GRAMOPHONE the World's Authority on Classical Music Since 1923

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In-Depth Analysis and Program Notes on a Selection of Wind Band Music Benjamin James Druffel Minnesota State University - Mankato

Minnesota State University, Mankato Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects 2012 In-Depth Analysis and Program Notes on a Selection of Wind Band Music Benjamin James Druffel Minnesota State University - Mankato Follow this and additional works at: http://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Druffel, Benjamin James, "In-Depth Analysis and Program Notes on a Selection of Wind Band Music" (2012). Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects. Paper 196. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. IN-DEPTH ANALYSIS AND PROGRAM NOTES ON A SELECTION OF WIND BAND MUSIC By Benjamin J. Druffel A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music in Wind Band Conducting Minnesota State University, Mankato Mankato, Minnesota June 2012 In-Depth Analysis and Program Notes on a Selection of Wind Band Music Benjamin J. Druffel This thesis has been examined and approved by the following members of the thesis committee. Dr. Amy K. Roisum-Foley, Advisor Dr. John Lindberg Dr. Linda Duckett ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Dr. Amy Roisum-Foley: Thank you for your knowledge, musicianship, patience, and above all, your friendship. I am honored to have you as a mentor! Dr. -

Photo Needed How Little You

HOW LITTLE YOU ARE For Voices And Guitars BY NICO MUHLY WORLD PREMIERE PHOTO NEEDED Featuring ALLEGRO ENSEMBLE, CONSPIRARE YOUTH CHOIRS Nina Revering, conductor AUSTIN CLASSICAL GUITAR YOUTH ORCHESTRA Brent Baldwin, conductor HOW LITTLE YOU ARE BY NICO MUHLY | WORLD PREMIERE TEXAS PERFORMING ARTS PROGRAM: PLEASESEEINSERTFORTHEFIRSTHALFOFTHISEVENING'SPROGRAM ABOUT THE PROGRAM Sing Gary Barlow & Andrew Lloyd Webber, arr. Ed Lojeski From the first meetings aboutHow Little Renowned choral composer Eric Whitacre You Are, the partnering organizations was asked by Disney executives in 2009 Powerman Graham Reynolds knew we wanted to involve Conspirare to compose for a proposed animated film Youth Choirs and Austin Classical Guitar based on Rudyard Kipling’s beautiful story Libertango Ástor Piazzolla, arr. Oscar Escalada Youth Orchestra in the production and are The Seal Lullaby. Whitacre submitted this Austin Haller, piano delighted that they are performing these beautiful, lyrical work to the studios, but was works. later told that they decided to make “Kung The Seal Lullaby Eric Whitacre Fu Panda” instead. With its universal message issuing a quiet Shenandoah Traditional, arr. Matthew Lyons invitation, Gary Barlow and Andrew Lloyd In honor of the 19th-century American Webber’s Sing, commissioned for Queen poetry inspiring Nico Muhly’s How Little That Lonesome Road James Taylor & Don Grolnick, arr. Matthew Lyons Elizabeth’s Diamond Jubilee in 2012, brings You Are, we chose to end the first half with the sweetness of children’s voices to brilliant two quintessentially American folk songs Featuring relief. arranged for this occasion by Austin native ALLEGRO ENSEMBLE, CONSPIRARE YOUTH CHOIRS Matthew Lyons. The haunting and beautiful Nina Revering, conductor Powerman by iconic Austin composer Shenandoah precedes James Taylor’s That Graham Reynolds was commissioned Lonesome Road, setting the stage for our AUSTIN CLASSICAL GUITAR YOUTH ORCHESTRA by ACG for the YouthFest component of experience of Muhly’s newest masterwork. -

