Texas Tech University's Southwest Collection/Special Collections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

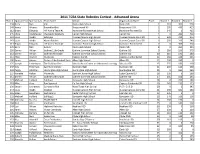

2011 TCEA State Robotics Contest

2011 TCEA State Robotics Contest - Advanced Arena Team # Sponsor First Sponsor Last Team Name School Organization Name Place Round 1 Round 2 Round 3 134 Berry Nall Viki Roma High School Roma ISD 1 510 305 500 148 James Weaver BwoodJediBot Brazoswood HS Brazosport I.S.D. 2 195 430 415 112 Bryan Edwards H-F Arena Team #1 Hamshire-Fannett High School Hamshire-Fannett ISD 3 345 0 425 145 Chris Underwood The Goofy Goobers Carroll High School Carroll ISD 4 0 280 450 142 Louis Webb Sabrijeje Nueces Canyon High School Nueces Canyon Cons ISD 5 390 220 315 143 Louis Webb Alamo Raiders Nueces Canyon High School Nueces Canyon Cons ISD 6 265 315 340 113 Bryan Edwards H-F Arena Team #2 Hamshire-Fannett High School Hamshire-Fannett ISD 7 0 300 350 135 Berry Nall Evolver Roma High School Roma ISD 8 0 265 335 150 Darren Wilson Guthrie 11th Grade Guthrie Common School District Guthrie ISD 9 180 190 375 152 Darren Wilson Guthrie 9th Grade Guthrie Common School District Guthrie ISD 10 315 145 160 147 Allan Warren Mustangs Cypress Ranch Cypress-Fairbanks ISD 11 160 160 295 100 Karen Adams Order of the Painted Rock Allen High School Allen ISD 12 260 180 0 125 Joseph Holochwost The Dubious One Victoria Area Center for Advanced Learning Victoria ISD 13 255 180 160 137 Joey Patterson Aperture Science Burleson High Burleson ISD 14 265 125 160 103 Peggy Albritton Huntington High School Huntington High School Huntington ISD 15 0 160 265 127 Nanette Kelton Mavericks Bonham Junior High School Ector County ISD 16 135 0 280 151 Darren Wilson Guthrie 10th Grade Guthrie Common School District Guthrie ISD 17 245 160 135 123 Michael Holland Bulldog 1 Banquete High School Banquete ISD 18 0 205 190 118 Mike Gray Ron Squared Cy-Fair High School Cypress-Fairbanks ISD 19 245 135 125 130 Steven Livingston Comanche Red West Texas High School P.S.P. -

2018-19 BOARD of DIRECTORS Committee Chairs and Vice Chairs

2018-19 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Committee Chairs and Vice Chairs Jason Roemer Astin Haggerty Brad Blalock President 1st Vice President 2nd Vice President Lake Dallas High School Clear Springs High School Frisco Centennial High School 830-456-4489 281-284-1368 469-633-5600 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Kriss Ethridge Jason Trook Brooke Walthall Past President Reg I, Sr Director Reg I, Jr Director Lubbock Coronado High School Lubbock High School Canyon Randall High School 806-219-1122 806-219-0806 806-677-2333 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Sunni Strickland Mitzi Bell Colby Pastusek Reg II, Sr Director Reg II, Jr Director Reg III, Sr Director Forsan High School Big Spring High School The Colony High School 432-264-3662 512-988-1435 940-232-3392 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Jim Wood Kari Bensend Lindsey Gage Reg III, Jr Director Reg IV, Sr Director Reg IV, Jr Director Maypearl High School Frisco Centennial High School Anna High School 972-435-1020 469-633-5662 903-564-4220 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Jennifer Knight Reagan Smith Brandace Boren Reg V, Sr Director Reg V, Jr Director Reg VI, Sr Director Clear Springs High School Cypress Creek High School Lake Travis High School 409-659-0786 281-795-6544 512-533-6104 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Anthony Branch Bernice Voigt Patti Zenner Reg VI, Jr Director Reg VII, Sr Director Reg VII, Jr Director Sealy High School -

Winners of TMA's Ernest and Sarah Butler Awards for Excellence in Science Teaching

