New Jersey's Barrier Islands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEW JERSEY History GUIDE

NEW JERSEY HISTOry GUIDE THE INSIDER'S GUIDE TO NEW JERSEY'S HiSTORIC SitES CONTENTS CONNECT WITH NEW JERSEY Photo: Battle of Trenton Reenactment/Chase Heilman Photography Reenactment/Chase Heilman Trenton Battle of Photo: NEW JERSEY HISTORY CATEGORIES NEW JERSEY, ROOTED IN HISTORY From Colonial reenactments to Victorian architecture, scientific breakthroughs to WWI Museums 2 monuments, New Jersey brings U.S. history to life. It is the “Crossroads of the American Revolution,” Revolutionary War 6 home of the nation’s oldest continuously Military History 10 operating lighthouse and the birthplace of the motion picture. New Jersey even hosted the Industrial Revolution 14 very first collegiate football game! (Final score: Rutgers 6, Princeton 4) Agriculture 19 Discover New Jersey’s fascinating history. This Multicultural Heritage 22 handbook sorts the state’s historically significant people, places and events into eight categories. Historic Homes & Mansions 25 You’ll find that historic landmarks, homes, Lighthouses 29 monuments, lighthouses and other points of interest are listed within the category they best represent. For more information about each attraction, such DISCLAIMER: Any listing in this publication does not constitute an official as hours of operation, please call the telephone endorsement by the State of New Jersey or the Division of Travel and Tourism. numbers provided, or check the listed websites. Cover Photos: (Top) Battle of Monmouth Reenactment at Monmouth Battlefield State Park; (Bottom) Kingston Mill at the Delaware & Raritan Canal State Park 1-800-visitnj • www.visitnj.org 1 HUnterdon Art MUseUM Enjoy the unique mix of 19th-century architecture and 21st- century art. This arts center is housed in handsome stone structure that served as a grist mill for over a hundred years. -

68: Protest, Policing, and Urban Space by Hans Nicholas Sagan A

Specters of '68: Protest, Policing, and Urban Space by Hans Nicholas Sagan A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Galen Cranz, Chair Professer C. Greig Crysler Professor Richard Walker Summer 2015 Sagan Copyright page Sagan Abstract Specters of '68: Protest, Policing, and Urban Space by Hans Nicholas Sagan Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Berkeley Professor Galen Cranz, Chair Political protest is an increasingly frequent occurrence in urban public space. During times of protest, the use of urban space transforms according to special regulatory circumstances and dictates. The reorganization of economic relationships under neoliberalism carries with it changes in the regulation of urban space. Environmental design is part of the toolkit of protest control. Existing literature on the interrelation of protest, policing, and urban space can be broken down into four general categories: radical politics, criminological, technocratic, and technical- professional. Each of these bodies of literature problematizes core ideas of crowds, space, and protest differently. This leads to entirely different philosophical and methodological approaches to protests from different parties and agencies. This paper approaches protest, policing, and urban space using a critical-theoretical methodology coupled with person-environment relations methods. This paper examines political protest at American Presidential National Conventions. Using genealogical-historical analysis and discourse analysis, this paper examines two historical protest event-sites to develop baselines for comparison: Chicago 1968 and Dallas 1984. Two contemporary protest event-sites are examined using direct observation and discourse analysis: Denver 2008 and St. -

