Primary Education; Reading Comprehension

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literariness.Org-Mareike-Jenner-Auth

Crime Files Series General Editor: Clive Bloom Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fiction has never been more pop- ular. In novels, short stories, films, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, prim poisoners and overworked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground-breaking series offering scholars, students and discerning readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fiction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fiction, gangster movie, true-crime exposé, police procedural and post-colonial investigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehensive coverage and theoretical sophistication. Titles include: Maurizio Ascari A COUNTER-HISTORY OF CRIME FICTION Supernatural, Gothic, Sensational Pamela Bedore DIME NOVELS AND THE ROOTS OF AMERICAN DETECTIVE FICTION Hans Bertens and Theo D’haen CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN CRIME FICTION Anita Biressi CRIME, FEAR AND THE LAW IN TRUE CRIME STORIES Clare Clarke LATE VICTORIAN CRIME FICTION IN THE SHADOWS OF SHERLOCK Paul Cobley THE AMERICAN THRILLER Generic Innovation and Social Change in the 1970s Michael Cook NARRATIVES OF ENCLOSURE IN DETECTIVE FICTION The Locked Room Mystery Michael Cook DETECTIVE FICTION AND THE GHOST STORY The Haunted Text Barry Forshaw DEATH IN A COLD CLIMATE A Guide to Scandinavian Crime Fiction Barry Forshaw BRITISH CRIME FILM Subverting -

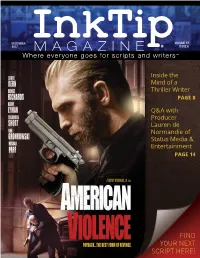

MAGAZINE ® ISSUE 6 Where Everyone Goes for Scripts and Writers™

DECEMBER VOLUME 17 2017 MAGAZINE ® ISSUE 6 Where everyone goes for scripts and writers™ Inside the Mind of a Thriller Writer PAGE 8 Q&A with Producer Lauren de Normandie of Status Media & Entertainment PAGE 14 FIND YOUR NEXT SCRIPT HERE! CONTENTS Contest/Festival Winners 4 Feature Scripts – FIND YOUR Grouped by Genre SCRIPTS FAST 5 ON INKTIP! Inside the Mind of a Thriller Writer 8 INKTIP OFFERS: Q&A with Producer Lauren • Listings of Scripts and Writers Updated Daily de Normandie of Status Media • Mandates Catered to Your Needs & Entertainment • Newsletters of the Latest Scripts and Writers 14 • Personalized Customer Service • Comprehensive Film Commissions Directory Scripts Represented by Agents/Managers 40 Teleplays 43 You will find what you need on InkTip Sign up at InkTip.com! Or call 818-951-8811. Note: For your protection, writers are required to sign a comprehensive release form before they place their scripts on our site. 3 WHAT PEOPLE SAY ABOUT INKTIP WRITERS “[InkTip] was the resource that connected “Without InkTip, I wouldn’t be a produced a director/producer with my screenplay screenwriter. I’d like to think I’d have – and quite quickly. I HAVE BEEN gotten there eventually, but INKTIP ABSOLUTELY DELIGHTED CERTAINLY MADE IT HAPPEN WITH THE SUPPORT AND FASTER … InkTip puts screenwriters into OPPORTUNITIES I’ve gotten through contact with working producers.” being associated with InkTip.” – ANN KIMBROUGH, GOOD KID/BAD KID – DENNIS BUSH, LOVE OR WHATEVER “InkTip gave me the access that I needed “There is nobody out there doing more to directors that I BELIEVE ARE for writers than InkTip – nobody. -