Winners of TMA's Ernest and Sarah Butler Awards for Excellence in Science Teaching Year Elementary School Middle School Sr. High School 2017 First Place: First Place: First Place: Teresa Kelm (Also OVERALL winner) Terri Henry Monica Amyett Connally Elementary Benold Middle School Azle High School Connally Georgetown Azle Second Place: Second Place: Second Place: Therese Ermer Jana Lindley Julieta Banuelas Salinas Elementary Clark Middle School Fabens High School Universal City Abilene Fabens Third Place: Third Place: Third Place: Holly Land Gena Lopez Karey Moore South Bosque Elementary Ennis Jr. High School Aledo High school Woodway Ennis Aledo Rookie Award: Rookie Award: Rookie Award: Lexi Law Brittany Monds Krystal Scott Ben Franklin Elementary Clarendon Jr. High School Goodrich ISD Wichita Falls Clarendon Goodrich 2016 First Place: First Place: First Place: Lauren Paquette Nancy Brown Kenric Davies Hobby Elementary Charles Baxter Junior high School Sherman High School Houston Everman Sherman Second Place: Second Place: Second Place: Marisol Rodriguez Chelsea Atwell Finny Philip Tisinger Elementary Austin Academy for Excellence L.V. Berkner High School Mesquite Garland Richardson 2015 First Place: First Place: First Place: Patricia Kassir Joseph Morris Anna Loonam The Bendwood School All Saint's Episcopal School Bellaire High School Houston Fort Worth Bellaire Second Place: Second Place: Second Place: Laura Wilbanks Carol Raymond Theresa Lawrence Whiteface Elementary EA Young Academy Friendswood High School Whiteface North Richland -

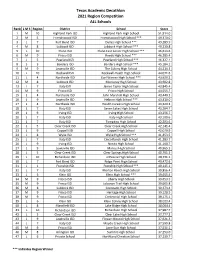

2020-2021 State Scores

Texas Academic Decathlon 2021 Region Competition ALL Schools Rank L M S Region District School Score 1M 10 Highland Park ISD Highland Park High School 51,914.0 2M 5 Friendswood ISD Friendswood High School *** 49,370.0 3L 7 Fort Bend ISD Dulles High School *** 49,289.9 4M 8 Lubbock ISD Lubbock High School *** 49,230.8 5L 10 Plano ISD Plano East Senior High School *** 46,613.6 6M 9 Frisco ISD Reedy High School *** 46,385.4 7L 5 Pearland ISD Pearland High School *** 46,327.1 8S 3 Bandera ISD Bandera High School *** 45,184.1 9M 9 Lewisville ISD The Colony High School 44,214.3 10 L 10 Rockwall ISD Rockwall‐Heath High School 44,071.6 11 L 4 Northside ISD Earl Warren High School *** 43,929.2 12 M 8 Lubbock ISD Monterey High School 43,902.8 13 L 7 Katy ISD James Taylor High School 43,845.4 14 M 9 Frisco ISD Frisco High School 43,555.7 15 L 4 Northside ISD John Marshall High School 43,440.3 16 L 9 Lewisville ISD Hebron High School *** 43,410.0 17 L 4 Northside ISD Health Careers High School 43,320.3 18 L 7 Katy ISD Seven Lakes High School 43,264.7 19 L 9 Irving ISD Irving High School 43,256.7 20 L 7 Katy ISD Katy High School 43,109.6 21 L 7 Katy ISD Tompkins High School 42,203.6 22 L 5 Clear Creek ISD Clear Creek High School 42,141.4 23 L 9 Coppell ISD Coppell High School 42,070.9 24 L 8 Wylie ISD Wylie High School *** 41,453.5 25 L 7 Katy ISD Cinco Ranch High School 41,283.7 26 L 9 Irving ISD Nimitz High School 41,160.7 27 L 9 Lewisville ISD Marcus High School 40,965.3 28 L 5 Clear Creek ISD Clear Springs High School 40,761.3 29 L 10 Richardson -

College and Career Ready Generation

COLLEGE AND CAREER READY GENERATION High School Handbook 2016-2017 2016 - 2017 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................ 1-2 High School Information ......................................................................................... 3-5 Graduation Requirements .................................................................................... 6-14 2017 Graduates .......................................................................................... 8-10 2018 and Beyond Graduates ..................................................................... 11-14 Acknowledgements of Advanced Measures and Performance ............................................................................................. 15-16 General Four-Year Plan .................................................................................. 17 High School Testing ............................................................................................ 18-30 End of Course Exams ..................................................................................... 19 TSI ............................................................................................................. 20-21 PSAT 8/9 ......................................................................................................... 22 PSAT/NMSQT ................................................................................................. 23 SAT and SAT Subject Tests ...................................................................... -