Memories of Aldeburgh

February 2013 Issue 42 Hemiola St George’s Singers INSIDE THIS ISSUE: MEMORIES OF ALDEBURGH Britten at 100—preview 2-3 2013 is a special year for fans of atmosphere created by Diary of a recording 4-5 Benjamin Britten, as the nation performing St Nicolas in Christmas concert review 6 celebrates the 100th birthday of the church where it was Singing Day success 7 one of our greatest composers. first performed and record- SGS News 8 For St George’s Singers, our ed, where Britten’s funeral Jeff takes to the streets 9 ‘Britten at 100’ concert on 23 had included the two February at RNCM also brings hymns from the work, and Name that tune 10 The staging party 11 back happy memories of the beside the Piper memorial Pilgrimage to Leipzig 12-13 Choir’s tour to Suffolk in 2005, window, intensified the when we performed St Nicolas emotion of the occasion. Fit to sing 14 in Britten’s own church in In the first half Marcus Eric Whitacre on choirs 15 Aldeburgh. Geoff Taylor or- [Farnsworth] sang Let the St George’s in China 16-17 ganised the tour, and wrote the Dreadful Engines and Even- following for Hemiola: ing Hymn by Purcell, and The bear goes home 18 The trees they grow so high, Mindful music 19 ‘On Saturday morning we trav- arranged by Britten. Jeff elled through the Suffolk by- played a Bach prelude and ways to Snape Maltings where ST GEORGE’S SINGERS Britten’s Prelude and Fugue Esther Platten, who works for PRESIDENT: on a Theme of Vittoria brilliant- John Piper’s memorial window to Benjamin the Britten-Pears Foundation, ly. -

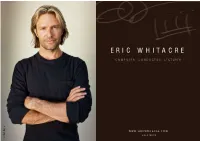

Eric Whitacre Press

E R I C W H I T A C R E E R I C W H I T A C R E C O M P O S E R , C O N D U C T O R , L E C T U R E R e c y o R W W W . E R I C W H I T A C R E . C O M c r a M J U L Y 2 0 1 2 © Music Productions Ltd. - +44 (0) 1753 783 739 - Claire Long, Manager - [email protected] E R I C W H I T A C R E B I O G R A P H Y ´:KLWDFUHLVWKDWUDUHWKLQJDPRGHUQFRPSRVHUZKRLV Eric Whitacre is one of the most popular and performed His latest initiative, Soaring Leap, is a series of workshops and ERWK SRSXODU DQG RULJLQDOµ 7KH 'DLO\ 7HOHJUDSK composers of our time, a distinguished conductor, broadcaster festivals. Guest speakers, composers and artists, make regular and public speaker. His first album as both composer and appearances at Soaring Leap events around the world. conductor on Decca/Universal, Light & Gold, won a Grammy® in 2012, reaped unanimous five star reviews and became the An exceptional orator, he was honoured to address the U.N. no. 1 classical album in the US and UK charts within a week of Leaders programme and give a TEDTalk in March 2011 in which release. His second album, Water Night, was released on Decca he earned the first full standing ovation of the conference. He in April 2012 and debuted at no. -

Join the World's Largest Virtual Choir | Eric Whitacre, Deep Field

ERIC WHITACRE’S VIRTUAL CHOIR 5: DEEP FIELD - PRESS RELEASE – TUESDAY JUNE 5, 2018 “Humanity’s most basic instincts are often expressed in discovery and music. Hubble Telescope’s images of the Deep Field, which fundamentally changed the way we understand the Universe, have been transformed into inspired music by composer Eric Whitacre. Combining the voices of thousands of singers from around the world in the Virtual Choir with symphony orchestra and Hubble’s extraordinary images of the cosmos, will a truly mind-blowing experience.” Dr. Robert Williams | Astrophysicist, Former Director - Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) Join the World’s largest Virtual Choir | Eric Whitacre, Deep Field Submissions are now open for Eric Whitacre’s Virtual Choir 5: Deep Field (VC5). Singers are invited to record and upload their video to become part of a new digital art film created by Eric Whitacre and Music Productions in collaboration with the Space Telescope Science Institute and 59 Productions. Grammy-winning composer and conductor Eric Whitacre’s Deep Field, scored for orchestra, choir and electronics, is inspired by the revolutionary discoveries of the determined scientific visionaries working with the Hubble Space Telescope. VC5 opens on Tuesday June 5 and closes on Wednesday June 27 at 11:59pm PST. The Music: Twenty-eight years ago, NASA’s Space Shuttle Discovery launched the Hubble Space Telescope into orbit. The vast map of our universe that it produced stands as one of the most important scientific discoveries of the twentieth century. It is a story of human endeavor, wonder and extraordinary scientific ambition. This story was the inspiration behind Eric Whitacre’s Deep Field which was commissioned by the Minnesota Orchestra and BBC Radio 3 for the BBC Proms. -

