Newsletter 70: August 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pov Spring 2017

Pints Of View Spring 2017 The Crossways wins Top Pub again. Free: please read here or take away CAMPAIGN FOR REAL ALE 230 Hatfield Road,St Albans, Herts, AL1 4LW Telephone: 01727 867201. www.camra.org.uk Forthcoming Events Branch Meetings: 13th March: White Horse, Bradford-on-Tone TA4 1HF 10th April: New Inn, Wedmore, BS28 4DU 8th May: Muddled Man, West Chinnock, TA18 7PT 12th June: AGM: Wyvern Club, Taunton, TA1 3BJ WEBSITE:- www.somerset.camra.org.uk Branch Chairman Mick Cleveland: [email protected] Branch Contact & Secretary: Katie Redgate 01823 279962. [email protected] Vice Chairman: Kevin Woodley 01823 431872 Social Secretary & Whats Brewing Contact: position vacant Branch Treasurer: Lyn Heapy [email protected] Membership Secretary: Stephen Walker 01823 413988 Discounts, Loc-Ale and Real Cider Promotion & Apple/Perry Officer: Steve Hawkins [email protected] Public Transport: Phil Emond [email protected] Pub Protection Officer: Barrie Childs 01823 323642 Pubs Officer & What Pub: Andy Jones [email protected] Branch Website; colin.heapy@ yahoo.com Newsletter: Paul Davey [email protected]. 01935 329975 Pints of View Somerset Pints of View is published by the Somerset Branch of the Campaign For Real Ale Ltd. (CAMRA) The views expressed therein are not, necessarily, those of either the Campaign or the Editor. Contributions/Letters are always welcome. Advertising Advertising Rates: Full Page £90; Half Page £55; Quarter Page £25. Repeat advertisements are reduced by 10%. For more information contact Paul Davey by e mail or telephone as above. Copy should be JPG or PDF. Advertisement updates are the responsibility of the advertiser 2 Pints Of View Somerset Pints of view is published in February, May, August and November. -

Ancient Dumnonia

ancient Dumnonia. BT THE REV. W. GRESWELL. he question of the geographical limits of Ancient T Dumnonia lies at the bottom of many problems of Somerset archaeology, not the least being the question of the western boundaries of the County itself. Dcmnonia, Dumnonia and Dz^mnonia are variations of the original name, about which we learn much from Professor Rhys.^ Camden, in his Britannia (vol. i), adopts the form Danmonia apparently to suit a derivation of his own from “ Duns,” a hill, “ moina ” or “mwyn,” a mine, w’hich is surely fanciful, and, therefore, to be rejected. This much seems certain that Dumnonia is the original form of Duffneint, the modern Devonia. This is, of course, an extremely respectable pedigree for the Western County, which seems to be unique in perpetuating in its name, and, to a certain extent, in its history, an ancient Celtic king- dom. Such old kingdoms as “ Demetia,” in South Wales, and “Venedocia” (albeit recognisable in Gwynneth), high up the Severn Valley, about which we read in our earliest records, have gone, but “Dumnonia” lives on in beautiful Devon. It also lives on in West Somerset in history, if not in name, if we mistake not. Historically speaking, we may ask where was Dumnonia ? and who were the Dumnonii ? Professor Rhys reminds us (1). Celtic Britain, by G. Rhys, pp. 290-291. — 176 Papers, §*c. that there were two peoples so called, the one in the South West of the Island and the other in the North, ^ resembling one another in one very important particular, vizo, in living in districts adjoining the seas, and, therefore, in being maritime. -

