Hull Development Framework

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplementary Planning Document (SPD) 10

Supplementary Planning Document (SPD) 10 Trees Adopted 7 January 2019 1 1. Introduction / summary 1.1 This Supplementary Planning Document (SPD) acts as guidance to policies in the Hull Local Plan 2016 to 2032, adopted in November 2017. The Local Plan is a 16 year document which sets out the vision for growth in Hull. It identifies the quantity and location for new housing, community facilities, shops and employment provision. 1.2 This document provides planning guidance on Policy 45 – ‘Trees’. It gives advice as to how future planting of trees and tree protection should be addressed via the planning process and the considerations that need to be taken into account before, during and after development. 1.3 Local Plan policy seeks to promote an increase in the provision and diversity of green infrastructure, particularly tree and woodland provision, for its benefits in urban cooling, health and well-being, and conserving and enhancing biodiversity. 1.4 The Supplementary Planning Document seeks to: • Provide clarity to developers, statutory consultees, local residents and other stakeholders; • Outline the national and local planning policy context that guides how trees should be considered in development. • Outline the broad benefits of trees and woodland to the city. • Explain what role trees have in contributing to the distinctive character of areas within the city ; • Explain how new planting of trees should be incorporated into future development, either on site or where this is not possible where future planting should be directed. This includes how planting can be directed to achieve objectives of increasing biodiversity and to support flood risk mitigation. -

Make It Happen Prospectus 2020/2021 Wyke Sixth Form College 2020/2021 Prospectus Wyke Sixth Form College 2020/2021 Prospectus

MAKE IT HAPPEN PROSPECTUS 2020/2021 WYKE SIXTH FORM COLLEGE 2020/2021 PROSPECTUS WYKE SIXTH FORM COLLEGE 2020/2021 PROSPECTUS EXTENDED PROJECT QUALIFICATION WELCOME COURSE Extended Project Qualification (EPQ) 34 TO WYKE ENGLISH INDEX English Literature 35 “WYKE OFFERS A TRUE ‘SIXTH FORM’ EXPERIENCE WITH English Language 35 HIGH QUALITY SPECIALIST TEACHING, A UNIVERSITY STYLE BUSINESS and FINANCE MODERN FOREIGN LANGUAGES CAMPUS, A CULTURE THAT FOSTERS INDEPENDENCE, Accounting 22 German 36 ENCOURAGING STUDENTS TO BE THEMSELVES. Economics 22 French 37 As the largest A Level provider in Hull and East Riding, the Spanish 37 statistics are straightforward; students do very well at Wyke Business A Level 23 Sixth Form College, with our results justifying the position in Business BTEC 23 HUMANITIES the top 15% of all Sixth Form providers nationally. VISUAL ARTS History 38 In 2019, our pass rate percentage at A Level was 99.7%, with Government and Politics 38 the BTEC pass rate at 100%. This includes 315 of the top A* Fine Art 24 and A grades, 53% of the cohort achieving A*- B grades and Photography 24 Geography 39 a remarkable 82% achieving A*-C grades. Our BTEC pass rate was 100%, with 80 students achieving 3 Distinction*, Graphic Design 25 HEALTH and SOCIAL CARE the equivalent to three A*s at A Level, in comparison to 57 Art and Design Foundation Diploma 25 Health and Social Care 41 students in 2018. SCIENCES COMPUTING Our students have progressed to exceptional destinations with 10 students advancing to Oxbridge and 24 taking up Biology 26 IT and Computing 43 places on Medicine, Dentistry or Veterinary courses over the Chemistry 26 past 3 years. -