Jeff Beal the Salvage Men

JEFF BEAL THE SALVAGE MEN Eric Whitacre, conductor Eric Whitacre Singers Live at Union Chapel, London TRACK LIstING THE SALVAGE MEN 1. A VERY LONG MOMENT 06:01 2. SPIDERWEB 05:05 3. VIRGA 05:48 4. AGE 04:00 5. SALVAGE 06:44 JEFF BEAL Jeff Beal is an American composer of music for film, media, and the concert hall. With musical beginnings as a jazz trumpeter and recording artist, his works are infused with an understanding of rhythm and spontaneity. Steven Schneider for the New York Times wrote of “the richness of Beal’s musical thinking...his compositions often capture the liveliness and unpredictability of the best improvisation.” Beal’s seven solo CDs, including Three Graces, Contemplations (Triloka) Red Shift (Koch Jazz), and Liberation (Island Records) established him as a respected recording artist and composer. Beal’s eclectic music has been singled out with critical acclaim and recognition. His score and theme for Netflix drama,House of Cards, have earned him several Emmy Awards, most recently in 2015. Other scores of note include his dramatic music for HBO’s acclaimed series Carnivale and Rome, as well as his comedic score and theme for the detective series, Monk. Beal composes, orchestrates, conducts, records and mixes his own scores, which gives his music a very personal, distinctive touch. Beal’s commissioned works have been performed by many leading orchestras and conductors, including the St. Louis (Marin Alsop), Rochester, Pacific (Carl St. Clair), Frankfurt, Munich, and Detroit (Neeme Jaarvi) symphony orchestras. The Salvage Men is his first choral piece written for the Eric Whitacre Singers and the Los Angeles Master Chorale. -

CONDUCTOR/ COMPOSER ERIC WHITACRE UNVEILS BEHIND-THE-SCENES DOCUMENTARY ABOUT MAKING MUSIC DURING PANDEMIC Free Video Streaming Now Available

CONDUCTOR/ COMPOSER ERIC WHITACRE UNVEILS BEHIND-THE-SCENES DOCUMENTARY ABOUT MAKING MUSIC DURING PANDEMIC Free video streaming now available. PALO ALTO, CA (25 August 2021) — Grammy Award-winning conductor and composer Eric Whitacre, whose worldwide audiences number in the millions, has released a behind-the-scenes documentary showing how young singers struggling with the loss of making live music were able to unite during the pandemic to perform together virtually. Titled Sing Gently: Behind the Scenes with JackTrip and Eric Whitacre, this compelling video shares how profoundly affected young singers were when COVID 19 protocols prohibited singing in groups, and how deeply moved Whitacre was when finally able to conduct his first ever live online choral performance using a new groundbreaking tech created by Silicon Valley startup JackTrip Labs. Featuring dozens of young chorus members singing live from locations hundreds of miles apart, the concert was livestreamed in May 2021 and watched by thousands. The performance marked the World Premiere of the SSA (youth voices) arrangement of “Sing Gently”—a touching paean to the power of music viewed by millions around the world— performed live by young choristers from Ragazzi Boys Chorus, San Francisco Girls Chorus, and Southern California Children’s Chorus singing together in real time as conducted by Whitacre. In this short film, Whitacre and the young singers describe their feelings of isolation, frustration trying to sing with cohorts using existing video conferencing tools, and the excitement of finally performing together in real-time after more than a year apart. Sing Gently: Behind the Scenes with JackTrip and Eric Whitacre is available to stream FREE on Whitacre’s YouTube page (youtube.com/c/EricWhitacre), premiering 9am PDT/ 12pm EDT/ 5pm BST. -

THE IMPOSSIBLE MAGNITUDE of OUR UNIVERSE RESOURCES & EDUCATIONAL MATERIAL Deepfieldfilm.Com

DEEP FIELD: THE IMPOSSIBLE MAGNITUDE OF OUR UNIVERSE RESOURCES & EDUCATIONAL MATERIAL deepfieldfilm.com Grammy® award-winning American composer Eric Whitacre’s symphonic work Deep Field was inspired by the world’s most famous space observatory, the Hubble Space Telescope, and its greatest discovery – the iconic Deep Field image. The new film – Deep Field: The Impossible Magnitude of our Universe – illuminates the score by combining Hubble’s stunning imagery, including never-seen-before galaxy fly-bys, with bespoke animations to create an immersive, unforgettable journey from planet Earth to the furthest edges of our universe. The film is a first-of-its-kind collaboration between composer & conductor Eric Whitacre, producers Music Productions, scientists and visualizers from the Space Telescope Science Institute and Tony award-winning artists 59 Productions. The score and film paint the incredible story of the Hubble Deep Field. Turning its gaze to a tiny and seemingly dark area of space (around one 24-millionth of the sky) for an 11-day long period, the Hubble Space Telescope revealed over 3,000 galaxies that had never previously been seen, each one composed of hundreds of billions of stars. This discovery fundamentally changed the way we understand the universe. The soundtrack features a new, epic Virtual Choir representing 120 countries: over 8,000 voices aged 4 to 87, alongside the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and Eric Whitacre Singers. In April 2020, the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope will celebrate 30 years since its launch. https://www.spacetelescope.org/projects/Hubble30/ https://hubblesite.org/30 Deep Field: The Impossible Magnitude of our Universe is available upon request for: - Film screenings (DCP available) - Educational screenings - To accompany live performances with orchestra & choir - Museums, galleries, science or music festivals, concerts This document is intended to give an overview of the existing free resources that can be used in the classroom or to promote events. -

Eric Whitacre's Virtual Choir 6: “Sing Gently”

Over 17,500 singers aged 5 to 88 from 129 Countries join Eric Whitacre’s Virtual Choir 6: “Sing Gently” Premiere – Sunday, July 19, 2020 [Los Angeles, CA – June 18th, 2020] Moved by the breadth of the pandemic and effect on society, one of the world’s most performed composers, Eric Whitacre, composed a new piece especially for his Virtual Choir - “Sing Gently.” 17,572 singers from 129 countries, aged 5–88, recorded their videos to be combined to form Virtual Choir 6. Together they found strength in the simple, collective initiative of the project and saw it as a way to not only replenish from within but also to offer hope and relief for the sadness and suffering of others. Virtual Choir 6, the film, will premiere on YouTube Sunday, July 19 at 10:30am PDT. “With everyone unexpectedly far apart from each other I found myself thinking about the virtues of empathy, community and service, and a new Virtual Choir felt like a deeply human way to address all of those virtues. I tried as best I could to keep the lyrics of ‘Sing Gently’ straightforward and unadorned, to simply say what I felt needed to be said.” Eric Whitacre This marks Whitacre’s largest Virtual Choir to date since his first more than 10 years ago. It is a testament to diversity, accessibility and inclusivity, and much more than a musical project; it’s a community. To make Virtual Choir 6, Whitacre and his managers & producers at Music Productions teamed-up with two organizations that share their commitment to expand access to the performing arts: the Colburn School and The NAMM Foundation. -

We Sing Journeys

we sing journeys JOBY TALBOT’s PATH OF MIRACLES AND MUSIC OF ERIC WHITACRE & PETER SCOTT LEWIS JANUARY 19-22 1 PATH OF MIRACLES Thursday, January 19, 2012, 7:30 pm St. Mary’s Catholic Church, Fredericksburg Friday, January 20, 8:00 pm Saturday, January 21, 8:00 pm Sunday, January 22, 3:00 pm St. Martin’s Lutheran Church, Austin Presented with support from The Keating Family Foundation Additional support provided by SpanishSteps.com Co-sponsored by Seton Cove & Humanities Texas MUSIC OF ERIC WHITACRE & PETER SCOTT LEWIS Saturday, January 21, 5:00 pm St. Martin’s Lutheran Church, Austin Craig Hella Johnson, Artistic Director & Conductor Company of Voices Season Sustaining Underwriter 2011-2012 SEASON SUSTAINING UNDERWRITER OF CONSPIRARE 2 3 Special Thanks Program Path of Miracles by Joby Talbot (b. 1971) We thank the Fredericksburg Friends of Conspirare whose generous gifts support the January 19 performance: 1. Roncesvalles Donors Fischer & Wieser Specialty Foods 2. Burgos Timothy Koock Susan & Frosty Rees 3. Leon Dian & Harlan Stai 4. Santiago Special Appreciation Saint Mary’s Catholic Church – Mgsr. Enda McKenna, pastor Fredericksburg Music Club – Mark Eckhardt & Judy Hickerson Path of Miracles will be performed without intermission. Table of Contents PATH OF MIRACLES Program Notes Program ......................................................................................... 5 Spain’s Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela is one of the revered “thin Notes .......................................................................................... 5-7 places” of the world, a shrine where the border between earth and heaven Texts & Translations ....................................................................8-14 is felt to disappear. Since the ninth century, pilgrims have followed an ancient route leading from France to the cathedral shrine holding the body of St. -