Devon, Cornwall & Southwest England

© Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 4 DAVID TOMLINSON DAVID INTRODUCING DEVON, CORNWALL & SOUTHWEST ENGLAND WHEN THE REST OF THE NATION WANTS TO ESCAPE, IT’S THIS FAR-FLUNG CORNER OF ENGLAND, THE WESTCOUNTRY, THEY INVARIABLY HEAD FOR. Every year millions of visitors fl ock to the region’s shores to feel the sand between their toes and paddle in the briny blue, and with over 650 miles of coastline and cliff tops to explore, not to mention some of England’s greenest, grandest countryside, it’s not really surprising. But while the stirring scenery is undoubtedly one of the main attractions, there’s much more to this region than just shimmering sands and grandstand views. After decades of economic underinvestment and industrial decline, things are really changing out west. Run-down harbours JURASSIC COAST are being renovated. Celebrity chefs are setting NEIL SETCHFIELD up shop along the coastline. Old fi shing harbours, derelict mining towns and faded seaside resorts are reinventing themselves as cultural centres, artistic havens and gastronomic hubs. Whichever way you look at it, there seems to be something special in the air, and it’s not just the salty tang of sea breeze. Everyone seems to want their own lit- tle slice of the southwest lifestyle these days, and it’s high time you found out why. TOP Bathers bask in the sun by the limestone rock arch, Durdle Door (p102) BOTTOM LEFT The space-age biomes of the Eden Project (p241) BOTTOM RIGHT Bristol’s famous landmark, the Clifton Suspension Bridge (p41) EDEN PROJECT HANTASTICO (HANNAH KING) -

News and Brews News and Brews

NEWS AND BREWS Summer Free Magazine of 2012 The South Devon Branch of FREE THE CAMPAIGN FOR REAL ALE The Rugglestone Inn. South Devon CAMRA s Pub of the Year 20 2 South Devon CAMRA Supporting Real Ale in the South West Welcome to NEWS AND BREWS 3 th EDITION Summer 2012 The National CAMRA Member’s Weekend and AGM was a great success, and enjoyed by all who attended. I make no apology that this issue contains reports of some of the trips and visits made by delegates over the course of the few days. All of the local pubs noticed the difference the event made more customers, more ale drunk and therefore better business. A success story all round. May being Mild Month had some of us becoming excited about the lovely mellow flavours available in local hostelries. There certainly were some good milds out there. Please remember to sign the SAVE YOUR PINT e-petition to protest about the escalating beer duty. A link can be found at http://www.camra.org.uk/ Cheers Tina emmings National AGM Brewery Visits. Unfortunately, owing to computer failure, I was not able to thank our local brewers and cider makers for providing some of the best hospitality available during the National AGM weekend. I now have a chance to do so here. Teignworthy entertained the National E ecutive on Friday afternoon and CAMRA members on two evenings. Dartmoor Brewery and unt s cider also provided two evening sessions. Bays, unters and Red Rock accommodated visitors for an evening. A lot of preparation and effort went into all of these visits and we know it was much appreciated by many CAMRA members from around the country who were fulsome in their praise. -

Quantock Hills Aonb Survey '

T H E Q U A N T 0 C K H I L L S A R E A 0 F 0 U T S T A N D I N G N A T U R A L B E A U T Y An Archaeological Survey SUMMARY REPORT Prepared for Somerset County Planning Department By R. R. J. McDonnell Consultant Field Archaeologist June 1989 CONTENTS page 1.0.0 INTRODUCTION 1 1.0 Objectives 1 2.0 Acknowledgements 1 2.0.0 SUMMARY OF PROPOSALS 2 3.0.0 AREA OF SURVEY 2 1.0 Administrative and AONB designation 2 2.0 Topography 2 3.0 Geology 3 4.0 Soils 3 5.0 Land use 3 6.0 Land O\vnership 4 7.0 Commons 4 8.0 Sites of Special Scientific Interest 5 4.0.0 PRE-SURVEY REPORT 5 1.0 Previous surveys 5 2.0 Sites and Monuments Data 5 3.0 Scheduled Ancient Monuments 6 5.0.0 THE AERIAL PHOTOGRAPHIC EVIDENCE 7 1.0 Methodology 7 2.0 Results 8 3.0 Summary of site types 9 6.0.0 FIELD ASSESSMENT 15 1.0 Objectives 15 2.0 Assessment of the aerial photographic evidence 16 3.0 New sites 17 4.0 Condition of sites 18 7.0.0 RESULTS 20 1.0 Sites by type 20 2.0 Sites by period 21 3.0 Sites and Monuments Register update 21 8.0.0 DISCUSSION 22 1.0 Archaeological by period 22 2.0 Resource management 26 3.0 Scheduled Ancient Monuments 26 4.0 Kilve Pill 27 9.0.0 RECOMMENDATIONS 29 1.0 General recommendations 29 2.0 Specific recommendations 30 10.0.0 CONCLUSION 33 11.0. -