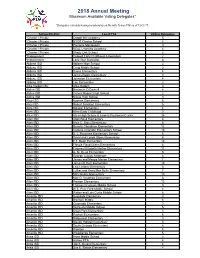

2018 Annual Meeting Maximum Available Voting Delegates*

2018 Annual Meeting Maximum Available Voting Delegates* *Delegates calculated using membership on file with Texas PTA as of 12/01/17. School District Local PTA Voting Delegates *Charter / Private Chapel Hill Academy 5 *Charter / Private NYOS Charter School 2 *Charter / Private Pinnacle Montessori 3 *Charter / Private REAL Learning Academy 4 *Charter / Private Shady Oak School 2 *Independent Coppell Early Childhood Association 2 *Independent Lone Star Statewide 8 Abilene ISD Abilene High School 3 Abilene ISD Craig Middle School 2 Abilene ISD Dyess Elementary 4 Abilene ISD James Bowie Elementary 3 Abilene ISD Johnston Elementary 4 Abilene ISD Lee Elementary 2 Alba-Golden ISD Alba-Golden 3 Aldine ISD Benjamin O Davis 9 4 Aldine ISD Carver Magnet High School 2 Aldine ISD Nimitz High School 3 Alice ISD Noonan Elementary 5 Alice ISD Robert Schallert Elementary 5 Alice ISD Salazar Elementary 4 Allen ISD Allen Early Childhood 3 Allen ISD Allen High School & Lowery Freshman Center 16 Allen ISD Alton Boyd Elementary 4 Allen ISD Alvis C. Story Elementary 8 Allen ISD Beverly Cheatham Elementary 12 Allen ISD Carlena Chandler Elementary School 10 Allen ISD D. L. Rountree Elementary School 4 Allen ISD David and Lynda Olson Elementary 8 Allen ISD E.T. Boon Elementary 10 Allen ISD Flossie Floyd Green Elementary 8 Allen ISD Frances Elizabeth Norton Elementary 11 Allen ISD G. M. Reed Elementary 5 Allen ISD George Julious Anderson 8 Allen ISD James and Margie Marion Elementary 7 Allen ISD James D. Kerr Elementary 10 Allen ISD Lois Lindsey Elementary 8 Allen ISD Luther and Anna Mae Bolin Elementary 7 Allen ISD Mary Evans Elementary 10 Allen ISD Max O. -

Texas Forensic Association Constitution and Contest Rules Revised April 2020

Texas Forensic Association Constitution and Contest Rules Revised April 2020 The purpose of the Texas Forensic Association is to bring about more effective cooperation among the members of the speech and theatre arts profession in the discharge of their special responsibilities in forensic and theatre activities; to create a means of educating the general and professional publics to the important educational functions of forensics and theatre arts; to make collective action possible on problems of common professional interest; and, in general, to maintain and advance the ideals and standards of the speech and theatre arts profession. The Texas Forensic Association shall promote the interests of interscholastic speech and theatre by encouraging a spirit of fellowship among participating students and teachers. Activities viewed as central to the organization’s function include debate, theatre, and competitive individual speaking events. The Association continues to set high standards and strives to meet new goals for the benefit of Texas Teachers and students. The model of the Texas Forensic Association has been recommended for other states where similar needs are felt. 1 Table of Contents Contents Constitution ............................................................................................................................................ 6 Article 1. Name .................................................................................................................................... 6 Article II. Purpose ................................................................................................................................ -

This'll Be the Day.P65

Rock the Halls with Bows of Holly 1 Part One: Stairway to Whatever 1. Rock the Halls with Bows of Holly “The levee ain’t dry, And the music didn’t die, ‘Cause Buddy Holly lives Every time we play rock and roll.” —Cricket bandmate Sonny Curtis, 1980 This is a book mostly about Buddy Holly. And his Crickets. The world knows Buddy as the martyred hero of “American Pie,” Don McLean’s #1 rockin’ 1971 saga of dry levees, roaring Chevys, and a golden-age America when rock was young. Long before leaded Zeppelin dreams soared aloft to the stars on ‘Stairways to Heaven,’ rock and roll first honored lean Texan Buddy Holly with his fiery Fender Stratocaster and magic voice. Holly and his rockin’ Crickets brought 1957-59 America and the English-speaking world its first torrid affair with a genuine rock and roll band. After Elvis This’ll Be The Day 2 Presley’s vocals, Chuck Berry’s lead guitar and teen lyrics, and dozens of dynamic drummers perfo- rated 50s quietude with new molten music, Buddy’s electric guitar and bass-powered rock band the Crickets gave us our first taste of rock band glory. Buddy also jump-started the Beatles and Bob Dylan. And yes, of course, the Fab Four owe the Crickets for their style, their gung-ho gusto, and their name. By now, the Beatles’ reputation as premier rock band has never been higher. This’ll Be the Day is about the world’s first and the world’s greatest rock and roll band. -