Passionate for Hull

Drypool Parish, Hull October 2015 WANTED Drypool Team Rector / Vicar of St Columba’s Passionate for Hull Parish Profile for the Team Parish of Drypool, Hull 1/30 Drypool Parish, Hull October 2015 Thank you for taking the time to view our Parish profile. We hope that it will help you to learn about our community of faith and our home community; about our vision for the future, and how you might take a leading role in developing and taking forward that vision. If you would like to know more, or visit the Parish on an informal basis, then please contact any one of the following Revd Martyn Westby, Drypool Team Vicar, with special responsibility for St John’s T. 01482 781090, E. [email protected] Canon Richard Liversedge, Vice-chair of PCC & Parish Representative T. 01482 588357, E. [email protected] Mrs Liz Harrison Churchwarden, St Columba’s T. 01482 797110 E. [email protected] Mr John Saunderson Churchwarden, St Columba’s & Parish Representative T. 01482 784774 E. [email protected] 2/30 Drypool Parish, Hull October 2015 General statement of the qualities and attributes that the PCC would wish to see in a new Incumbent We are praying and looking for a priest to join us as Rector of Drypool Team Parish and vicar of St Columba’s Church. We seek someone to lead us on in our mission to grow the Kingdom of God in our community, and these are the qualities we are looking for. As Team Rector The ability to: Embrace a call to urban ministry and a desire to develop a pastoral heart for the people of the various communities in the Parish Be Strategic and Visionary Work in partnership with existing Team Vicar and Lay Leadership Developing and empowering Lay Leadership further Respect the uniqueness of each congregation and continue unlocking the sharing of each others strengths Be organised and promote good organisation and communication Someone who can grow to love this community as we love it. -

Highway Winter Service Plan

KINGSTON UPON HULL CITY COUNCIL HIGHWAY WINTER SERVICE PLAN (FOR THE ADOPTED HIGHWAY NETWORK) Kingston House Bond Street, Kingston upon Hull, HU1 3ER. Updated September 2011 Updated September 2012 Updated September 2013 Last Updated October 2014 NOT A CONTROLLED DOCUMENT IF PRINTED Highway Winter Service HIGHWAY WINTER SERVICE PLAN CONTENTS Page Part Title 2 Contents 4 Introduction Section A Statement of Policies and Responsibilities 6 Part 1 Policies and objectives – Statement of Service 7 Part 2 Client and contractor risks and responsibilities 10 Part 3 Partnership or shared risks and responsibilities 10 Part 4 Decision making processes 20 Part 5 Liaison arrangements with other authorities 22 Part 6 Winter risk period 23 Part 7 Reciprocal Agreement with the East Riding of Yorkshire Council Section B Quality Plan 25 Part 1 Quality management regime 25 Part 2 Document control procedures 25 Part 3 Circulation of documents 26 Part 4 Information recording and analysis 27 Part 5 Arrangements for performance monitoring, audit and updating Section C Route Planning for Carriageways, Footways & Cycle Routes 29 Part 1 General 29 Part 2 Carriageway routes for precautionary treatment 38 Part 3 Carriageway routes for post treatment by risk level 43 Part 4 Carriageway routes for snow clearance by risk level 46 Part 5 Routes for footbridges, subways and other high risk pedestrian areas 47 Part 6 Routes for other footway treatment by risk level 55 Part 7 Routes for cycle route treatment by risk level 56 Part 8 Response and treatment times for all carriageway -

Humber Area Local Aggregate Assessment

OCTOBER 2019 (Data up to 2018) HUMBER AREA LOCAL AGGREGATE ASSESSMENT CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 1. INTRODUCTION 3 Development Plans 4 Spatial Context 5 Environmental Constraints & Opportunities 6 2. GEOLOGY & AGGREGATE RESOURCES 8 Bedrock Geology 8 Superficial Geology 9 Aggregate Resources 10 Sand and Gravel 10 Chalk & Limestone 11 Ironstone 11 3. ASSESSMENT OF SUPPLY AND DEMAND 12 Sand & Gravel 12 Crushed Rock 14 4. AGGREGATE CONSUMPTION & MOVEMENTS 16 Consumption 16 Imports & Exports 18 Recycled & Secondary Aggregates 19 Marine Aggregates 23 Minerals Infrastructure 25 6. FUTURE AGGREGATE SUPPLY AND DEMAND 28 Managed Aggregate Supply System (MASS) 28 Approaches to Identifying Future Requirement 29 Potential Future Requirements 34 7 CONCLUSION 36 Monitoring and Reviewing the Local Aggregates Assessment 37 Consideration by the Yorkshire and Humber Aggregates Working Party 37 APPENDIX 1: YHAWP CONSULTATION RESPONSES TO A DRAFT VERSION OF THIS LAA, THE COUNCILS’ RESPONSE, AND ANY AMENDMENTS TO THE DOCUMENT AS A RESULT. 41 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The requirement to produce an annual Local Aggregate Assessment (LAA) was introduced through the publication of the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) in March 2012 and is still a requirement set out in the revised NPPF (2019). The Government issued further guidance on planning for minerals in the National Planning Practice Guidance (NPPG), incorporating previous guidance on the Managed Aggregate Supply System (MASS). This report is the sixth LAA that aims to meet the requirements set out in both of these documents. It is based on sales information data covering the calendar years up to 2018. Landbank data is 2018-based. Sales and land bank information is sourced from annual surveys of aggregate producers in the Humber area (East Riding of Yorkshire, Kingston upon Hull, North East Lincolnshire & North Lincolnshire), alongside data from the Yorkshire & Humber Aggregates Working Party Annual Monitoring Reports, planning applications, the Crown Estate, and the Environment Agency. -