Visit Somerset

Somerset Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty Beautiful coastline Great Adventure National Park Superb Food and Drink Two Historic Cities World Heritage Site Wetlands and Wildlife Be in Somerset welcomed The River Parrett at Langport A land full of character, Our promise? You will leave most accessible, with our villages past our tapestry of beauty, nature and here refreshed, taking border only a two hour small fields and hedgerows whilst admiring fun that boasts world- memories with you to last ride from much of the our wealth of wildlife. Extra moments of all class food and drink forever. You will meet south east or midlands. your senses savouring Somerset. along with the best friendly people, enjoy unique You can be here quicker, in hospitality. This is activities, experience superb for longer, more time to This is your time for adventure. Somerset and whatever scenery and taste our famous experience our World you want from a holiday, agricultural produce. You Heritage site, internationally you will find it here, from will want to return to this important wetlands, long sandy beaches, undiscovered land. Jurassic coast, three areas atmospheric harbours, of Outstanding Natural historic cities, renowned Somerset gives you the Beauty and National Park. countryside and even whole flavour of the south More precious minutes subterranean caves. west whilst being the meandering through quaint Follow Visit Somerset, then large social media icons underneath, plus a desktop/mobile screen for website and www.visitsomerset.co.uk Cider drinking at Wassail Wells Cathedral www.visitsomerset.co.uk Year round Dog Beaches Berrow North and South Bossington Brean Burnham (north of Maddock’s Slade) Blue Anchor Bay Greenaleigh (west of Minehead) Kilve Porlock Weir Sand Bay (Weston-super-Mare) Ladye Bay (Clevedon) Somerset’s coast Middle Hope Burnham-on-Sea inspiring St Audries Bay Uphill (Weston-super-Mare) Somerset’s coast is full rock pavements to sand and then it has more in of surprises. -

Taunton Deane Local Plan Forms the Detailed Part of the Development Plan for Taunton Deane

C O N T E N T S Chapter Page 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 2. Strategy..................................................................................................................... 5 Aims and Objectives ................................................................................................. 5 Strategy..................................................................................................................... 6 S1 General Requirements ................................................................................ 12 S2 Design ......................................................................................................... 15 S3 Mixed-use developments ............................................................................ 16 S4 Rural Centres .............................................................................................. 18 S5 Villages........................................................................................................ 18 S6 Cotford St Luke New Village ....................................................................... 19 S7 Outside Settlements .................................................................................... 19 S8 Best and Most Versatile Agricultural Land................................................... 20 S9 Taunton Town Centre.................................................................................. 21 3. Housing .................................................................................................................. -

Newsletter 82, July 2014

Editorial Many voices in this one - a fair sample of the Society? Many contributors - many thanks. O f Powyses themselves, Llewelyn and Louis, the ‘honeysuckle rogues’ of yore (LIP in 1936 now in Switzerland) as always look on the bright side of life, but take up arms for King Edward and Mrs Simpson in the Abdication crisis. TFP in another of his early pieces looks on the shadow side of village life, but not unpleasantly. The JCP scene is dominated by the launch in Paris of the two-way letters, in the 1950s, between JCP and Henry Miller, edited by Jacqueline Peltier (previously known only in French). A good time was had by all and the first edition has sold out. Also from the 1950s, and a link with Henry Miller, is one of the prefaces JCP wrote for poets whom he knew through letters, this one for Eric Barker, ‘the best-loved poet of Big Sur’. Barker included a poem to JCP in a later collection (can the person who kindly sent this to Editor please make themselves known?) and this is nicely paired by one from Raymond Garlick, JCP’s neighbour in Blaenau Ffestiniog. Susan Rands evokes a privileged childhood in her obituary for her sister Sally Conelly. Sonia Lewis describes the April meeting at Northwold, scene of the opening of Glastonbury. Charles Lock reviews Jeremy Hooker’s latest philosophical-poetical diary, and Hooker reviews two other poets. Remoter Powys connections are with the Quantocks, proof-reading, the CIA, and postcards from Palestine. Our next Newsletter no 83 (November), welcomes a Guest Editor, Chris Thomas. -

Somerset County Herald ‘Local Notes and Queries’ by Paul Mansfield

Somerset County Herald ‘Local Notes and Queries’ by Paul Mansfield July 5th 1919 A challenge to our readers. We have much pleasure in recommencing in this issue our column of Local Notes and Queries which proved such a popular feature of this paper for 20 years, but which we were compelled to discontinue for a time owing to difficulties created by the war. We are particularly anxious that this column should consist as far as possible of notes, queries and replies contributed by our readers themselves, and it will very largely depend upon the assistance we receive from them in this direction whether or not the feature shall be continued. It would of course, be an easy matter for us to get a column of such notes written up each week in our own offices, but this is not our purpose in reintroducing this feature in our paper. We want the column to be almost entirely our readers own column, and if they show by their contributions to it that they appreciate such a feature it will be a pleasure to us to help them in every way we can in making the column interesting and useful. If, on the other hand, the contributions we receive from our readers are so few and far between as to suggest that they take little or no interest in such a column, we shall very soon discontinue it, and insert some other feature in it’s place. We therefore invite any and all of our readers who are in any way interested in such matters to send us short interesting notes or queries on any of the following or kindred subjects relating to the district over which the paper -

Ramblers Routes

Ramblers Routes Ramblers Routes Britain’s best walks from the experts Britain’s best walks from the experts Southern England Southern England 12/11/2014 14:38 09 Porlock to Lynmouth, Exmoor 10 Sampford Brett, Somerset l Distance 26½km/16½ miles l Time 8hrs l Type Wood, moor and coast l Distance 17km/11 miles l Time 5½hrs l Type Hill NAVIGATION LEVEL FITNESS LEVEL NAVIGATION LEVEL FITNESS LEVEL walk magazine winter 2014 winter magazine walk walk magazine winter 2014 winter magazine walk Plan your walk Plan your walk l Bristol PORLOCK l EXMOOR SOMERSET Barnstaple SAMPFORD BRETT P Yeovil P l TRO TRO L Exeter L AR AR l B B A A N Exmouth N O O l Torquay l HY: FI HY: HY: FI HY: P P WHERE: Linear walk from WHERE: Linear walk from Porlock to Lynmouth along Sampford Brett via Bicknoller PHOTOGRA the Coleridge Way extension. along the Quantock ridge to PHOTOGRA START: Porlock Visitor Centre the A358 at Seven Ash. Originally opened in 2005, the Valley of the Rocks, one of the In 1956, the Quantock Hills were village of Sampford Brett, nestling (SS884468), main car park START: Car park opposite Coleridge Way was extended this classic Exmoor sights. made England’s first Area of between Exmoor and the Quantocks, nearby along High Bank. village hall, south of church year to make an overall distance Outstanding Natural Beauty. The and follows a stretch of the Way END: Lynmouth Pavilion in Sampford Brett (ST090401). of some 51 miles – an ideal length 1. START From the visitor centre hills stretch south-east from the before climbing on up to the top National Park Centre along END: Bus stop at Seven Ash for a delightful week’s walking (SS884468), bear L to the junction Bristol Channel to just north of of the hills for an exhilarating The Esplanade (SS722496). -

