKenzie. We ended up putting Lane onDance Magazine‘s cover in June 2007 just before he promoted her to soloist. Jim Nowakowski won the Youth Grand Prix in 2002 before joining Houston Ballet, then took a star turn on “So You Think You Can Dance.” We named him one of Dance Magazine‘s “25 to Watch” this year. That same year, Brooklyn Mack placed third in the classical dance category for senior men. Today, he’s a standout dancer at The Washington Ballet, and partnered Misty Copeland in her first U.S. performance of Swan Lake. Hee Seo took the Grand Prix in 2003. -

Premieres on the Cover People

PDL_REGISTRATION_210x297_2017_Mise en page 1 01.06.17 10:52 Page1 Premieres 18 Bertaud, Valastro, Bouché, BE PART OF Paul FRANÇOIS FARGUE weighs up four new THIS UNIQUE ballets by four Paris Opera dancers EXPERIENCE! 22 The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas MIKE DIXON considers Daniel de Andrade's take on John Boyne's wartime novel 34 Swan Lake DEBORAH WEISS on Krzysztof Pastor's new production that marries a slice of history with Reece Clarke. Photo: Emma Kauldhar the traditional story P RIX 38 Ballet of Difference On the Cover ALISON KENT appraises Richard Siegal's new 56 venture and catches other highlights at Dance INTERNATIONAL BALLET COMPETITION 2017 in Munich 10 Ashton JAN. 28 TH – FEB. 4TH, 2018 AMANDA JENNINGS reviews The Royal DE Ballet's last programme in London this Whipped Cream 42 season AMANDA JENNINGS savours the New York premiere of ABT's sweet confection People L A U S ANNE 58 Dangerous Liaisons ROBERT PENMAN reviews Cathy Marston's 16 Zenaida's Farewell new ballet in Copenhagen MIKE DIXON catches the live relay from the Royal Opera House 66 Odessa/The Decalogue TRINA MANNINO considers world premieres 28 Reece Clarke by Alexei Ratmansky and Justin Peck EMMA KAULDHAR meets up with The Royal Ballet’s Scottish first artist dancing 70 Preljocaj & Pite principal roles MIKE DIXON appraises Scottish Ballet's bill at Sadler's Wells 49 Bethany Kingsley-Garner GERARD DAVIS catches up with the Consort and Dream in Oakland 84 Scottish Ballet principal dancer CARLA ESCODA catches a world premiere and Graham Lustig’s take on the Bard’s play 69 Obituary Sergei Vikharev remembered 6 ENTRE NOUS Passing on the Flame: 83 AUDITIONS AND JOBS 78 Luca Masala 101 WHAT’S ON AMANDA JENNINGS meets the REGISTRATION DEADLINE contents 106 PEOPLE PAGE director of Academie de Danse Princesse Grace in Monaco Front cover: The Royal Ballet - Zenaida Yanowsky and Roberto Bolle in Ashton's Marguerite and Armand. -

Gp 3.Qxt 7/14/17 2:07 PM Page 1 Page 4

07-26 Taming Shrew v9.qxp_Gp 3.qxt 7/14/17 2:07 PM Page 1 Page 4 Lincoln Center Festival lead support is provided by American Express July 26–30 David H. Koch Theater Bolshoi Ballet Ballet Director Makhar Vaziev The Taming of the Shrew Ballet in two acts Choreography Jean-Christophe Maillot Music Dmitri Shostakovich Set Design Ernest Pignon-Ernest Costume Design Augustin Maillot Lighting and Video Projection Design Dominique Drillot New York City Ballet Orchestra Conductor Igor Dronov Approximate running time: 1 hours and 55 minutes, with one intermission This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Made possible in part by The Harkness Foundation for Dance. Endowment support for the Lincoln Center Festival 2017 presentation of The Taming of the Shrew is provided by Blavatnik Family Foundation Fund for Dance. Public support for Festival 2017 is provided by the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs and New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. The Bolshoi Theatre gratefully acknowledges the support of its General Sponsor, Credit Suisse. 07-26 Taming Shrew.qxp_Gp 3.qxt 7/18/17 12:10 PM Page 2 LINCOLN CENTER FESTIVAL 2017 THE TAMING OF THE SHREW Wednesday, July 26, 2017, at 7:30 p.m. The Taming of the Shrew Katharina: Ekaterina Krysanova Petruchio: Vladislav Lantratov Bianca: Olga Smirnova Lucentio: Semyon Chudin Hortensio: Igor Tsvirko Gremio: Vyacheslav Lopatin The Widow: Yulia Grebenshchikova Baptista: Artemy Belyakov The Housekeeper: Yanina Parienko Grumio: Georgy Gusev MAIDSERVANTS Ana Turazashvili, Daria Bochkova, Anastasia Gubanova, Victoria Litvinova, Angelina Karpova, Daria Khokhlova SERVANTS Alexei Matrakhov, Dmitry Dorokhov, Batyr Annadurdyev, Dmitri Zhuk, Maxim Surov, Anton Savichev There will be one intermission. -

American Ballet Theatre Returns to New York City Center for Digital Program Filmed Live on Stage

