S' =.; § Co C • N(D O ::L O-, ~

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project (INREMP)

Environmental and Social Monitoring Report Semi-annual Report July 2018 PHI: Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project (INREMP) Reporting period: July to December 2016 Prepared by Department of Environment and Natural Resources - Forest Management Bureau for the Asian Development Bank This Semi-annual Environmental and Social Monitoring Report is a document of the Borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB Board of Directors, Management or staff, and my be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as the legal or other status of any territory or area. ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank ADSDPP Ancestral Domain sustainable Development and Protection Plan BURB Bukidnon Upper River Basin CENRO Community Environment and Natural Resource Office CP Certificate of Precondition CURB Chico Upper River Basin DED Detailed engineering Design DENR Department of Environment and Natural Resources FMB Forest Management Bureau GAP Gender Action Plan GOP Government of the Philippines GRM Grievance Redress Mechanism EA Executing Agency IEE Initial Environmental Examination IFAD International Fund for Agricultural Development INREMP Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project IP Indigenous People IPDP Indigenous Peoples Development Plan IPP Indigenous -

The-Revenue-Code-Of-Malaybalay

Republic of the Philippines Province of Bukidnon City of Malaybalay * * * Office of the Sangguniang Panlungsod EXCERPT FROM THE MINUTES OF THE 19TH REGULAR SESSION FOR CY 2016 OF THE 7TH SANGGUNIANG PANLUNGSOD OF THE CITY OF MALAYBALAY, BUKIDNON HELD AT THE SP SESSION HALL ON NOVEMBER 29, 2016. PRESENT: Hon. City Councilor Jay Warren R. Pabillaran Hon. City Councilor Lorenzo L. Dinlayan, Jr. Hon. City Councilor Hollis C. Monsanto Hon. City Councilor Rendon P. Sangalang Hon. City Councilor George D. Damasco, Sr. Hon. City Councilor Jaime P. Gellor, Jr., Temporary Presiding Officer Hon. City Councilor Louel M. Tortola Hon. City Councilor Nicolas C. Jurolan Hon. City Councilor Manuel M. Evangelista, Sr. ABSENT: Hon. City Vice Mayor Roland F. Deticio (Official Business) Hon. City Councilor Anthony Canuto G. Barroso (Official Business) Hon. City Councilor Provo B. Antipasado, Jr. (Official Business) Hon. City Councilor Bede Blaise S. Omao (Official Business) --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ORDINANCE NO. 880 Series of 2016 Sponsored by the Committee on Ways and Means Chairman - Hon. Hollis C. Monsanto Members - Hon. Jaime P. Gellor, Jr. - Hon. Louel M. Tortola Chapter One GENERAL PROVISIONS Article 1 TITLE, SCOPE AND DEFINITION OF TERMS Section 1. Title. This ordinance shall be known as the Revenue Code of the City of Malaybalay. Section 2. Scope and Application. This Code shall govern the levy, assessment, and collection of taxes, fees, charges and other impositions within the territorial jurisdiction of this City. 1 Article 2 CONSTRUCTION OF PROVISIONS Section 3. Words and Phrases Not Herein Expressly Defined. Words and phrases embodied in this Code not herein specifically defined shall have the same definitions as found in R.A No. -

KATRIBU Special-Report on Ips and COVID-19

Special Report June, 2020 Phil. IPs amidst Covid-19 pandemic: From north to south Indigenous Peoples are battling against discrimination, militarization and worsening human rights situation Executive Summary: I ndigenous Peoples in the Philippines approximately Likewise, government and private business interests have comprise 15 million of the country‟s 108 million popu- seized the opportunities provided by health crisis situa- lation. Indigenous peoples are composed of more than tions to further encroach on the lands and territories of 100 groups and are located in 50 of the country‟s 78 IPs. The joint proposal of the Department of Agriculture provinces. They inhabit more than five million hectares (DA) and National Commission on Indigenous Peoples of ancestral lands of the country‟s total landmass of 30 (NCIP). To undertake the „Plant, Plant, Plant‟ program is million hectares. maliciously using the crisis to land grab remaining ances- tral lands of the Lumad in Mindanao, while operations of Months into the crisis brought about by Covid-19 pan- destructive and exploitative projects continue unabatedly demic, the situation of the Indigenous Peoples, from amidst Covid-19 pandemic. north to south is slowly coming to light with the reports coming from different indigenous organizations and These realities on the ground are consequences of the communities. As the Enhanced Community Quarantine utter of the national government to draw up a prompt and (ECQ) was declared nationwide, the 15 million Indige- comprehensive plan to manage the health crisis and im- nous Peoples (IPs), in the country are facing particularly pact on the socio-economic well-being of the people. -