Do Not Leave This Assignment Until the Week Before School Starts

AP Statistics Summer Assignment To Start: Join the AP Statistics Google Classroom page with code: i5ynlu There you will find this summer assignment as well as the class syllabus Part 1: Reading & Vocabulary: Review - All the data analysis you may (or may not) have seen before. Use the Online Resource: http://www.stattrek.com/tutorials/ap-statistics-tutorial.aspx o On the left hand side of the page there is a list of topics. Read the topics listed below and complete the vocabulary definitions on the following pages of this packet. Under “The Basics” complete all subtopics: Variables, Population vs. Sample, Central Tendency, Variability & Position . Under “Charts and Graphs” complete all subtopics: Patterns in Data, Dot Plots, Histograms, Stem plots, Box plots, Scatter plots & Comparing Data Sets o Bookmark this site for later use: it’s a pretty solid study resource and is set up to follow the AP course! Part 2: Practice Problems Any charts or graphs can be done by hand or created using software (e.g., Excel / Google Sheets). Parts 1 and 2 ARE DUE THE VERY FIRST DAY OF CLASS IN SEPTEMBER. NO EXCUSES. IT WILL BE CHECKED FOR COMPLETENESS. THIS ASSIGNMENT ESTABLISHES MUCH OF THE VOCABULARY I AND YOUR BOOK WILL BE USING TO DESCRIBE MORE ADVANCED STATISTICS. IT IS CRITICAL YOU TAKE IT SERIOUSLY. I WILL ASSUME ON DAY ONE YOU ARE AT LEAST FAMILIAR WITH THESE VOCABULARY TERMS. Part 3: Procure a graphing calculator This course and the AP exam requires a graphing calculator. I recommend the TI-83 or TI-84 models and will be teaching the course assuming you have one. -

Numb3rs Episode Guide Episodes 001–118

Numb3rs Episode Guide Episodes 001–118 Last episode aired Friday March 12, 2010 www.cbs.com c c 2010 www.tv.com c 2010 www.cbs.com c 2010 www.redhawke.org c 2010 vitemo.com The summaries and recaps of all the Numb3rs episodes were downloaded from http://www.tv.com and http://www. cbs.com and http://www.redhawke.org and http://vitemo.com and processed through a perl program to transform them in a LATEX file, for pretty printing. So, do not blame me for errors in the text ^¨ This booklet was LATEXed on June 28, 2017 by footstep11 with create_eps_guide v0.59 Contents Season 1 1 1 Pilot ...............................................3 2 Uncertainty Principle . .5 3 Vector ..............................................7 4 Structural Corruption . .9 5 Prime Suspect . 11 6 Sabotage . 13 7 Counterfeit Reality . 15 8 Identity Crisis . 17 9 Sniper Zero . 19 10 Dirty Bomb . 21 11 Sacrifice . 23 12 Noisy Edge . 25 13 Man Hunt . 27 Season 2 29 1 Judgment Call . 31 2 Bettor or Worse . 33 3 Obsession . 37 4 Calculated Risk . 39 5 Assassin . 41 6 Soft Target . 43 7 Convergence . 45 8 In Plain Sight . 47 9 Toxin............................................... 49 10 Bones of Contention . 51 11 Scorched . 53 12 TheOG ............................................. 55 13 Double Down . 57 14 Harvest . 59 15 The Running Man . 61 16 Protest . 63 17 Mind Games . 65 18 All’s Fair . 67 19 Dark Matter . 69 20 Guns and Roses . 71 21 Rampage . 73 22 Backscatter . 75 23 Undercurrents . 77 24 Hot Shot . 81 Numb3rs Episode Guide Season 3 83 1 Spree ............................................. -

Death Penalty Hits Historic Lows Despite Federal Execution Spree Pandemic, Racial Justice Movement Fuel Continuing Death Penalty Decline

The Death Penalty in 2020: Year End Report Death Penalty Hits Historic Lows Despite Federal Execution Spree Pandemic, Racial Justice Movement Fuel Continuing Death Penalty Decline DEATH SENTENCES BY YEAR 3 Key Findings Peak: 315 in 1996 3 • Colorado becomes nd 22 state to abolish 2 death penalty 2 • Reform prosecutors gain footholds in 1 formerly heavy-use 1 death penalty counties 297 50 • Fewest new death 18 in 2020 sentences in modern 0 1973 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020 era; state executions lowest in 37 years EXECUTIONS BY YEAR • Federal government 1 resumes executions Peak: 98 in 1999 with outlier practices, for first time ever 80 conducts more executions than all 60 states combined • COVID-19 pandemic 40 halts many 81 executions and court 2 proceedings; federal 17 in 2020 executions spark 0 1977 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020 outbreaks The Death Penalty in 2020: Year End Report Introduction Death Row by State State 2020† 2019† 2020 was abnormal in almost every way, and that was clearly the case when it came to capital punishment in the United States. The California 724 729 interplay of four forces shaped the U.S. death penalty landscape in Florida 346 348 2020: the nation’s long - term trend away from capital punishment; the Texas 214 224 worst global pandemic in more than a century; nationwide protests Alabama 172 177 for racial justice; and the historically aberrant conduct of the federal North Carolina 145 144 administration. At the end of the year, more states had abolished the Pennsylvania 142 154 death penalty or gone ten years without an execution, more counties Ohio 141 140 had elected reform prosecutors who pledged never to seek the death Arizona 119 122 penalty or to use it more sparingly; fewer new death sentences were Nevada 71 74 imposed than in any prior year since the Supreme Court struck down Louisiana 69 69 U.S. -