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: American Ballet Theatre returns to New York City Center for digital program filmed live on stage Four works by ABT Artist in Residence Alexei Ratmansky; including a World Premiere created in a “ballet bubble” Available on demand March 23 – April 18 $25 Digital Access on sale March 1 at noon Patrick Frenette, Skylar Brandt, and Tyler Maloney in Bernstein in a Bubble. Photo by Christopher Duggan Photography February 26, 2021 (New York, NY) – New York City Center President & CEO Arlene Shuler today announced a new digital program, ABT Live from City Center | A Ratmansky Celebration, featuring American Ballet Theatre (ABT) premiering Tuesday, March 23 at 7 PM, and available on demand through Sunday, April 18. Filmed live on the City Center stage, the program marks ABT’s much anticipated return to the historic theater for their first full evening program at City Center since 2012. Co-presented by American Ballet Theatre and New York City Center, the program will feature many of the company’s renowned dancers in works by acclaimed choreographer and ABT Artist in Residence Alexei Ratmansky. Hosted by author and American Ballet Theatre Co-Chair of the Trustees Emeriti Susan Fales-Hill, highlights include excerpts from The Seasons (2019), Seven Sonatas (2009), and The Sleeping Beauty (2015), and Bernstein in a Bubble, a World Premiere set to the music of legendary composer Leonard Bernstein. The new work, Ratmansky’s first since March 2020, was created in January and February of this year during a quarantined “ballet bubble” in Silver Bay, New York. The program features ABT dancers Aran Bell, Isabella Boylston, Skylar Brandt, Herman Cornejo, Patrick Frenette, Carlos Gonzalez, Blaine Hoven, Catherine Hurlin, Tyler Maloney, Luciana Paris, Devon Teuscher, Cassandra Trenary, and James Whiteside. -

World Ballet Day 2014

GLOBAL FIRST: FIVE WORLD-CLASS BALLET COMPANIES, ONE DAY OF LIVE STREAMING ON WEDNESDAY 1 OCTOBER www.roh.org.uk/worldballetday The A u str a lia n B a llet | B o lsho i B a llet | The R o y a l B a llet | The N a tio n a l B a llet o f C a n a d a | S a n F r a n c isc o B a llet T h e first ev er W o r ld B a llet D a y w ill see an u n p rec ed en ted c ollab oration b etw een fiv e of th e w orld ‘s lead in g b allet c om p an ies. T h is on lin e ev en t w ill tak e p lac e on W ed n esd ay 1 O c tob er w h en eac h of th e c om p an ies w ill stream liv e b eh in d th e sc en es ac tion from th eir reh earsal stu d ios. S tartin g at th e b egin n in g of th e d an c ers‘ d ay , eac h of th e fiv e b allet c om p an ies œ The A u str a lia n B a llet, B o lsho i B a llet, The R o y a l B a llet, The N a tio n a l B a llet o f C a n a d a an d S a n F r a n c isc o B a llet œ w ill tak e th e lead for a fou r h ou r p eriod stream in g liv e from th eir h ead q u arters startin g w ith th e A u stralian B allet in M elb ou rn e. -

The Bolshoi Ballet Sets the Stage Ablaze with 'The Flames of Paris

MEDIA ALERT – February 12, 2018 The Bolshoi Ballet Sets the Stage Ablaze With ‘The Flames of Paris,’ Presented Exclusively in U.S. Cinemas on Sunday, March 4 Only WHAT: The world-renowned dance company Bolshoi Ballet is “on blistering form” (The Telegraph) in their performance of “The Flames of Paris,” hitting big screens nationwide on Sunday, March 4 for a one-day event. Captured live from Moscow’s legendary Bolshoi Theatre earlier that same day, the production is part of the 2017-18 Bolshoi Ballet in Cinema Series, presented by Fathom Events in partnership with BY Experience and Pathé Live. Very few ballets can properly depict the Bolshoi’s overflowing energy and fiery passion as can Alexei Ratmansky’s captivating revival of “The Flames of Paris,” set in the era of the French Revolution. With powerful virtuosity and some of the most stunning pas de deux, the Bolshoi Ballet displays an exuberance well-suited for the Moscow stage. WHO: Fathom Events, BY Experience and Pathé Live WHEN: Sunday, March 4 2018; 12:55 p.m.ET / 11:55 a.m. CT / 10:55 a.m.MT & 12:55 p.m. PT, HI, AK (pre-recorded playback) WHERE: Tickets for Bolshoi’s “The Flames of Paris” can be purchased online by visiting www.FathomEvents.com or at participating theater box offices. Fans throughout the U.S. will be able to enjoy the event in more than 350 select movie theaters through Fathom’s Digital Broadcast Network (DBN). For a complete list of theater locations visit the Fathom Events website (theaters and participants are subject to change). -

Press Information → 2020/21 Season

Press Information → 2020/21 Season THE VIENNA ① STATE BALLET 2020/21 »Along with my team and my dancers, I intend to work towards developing the Vienna State Ballet into a major hotspot of the art of dance in Austria and Europe forming an ensemble that reflects and inspires the traditions, changes and innovations of the lively metropolis, city of art and music, Vienna.« Martin Schläpfer Martin Schläpfer takes over the direction of the Vienna State Ballet with the 2020 / 21 season. The renowned Swiss choreographer and ballet director has recently led the multi-award-winning Ballett am Rhein Düsseldorf Duisburg to international acclaim. His works fascinate with their intensity, their virtuosity, their deeply moving images and a concise language of movement, which is understood as making music with the body, but always reflects the atmosphere and questions of today’s world. Several performances offer the opportunity to encounter Martin Schläpfer’s art – including two world premieres: Two new pieces for Vienna are being created to Gustav Mahler’s 4th Symphony and Dmitri Shostakovich’s 15th Symphony, which also mark the beginning of the intensive creative dialogue that Martin Schläpfer will be establishing with the artists of his ensemble in the coming years. As director, Martin Schläpfer is a bridge-builder who will naturally continue to cultivate the great ballet traditions, but will also enrich the programme with important contemporary artists and a great variety of choreographic signatures. The masters of American neo-classical ballet George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins will continue to be among the fixed stars of the Vienna repertoire, as will the Dutchman Hans van Manen.