Hull Core Strategy - Contacts List (As at July 2011)

Hull Core Strategy - Contacts List (as at July 2011) Introduction This report provides details about the contacts made during the development of the Hull Core Strategy. It includes contact made at each plan making stage, as follows: • Issues and Options – August 2008 • Emerging Preferred Approach – February 2010 • Core Strategy Questionnaire – September 2010 • Spatial Options – February 2011 • Core Strategy Publication Version – July 2011 A list of Hull Development Forum members (as at July 2011) is also enclosed. This group has met over 15 times, usually on a quarterly basis. The report also sets out the specific and general organisations and bodies that have been contacted, in conformity with the Council’s adopted Statement of Community Involvement. Specific groups are indicated with an asterisk. Please note contacts will change over time. Issues and Options – August 2008 (Letter sent to Consultants/Agents) Your Ref: My Ref: PPI/KG/JP Contact: Mr Keith Griffiths «Title» «First_Name» «Surname» Tel: 01482 612389 «Job_Title» Fax: 01482 612382 Email: [email protected] «Org» th «Add1» Date: 4 August 2008 «Add2» «Add3» «Town» «Postcode» Dear Sir/Madam Hull Core Strategy - issues, options and suggested preferred option Please find enclosed the ‘Hull Core Strategy issues, options and suggested preferred option’ document for your consideration. Your views should be returned to us by the 5 September, 2008 by using the form provided. In particular, could you respond to the following key questions: 1. What do you think to the issues, objectives, options and suggested preferred option set out in the document? 2. How would you combine the options? 3. -

Bishop Burton College East Riding College Franklin College Grimsby

Academic Routes for Health and Social Care Roles (England) Role Entry Requirements Academic Training Provider(s) in Qualification(s) Humber, Coast and Vale Activity Worker GCSEs A-C in English Social care Bishop Burton College and Maths qualification such as a East Riding College Level 2 Diploma in Franklin College Health and Social Grimsby Institute Care (Desirable) Hull College Scarborough Technical College Selby College York College Assistant/Associate Certificated evidence Completed (or be University of Hull Practitioner of national level 3 working towards) a University of York study. level 5 qualification. Grimsby Institute 80 UCAS Tariff points Examples include: from a minimum of 2 A Levels (or Diploma of equivalent). Higher Education GCSE English (DipHe) Language and Maths Foundation grade C, or grade 4, or degree above or equivalent Higher National Level 2 Literacy and Diploma (HND) Numeracy or NVQ Level 5 qualifications are desirable. Employment in a health care environment and employer support to undertake this study are also required. Care Assistant No set entry Care Certificate. Delivered in-house by requirements. employer. Employers expect good literacy, numeracy and IT skills and may ask for GCSEs (or equivalent) in English and Maths. Care Coordinator No set entry Varies depending on Varies depending on requirements. individual employer individual employer Employers expect good requirements. requirements. Academic Routes for Health and Social Care Roles (England) Role Entry Requirements Academic Training Provider(s) in Qualification(s) Humber, Coast and Vale literacy, numeracy and IT skills and may ask for GCSEs (or equivalent) in English and Maths. Deputy General No set entry Varies depending on Varies depending on Manager requirements. -

CONTRACTOR DETAILS Local Architects

CONTRACTOR DETAILS Disclaimer: Hull City Council provides details of these traders without any warranty. Individuals must satisfy themselves that the trader hired carries out works of a sufficient standard. The Council accepts no responsibility for any works carried out by any of the above traders. Local Architects Piercy Design Robert High The Quaker Meeting Rooms, 2 Beverley Road 4 Percy Street, South Cave Hull Brough HU2 8HH East Yorkshire HU15 2AU Tel: 01482 326415 Email: [email protected] Tel: 01430 423369 Website: http://www.piercydesign.co.uk/ Robert Farrow Design Ingleby & Hobson 30-32 Northgate, 114 Holme Church Lane Hessle Beverley East Yorkshire East Yorkshire HU13 9AA HU17 0PY Tel: 01482 640699 Tel: 01482 868690 Salt Architects Francis Johnson & Partners 54 Lairgate 16 High Street Beverley Bridlington East Yorkshire East Yorkshire HU17 8EU YO16 4PT Tel: 01482 888102 Tel: 01262 674 043 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website:http://saltarchitects.co.uk/projects/co Website: http://www.francisjohnson- nservation/ architects.co.uk/ LNS Partnership Terry Litten Architectural Services 28 John Street 30 West End Road Hull Cottingham HU2 8DH East Yorkshire HU16 5PN Tel: 01482 320127 Email: [email protected] Tel: 01482 845272 Website: http://www.lnspartnership.co.uk/ James M. Murray Purcell UK Access Architecture Ltd 29 Marygate Stockbridge House, 15 Stockbridge Rd York Elloughton East Yorkshire East Yorkshire YO30 7WH HU15 1HW Tel: 01904 644001 Tel. 01482 667214 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website: www.purcelluk.com Website: http://access-architecture.com/ Disclaimer: Hull City Council provides details of these traders without any warranty. -

Fish-Trail-Leaflet Colour Logo V2.Indd

1 Anchovy – a small bony fi sh 18 Haddock – Nearby is the city’s only National Trust property, commonly found off the coast of Peru. Maister House, which contains a magnifi cent a well-known food staircase. (Open offi ce hours, Mon - Fri). 36 chromed bronzes. source belonging to A popular attraction on the river is Hull’s last side The trail begins with a school of anchovies outside the Cod family. winder trawler, the Arctic Corsair, a reminder of the the City Hall. Close by, Queen Victoria stands Carved in Black Belgian Marble. city’s past as one of the world’s biggest fi shing ports. proudly ‘on the throne’, and is surrounded by impressive buildings such as Hull City Hall and the Dominating this area is the Hull Marina on the 30 Electric Eel – so called because it Ferens Art Gallery. site of two former docks, the sparkling centrepiece forming an atmospheric backdrop for major events. stuns its prey with an electric volt. Carved in Derbyshire Grit Stone appropriately 2 – a crustacean characterised The shaded brickwork along the promenade indicates Lobster the route of the medieval walls. The old Hessle Gate located beside the electric sub station. by an enlarged pair of pincers. is marked out opposite Humber Street (the fruit 31 Sea Trout – a member of the Eight lobsters cut into Cornish slate. market). At the Haddock, ‘Blistering Barnacles’ is a reference from the adventures of Tin Tin. Salmon family, they enter the A quotation from Lewis Caroll’s ‘Alice in rivers from the sea to breed. -

A Moth for Amy Is an Amy Johnson Festival a Moth for Amy 40 APLE RD Project

THOMAS CLARKSON A1079 41 WA 9 42 WNE ROAD A Moth for Amy is an Amy Johnson Festival A Moth for Amy 40 APLE RD project. Amy was one of the most influential BARNST and inspirational women of the twentieth WA ROBSON century. She was the first woman to fly solo GREENWOOD AVENUE A Moth for Amy is an animal sculpture the original sculpture, from which Y GANSTEAD LANE GANSTEAD WA SUTTON PARK LANE GANSTEAD from England to Australia and set a string WELL RD trail with a dierence. our flutter of Moths has hatched. The ENDYKE LANE SUTTON ROAD Y GOLF COURSE of other records throughout her career. Our HOL 59 Moths, each measuring almost SHANNON RD 43 MAIN ROAD festival over the summer of 2016 celebrated Inspired by Amy Johnson’s de 1.5m across, have been decorated by LEADS ROAD Amy’s life, achievements and legacy on the Havilland Gipsy Moth plane, in which artists and community groups, making INGLEMIRE LANE 75th anniversary of her death. The festival BEVERLEY ROAD SAL she made her epic flight to Australia each Moth a unique work of art. The SUTTON ROAD TSHOUSE ROAD HULL ROAD aimed to raise awareness of Amy Johnson’s in 1930, a flutter of exotic giant moths designs are inspired by Amy Johnson’s achievements as an aviator, as an engineer has alighted on walls and plinths achievements, her flight to Australia UNIVERSITY and as a woman of her time, one of the first LEADS ROAD across Hull, East Yorkshire and beyond! and the era in which she lived. -

FOI 158-19 Data-Infographic-V2.Indd

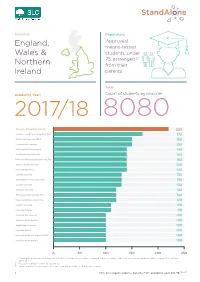

Domicile: Population: Approved, England, means-tested Wales & students, under 25, estranged [1] Northern from their Ireland parents Total: Academic Year: Count of students by provider 2017/18 8080 Manchester Metropolitan University 220 Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) 170 De Montfort University (DMU) 150 Leeds Beckett University 150 University Of Wolverhampton 140 Nottingham Trent University 140 University Of Central Lancashire (UCLAN) 140 Sheeld Hallam University 140 University Of Salford 140 Coventry University 130 Northumbria University Newcastle 130 Teesside University 130 Middlesex University 120 Birmingham City University (BCU) 120 University Of East London (UEL) 120 Kingston University 110 University Of Derby 110 University Of Portsmouth 100 University Of Hertfordshire 100 Anglia Ruskin University 100 University Of Kent 100 University Of West Of England (UWE) 100 University Of Westminster 100 0 50 100 150 200 250 1. “Estranged” means the customer has ticked the “You are irreconcilably estranged (have no contact with) from your parents and this will not change” box on their application. 2. Results rounded to nearest 10 customers 3. Where number of customers is less than 20 at any provider this has been shown as * 1 FOI | Estranged students data by HEP, academic year 201718 [158-19] Plymouth University 90 Bangor University 40 University Of Huddersfield 90 Aberystwyth University 40 University Of Hull 90 Aston University 40 University Of Brighton 90 University Of York 40 Staordshire University 80 Bath Spa University 40 Edge Hill -

INTERNAL POST Members Information INTERNAL POST

HUMBER BRIDGE Councillor L Redfern Councillor D Gemmell BOARD North Lincolnshire Council, Civic Kingston upon Hull City Council Centre Ashby Road Scunthorpe DN16 1AN Councillor S Parnaby OBE, Councillor C Shaw Lord C Haskins East Riding of Yorkshire Council North East Lincolnshire Council Quarryside Farm, County Hall Skidby, Beverley Cottingham, HU17 9BA East Yorkshire, HU16 5TG Mr S Martin Professor D Stephenson Mr J Butler Chief Executive, Clugston Clerk to the Humber Bridge 33 Hambling Drive Group Ltd Board Molescroft St Vincent House, Normanby Beverley Road, Scunthorpe HU17 9GD DN15 8QT Mr P Hill Mr P Dearing Anita Eckersley General Manager and Legal Services Committee Clerk to the Humber Bridgemaster Kingston upon Hull City Council Bridge Board Humber Bridge Administration Offices Ferriby Road, Hessle HU13 0JG Councillor Turner MBE, Other recipients for Mrs J Rae, Audit Commission Lincolnshire County Council information, Audit Commission c/o Hull City Council, Floor 2 Wilson Centre, Alfred Gelder Street, Hull HU1 2AG Nigel Pearson Simon Driver Shaun Walsh, Chief Executive Chief Executive Chief Executive East riding of Yorkshire Council North Lincolnshire Council North East Lincolnshire Council Civic Centre, Ashby Road Municipal Offices, Town Hall Scunthorpe Square, Grimsby DN16 1AN DN31 1HU INTERNAL POST INTERNAL POST Members Information Reference Library APPEALS COMMITTEE Councillor Abbott Councillor Conner Councillor P D Clark INTERNAL MAIL INTERNAL MAIL G Paddock K Bowen Neighbourhood Nuisance Team Neighbourhood Nuisance Team HAND