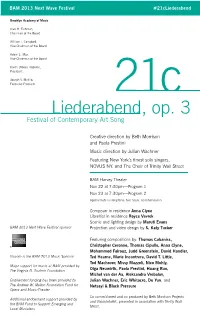

21C Liederabend , Op 3

BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival #21cLiederabend Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer 21c Liederabend, op. 3 Festival of Contemporary Art Song Creative direction by Beth Morrison and Paola Prestini Music direction by Julian Wachner Featuring New York’s finest solo singers, NOVUS NY, and The Choir of Trinity Wall Street BAM Harvey Theater Nov 22 at 7:30pm—Program 1 Nov 23 at 7:30pm—Program 2 Approximate running time: two hours, no intermission Composer in residence Anna Clyne Librettist in residence Royce Vavrek Scenic and lighting design by Maruti Evans BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival sponsor Projection and video design by S. Katy Tucker Featuring compositions by: Thomas Cabaniss, Christopher Ceronne, Thomas Cipullo, Anna Clyne, Mohammed Fairouz, Judd Greenstein, David Handler, Viacom is the BAM 2013 Music Sponsor Ted Hearne, Marie Incontrera, David T. Little, Tod Machover, Missy Mazzoli, Nico Muhly, Major support for music at BAM provided by The Virginia B. Toulmin Foundation Olga Neuwirth, Paola Prestini, Huang Ruo, Michel van der Aa, Aleksandra Vrebalov, Endowment funding has been provided by Julian Wachner, Eric Whitacre, Du Yun, and The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Fund for Netsayi & Black Pressure Opera and Music-Theater Co-commisioned and co-produced by Beth Morrison Projects Additional endowment support provided by and VisionIntoArt, presented in association with Trinity Wall the BAM Fund to Support Emerging and Street. Local Musicians 21c Liederabend Op. 3 Being educated in a classical conservatory, the Liederabend (literally “Song Night” and pronounced “leader-ah-bent”) was a major part of our vocal educations. -

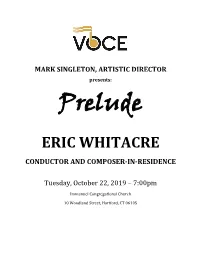

Eric Whitacre Conductor and Composer-In-Residence

MARK SINGLETON, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR presents: Prelude ERIC WHITACRE CONDUCTOR AND COMPOSER-IN-RESIDENCE Tuesday, October 22, 2019 – 7:00pm Immanuel Congregational Church 10 Woodland Street, Hartford, CT 06105 We Don’t Follow The Latest Trends. WE’RE OUT AHEAD OF THEM. At Seabury, the future is already here. Our recent expansion is complete, with state-of-the-art features and amenities, including: Environmental Sustainability Solar, car charging, geothermal, protected land and open space Residence Style Choices Beautifully-appointed apartments and cottages Innovative Fitness & Wellness Personal training, land and water-based group exercise classes, recreational sports Flexible Dining Options Casual bistro, upscale dining room and marketplace options Diverse Lifestyle Possibilities Visual and performing arts, lifelong earning, volunteerism And More! Call 860-243-4033 or 860-243-6018 to schedule a tour today, or sign up for our twice-monthly information sessions. 200 Seabury Drive Bloomfield, CT 06002 www.seaburylife.org PROGRAM All works composed by Eric Whitacre (b.1970) Act 1: Lux Nova The City and the Sea I. i walked the boulevard II. the moon is hiding in her hair III. maggie and milly and molly and may IV. as is the sea marvelous V. little man in a hurry A Boy and a Girl Leonardo Dreams of His Flying Machine The Seal Lullaby ~ Intermission ~ Act 2: Cloudburst Featuring Primi Voci of the Connecticut Children’s Chorus Selections from The Sacred Veil III. Home VII. I am Here VIII. Delicious Times XI. You Rise, I Fall XII. Child of Wonder ~ Fini ~ Encore Sleep Texts and Translations Lux Nova Text by Edward Esch (b.