Eboot – January 2020

eBoot – January 2020 This month’s edition includes: • Message from the Chair • Long weekend on Dartmoor, June 2020 • Weekend walking on the Isle of Wight, June 2020 • Weekend walking around Brecon, September 2020 • Bristol’s Public Rights of Way • Notices • Forthcoming walks • Discounts for Ramblers members Join us on Facebook: www.facebook.com/groups/bristolramblersgroup/ From Wendy Britton, Chair of Bristol Ramblers Group Season’s Greetings everyone. Another year ahead and as you will see be- low, an interesting selection of walks from the main programme to entice you out in January. Many thanks to all walk leaders for continuing to sup- ply us with such a variety of walks. You will note there are at least two ‘themed’ walks on offer this month - bridges and churches, we are spoiled for choice, both in Bristol on the same day! And later in the month our battle with the Swan - see the Star walk on the 26th. The committee has received feedback that there could be an appetite for walks that have a focus on flora, fauna, geology, landscape etc. Are there any among you who have the relevant knowledge and would be willing to either lead and/or share your interest on our walks? Contact [email protected]. The February programme is about to go to press. Once again, we are sup- porting the Bristol WalkFest for the month of May - keep a look out for the host of walks that will be on offer, watch this space. Happy walking. The eBoot There will be a new look to the eBoot in 2020, with an increased focus on forthcoming walks and more links to the website, which will hold more de- tails about events and news. -

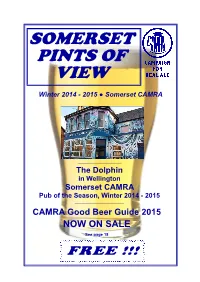

Pints of View Winter 2014-15.Pub

SOMERSET PINTS OF VIEW Winter 2014 - 2015 ● Somerset CAMRA -__________________________________________________________ The Dolphin in Wellington Somerset CAMRA Pub of the Season, Winter 2014 - 2015 __________________________________________________________________ CAMRA GooD Beer GuiDe 2015 NOW ON SALE See page 18 FREE !!! CAMPAIGN FOR REAL ALE 230 Hatfield Road, St Albans, Hertfordshire, AL1 4LW Telephone 01727 867201; www.Camra.org.uk SOMERSET BRANCH BRANCH DIARY 2014 --- 2015 MonDay, December 8 Christmas Social, Ring of Bells 8.00 pm Taunton, TA1 1JS MonDay, January 12 Meeting, The Winchester Arms 8.00 pm Trull, TA3 7LG MonDay, February 9 Meeting, The 37 Club 8.00 pm Puriton, TA7 8AD Website www.somerset.camra.org.uk BRANCH CONTACTS BRANCH CHAIRMAN: Phil Emond. Tel 01823 277038 BRANCH SECRETARY AND CONTACT: Katie Redgate, Tel: 01823 279962. E-mail: [email protected] NEWSLETTER EDITOR: Alan Walker. Tel: 01823 330364. E-mail: [email protected] Vice Chairman: Paul Davey 01935 329975; Social Secretary: John Hesketh 01278 663764; What’s Brewing Contact: John Hesketh 01278 663764; Treasurer: Sally Davey 01935 329975; Membership Secretary: Stephen Walker 01823 413988; Newsletter Ads: Paul Davey 01935 329975; Tasting Panel Co-ordinator: Position Currently vaCant; Public Transport, Discounts, LocAle anD Real CiDer Promotion: Phil Emond 01823 277038; Pubs Officer: Barrie Childs 01823 323642; WhatPub Officer: Andy Jones, e-mail [email protected] Branch Website: Colin Heapy, e-mail: [email protected] PINTS OF VIEW Somerset Pints of View is published by the Somerset BranCh of the Campaign For Real Ale Ltd (CAMRA) and the views expressed herein are not necessarily those of the Campaign or the Editor.