302Goldenrodrev7.26 Script

Goldenrod REV: 7/26/06 Green REV: 7/26/06 Yellow REV: 7/24/06 Pink REV: 7/20/06 Blue REV: 7/18/06 “Two Daughters” #302/Ep.39 Written by Ken Sanzel Directed by Alex Zakrzewski SCOTT FREE in association with CBS PARAMOUNT NETWORK TELEVISION, a division of CBS Studios. Copyright 2006 CBS Paramount Network Television. All Rights Reserved. This script is the property of CBS Paramount Network Television and may not be copied or distributed without the express written permission of CBS Paramount Network Television. This copy of the script remains the property of CBS Paramount Network Television. It may not be sold or transferred and it must be returned to CBS Paramount Network Television promptly upon demand. THE WRITING CREDITS MAY OR MAY NOT BE FINAL AND SHOULD NOT BE USED FOR PUBLICITY OR ADVERTISING PURPOSES WITHOUT FIRST CHECKING WITH TELEVISION LEGAL DEPARTMENT. Goldenrod REV July 26th, 2006 #302/Ep.39 “Two Daughters” GOLDENROD Revisions 7/26/2006 SCRIPT REVISION HISTORY COLOR DATE PAGES WHITE 7/14/06 (1-60) BLUE Rev 7/18/06 (1,2,3, 7,8,12,13,27,28,30,32,33 36,39,42,42A,48,49,50,53 54,55,55A) Pink Rev 7/20/06 (15,16,41,42, 42A,43,49,52,56,56A) Yellow Rev 7/24/06 (1,15,17,17A,22,24,25, 26,27,34,34A,36,44,49,52 52A,53,55,55A,57,58) Green Rev 7/26/06 (2,5,8,10,15,19,21,22, 23,24,27,28,29,31,32,32A 33,34,34A,36,38,42,42a, 44,45,49,51,54,55) Goldenrod Rev 7/26/06 (5,6,31) #302/Ep.39 “Two Daughters” GOLDENROD Revisions 7/26/2006 SET LIST INTERIORS EXTERIOR FBI PROCESSING AREA STREET BULLPEN WAR ROOM TWILIGHT MOTEL* INTERVIEW ROOM MOTEL ROOM INTERROGATION ROOM OBSERVATION ROOM DAVID & COLBY’S CAR HALLWAY TECH ROOM DON’S CAR COFFEE ROOM FBI BRIDGE MOTEL ROOM BATHROOM SUBURBAN HOUSE HOUSE CRYSTAL’S CAR GARAGE ROADBLOCK DAVID & COLBY’S CAR CALSCI CAMPUS DON’S CAR ABANDONED HOUSE HOSPITAL ROOM CORRIDOR LOBBY EPPES HOUSE LIVING ROOM CHARLIE’S OFFICE ADAM BENTON’S HOME OFFICE CRYSTAL’S CAR "TWO DAUGHTERS" TEASER BLACK BOX OPENING: 15.. -

Powell Woman Placed on Probation for Burglary Spree

THURSDAY, MARCH 28, 2019 109TH YEAR/ISSUE 25 Powell woman placed on NEW CITY ADMINISTRATOR probation for burglary spree BY CJ BAKER program last year persuaded are violations of the terms and Overfield instead suspended Tribune Editor District Court Judge Bobbi conditions of this probation, eight to 10 years of prison time, Overfield to give the … the state most which the judge could impose if Powell woman has been defendant an oppor- likely won’t hesitate Lamb-Harlan makes a misstep sentenced to three years tunity to prove that to bring you back on probation. Aof supervised probation she’s changed. before this court — During the two years that for committing a string of bur- “I can pretty much and most likely, this her cases were pending in Park glaries in 2017, while on proba- guarantee you with court won’t hesitate County’s court system, Lamb- tion for a meth-related offense. this sentence that to impose a sentence Harlan served roughly a year Prosecutors and Valorie you’re going to be accordingly.” and two months in jail. Lamb-Harlan’s probation under some pret- Deputy Park She tearfully apologized for agent had recommended that ty strict scrutiny County Prosecuting her actions at Friday’s hearing. the 45-year-old be sent to for the next three Attorney Leda Po- “I know I have been, like, out prison. But Lamb-Harlan’s years,” Overfield jman argued for of control because of drugs and apparent turnaround after she warned Lamb-Har- VALORIE a nine- to 10-year completed a drug treatment lan. -

