Chippendale Mirror

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exercises in Wood-Working, with a Short Treatise on Wood;

'^^ %."^o* ^r c. .^^~:, "<^^ '^' V ..^"^ .o"^ cO.".-* V^o " A.'^'' ..^'r- v^^ v^' y ,t'», < '-^0^ /. CV « o,. *r;.' aO ^. 'bV" X-O-T- i'^'V. .<•*' • 'VJ"""^^ ' o „ » <vf^ > V »*•»' ^ aO s' EXERCISES IN WOOD-WORKII^G WITH A SHORT TREATISE ON WOOD WRITTEN FOR MANUAL TRAINING GLASSES IN SCHOOLS AND COLLEGES BY IVIN SICKELS, M. S., M. D. ^ NEW YOKE D. APPLETON AND COMPANY 1890 K Copyright, 1889, By D. APPLETON AND COMPAlSfY. i-'3}P') PREFACE. The exercises in wood-working in this book were pre- pared by me during the summer of 1883, for the students of the College of the City of New York. Subsequent teaching suggested many changes and additions, until the manuscript was scarcely presentable. This manuscript has been copied for other schools ; and now, in order that those who have recently asked for it may receive it in better shape, this little volume is printed. I am indebted to Mr. Bashford Dean for the part relat- ing to injurious insects, which was written expressly for this book. I. S. New York, September, 1889. CONTENTS PAGE Introduction = , 7 Part First.—Wood. Structure of wood 13 Composition of wood 18 Branching of stems 19 Age of trees .20 Decay of trees 20 Season for cutting 21 Milling 31 Drying of wood 22 Warping 23 Properties of wood 24 Defects in wood 28 Measure and value of wood 29 Kinds of wood 30 Table of chief qualities of wood 38 Wood and iron 38 Wood-working trades 39 Parasitic plants . .41 Timber-borers 45 Preservation of wood 52 Part Second.—Exercises. -

Wood Identification and Chemistry' Covers the Physicalproperties and Structural Features of Hardwoods and Softwoods

11 DOCUMENT RESUME ED 031 555 VT 007 853 Woodworking Technology. San Diego State Coll., Calif. Dept. of Industrial Arts. Spons Agency-Office of Education (DHEA Washington, D.C. Pub Date Aug 68 Note-252p.; Materials developed at NDEA Inst. for Advanced Studyin Industrial Arts (San Diego, June 24 -Au9ust 2, 1968). EDRS Price MF -$1.00 He -$13.20 Descriptors-Curriculum Development, *Industrial Arts, Instructional Materials, Learning Activities, Lesson Plans, Lumber Industry, Resource Materials, *Resource Units, Summer Institutes, Teaching Codes, *Units of Study (Sublect Fields), *Woodworking Identifiers-*National Defense Education Act TitleXIInstitute, NDEA TitleXIInstitute, Woodworking Technology SIX teaching units which were developed by the 24 institute participantsare given. "Wood Identification and Chemistry' covers the physicalproperties and structural features of hardwoods and softwoods. "Seasoning" explainsair drying, kiln drying, and seven special lumber seasoning processes. "Researchon Laminates" describes the bending of solid wood and wood laminates, beam lamination, lamination adhesives,. andplasticlaminates."Particleboard:ATeachingUnitexplains particleboard manufacturing and the several classes of particleboard and theiruses. "Lumber Merchandising" outhnes lumber grades andsome wood byproducts. "A Teaching Unitin Physical Testing of Joints, Finishes, Adhesives, and Fasterners" describes tests of four common edge pints, finishes, wood adhesives, and wood screws Each of these units includes a bibhography, glossary, and student exercises (EM) M 55, ...k.",z<ONR; z _: , , . "'zr ss\ ss s:Ts s , s' !, , , , zs "" z' s: - 55 Ts 5. , -5, 5,5 . 5, :5,5, s s``s ss ' ,,, 4 ;.< ,s ssA 11111.116; \ ss s, : , \s, s's \ , , 's's \ sz z, ;.:4 1;y: SS lza'itVs."4,z ...':',\\Z'z.,'I,,\ "t"-...,,, `,. -