INVENTORY of Tpf Larrier ISLAND CHAIN of the STATES of NEW YORK and NEW JERSEY

B250B50 SCH INVENTORY OF TPf lARRIER ISLAND CHAIN OF THE STATES OF NEW YORK AND NEW JERSEY PREPARED UNDER THE AUSPICES OF THE OPEN SPACE INSTITUTE FUNDED BY THE MC INTOSH FOUNDATION Pr OCL 13;.2 B5D 5ch INVENTORY OF THE BARRIER ISLAND CHAIN OF THE STATES OF NEW YORK AND NEW JERSEY JAMES J, SCHEINKMANJ RESEARCHER PETER M. BYRNEJ CARTOGRAPHER ,, I PREPARED UNDER THE AUSPICES OF THE J OPEN SPACE INSTITUTE 45 Rockefeller Plaza Room 2350 New York, N.Y. 10020 FUNDED BY THE MC INTOSH FOUNDATION October, 1977 I r- I,,' N.J~...; OCZ[VJ dbrary We wish to thank John R. Robinson, 150 Purchase Street, Rye, New York 10580, for his help and guidance and for the use of his office facilities in the prepara tion of this report. Copyright © The Mcintosh Foundation 1977 All rights reserved. Except for use in a review, the reproduction or utilization of this work in any form or by any electronic, mech anical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including xerography, photocopying, and recording, and in any information stor age and retrieval system is forbidden without the written permission of the publisher. TABLE OE' CONTENTS Page Number Preface iv New York Barrier Island Chain: Introduction to the New York Barrier Island Chain NY- 2 Barrier Island (Unnamed) NY- 5 Fire Island NY-10 Jones Beach Island NY-16 Long Beach Island NY-20 Background Information for Nassau County NY-24 Background Information for Suffolk County NY-25 New Jersey Barrier Island Chain: Introduction to the New Jersey Barrier Island Chain NJ- 2 Sandy Hook Peninsula NJ- 5 Barnegat -

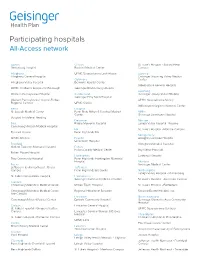

Participating Hospitals All-Access Network

Participating hospitals All-Access network Adams Clinton St. Luke’s Hospital - Sacred Heart Gettysburg Hospital Bucktail Medical Center Campus Allegheny UPMC Susquehanna Lock Haven Luzerne Allegheny General Hospital Geisinger Wyoming Valley Medical Columbia Center Allegheny Valley Hospital Berwick Hospital Center Wilkes-Barre General Hospital UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh Geisinger Bloomsburg Hospital Lycoming Western Pennsylvania Hospital Cumberland Geisinger Jersey Shore Hospital Geisinger Holy Spirit Hospital Western Pennsylvania Hospital-Forbes UPMC Susquehanna Muncy Regional Campus UPMC Carlisle Williamsport Regional Medical Center Berks Dauphin St. Joseph Medical Center Penn State Milton S Hershey Medical Mifflin Center Geisinger Lewistown Hospital Surgical Institute of Reading Delaware Monroe Blair Riddle Memorial Hospital Lehigh Valley Hospital - Pocono Conemaugh Nason Medical Hospital Elk St. Luke’s Hospital - Monroe Campus Tyrone Hospital Penn Highlands Elk Montgomery UPMC Altoona Fayette Abington Lansdale Hospital Uniontown Hospital Bradford Abington Memorial Hospital Guthrie Towanda Memorial Hospital Fulton Fulton County Medical Center Bryn Mawr Hospital Robert Packer Hospital Huntingdon Lankenau Hospital Troy Community Hospital Penn Highlands Huntingdon Memorial Hospital Montour Bucks Geisinger Medical Center Jefferson Health Northeast - Bucks Jefferson Campus Penn Highlands Brookville Northampton Lehigh Valley Hospital - Muhlenberg St. Luke's Quakertown Hospital Lackawanna Geisinger Community Medical Center St. Luke’s Hospital - Anderson Campus Cambria Conemaugh Memorial Medical Center Moses Taylor Hospital St. Luke’s Hospital - Bethlehem Conemaugh Memorial Medical Center - Regional Hospital of Scranton Steward Easton Hospital, Inc. Lee Campus Lancaster Northumberland Conemaugh Miners Medical Center Ephrata Community Hospital Geisinger Shamokin Area Community Hospital Carbon Lancaster General Hospital St. Luke’s Hospital - Gnaden Huetten UPMC Susquehanna Sunbury Campus Lancaster General Women & Babies Hospital Philadelphia St. -

Anthony Bourdain Food Trail Pays Tribute to Bourdain’S Childhood Growing up in Leonia, New 2 Jersey, and Summers Spent at the Jersey Shore