Five Possible Advantages of Watching TV Series Over Movies For

Five Possible Advantages of Watching TV Series over Movies 1 for Autonomous Learners of English KOBAYASHI Toshihiko (Otaru University of Commerce) Abstract This research paper is intended to demonstrate the possible superiority of watching TV series over movies for autonomous EFL learners for an extended period of time by identifying and discussing the following five potential advantages: 1) Learners save time and expend less energy; 2) Development of a wider repertoire of learners’ vocabulary; 3) A further deepening or supplementing of learners’ subject matter knowledge; 4) A greater improvement in learners’ listening comprehension; and 5) Motivating learners for a longer period of time. To maximize these advantages, an autonomous learning model through TV series is proposed with the following five steps: 1. Viewing & Note-Taking (Listening); 2. Discussion (Speaking); 3. Script-Reading & Vocabulary Check (Reading); 4. Writing Comments (Writing); and 5. Making Vocabulary Lists (Recording). Finally, some limits on the practice of this learning model and what is expected from EFL teachers to promote learner autonomy will be discussed. Key words: TV series / movies / advantages / autonomous / learning 1. Introduction One possible way to guarantee voluntary exposure to the target language outside the classroom for adult EFL learners is to relate English learning to their curiosity and major field of studies and/or professional needs by providing them with academic and professional benefits as well as linguistic ones. Movies and TV series can serve as some of the most powerful and sustainable materials to offer EFL learners authentic English input for an extended period of time. They are especially suitable for motivating learners in autonomous settings once they are set free from a strict pedagogical framework or school requirements (Kobayashi, 2011; Tanaka, 2013). -

The Numbers Behind Numb3rs: Solving Crime with Mathematics Free

FREE THE NUMBERS BEHIND NUMB3RS: SOLVING CRIME WITH MATHEMATICS PDF Professor Keith Devlin,Gary Lorden | 243 pages | 27 Apr 2009 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780452288577 | English | New York, NY, India Numbers (TV series) - Wikipedia The show focuses equally on the relationships among Don Eppes, his brother Charlie Eppes, and their father, Alan Eppes Judd Hirschand on the brothers' efforts to fight crime, usually in Los Angeles. The insights provided by Charlie's mathematics were The Numbers Behind Numb3rs: Solving Crime with Mathematics in some way crucial to solving the crime. Temporary characters on the show were often named after famous mathematicians. Opening: Voice-over by David Krumholtz We all use math The Numbers Behind Numb3rs: Solving Crime with Mathematics day. To predict weather…to tell time…to handle money. Math is more than formulas and equations. It's logic; it's rationality. It's using your The Numbers Behind Numb3rs: Solving Crime with Mathematics to solve the biggest mysteries we know. Don and Charlie's father, Alan Eppes, provides emotional support for the pair, while Professor Larry Fleinhardt and doctoral student Amita Ramanujan provide mathematical support and insights to Charlie. Season one was a half-season, producing only 13 episodes. Charlie is challenged on one of his long-standing pieces of mathematical work and also starts work on a new theory, cognitive emergence theory. Larry sells his home and assumes a nomadic lifestyle, while he becomes romantically involved with Megan. Amita receives an offer for an assistant professor position at Harvard Universitybut is plagued by doubt as her relationship with Charlie is challenged and her career is in upheaval. -