Motif Collection ‐ Panels

Motif Collection ‐ Panels • Exceptionally Easy Motif Collection Affordable To Install Imagine a room that emanates charm, The Motif Collection is affordable elegance. Each • Beautiful Ornate sophistication and grace – a room where each panel motif has been painstakingly designed to panel provides a classic statement about your capture an era, a style, a whim. Patterns décor, your personality, your home. • Accepts Paint Or Manufactured by skilled crafts people whose Stain Equally Well commitment to quality products is unsurpassed, our Motif Collection wall panels offer a multitude of stylish patterns etched into the finest quality • Convenient Panel materials allowing you to take a bland room and Sizes (32” x 48”) create a masterpiece brimming with ambiance. • Durable HDF Substrate Wall Panels: Customize your Room! Alexandria Moulding is very pleased to offer the opportunity to customize your panels to reflect your fantasies and whims. If you can imagine it we can create it. Think of it: Your own unique images Raised Colonial Brickwork etched into our panels! Grandchildren, your favourite car, couples, beverage and food themes, Options galore! etc. Just provide us with a photograph or reasonable facsimile of the image you desire and Voila! We will create it for you. The Motif Collection panels can be finished with Heritage Romanesque paints, stains, and clear coats varnishes. We have conducted numerous product tests to assure that our panels give you the best finishing characteristics available.* Use our panels in residential or commercial Colonial Custom applications. Beautify living rooms, offices, bedrooms, playrooms, and even ceilings! Quality & Durability The panels themselves are manufactured to exacting standards with extreme durability. -

Learning Guides 1009

Schuylkill Technology Center- South Campus 15 Maple Avenue Marlin, Pennsylvania 17951 (570) 544-4748 Mr. Kintzel Carpentry Instructor DUTY TITLE: 1000 Exterior Finish & 1100 Interior Finish COURSE TITLE: Carpentry COURSE CIP CODE: 46.0201 POS TASKS: 1009 Properly measure, layout and install an exterior set of stairs 1110 Properly measure, layout and install an interior set of stairs Mr. Kintzel – Carpentry Instructor STC South Campus 1 PUPOSE: Carpenters need to be able to layout stairs for any situation where they are needed. The layout of stairs do not change whether they are exterior or interior, however their level of finish does. NOCTI: Mr. Kintzel – Carpentry Instructor STC South Campus 2 Mr. Kintzel – Carpentry Instructor STC South Campus 3 PENNSYLVANIA CORE STANDARDS: Pennsylvania Core Standards for Writing for Technical Subjects Standard 3.6 Pennsylvania Core Standards for Reading for Technical Subjects Standard 3.5 Pennsylvania Core Standards for Mathematics Standard 2.1 CC.2.1.HS.F.2 Apply properties of rational and irrational numbers to solve real world or mathematical problems. CC.2.1.HS.F.4 Use units as a way to understand problems and to guide the solution of multi-step problems. CC.2.1.HS.F.5 Choose a level of accuracy appropriate to limitations on measurement when reporting quantities. CC.2.1.HS.F.6 Extend the knowledge of arithmetic operations and apply to complex numbers. Mr. Kintzel – Carpentry Instructor STC South Campus 4 REVISION: 8/2015 CERTIFICATION: NAHB HBI CERTIFICATION DIRECTIONS and PROCEDURES: 1. Read the complete module 2. Complete the following procedure steps 3. -

Don Schmid Vice President - Bob Brown Secretary - Barry Brandt Treasurer - Ron Cirincione

Volume 22 No.6 June, 2018 President - Don Schmid Vice President - Bob Brown Secretary - Barry Brandt Treasurer - Ron Cirincione Editor: Carl Hagen Email: [email protected] Website: www.tvwoodworkers.com Calendar of Events June 7 General Meeting Yacht Club 7:15 PM Spring Challenge June 23 Board Meeting Sloan’s Hardware 8:15 AM All Members Welcome July 8 Golf Outing Tanasi Golf Course 3:00 PM Shotgun Board Meeting Highlights – 6/02/2018 The TVWC Board met on June 2, 2018. Twenty- Club Kiln Bruce Barbre reported that painting of three members were present. The following items the outside of the kiln is complete, and $300 was were discussed and, as appropriate, acted upon. allocated for painting the interior when no wood drying is taking place. The oak and hickory in the Treasurers’ Report Current balances are: Club kiln is at 20% moisture. There are 14 oak and 5 Operations - $3197.60; Wood Operations - hickory logs in storage for cutting and drying but ($493.98); Kiln Amortization Fund - $4050.06; Toys have not been scheduled for processing. for Tots - $255. Total Ending Balance: $7008.68. Dick Hoffman updated the status of remote kiln Membership Report Chris Campbell reported monitoring. The POA has installed a new router current paid membership of 157. Thirteen dedicated for the kiln and the computer club has members have not paid their dues based on past donated a computer for communications. A email list and have been contacted. temperature sensor and control unit for temperature control for the computer has been identified with an Future Programs Ned Miller reported that the June approximate cost of $200. -

How to Cut and Install Moulding

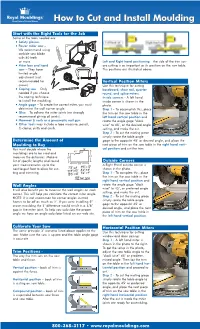

How to Cut and Install Moulding Start with the Right Tools for the Job Some of the tools needed are: • Safety glasses • Power miter saw – We recommend using carbide saw blade with 80 teeth or more. Left and Right hand positioning – the side of the trim you • Miter box and hand are cutting is as important as its position on the saw table. saw – They have The positions are illustrated above. limited angle adjustment (not recommended for Vertical Position Miters crown). Use this technique for cutting • Coping saw – Only baseboard, chair rail, quarter needed if you choose round, and splice miters. the coping technique Inside corners - A left hand to install the moulding. inside corner is shown in the • Angle gage – To create the correct miter, you must photo. determine the wall corner angle. Step 1 - To accomplish this, place • Glue – To adhere the miter joints (we strongly the trim on the saw table in the recommend gluing all joints). left hand vertical position and • Hammer & nails or a pneumatic nail gun. rotate the angle gage “clock • Other tools may include a tape measure, pencil, wise” to 45°, or the desired angle C-clamp, putty and caulk. setting, and make the cut. Step 2 - To cut the mating piece simply rotate the table angle Determine the Amount of gage to the opposite 45° or desired angle, and place the Moulding to Buy next piece of trim on the saw table in the right hand verti - You must decide where the cal position and cut the trim. mouldings are to be used and measure the distances. -

Frame Miter Joints

POWER-TOOL JOINERY Frame Miter Joints These elegant joints are difficult to cut and clamp. These jigs can help. he only frame joint that doesn’t leave a Tbit of end grain exposed is the miter joint. Given that it’s almost invisible when done right, it’s visually appealing, so you see it used for picture frames, for architectural trim, when assembling mouldings and oc- casionally in face or door frames. But it can be a problematic joint. Structurally, it’s a bit weak. Because it mates one tangentially cut end-grain surface (sometimes called “short grain”) with an- other, it’s weaker than a long-grain-to-long- grain joint. It’s stronger than end-grain to Photos by the author end-grain, but not much. Run some fasten- Spline and dovetail keys are basically just exposed splines.After the joint is glued up, just saw or rout a slot through its edge, then glue a key into the slot.Typically, the key is a contrasting wood so it can stand out. ers into a miter joint and you’re driving them into end grain, where they won’t hold well. Angling the fasteners helps, but not a lot. trimmers – but nothing seems to work. that is wider than 3". As the wood expands, Also, a miter is tough to cut accurately. On top of that, joint assembly is mad- the joint tends to open at the outside; when Haven’t we all struggled with a frame that dening because you have to find a way to pre- it contracts, the joint opens at the inside. -

Complete Instructions and Setup for Clincher Fence Machinetm and Smartfence

INCLUDES COLLECTION OF SIXTY, 16” long TEMPLATES and FULL SIZE PLANS FOR MAKING: • Box joints • Double-Double Box joints • Half-Blind Dovetails • Double Dovetails • Through & Double Through Dovetails • Jointech’s exclusive BoxtailsTM FULLY ILLUSTRATED WITH OVER • Plus 18 Scales for repetitive cutting 1 7 DETAILED ULL COLOR Cutting intervals range from /8” up to /8”. 200 F - DRAWINGS AND PHOTOS, PLUS NUMEROUS SHOP TIPS AND TECHNIQUES. Complete Instructions and Setup for MADE IN THE U.S.A. Manufactured by: TM ® Clincher Fence Machine and SmartFence . Jointech, Inc. SETUPS for CABINET MAKING OPERATIONS P.O. Box 790727 San Antonio, TX 78279 • Edge Jointing • Frames • Raised Panels Customer Svc : (210) 524-9104 Facsimile: (210) 377-1282 email:[email protected] Introduction CLINCHER FENCE MACHINE.....................................................................................2 Templates and scales Fence Machine Systems Warranty OPTIONAL ACCESSORIES.........................................................................................3 Setting Up SYSTEM SETUP and ASSEMBLY...............................................................................4 Mounting CLINCHER Mounting Fence Dust Collection Attachment Vertical Push Fixture assembly X-Y Stop Block operation Cutting Profile Inserts Cabinet Making EDGE JOINTING......... ................................................................................................6 Operations SHAPING OPERATIONS .............................................................................................7 -

Gluing Picture Frame Miters I Have Always Been Frustrated with the Difficulty in Gluing, and Especially Clamping 45 Degree Miter Joints

Gluing picture frame miters I have always been frustrated with the difficulty in gluing, and especially clamping 45 degree miter joints. On this page, I describe the best method of gluing such joints I have found yet. I don't consider this method to be very good, just the best that I have figured out so far. The perfect way to do corners is of course the way good cabinet makers make doors, which is to avoid miters altogether. This would require expensive router or shaper bits if any sort of profile is to be used, and even then doesn't look that good on picture frames. The main problem with gluing the miter joint is that after it has glue applied to it, it becomes very slippery. This is compounded by the fact that you can't apply the clamp to just press one joint together. Any pushing together of the joint will also usually cause it to slip a little bit. Even if you clamp it with two clamps from either side at once, you never get the forces quite balanced, and the darned thing slips. As if slipping sideways wasn't enough, the pieces also slip up and down, so getting a nicely aligned miter joints very frustrating. To eliminate part of the slippage, I like to slit the pieces of wood and insert a piece of wood, cut in such a way that the grain goes across, not along the piece of wood: 45 degree miter joint with joining piece This cut isn't totally easy, because it has to be very accurate. -