Postal Code Province City Barangay Amti Bao-Yan Danac East Danac West

Postal Code Province City Barangay Amti Bao-Yan Danac East Danac West 2815 Dao-Angan Boliney Dumagas Kilong-Olao Poblacion (Boliney) Abang Bangbangcag Bangcagan Banglolao Bugbog Calao Dugong Labon Layugan Madalipay North Poblacion 2805 Bucay Pagala Pakiling Palaquio Patoc Quimloong Salnec San Miguel Siblong South Poblacion Tabiog Ducligan Labaan 2817 Bucloc Lamao Lingay Ableg Cabaruyan 2816 Pikek Daguioman Tui Abaquid Cabaruan Caupasan Danglas 2825 Danglas Nagaparan Padangitan Pangal Bayaan Cabaroan Calumbaya Cardona Isit Kimmalaba Libtec Lub-Lubba 2801 Dolores Mudiit Namit-Ingan Pacac Poblacion Salucag Talogtog Taping Benben (Bonbon) Bulbulala Buli Canan (Gapan) Liguis Malabbaga 2826 La Paz Mudeng Pidipid Poblacion San Gregorio Toon Udangan Bacag Buneg Guinguinabang 2821 Lacub Lan-Ag Pacoc Poblacion (Talampac) Aguet Bacooc Balais Cayapa Dalaguisen Laang Lagben Laguiben Nagtipulan 2802 Nagtupacan Lagangilang Paganao Pawa Poblacion Presentar San Isidro Tagodtod Taping Ba-I Collago Pang-Ot 2824 Lagayan Poblacion Pulot Baac Dalayap (Nalaas) Mabungtot 2807 Malapaao Langiden Poblacion Quillat Bonglo (Patagui) Bulbulala Cawayan Domenglay Lenneng Mapisla 2819 Mogao Nalbuan Licuan-Baay (Licuan) Poblacion Subagan Tumalip Ampalioc Barit Gayaman Lul-Luno 2813 Abra Luba Luzong Nagbukel-Tuquipa Poblacion Sabnangan Bayabas Binasaran Buanao Dulao Duldulao Gacab 2820 Lat-Ey Malibcong Malibcong Mataragan Pacgued Taripan Umnap Ayyeng Catacdegan Nuevo Catacdegan Viejo Luzong San Jose Norte San Jose Sur 2810 Manabo San Juan Norte San Juan Sur San Ramon East -