Volume 50 • Number 4 • July 2009

VOLUME 50 • NUMBER 2009 4 • JULY Feedback [ [FEEDBACK ARTICLE ] ] July 2009 (Vol. 50, No. 4) Feedback is an electronic journal scheduled for posting six times a year at www.beaweb.org by the Broadcast Education Association. As an electronic journal, Feedback publishes (1) articles or essays— especially those of pedagogical value—on any aspect of electronic media: (2) responsive essays—especially industry analysis and those reacting to issues and concerns raised by previous Feedback articles and essays; (3) scholarly papers: (4) reviews of books, video, audio, film and web resources and other instructional materials; and (5) official announcements of the BEA and news from BEA Districts and Interest Divisions. Feedback is editor-reviewed journal. All communication regarding business, membership questions, information about past issues of Feedback and changes of address should be sent to the Executive Director, 1771 N. Street NW, Washington D.C. 20036. SUBMISSION GUIDELINES 1. Submit an electronic version of the complete manuscript with references and charts in Microsoft Word along with graphs, audio/video and other graphic attachments to the editor. Retain a hard copy for refer- ence. 2. Please double-space the manuscript. Use the 5th edition of the American Psychological Association (APA) style manual. 3. Articles are limited to 3,000 words or less, and essays to 1,500 words or less. 4. All authors must provide the following information: name, employer, professional rank and/or title, complete mailing address, telephone and fax numbers, email address, and whether the writing has been presented at a prior venue. 5. If editorial suggestions are made and the author(s) agree to the changes, such changes should be submitted by email as a Microsoft Word document to the editor. -

Planting and Growing Chestnut Trees

Planting and growing chestnut trees The Pennsylvania Chapter of the American Chestnut Foundation Planting and growing chestnut trees is a rewarding drained and somewhat acidic soil (pH 4.5-6.5) on challenge. As with growing anything, there are gently sloping fertile land is best. Avoid heavy clay soils. Review your property’s location on some tips and tricks to growing chestnut trees. The county soil maps from the Natural Resources goal of the Pennsylvania Chapter of the American Conservation Services (NRCS). Many of these Chestnut Foundation (PA-TACF) is to restore the are available on-line (http:// American chestnut (Castanea dentata) to the forests websoilsurvey.nrcs.usda.gov/app/), but you may also find them in you local library. of the mid-Atlantic. To do this, we must plant a lot 2) Avoid planting in swales. of trees! To date, we have planted over 22,000 trees 3) Exposure. Full sun is best for growth, vigor and as part of our mission. If you plan to join our efforts, seed production. A sheltered north-facing slope please take a few minutes to review the following protected from drying winds and low sun of win- ter may be better for cold windy sites. Planting information so that you might get the most out of on a slope may also help alleviate some drainage your chestnut planting. We hope that by following issues. the recommendations contained within, that you will 4) Site preparation will depend on the condition of realize the growth potential necessary for timely in- the site. If the site is uncultivated, trees and brush should be removed, the field mowed, and re- oculation and nut production. -

Methamphetamines an Epidemic Lyshorn 1

Methamphetamines an Epidemic Lyshorn 1 Methamphetamines: An Epidemic By Nicole A. Lyshorn Advised by Dr. Barbara Mori ANT 461, 462 Senior Project Social Sciences Department College of Liberal Arts CALIFORNIA POLYTECHNIC STATE UNIVERSITY Winter 2006 Methamphetamines an Epidemic Lyshorn 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Outline……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………Pg. 3 I. Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………Pg. 4 II. The History of Methamphetamine..………………………………………………………………….………………………….Pg. 5 III. Case Studies—Real Life Accounts of Meth Additions…………………………………………………………………..Pg. 14 IV. Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………………………..............................Pg. 22 V. Reference List……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….Pg.25 Methamphetamines an Epidemic Lyshorn 3 OUTLINE A. Introduction B. The History of Methamphetamine a. How Is Crystal Meth Made b. Who Uses Crystal Meth c. Ethnicity, Subpopulations and Gender d. How Is Crystal Meth Used e. How Crystal Meth Affects the Body, Mind, Relationships and Environment i. The Body ii. The Mind iii. Relationships iv. Environment f. Treatment Options and Outcomes C. Case Studies- Real Life Accounts of Meth Addiction a. Travis C. b. Steven D. c. Freddie D. D. Conclusion Methamphetamines an Epidemic Lyshorn 4 Introduction Imagine you are 17 years old and locked up, again. You aren’t a murderer or rapist, you are an addict, and it’s all you have ever known. You are shaking uncontrollably, sweating profusely, seeing and hearing things that aren’t really there, vomiting, and screaming in agony. You are coming down off of one of the most addictive and destructive drugs in the world today, Meth. On the street it’s called ice, glass, crank, chalk, or crystal, to you it’s the substance that has destroyed every relationship you’ve ever had, its destroyed your family, kept you from getting your high school diploma and from having any kind of social group of friends other than the other meth heads you know who seek what you seek; the ultimate high.