CMT Locking Miter Bit the Locking Miter Joint Is a Very Strong Joint

CMT Locking Miter Bit The locking miter joint is a very strong joint when made properly. This is the first of a number of articles making use of this great bit. C.M.T. UTENSILI S.p.A. Via della meccanica 61122 Pesaro - Fraz. chiusa di Ginestreto- Italy Tel. #39 0721 48571 Fax. #39 0721 481021 e-mail [email protected] www.cmtutensili.com The locking miter router bit is not new. I have seen it in ca- talogs for years. I have also read some articles on projects using it, but after seeing questions get asked frequently in the various woodworker forums, I decided it might be a good joint to learn first hand. I wanted to find out several things: 1) how easy was it to setup; 2) how strong was the joint; 3) was it attractive and finally 4) what router table, router and jigs would be necessary to use it properly and safely. At right, is the first joint I made...so either I was lucky or it is simple to use. It certainly looks good and seems to have very good gluing surfaces, so it should be pretty strong. Let me start at the beginning. The instructions say that one side is routed flat on the table and the other is held vertical against the fence. Here is the illustration from the CMT cata- log. Of course, that is if you are making a corner joint. The bit can also be used as a glue-up joint for mating parallel boards; that is a different story completely and will cover at the end. -

PWM Style Book Jan 2014.Pdf

Style Book Revised: January 2014 PW Style Book Revised: Jan 2014 Numbers, Measurements • #400-grit (adj) • 30 years adze (n): a primitive tool for surfacing lumber and Callouts • #400 grit (n) • #0000 steel wool • #1,000 grit stone • 1-pound cut, 2-pound cut etc. aftermarket (n): the market for parts, accessories and repairs • 40-tooth (adj) (for shellac) • thickness x width x length of a product; also, a secondary • On anything dimensional, • $2,800 (not $2800) • 1 horsepower; 1 hp (1-hp market for a product after the use numerals and birds’ feet, router); spell out ‘horsepower’ primary market; an aftermarket • 2" scale even if it’s an approximation on first reference, then can use fence for a table saw, for example • 32" x 48" ‘hp’ abbreviation (this departs from AP style) AIA (abbreviation): American • 4' x 7' 1/4"-20 (machine screw thread; • 4/4 lumber (reads as “four- Institute of Architects • 2x4; 2x4s (Name for quarter lumber”; refers to rough- 1/4" is diameter, 20 is threads per air-conditioner (n); construction-grade lumber, cut lumber measured by quarters inch) air-conditioning (A/C) (n); usually pine, generally used for or an inch; do not set as stacked • 70°F (no space; don’t spell out air-conditioned (adj) wall studs; is not really 2" by 4", fractions) on first ref.) air-dry (v); air-dried (adj): a but an estimate of the size used • mid-1800s • 3D (departure from AP) commonly; do not include inch method of seasoning lumber •30mm, 25 cm marks) which permits the sawn wood, • model 41293 which is usually protected from • 90° -

Setup Block for Lock Miter Bit

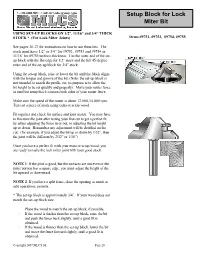

Setup Block for Lock Miter Bit USING SET -UP BLOCKS ON 1/2”, 11/16” and 3/4” THICK STOCK * (For Lock Miter Joints) Items #9751, #9753, #9754, #9755 See pages 26 -27 for instructions on how to use these bits. The stock must have 1/2” or 3/4” for #9751, #9753 and #9754 or 11/16” for #9755 uniform thickness. Use the miter end of the set- up block with the flat edge for 1/2” stock and the full 45-degree miter end of the set-up block for 3/4” stock. Using the set -up block, raise or lower the bit until the block aligns with the tongue and groove of the bit. (Note: the set-up block is not intended to match the profile cut; its purpose is to allow the bit height to be set quickly and properly). Move your router fence in until the setup block contacts both sides of your router fence. Make sure the speed of the router is about 12,000-14,000 rpm. Test cut a piece of stock using extra or scrap wood. Fit together and check for surface and joint match. You may have to fine tune the joint after testing your first cut to get a perfect fit, by either adjusting the fence in or out, or adjusting the bit height up or down. Remember any adjustment will be doubled on the cut. (for example, if you adjust the bit up or down by 1/32”, then the joint will be different by 2/32” or 1/16”) Once you have a perfect fit with your extra or scrap wood, you are ready to make the lock miter joint with your good stock.