Divergence and Convergence in Spanish Classical and Flamenco Guitar Traditions (1850- 2016): a Dissertation Comprising 2 CD Recital Recordings and Exegesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rhythmic Foundation and Accompaniment

Introduction To Flamenco: Rhythmic Foundation and Accompaniment by "Flamenco Chuck" Keyser P.O. Box 1292 Santa Barbara, CA 93102 [email protected] http://users.aol.com/BuleriaChk/private/flamenco.html © Charles H. Keyser, Jr. 1993 (Painting by Rowan Hughes) Flamenco Philosophy IA My own view of Flamenco is that it is an artistic expression of an intense awareness of the existential human condition. It is an effort to come to terms with the concept that we are all "strangers and afraid, in a world we never made"; that there is probably no higher being, and that even if there is he/she (or it) is irrelevant to the human condition in the final analysis. The truth in Flamenco is that life must be lived and death must be faced on an individual basis; that it is the fundamental responsibility of each man and woman to come to terms with their own alienation with courage, dignity and humor, and to support others in their efforts. It is an excruciatingly honest art form. For flamencos it is this ever-present consciousness of death that gives life itself its meaning; not only as in the tragedy of a child's death from hunger in a far-off land or a senseless drive-by shooting in a big city, but even more fundamentally in death as a consequence of life itself, and the value that must be placed on life at each moment and on each human being at each point in their journey through it. And it is the intensity of this awareness that gave the Gypsy artists their power of expression. -

La Variación Musical En El Mundo Hispánico: La Pete- Nera Mexicana Y La Petenera Flamenca

La variación musical en el mundo hispánico: la pete- nera mexicana y la petenera flamenca Patricia Luisa Hinjos Selfa Instituto Cervantes de Sofía FICHA DE LA ACTIVIDAD Objetivos: – Conocer la música y canciones tradicionales y populares del folklore his- pano. – Establecer diferencias y similitudes entre el folklore de España y de México en un contexto de actualidad. – Ampliar los conocimientos de la cultura hispánica en su diversidad de ma- nifestaciones. – Conocer algunos rasgos lingüísticos dialectales de México y de Andalucía. Nivel recomendado: B2/C1 (MCER). Duración: 3 horas. Dinámica: estudiantes adultos de cursos generales de ELE, diversidad de lenguas y culturas de origen, grupo de 10 alumnos (recomendado). Materiales: vídeos de peteneras, letras de las canciones, fotografías, fichas y textos informativos. 72 1. CONTENIDOS SOBRE LA VARIACIÓN LINGÜÍSTICA Y/O CULTURALEN ESTA ACTIVIDAD SE TRABAJARÁN LOS DOS TIPOS DE VARIACIÓN: – Variación cultural: existencia de variación musical y folclórica en el mundo hispano: algunos géneros. En concreto, la petenera flamenca y la petenera mexicana (huasteca). Música, letras y temas. – Variación lingüística: algunos rasgos fonéticos del español de Andalucía y del español de México. Actividad 1 Activar los conocimientos sobre música popular de España y México. Esta acti- vidad se realizará en dos fases: primero, se responderá individualmente al cuestio- nario y, después, se comparan las respuestas en pequeños grupos (3 o 4 alumnos). Ficha 1 Solución y retroalimentación: comprobación y comentarios en el pleno de la clase, con ampliación de información. Actividad 2 Concretar ideas y conocimientos a través de la identificación y comentario de imágenes. Los alumnos, en parejas preferentemente, intentarán descubrir el país o zona de origen de las fotos, poniéndoles un título adecuado, independientemente de si saben o no de que género se trata en cada caso. -

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

Classical Guitar Music by Irish Composers: Performing Editions and Critical Commentary

L , - 0 * 3 7 * 7 w NUI MAYNOOTH OII» c d I »■ f£ir*«nn WA Huad Classical Guitar Music by Irish Composers: Performing Editions and Critical Commentary John J. Feeley Thesis submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth as fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music (Performance) 3 Volumes Volume 1: Text Department of Music NUI Maynooth Head of Department: Professor Gerard Gillen Supervisor: Dr. Barra Boydell May 2007 VOLUME 1 CONTENTS ABSTRACT i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1 13 APPROACHES TO GUITAR COMPOSITION BY IRISH COMPOSERS Historical overview of the guitar repertoire 13 Approaches to guitar composition by Irish composers ! 6 CHAPTER 2 31 DETAILED DISCUSSION OF SEVEN SELECTED WORKS Brent Parker, Concertino No. I for Guitar, Strings and Percussion 31 Editorial Commentary 43 Jane O'Leary, Duo for Alto Flute and Guitar 52 Editorial Commentary 69 Jerome de Bromhead, Gemini 70 Editorial Commentary 77 John Buckley, Guitar Sonata No. 2 80 Editorial Commentary 97 Mary Kelly, Shard 98 Editorial Commentary 104 CONTENTS CONT’D John McLachlan, Four pieces for Guitar 107 Editorial Commentary 121 David Fennessy, ...sting like a bee 123 Editorial Commentary 134 CHAPTER 3 135 CONCERTOS Brent Parker Concertino No. 2 for Guitar and Strings 135 Editorial Commentary 142 Jerome de Bromhead, Concerto for Guitar and Strings 148 Editorial Commentary 152 Eric Sweeney, Concerto for Guitar and Strings 154 Editorial Commentary 161 CHAPTER 4 164 DUOS Seoirse Bodley Zeiten des Jahres for soprano and guitar 164 Editorial -

Rippling Notes” to the Federal Way Performing Arts & Event Center Sunday, September 17 at 3:00 Pm

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MEDIA CONTACT August 23, 2017 Scott Abts Marketing Coordinator [email protected] DOWNLOAD IMAGES & VIDEO HERE 253-835-7022 MASTSER TIMPLE MUSICIAN GERMÁN LÓPEZ BRINGS “RIPPLING NOTES” TO THE FEDERAL WAY PERFORMING ARTS & EVENT CENTER SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 17 AT 3:00 PM The Performing Arts & Event Center of Federal Way welcomes Germán (Pronounced: Herman) López, Sunday, September 17 at 3:00 PM. On stage with guitarist Antonio Toledo, Germán harnesses the grit of Spanish flamenco, the structure of West African rhythms, the flourishing spirit of jazz, and an innovative 21st century approach to performing “island music.” His principal instrument is one of the grandfathers of the ‘ukelele’, and part of the same instrumental family that includes the cavaquinho, the cuatro and the charango. Germán López’s music has been praised for “entrancing” performances of “delicately rippling notes” (Huffington Post), notes that flow from musical traditions uniting Spain, Africa, and the New World. The “timple” is a diminutive 5 stringed instrument intrinsic to music of the Canary Islands. Of all the hypotheses that exist about the origin of the “timple”, the most widely accepted is that it descends from the European baroque guitar, smaller than the classical guitar, and with five strings. Tickets for Germán López are on sale now at www.fwpaec.org or by calling 2535-835-7010. The Performing Arts and Event Center is located at 31510 Pete von Reichbauer Way South, Federal Way, WA 98003. We’ll see you at the show! About the PAEC The Performing Arts & Event Center opened August of 2017 as the South King County premier center for entertainment in the region. -

Negotiating the Self Through Flamenco Dance

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Anthropology Theses Department of Anthropology 12-2009 Embodied Identities: Negotiating the Self through Flamenco Dance Pamela Ann Caltabiano Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/anthro_theses Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Caltabiano, Pamela Ann, "Embodied Identities: Negotiating the Self through Flamenco Dance." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/anthro_theses/33 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Anthropology at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EMBODIED IDENTITIES: NEGOTIATING THE SELF THROUGH FLAMENCO DANCE by PAMELA ANN CALTABIANO Under the Direction of Emanuela Guano ABSTRACT Drawing on ethnographic research conducted in Atlanta, this study analyzes how transnational practices of, and discourse about, flamenco dance contribute to the performance and embodiment of gender, ethnic, and national identities. It argues that, in the context of the flamenco studio, women dancers renegotiate authenticity and hybridity against the backdrop of an embodied “exot- ic” passion. INDEX WORDS: Gender, Dance, Flamenco, Identity, Exoticism, Embodiment, Performance EMBODIED IDENTITIES: NEGOTIATING THE SELF THROUGH FLAMENCO DANCE by PAMELA ANN -

Téléphone: (0034) 91 5427251 - Nous Exportons Le Flamenco Au Monde Entier

- Ritmo flamenco rhythm (10 CDs + 1 DVD) Téléphone: (0034) 91 5427251 - Nous exportons le Flamenco au monde entier. - Chansons: Disque 1 1. Tarantos 2. Tarantos sin taconeo 3. Tarantos sin guitarra 4. Tarantos sin cante 5. Ritmo de tarantos 6. Tangos 7. Tangos sin taconeo 8. Tangos sin guitarra 9. Tangos sin cante 10. Ritmo de tangos 11. Pista de vídeo (baile) Disque 2 1. Alegrías 2. Alegrías sin taconeo 3. Alegrías sin guitarra 4. Alegrías sin cante 5. Ritmo de alegrías 6. Bulerías de Cádiz 7. Bulerías de Cádiz sin taconeo 8. Bulerías de Cádiz sin guitarra 9. Bulerías de Cádiz sin cante 10. Ritmo de bulerías de Cádiz 11. Pista de vídeo (baile) Disque 3 1. Alboreá 2. Alboreá sin taconeo 3. Alboreá sin guitarra 4. Alboreá sin cante 5. Ritmo de alboreá 6. Peteneras 7. Peteneras sin taconeo 8. Peteneras sin guitarra 9. Peteneras sin cante 10. Ritmo de peteneras (baile) 11. Pista de vídeo (baile) Disque 4 1. Soleá por bulerías 2. Soleá por bulerías sin taconeo 3. Soleá por bulerías sin guitarra 4. Soleá por bulerías sin cante 5. Ritmo de soleá por bulerías 6. Bulerías 7. Bulerías sin taconeo 8. Bulerías sin guitarra 9. Bulerías sin cante 10. Ritmo de bulerías Disque 5 1. Soleá 2. Soleá sin taconeo 3. Ritmo de soleá 4. Seguiriya 5. Seguiriya sin taconeo 6. Ritmo de Seguiriya 7. Pista de vídeo (Baile) Disque 6 1. Seguiriya 2. Seguiriya sin taconeo 3. Seguiriya sin guitarra 4. Seguiriya sin cante 5. Ritmo de seguiriya 6. Farruca 7. Farruca sin taconeo 8. -

Guitar Best Practices Years 1, 2, 3 and 4 Nafme Council for Guitar

Guitar Best Practices Years 1, 2, 3 and 4 Many schools today offer guitar classes and guitar ensembles as a form of music instruction. While guitar is a popular music choice for students to take, there are many teachers offering instruction where guitar is their secondary instrument. The NAfME Guitar Council collaborated and compiled lists of Guitar Best Practices for each year of study. They comprise a set of technical skills, music experiences, and music theory knowledge that guitar students should know through their scholastic career. As a Guitar Council, we have taken careful consideration to ensure that the lists are applicable to middle school and high school guitar class instruction, and may be covered through a wide variety of method books and music styles (classical, country, folk, jazz, pop). All items on the list can be performed on acoustic, classical, and/or electric guitars. NAfME Council for Guitar Education Best Practices Outline for a Year One Guitar Class YEAR ONE - At the completion of year one, students will be able to: 1. Perform using correct sitting posture and appropriate hand positions 2. Play a sixteen measure melody composed with eighth notes at a moderate tempo using alternate picking 3. Read standard music notation and play on all six strings in first position up to the fourth fret 4. Play melodies in the keys C major, a minor, G major, e minor, D major, b minor, F major and d minor 5. Play one octave scales including C major, G major, A major, D major and E major in first position 6. -

Towards an Ethnomusicology of Contemporary Flamenco Guitar

Rethinking Tradition: Towards an Ethnomusicology of Contemporary Flamenco Guitar NAME: Francisco Javier Bethencourt Llobet FULL TITLE AND SUBJECT Doctor of Philosophy. Doctorate in Music. OF DEGREE PROGRAMME: School of Arts and Cultures. SCHOOL: Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences. Newcastle University. SUPERVISOR: Dr. Nanette De Jong / Dr. Ian Biddle WORD COUNT: 82.794 FIRST SUBMISSION (VIVA): March 2011 FINAL SUBMISSION (TWO HARD COPIES): November 2011 Abstract: This thesis consists of four chapters, an introduction and a conclusion. It asks the question as to how contemporary guitarists have negotiated the relationship between tradition and modernity. In particular, the thesis uses primary fieldwork materials to question some of the assumptions made in more ‘literary’ approaches to flamenco of so-called flamencología . In particular, the thesis critiques attitudes to so-called flamenco authenticity in that tradition by bringing the voices of contemporary guitarists to bear on questions of belonging, home, and displacement. The conclusion, drawing on the author’s own experiences of playing and teaching flamenco in the North East of England, examines some of the ways in which flamenco can generate new and lasting communities of affiliation to the flamenco tradition and aesthetic. Declaration: I hereby certify that the attached research paper is wholly my own work, and that all quotations from primary and secondary sources have been acknowledged. Signed: Francisco Javier Bethencourt LLobet Date: 23 th November 2011 i Acknowledgements First of all, I would like to thank all of my supervisors, even those who advised me when my second supervisor became head of the ICMuS: thank you Nanette de Jong, Ian Biddle, and Vic Gammon. -

John Griffiths, Vihuela Vihuela Hordinaria & Guitarra Española

John Griffiths, vihuela 7:30 pm, Thursday April 14, 2016 St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church Miami, Florida Society for Seventeenth-Century Music Annual Conference Vihuela hordinaria & guitarra española th th 16 and 17 -century music for vihuela and guitar So old, so new Fantasía 8 Luis Milán Fantasía 16 (c.1500–c.1561) Fantasía 11 Counterpoint to die for Fantasía sobre un pleni de contrapunto Enríquez de Valderrábano Soneto en el primer grado (c.1500–c.1557) Fantasía del author Miguel de Fuenllana Duo de Fuenllana (c.1500–1579) Strumming my pain Jácaras Antonio de Santa Cruz (1561–1632) Jácaras Santiago de Murcia (1673–1739) Villanos Francisco Guerau Folías (1649–c.1720) Folías Gaspar Sanz (1640–1710) Winds of change Tres diferencias sobre la pavana Valderrábano Diferencias sobre folias Anon. Diferencias sobre zarabanda John Griffiths is a researcher of Renaissance music and culture, especially solo instrumental music from Spain and Italy. His research encompasses broad music-historical studies of renaissance culture that include pedagogy, organology, music printing, music in urban society, as well as more traditional areas of musical style analysis and criticism, although he is best known for his work on the Spanish vihuela and its music. He has doctoral degrees from Monash and Melbourne universities and currently is Professor of Music and Head of the Sir Zelman Cowen School of Music at Monash University, as well as honorary professor at the University of Melbourne (Languages and Linguistics), and an associate at the Centre d’Etudes Supérieures de la Renaissance in Tours. He has published extensively and has collaborated in music reference works including The New Grove, MGG and the Diccionario de la música española e hispanoamericana. -

FDLI Library

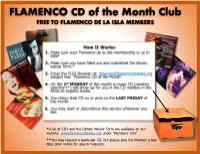

FLAMENCO CD of the Month Club FREE TO FLAMENCO DE LA ISLA MEMBERS *A list of CD’s and the Library Waiver Form are available on our website: www.flamencodelaisla.org under “Members Info” **You may request a particular CD, but please give the librarian a few days prior notice for special requests. FLAMENCO DE LA ISLA SOCIETY RESOURCE LIBRARY DVDs DVD Title: Approx. Details length: Arte y Artistas Flamencos 0:55 Eva La Yerbabuena; Sara Baras; Beatriz Martín Baile Flamenco 1:30 Joaquin Grilo – Romeras; Concha Vargas – Siguiriyas; Maria Pagés – Garrotín; Lalo Tejada – Tientos; Milágros Mengíbar – Tarantos; La Tona – Caracoles; Ana Parilla – Soleares; Carmelilla Montoya - Tangos Bulerías (mixed) 1:22 Caminos Flamenco Vol. 1 1:08 Caminos Flamenco Vol. 2 0:55 Carlos Saura’s Carmen 1:40 Antonio Gades, Laura del Sol, Paco de Lucia Familia Carpio 1:12 Flamenco 1:40 Carlos Saura Flamenco at 5:15 0:30 National Ballet School of Canada Flamenco de la Luz 1:45 Flamenco de la Luz; Una Noche de la Luz; Women artists Gracia del Baile Flamenco 0:40 Gyspy Heart 0:45 Joaquin Cortés y Pasiόn Gitana 1:38 La Chana 0:45 Latcho Drome 1:40 The Life and music of Manuel de Falla 1:15 Montoyas y Tarantos 1:40 Noche Flamenca 0:55 Noche Flamenca Vol. 5 1:00 Nuevo Flamenco Ballet Fury 1:11 Paco Peña’s Misa Flamenco 0:52 "Unique combination of the religious Mass and Flamenco singing and dancing…" [cover] Queen of the Gypsies - Carmen Amaya 1:40 Rito y Geografía del Baile Vol. -

Jazz Standards Arranged for Classical Guitar in the Style of Art Tatum

JAZZ STANDARDS ARRANGED FOR CLASSICAL GUITAR IN THE STYLE OF ART TATUM by Stephen S. Brew Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2018 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Luke Gillespie, Research Director ______________________________________ Ernesto Bitetti, Chair ______________________________________ Andrew Mead ______________________________________ Elzbieta Szmyt February 20, 2018 ii Copyright © 2018 Stephen S. Brew iii To my wife, Rachel And my parents, Steve and Marge iv Acknowledgements This document would not have been possible without the guidance and mentorship of many creative, intelligent, and thoughtful musicians. Maestro Bitetti, your wisdom has given me the confidence and understanding to embrace this ambitious project. It would not have been possible without you. Dr. Strand, you are an incredible mentor who has made me a better teacher, performer, and person; thank you! Thank you to Luke Gillespie, Elzbieta Szmyt, and Andrew Mead for your support throughout my coursework at IU, and for serving on my research committee. Your insight has been invaluable. Thank you to Heather Perry and the staff at Stonehill College’s MacPhaidin Library for doggedly tracking down resources. Thank you James Piorkowski for your mentorship and encouragement, and Ken Meyer for challenging me to reach new heights. Your teaching and artistry inspire me daily. To my parents, Steve and Marge, I cannot express enough thanks for your love and support. And to my sisters, Lisa, Karen, Steph, and Amanda, thank you.