ANTHONY BOURDAIN FOOD TRAIL 1 Discover the New Jersey culinary roots of the late Anthony Bourdain, celebrity chef, best- selling author and globe-trotting food and travel documentarian, on a newly designated food trail. The Anthony Bourdain Food Trail pays tribute to Bourdain’s childhood growing up in Leonia, New 2 Jersey, and summers spent at the Jersey Shore. The trail spotlights 10 New Jersey restaurants featured on CNN’s Emmy Award-winning Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown. 10 9 8 3 “To know Jersey is to love her.” 4 – Anthony Bourdain 7 5 6 Restaurant visitnj.org descriptions on next page NORTH JERSEY 1 Hiram’s Roadstand, Fort Lee “This is my happy place,” said Bourdain about this Fort Lee institution. Hiram’s has been slinging classic “ripper-style” (deep-fried) hot dogs since the 1930s. 1345 Palisade Ave., Fort Lee, NJ 07024 JERSEY SHORE For more information, go to visitnj.org, the official travel 2 Frank’s Deli & Restaurant, Asbury Park site for the State of New Jersey. The place to pick up overstuffed sandwiches on the way to the beach. “As I always like to say, good is good forever,” said Bourdain about Frank’s. Try the classic Jersey sandwich: sliced ham, provolone, tomato, onions, shredded • 130 Miles of Atlantic lettuce, roasted peppers, oil and vinegar. 1406 Main St., Asbury Park, NJ 07712 Coastline • Easy Access to New York 3 Kubel’s, Barnegat Light City and Philadelphia Bourdain grew up eating clams at the Jersey Shore, so this seaside restaurant, • Six Flags Great Adventure a Long Beach Island tradition since 1927, was a natural. -

Longport As Borough ~Htis 66Th Anniversary by FRANK BUTLER This Area to Matthew S

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) r~--v '- •••-' rr» <**"> -.. L_ .. .... United States Department of the Interior ill National Park Service Iwitjl « 5 National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Church of the Redeemer other names/site number N/A 2. Location street & number 2Qt:h & Atlantic Avenues . HS. not for publication city or town __ Longport Borough _ D vicinity state New Jersey code 034 county Atlantic code oni zip code 084Q3 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this S nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property Kl meets D does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Construction Guidelines for Wildlife Fencing and Associated Escape and Lateral Access Control Measures

CONSTRUCTION GUIDELINES FOR WILDLIFE FENCING AND ASSOCIATED ESCAPE AND LATERAL ACCESS CONTROL MEASURES Requested by: American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) Standing Committee on the Environment Prepared by: Marcel P. Huijser, Angela V. Kociolek, Tiffany D.H. Allen, Patrick McGowen Western Transportation Institute – Montana State University PO Box 174250 Bozeman, MT 59717-4250 Patricia C. Cramer 264 E 100 North, Logan, Utah 84321 Marie Venner Lakewood, CO 80232 April 2015 The information contained in this report was prepared as part of NCHRP Project 25-25, Task 84, National Cooperative Highway Research Program, Transportation Research Board. SPECIAL NOTE: This report IS NOT an official publication of the National Cooperative Highway Research Program, Transportation Research Board, National Research Council, or The National Academies. Wildlife Fencing and Associated Measures Disclaimer DISCLAIMER DISCLAIMER STATEMENT The opinions and conclusions expressed or implied are those of the research agency that performed the research and are not necessarily those of the Transportation Research Board or its sponsors. The information contained in this document was taken directly from the submission of the author(s). This document is not a report of the Transportation Research Board or of the National Research Council. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study was requested by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO), and conducted as part of the National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP) Project 25-25 Task 84. The NCHRP is supported by annual voluntary contributions from the state Departments of Transportation. Project 25-25 is intended to fund quick response studies on behalf of the AASHTO Standing Committee on the Environment. -

Download the Gc2040 Brochure (PDF)