List of On-Process Cadts in Region 10 (Direct CADT Applications) Est

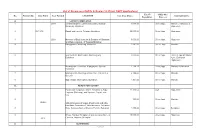

List of On-process CADTs in Region 10 (Direct CADT Applications) Est. IP CADC No./ No. Petition No. Date Filed Year Funded LOCATION Est. Area (Has.) Claimant ICC/s Population Process A.6. 03/25/95 Kibalagon SURVEY Lot COMPLETED2 (CMU) 601.00 Direct App. Manobo-Talaandig 1. 2004 Central Mindanao University (CMU), Musuan, 3,080.00 Direct App. Manobo, Talaandig & Maramag, Bukidnon Higa-onon 2. 05/13/02 Basak and Lantud, Talakag, Bukidnon 20,000.00 Direct App. Higa-onon 3. 2008 Maecate of Brgy, Laculac & Sagaran of Baungon 5,000.00 Direct App. Higaonon and Dagondalahon of Talakag,Bukidnon 4. Danggawan, Maramag, Bukidnon 1,941.92 Direct App. Manobo 5. Guinawahan, Bontongan, Impasug-ong, 3,000.00 Direct App. Heirs of Apo Bartolome Bukidnon Ayoc (Bukidnon- Higaonon) 6. Merangeran, Lumintao, Kipaypayon, Quezon 7,294.73 Direct App. Manobo-Kulamanen Bukidnon 7. Banlag & Sto. Domingo of Quezon , Valencia & 2,154.00 Direct App. Manobo Quezon 8. San nicolas, Don Carlos, Bukidnon 1,401.00 Direct App. Manobo B. READY FOR SURVEY 1. Palabukan (Tagiptip),Libona, Bukidnon & Brgy. 11,193.54 AO1 Higa-onon Cugman (Malasag), and Agusan, Cag de Oro City 2. 120.00 Direct App. Manobo 1/14/02 Sitio Kiramanon of Brgys. Panalsalan and Sitio Kawilihan Dagumbaan, Mun Maramag, Bukidnon 3. Brgy. Santiago Mun of Manolo Fortich, Bukidnon 1,450.00 Direct App. Bukidnon 4. Brgys. Plaridel, Hinaplanon and Gumaod, Mun. of 10,000.00 Direct App. Higaonon 2012 Claveria, Misamis Oriengtal C. SUSPENDED Page 1 of 6 Est. IP CADC No./ No. Petition No. Date Filed Year Funded LOCATION Est. -

Attitudes and Influences Relevant to Golden Rice's Potential Use in the Philippines

Attitudes and Influences relevant to Golden Rice’s potential use in the Philippines Sheila Grace Abalajen, Abul Khayr Alonto II, Karen Bitagun, Joana Capareda, Johan Diaz, Ryan Miranda, Daciano Palami and Ma. Theresita Tiongco‐Quinto Research conducted, and this report, http://www.goldenrice.org/PDFs/GR_FR_Story%20Board.pdf written and accompanying presentation, http://www.goldenrice.org/PDFs/AIM_GR_Rep_2009.pdf prepared in 2009. Notes: Barangay = the smallest unit of government organisation in the Philippines BFAD = Bureau of Food and Drugs. Philippines equivalent of US FDA, but includes food approval. BHW = Barangay Health Worker BNS = Barangay Nutrition Scholar CAO = City Agricultural Office (‘CAO Technicians are front line for Government coordination with farmers, but the CAO technicians find it difficult to delineate themselves from the Department of Agriculture advisors’) DA = Department of Agriculture DOH = Department of Health DSWD = Department of Social Welfare & Development Kuhol = snail LGU = Local Government Unit ‘Melamine’ is a plastic. Around the time of this research fraudsters in China had been found guilty of adulterating ground rice, used for example in baby food, with powdered melamine NFA = (National Food Authority) Philippine government stockpiled rice, provided at subsidised price to assist food security (which, it is reputed, has often been improperly stored) Patak Pinoy = literally ‘Philippine Drops’: Philippine government endorsed vitamin A distribution programme, designed to combat VAD. RHU = Regional Health Unit ‘Salmon’ = (used) tin of salmon used to measure volume of rice. I Salmon = 1Kg uncooked rice ‘Viand’ = any component of a meal which is not rice. (In the Philippines any food consumed without rice, is not considered a meal.) Suggested citation: Abalajen S, Alonto II K, Bitagun K, et al (2020). -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population BUKIDNON

2010 Census of Population and Housing Bukidnon Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population BUKIDNON 1,299,192 BAUNGON 32,868 Balintad 660 Buenavista 1,072 Danatag 2,585 Kalilangan 883 Lacolac 685 Langaon 1,044 Liboran 3,094 Lingating 4,726 Mabuhay 1,628 Mabunga 1,162 Nicdao 1,938 Imbatug (Pob.) 5,231 Pualas 2,065 Salimbalan 2,915 San Vicente 2,143 San Miguel 1,037 DAMULOG 25,538 Aludas 471 Angga-an 1,320 Tangkulan (Jose Rizal) 2,040 Kinapat 550 Kiraon 586 Kitingting 726 Lagandang 1,060 Macapari 1,255 Maican 989 Migcawayan 1,389 New Compostela 1,066 Old Damulog 1,546 Omonay 4,549 Poblacion (New Damulog) 4,349 Pocopoco 880 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Bukidnon Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Sampagar 2,019 San Isidro 743 DANGCAGAN 22,448 Barongcot 2,006 Bugwak 596 Dolorosa 1,015 Kapalaran 1,458 Kianggat 1,527 Lourdes 749 Macarthur 802 Miaray 3,268 Migcuya 1,075 New Visayas 977 Osmeña 1,383 Poblacion 5,782 Sagbayan 1,019 San Vicente 791 DON CARLOS 64,334 Cabadiangan 460 Bocboc 2,668 Buyot 1,038 Calaocalao 2,720 Don Carlos Norte 5,889 Embayao 1,099 Kalubihon 1,207 Kasigkot 1,193 Kawilihan 1,053 Kiara 2,684 Kibatang 2,147 Mahayahay 833 Manlamonay 1,556 Maraymaray 3,593 Mauswagon 1,081 Minsalagan 817 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population and Housing Bukidnon Total Population by Province, -