Texas Association of Basketball Coaches

TEXAS ASSOCIATION OF BASKETBALL COACHES TABC Past President’s Bios and Pictures Tommy Newman 1975-77 Tommy Newman retired in 2006 after 38 years in education, the first 30 as a basketball coach. Tommy coached at the high school level at Arlington Heights, F.W. Poly, Richland and Euless Trinity. In 18 years as a head coach his teams were district champs 11 times, appeared in five regional tournaments and one final four. He also coached for ten years in the college level as an assistant at Baylor and head coach at Texas Wesleyan and North Texas. His 1982 TWC team won 30 games and qualified for the NAIA national tournament. Tommy was an all-state player at F.W. Paschal and played on a final four team at Wichita State. He was elected to the Texas High School Basketball Hall of Fame in 2001. Kenneth Cleveland 1977-78 Ken Cleveland starred at Coleman High School and the University of Texas, graduating in 1958. After three years as head coach at Sonora, Ken became varsity coach at Dimmitt where he built a dynasty. During his 32 years the Bobcats won 27 district titles, 10 regional championships and state titles in 1975, ’82 and ’83. Coach Cleveland was inducted into the Texas High School Basketball Hall of Fame and the THSCA Hall of Honor. Ken’s life was cut short when he was struck by lightning in 1993. He is survived by his wife Libby and daughters Beth, Vicki and son Kevin. His career head coaching record is 887-277. Mike Smith 1978-79 Mike Smith was the head boys basketball coach in Victoria from 1972-1998 where he led the Stingarees to 21 playoff appearances, 17 district titles, 10 regional tournaments, and two final fours. -

CSA 2019 Winners Spreadsheet

Texas College Success Award-Winning Schools Total % Low-income School City Award year(s) Type enrollment students Aldine Independent School District Victory Early College High School Houston 2019 Public district 449 80% Aledo Independent School District Aledo High School Aledo 2019 Public district 1,168 9% Alief Independent School District Kerr High School Houston 2019 Public district 809 61% Alpine Independent School District Alpine High School Alpine 2019 Public district 292 38% Amarillo Independent School District Amarillo High School Amarillo 2019 Public district 2,140 20% Archer City Independent School District Archer City High School Archer City 2019 Public district 213 29% Argyle Independent School District Argyle High School Argyle 2019 Public district 751 8% Arlington Independent School District Martin High School Arlington 2019 Public district 3,351 27% Austin Independent School District Anderson High School Austin 2019 Public district 2,270 23% Bowie High School Austin 2019 Public district 2,912 12% Lasa High School Austin 2019 Public district 1,016 9% Richards School For Young Women Leade Austin 2019 Public district 787 58% Austwell-Tivoli Independent School District Austwell-Tivoli High School Tivoli 2019 Public district 73 56% Avalon Independent School District Avalon School Avalon 2019 Public district 379 55% Baird Independent School District Baird High School Baird 2019 Public district 91 63% Beckville Independent School District Beckville Jr-Sr High School Beckville 2019 Public district 373 34% Bells Independent School -

Qualifiers to Round 2

PLEASE NOTE: The films are numbered to make it easier to find projects in the list, it is not indicative of ranking. Division 1 includes schools in the 1A-4A conference. Division 2 includes schools in the 5A and 6A conference. Division 1 Digital Animation 1. Pulse Argyle High School, Argyle 2. Waiting for Love Argyle High School, Argyle 3. Another World Bishop High School, Bishop 4. Bubblegum Rock Callisburg High School, Callisburg 5. The Red Yarn Celina High School, Celina 6. Garden Celina High School, Celina 7. Sketchy Celina High School, Celina 8. Blimp and Crunch Dublin High School, Dublin 9. Penguins Hallettsville High School, Hallettsville 10. Joy Ride Kenedy High School, Kenedy 11. The Struggle Is Real Kenedy High School, Kenedy 12. Danasaur: A Story Lampasas High School, Lampasas 13. Fungy Business Lampasas High School, Lampasas 14. Behind Closed Doors Lampasas High School, Lampasas 15. Two Dimensional Lindsay High School, Lindsay 16. Mirror, Mirror Melissa High School, Melissa 17. Hare New Tech HS, Manor 18. The Guiding Spirit New Tech HS, Manor 19. Streetlight Sabine Pass High School, Sabine Pass 20. Catpucchino Salado High School, Salado 21. Noitroba San Augustine High School, San Augustine 22. Angels & Demons Stephenville High School, Stephenville 23. To - Do Sunnyvale High School, Sunnyvale 24. Pop Yoakum High School, Yoakum Division 1 Documentary 1. New Mexico Magic, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Andrews High School, Andrews 2. Ukrainian Beauty Argyle High School, Argyle 3. Angels of Mercy Argyle High School, Argyle 4. They're Watching Us Argyle High School, Argyle 5. "I Can Do It" Blanco High School, Blanco 6. -

2016 Texas High School State Championships

Lee & Joe Jamail Texas Swimming Center - Site License HY-TEK's MEET MANAGER 6.0 - 9:55 PM 2/7/2016 Page 1 2016 5A State Meet - 2/19/2016 to 2/20/2016 Qualifiers - 5A Event 1 Girls 200 Yard Medley Relay Team Relay Seed Time 1 Frisco 1:48.24 2 Cedar Park High School 1:49.00 3 Kingwood Park 1:49.89 4 El Paso High 1:50.25 5 Alamo Heights-ST 1:51.60 6 Houston Stratford 1:51.69 7 Texarkana Texas 1:55.21 8 Mansfield Lake Ridge 1:56.97 Event 2 Boys 200 Yard Medley Relay Team Relay Seed Time 1 Frisco 1:36.96 2 A&M Consolidated High School 1:37.04 3 Texarkana Texas 1:38.88 4 Grapevine High 1:38.99 5 Alamo Heights-ST 1:39.92 6 Houston Stratford 1:40.23 7 Lubbock High School 1:40.31 8 Kingwood Park 1:41.03 Event 3 Girls 200 Yard Freestyle Name Year School Seed Time 1 Haley Yelle 11 Mansfield Legacy 1:48.33 2 Gabrielle Kopenski 10 Prosper High School 1:48.73 3 Joy Field 11 Magnolia High School 1:49.94 4 Ellery Parish 11 Alamo Heights-ST 1:52.58 5 Alejandra Acosta 12 El Paso Jeff_Silva-BD 1:54.95 6 Holly Ratcliff 12 Hudson 1:56.39 7 Emma Bleasdell 9 Ridge Point High School 1:57.26 8 Erika Stephenson 12 Houston Stratford 1:57.46 Event 4 Boys 200 Yard Freestyle Name Year School Seed Time 1 Samuel Kline 12 Frisco Wakeland 1:38.32 2 Mitchell Upchurch 12 Samuel V Champion HS 1:41.70 3 John Winkler 11 Vandegrift High School 1:42.69 4 Brandon Baron JR Fort Worth Arlington Heights 1:43.03 5 Kolos Nagy 9 Lubbock High School 1:46.62 6 Matthew Gaas 11 Richmond Foster 1:46.72 7 Michael Maly 12 White Oak 1:46.77 8 Andrew McClellan 11 New Caney 1:46.91 Event 5 Girls 200 Yard IM Name Year School Seed Time 1 Lindsay Looney 09 Denison High School 2:01.71 2 Jessica Peng 09 A&M Consolidated High School 2:06.97 3 Rebecca Brandt 11 Dallas Hillcrest 2:08.61 4 Grace Strash 11 Alamo Heights-ST 2:12.35 5 Madison Chao 12 Grapevine High 2:12.84 6 Andrea Acosta 10 El Paso Jeff_Silva-BD 2:12.93 Lee & Joe Jamail Texas Swimming Center - Site License HY-TEK's MEET MANAGER 6.0 - 9:55 PM 2/7/2016 Page 2 2016 5A State Meet - 2/19/2016 to 2/20/2016 Qualifiers - 5A Event 5 ..