Gloucester County Courthouse Woodbury, NJ About DVRPC DVRPC is the federally designated Metropolitan Planning Organization for the Greater Philadelphia Region. For more than 50 years, DVRPC has worked to foster regional cooperation in a nine-county, two-state area: Bucks, Chester, Delaware, Montgomery, and Philadelphia in Pennsylvania; and Burlington, Camden, Gloucester, and Mercer in New Jersey. Through DVRPC, city, county and state representatives work together to address key issues, including transportation, land use, environmental protection and economic development. For more information, please visit: www.dvrpc.org. 190 N. Independence Mall West 8th Floor | Philadelphia, PA 19106 (215) 592-1800 | www.dvrpc.org Photo Credits Gloucester County Courthouse Photo by J. Stephen Conn on Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0) Scotland Run Lake Photo by DVRPC Tour de Pitman Photo by Nhan Nguyen on Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0) Street Clock, Wenonah, NJ Photo by RNWatson, Lindenwold, NJ Whitney Center, Glassboro New Jersey Photo by Rowan University Publications on Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) Welcome to Gloucester County Photo by DVRPC From Vision to Plan Chances are you already know that Gloucester County is a great place to Establishing a community vision is a critical first step in live, do business, and have fun. planning for Gloucester County’s future. Over the next year, Gloucester County and DVRPC will be working After all, Gloucester County combines welcoming together to produce a Unified Land Use and Transportation neighborhoods, dynamic downtowns, and rural farmland all Element for the Gloucester County Master Plan that builds a short distance from Philadelphia. on the principles presented here. -

Jersey Shore Council, Boy Scouts of America Suggested List of Dignitaries to Invite to Your Eagle Court of Honor

JERSEY SHORE COUNCIL, BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA SUGGESTED LIST OF DIGNITARIES TO INVITE TO YOUR EAGLE COURT OF HONOR First - do not start making plans or setting a date for the Eagle Court of Honor until you have received confirmation from the Jersey Shore Council Office that final approval and your certificate have been received from National. We have provided you with a list of Dignitaries you may consider in attendance. Your President and Political Figures may respond with a congratulatory letter or citation. A few may surprise you with a personal appearance. For the Eagle ceremony itself, there are several versions available in a book called "Eagle Ceremonies" at the Council Service Center. Another resource would be our Council Chapter of the "National Eagle Scout Association". Our Council's Representative would be available upon request at the Service Center. Plan your Eagle Court of Honor date at least thirty (30) days after your invitations are ready for mailing. This allows the Dignitaries enough time to R.S.V.P. and reserve the date on their calendar. TITLE NAME ADDRESS U.S. PRESIDENT JOSEPH BIDEN THE WHITE HOUSE SCHEDULING OFFICE 1600 PENNSYLVANIA AVE NW WASHINGTON, D.C. 205000 VICE PRESIDENT KAMALA HARRIS THE WHITE HOUSE VICE PRESIDENT’S SCHEDULING OFFICE 1600 PENNSYLVANIA AVE NW WASHINGTON, DC 20500 June 28, 2021 CONGRESSMAN ANDREW KIM (3RD) 1516 LONGWORTH OFFICE BLDG WASHIINGTON, DC 20515 CONGRESSMAN JEFFERSON VAN DREW (2ND) 5914 MAIN STREET, SUITE 103 MAYS LANDING, NJ 08330 CONGRESSMAN CHRISTOPHER H SMITH (4TH) 405 ROUTE 539 PLUMSTEAD, NJ 08514 SENATOR CORY BOOKER 1 GATEWAY CENTER, 23RD FLOOR NEWARK, NJ 07102 SENATOR ROBERT MENENDEZ 1 GATEWAY CENTER, 11TH FLOOR NEWARK, NJ 07102 GOVERNOR PHIL MURPHY OFFICE OF THE GOVERNOR P.O. -