Bukidnon Region X

CY 2010 INTERNAL REVENUE ALLOTMENT FOR BARANGAYS PrOVINCE OF BUKIDNON REGION X COMPUTATION OF THE CY 2010 INTERNAL REVENUE ALLOTMENT CY 2007 BARANGAY Census of P80,000 Population FOR BRGYS. SHARE EQUAL TOTAL W/ 100 OR MOR BASED ON SHARING (ROUNDED) POPULATION POPULATION 01 BAUNGON 1 Balintad 599 80,000 197,920.32 463,312.44 741,233.00 2 Buenavista 730 80,000 241,205.06 463,312.44 784,518.00 3 Danatag 2,544 80,000 840,583.11 463,312.44 1,383,896.00 4 Imbatug (Pob.) 4,619 80,000 1,526,200.23 463,312.44 2,069,513.00 5 Kalilangan 753 80,000 248,804.67 463,312.44 792,117.00 6 Lacolac 748 80,000 247,152.58 463,312.44 790,465.00 7 Langaon 874 80,000 288,785.24 463,312.44 832,098.00 8 Liboran 2,828 80,000 934,421.79 463,312.44 1,477,734.00 9 Lingating 3,639 80,000 1,202,390.70 463,312.44 1,745,703.00 10 Mabuhay 1,369 80,000 452,342.09 463,312.44 995,655.00 11 Mabunga 1,106 80,000 365,442.19 463,312.44 908,755.00 12 Nicdao 1,932 80,000 638,367.36 463,312.44 1,181,680.00 13 Pualas 1,952 80,000 644,975.72 463,312.44 1,188,288.00 14 Salimbalan 2,733 80,000 903,032.09 463,312.44 1,446,345.00 15 San Miguel 821 80,000 271,273.09 463,312.44 814,586.00 16 San Vicente 2,510 80,000 829,348.90 463,312.44 1,372,661.00 ----------------------- -------------------- ----------------------------- ----------------------------- ------------------------- 29,757 1,280,000 9,832,245.14 7,412,999.09 18,525,247.00 ============= =========== ================ ================ ============== 2 CABANGLASAN 1 Anlogan 1,664 80,000 549,815.37 463,312.44 1,093,128.00 2 Cabulohan -

January 2013

January 2013 MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 1 2 3 4 5 6 MOU Signing with Provincial Child Labor Committee @ DOLE, Malaybalay City 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Confer with Councilor DOLE Bukidnon FFWC-10 General Alexander S. Dacer, PFO Planning & Assembly @ De CDO Committee on Teambuilding @ Luxe Hotel, CDO Labor & Employment, Dahilayan, Manolo RE: SRS Fortick implementation in CDO @ City Hall, CDO 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Advocacy General Assembly MANCOM Career Guidance Program @ Meeting @ Meeting @ @ Miglamin Barangays Jose Quezon, Bukidnon WODP, CDO National High and Poblacion, MANCOM Meeting Career Coaching School, Quezon, @ WODP, CDO @ Salay National Malaybalay City Bukidnon High School, Mis. Career Guidance CLMS Advocacy Or. @ Managok, Program @ Brgy. Career Guidance National High San Jose, @ St. Peter School, Poblacion, Annex, Malaybalay City Quezon Malaybalay City Career Guidance @ Zamboangita High School, Malaybalay City 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 Distribution of Career Guidance Tripartite Medical and WMO-CDO TIPC Kapatiran Self-Assessment @ St. Isidore Certification Dental Mission & RTIPC Joint Orientation Forms @ CDO Academy, Committee @ Quezon, Redirection @ WODP Provincial Sinanglanan, Meeting @ De Bukidnon Meeting @ Training Planning @ Malaybalay City Luxe Hotel, CDO Career WODP, CDO Center, DOLE Eastern Career Guidance Barangay Child Guidance @ Eastern Mis. Or. CDO Mis. Or., @ San Martin Protection Bangcud Career Guidance Villanueva, Mis. National High Committee Re- National High Network & PESO -

Davao Region)

Mindanao Philippines: Region 11 (Davao Region) Binongan Sayon Pulang-Lupa San Ignacio Jasaan Paradise Santa Cruz Sisimon Limot Aurora New Trento Simaya Agusan del Sur Veruela San Visayas Salvacion Surigao San Martn Cabanglasan Jose Union Mandus Malaybalay City Langkila-An del Sur Santo Niño Santa Josefa Sabud Il Papa Mailag Sinanglanan El Katpunan Awao Pagtla- An Tugop Simulao Mansa-Ilao Nabago Apo Macote Datu Davao Lingig San Isidro Malayanan Nacabuklad Andap Angas San Doña Josefa Pasian Roque Vintar Melale Sinabuagan Lumbayao Datu Sisimon Awao Ampunan Malinao Boston Tongantongan Litle Candelaria Aguinaldo Baguio Gupitan Kidawa Cawayanan Santa Emilia Rizal Kawayan San Jose Concepcion Halapitan Kapalong New Haguimitan Laligan Valencia City Monte Dujali Bethlehem Anitap Kiokmay Mabuhay Magkalungay Laak Monkayo Baylo Carmen Poblacion Ampawid Belmonte Banlag Bullucan Cabasagan Concepcion Casoon Banlag Santo Niño Namnam Salvacion Kibongcog Iglugsad Mabuhay Laac Upper Ulip Mount Diwata Dagat-Kidavao Datu Balong Poblacion Abijod San Fernando Mainit Langtud San Isidro Olaycon Panamoren Union Dacudao San Antonio Bukidnon Cateel San Paitan Lumintao Inambatan San Alfonso Bonacao Miguel Sua-On Inacayan Camansa Tubo-tubo San Vicente Kilagding Prosperidad San Palacpacan San Jose Aragon Kipaypayon Imelda Rafael Linao Malibago Dao Longanapan Mamunga Alegria San Miguel Banglasan Aliwagwag Dumalama New Taytayan Santo Domingo Libuton Tapia Naboc Mangayon Binasbas Cebulida Naga Binancian Calape Maglahus Magsaysay Davao del Norte Kaligutan Canidkid Banao -

P8,381000.00 Region 10 Province City/Mun Barangay Farmer Association/Cooperative # Name of Farmers Bukidnon Cabangl

1. 15,293 units Laminated Sack (2.4m X 10m) Allocation: P8,381,000.00 Region 10 Province City/Mun Barangay Farmer Association/Cooperative # Name of Farmers Bukidnon Cabanglasan Anlugan 1 Doroteo Omagap, Sr. Bukidnon Cabanglasan Anlugan 2 Ferdinand Diwan Bukidnon Cabanglasan Anlugan 3 Ricardo Baclawon Bukidnon Cabanglasan Anlugan 4 Sergio Papasin, Jr. Bukidnon Cabanglasan Anlugan 5 Melvin Ferrera Bukidnon Cabanglasan Anlugan 6 Jesus Vicoy Bukidnon Cabanglasan Anlugan 7 Dolorosa Sistoso Bukidnon Cabanglasan Anlugan 8 Rosito Campoid, Jr. Bukidnon Cabanglasan Anlugan 9 Lourdes Balindres Bukidnon Cabanglasan Anlugan 10 Lila Santala Bukidnon Cabanglasan Anlugan 11 Felipa Oljal Bukidnon Cabanglasan Anlugan 12 Ronie Tingcang Bukidnon Cabanglasan Anlugan 13 Josefina Diwan Bukidnon Cabanglasan Anlugan 14 Eusebia Vicoy Bukidnon Cabanglasan Anlugan 15 Wilma Renos Bukidnon Cabanglasan Anlugan 16 Casimer Pantonial Bukidnon Cabanglasan Anlugan 17 Dionesio Beliran Bukidnon Cabanglasan Anlugan 18 Leandro Arambala Bukidnon Cabanglasan Anlugan 19 Jijo Butalid Bukidnon Cabanglasan Anlugan 20 Estrella Bangot Bukidnon Cabanglasan Anlugan 21 Gilbert Duenas Bukidnon Cabanglasan Anlugan 22 Letecia Tingcang Bukidnon Cabanglasan Anlugan 23 Manuelito Ratilla Bukidnon Cabanglasan Anlugan 24 Panfilo Sarajena Bukidnon Cabanglasan Anlugan 25 Rene Sarajena Bukidnon Cabanglasan Cabulohan 26 Caluna, Erec Bukidnon Cabanglasan Cabulohan 27 Cajutol, Nelson Bukidnon Cabanglasan Cabulohan 28 Rosalita, Bernadeth Bukidnon Cabanglasan Cabulohan 29 Lopez, Carmelina Bukidnon Cabanglasan -

NO. Name Residential Address Last Given MI No. Brgy Municipality/Cit Y

REGISTRY OF SPES BENEFICIARIES Regional Office No. X Year: 2018 NO. Name Residential Address Municipality/Cit Last Given MI No. Brgy Province y 1 CABANDA REY SAGISABAL WEST DALURONG KITAO-TAO BUKIDNON 2 BAUTISTA JAYSON LABUCA MAGSAYSAY KITAO-TAO BUKIDNON 3 LUZON PRINCESS YUTO POBLACION KITAO-TAO BUKIDNON 4 BITAYO PEARL DIANNE VALMORES POBLACION KITAO-TAO BUKIDNON 5 GANANCIAL JADE MARK OTERO BERSHIBA KITAO-TAO BUKIDNON 6 BATUTO VEECHEL PERDILAN POBLACION KITAO-TAO BUKIDNON 7 ARTAJO JENEROSE NANGCA STO. ROSARIO KITAO-TAO BUKIDNON 8 RABAGO RIAN MARK PESCADERO STO. ROSARIO KITAO-TAO BUKIDNON 9 CABERTE JERRIED SULANG POBLACION KITAO-TAO BUKIDNON 10 ABELLAR CRISTEL DAWN POBLACION CABANGLASAN BUKIDNON 11 ABANADOR ARIEL PAYAG-AN IBA CABANGLASAN BUKIDNON 12 ACANG ELLEN MAE CALINGASAN POBLACION CABANGLASAN BUKIDNON 13 AQUINO MARRIFEL DULOS MAUSWAGON CABANGLASAN BUKIDNON 14 ARIDIDON HAZEL DAY CAPINONAN CABANGLASAN BUKIDNON 15 ALIGADA JELA VILLARMIA OMALAO FREEDOM CABANGLASAN BUKIDNON 16 AYAWON RONEL PULACAN MANDAHICAN CABANGLASAN BUKIDNON 17 BAÑES MARIA LAURA OSTAN POBLACION CABANGLASAN BUKIDNON 18 BARICUATRO RAMEL LICONDA CANANGA-AN CABANGLASAN BUKIDNON 19 BETARMOS JEAN CLAIRE TAGLINAO CAPINONAN CABANGLASAN BUKIDNON 20 CAMINO GELALYN MACAYA POBLACION CABANGLASAN BUKIDNON 21 CAMPION CRISTIAH MAE CONCEPCION POBLACION CABANGLASAN BUKIDNON 22 CRUZ DELA MARGIE AMPOEDA MANDAHICAN CABANGLASAN BUKIDNON 23 DONDOYANO CARLO ABELLAR POBLACION CABANGLASAN BUKIDNON 24 GALORPORT RYAN PETER ABILLAR POBLACION CABANGLASAN BUKIDNON 25 ITALIA PEARL ANGELIE IBA CABANGLASAN