Cast-In-Place Concrete Barriers

rev. May 14, 2018 Cast-In-Place Concrete Barriers April 23, 2013 NOTE: Reinforcing steel in each of these barrier may vary and have been omitted from the drawings for clarity, only the Ontario Tall Wall was successfully crash tested as a unreinforced section. TEST LEVEL NAME/MANUFACTURER ILLUSTRATION PROFILE GEOMETRIC DIMENSIONS CHARACTERISTICS AASHTO NCHRP 350 MASH New Jersey Safety-Shape Barrier TL-3 TL-3 32" Tall 32" Tall The New Jersey Barrier was the most widely used safety shape concrete barrier prior to the introduction of the F-shape. As shown, the "break-point" between the 55 deg and 84 deg slope is 13 inches above the pavement, including the 3 inch vertical reveal. The flatter lower slope is intended to lift the vehicle which TL-4 TL-4 http://tf13.org/Guides/hardwareGuide/index.php?a absorbs some energy, and allows vehicles impacting at shallow angles to be 32" Tall 36" Tall X ction=view&hardware=111 redirected with little sheet metal damage; however, it can cause significant instability to vehicles impacting at high speeds and angles. Elligibility Letter TL-5 TL-5 B-64 - Feb 14, 2000 (NCHRP 350) 42" Tall 42" Tall NCHRP Project 22-14(03)(MASH TL3) NCHRP 20-07(395) (MASH TL4 & TL5) F-shape Barrier TL-3 TL-3 The F-shape has the same basic geometry as the New Jersey barrier, but the http://tf13.org/Guides/hardwareGuide/index.php?a 32" Tall 32" Tall "break-point" between the lower and upper slopes is 10 inches above the ction=view&hardware=109 pavement. -

New Jersey State Research Guide Family History Sources in the Garden State

New Jersey State Research Guide Family History Sources in the Garden State New Jersey History After Henry Hudson’s initial explorations of the Hudson and Delaware River areas, numerous Dutch settlements were attempted in New Jersey, beginning as early as 1618. These settlements were soon abandoned because of altercations with the Lenni-Lenape (or Delaware), the original inhabitants. A more lasting settlement was made from 1638 to 1655 by the Swedes and Finns along the Delaware as part of New Sweden, and this continued to flourish although the Dutch eventually Hessian Barracks, Trenton, New Jersey from U.S., Historical Postcards gained control over this area and made it part of New Netherland. By 1639, there were as many as six boweries, or small plantations, on the New Jersey side of the Hudson across from Manhattan. Two major confrontations with the native Indians in 1643 and 1655 destroyed all Dutch settlements in northern New Jersey, and not until 1660 was the first permanent settlement established—the village of Bergen, today part of Jersey City. Of the settlers throughout the colonial period, only the English outnumbered the Dutch in New Jersey. When England acquired the New Netherland Colony from the Dutch in 1664, King Charles II gave his brother, the Duke of York (later King James II), all of New York and New Jersey. The duke in turn granted New Jersey to two of his creditors, Lord John Berkeley and Sir George Carteret. The land was named Nova Caesaria for the Isle of Jersey, Carteret’s home. The year that England took control there was a large influx of English from New England and Long Island who, for want of more or better land, settled the East Jersey towns of Elizabethtown, Middletown, Piscataway, Shrewsbury, and Woodbridge. -

Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission Board

DELAWARE VALLEY REGIONAL PLANNING COMMISSION BOARD COMMITTEE Minutes of Meeting of April 28, 2016 Location: Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission 190 N. Independence Mall West Philadelphia, PA 19106 Membership Present Representative New Jersey Department of Community Affairs Sean Thompson New Jersey Department of Transportation Dave Kuhn Pennsylvania Department of Transportation James Mosca New Jersey Governor’s Appointee Chris Howard Pennsylvania Governor's Appointee (not represented) Pennsylvania Governor’s Policy & Planning Office Nedia Ralston Bucks County Lynn Bush Chester County Brian O’Leary Delaware County John McBlain Linda Hill Montgomery County Valerie Arkoosh Jody Holton Burlington County Carol Thomas Camden County Andrew Levecchia Gloucester County (not represented) Mercer County Matthew Lawson City of Chester Latifah Griffin City of Philadelphia Mark Squilla Clarena Tolson Denise Goren City of Camden Dana Redd Edward Williams City of Trenton Jeffrey Wilkerson Non-Voting Members Federal Highway Administration New Jersey Division (not represented) Pennsylvania Division (not represented) U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Region III Richard Ott U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region II (not represented) U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region III (not represented) 1 B-4/28/16 Federal Transit Administration, Region III (not represented) Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority Byron Comati New Jersey Transit Corporation Jennifer Adam New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection