Schools and the Class Divide: an Examination of Children's Self

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inward 347 Documents 348 Homily

BIBLIOGRAPHY LIST OF CONTENTS Page BOOKS AND ARTICLES 311 CONCERT 347 CORRESPONDENCE - INWARD 347 DOCUMENTS 348 HOMILY 351 INTERVIEWS 351 LECTURES 354 MEETINGS 354 BOOKS AND ARTICLES A Pilgrim's Testament: The Memoirs of Ignatius of Loyola (1983) Divarkar, P. (Trans.) Rome, Gregorian University. Abbott, W. (Ed.) (1966) The Documents of Vatican II, London, Chapman. Abbs, P. (1974) Autobiography in Education, London, Heinemann. Abercrombie, N., Hill, S. and Turner, B., (1988) Dictionary of Sociology, London, Penguin. Accardi, R. (1989) 'Corporate Prophetability: The Prophetic Role of the Governance Liaison', Review for Religious, 48, 6, November - December, pp.915-921. Adelman, C. (Ed.) (1981) Uttering, Muttering Collecting, Using and Reporting Talk for Social and Educational Research, London, Grant McIntyre. Adelman, C., Jenkins, D., and Kemmis, S. (1980) 'Rethinking Case Study: Notes from the Second Cambridge Conference' in Simons, H (Ed.) (1980) Towards a Science of the Singular, University of East Anglia, Centre for Applied Research in Education, Occasional Publication No. 10. Adie, M. (1990a) 'Restoring responsibility', Education, 176, 24, 14th December. Adie, M. (1990b) 'Basic or marginal?', Education, 176, 25/26, 21st/28th December. Albrow, M. (1970) Bureaucracy Key Concepts in Political Science, London, Macmillan. Albrow, M. (1990) Max Weber's Construction of Social Theory, London, Macmillan. Aldrich, R. (1982) An Introduction to the History of Education, London, Hodder and Stoughton. Alexander, D. (1991) 'Curriculum turmoil in liberal democracies', Journal of Curriculum Studies, 23, 1, pp.71-78. Allan, R. and Hill, R. (1991) 'Political Illiteracy and Australian Teacher Education Programmes', Social Science Teacher, 20, 3, Summer, pp.87- 89. Allen, R. -

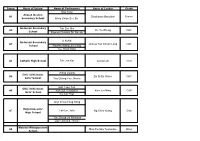

Group Name of School Name of Leader Grade A4 Catholic High

Group Name of School Name of Participants Name of Leader Grade Koe Yunji Ahmad Ibrahim A1 Divakaran Manushri Bronze Secondary School Alicia Chian See En Anderson Secondary Toh Sze Min A2 Xie Yu Zheng COC School Kamma Chavala Sri Nikesh Li XuKai Anderson Secondary A3 Joshua Tan Choon Long COC School Rodney Wang Jun Long Lee Hong DIng A4 Catholic High School Tan Jen Kai Lucas Loh Gold Wong Liyang CHIJ St Nicholas A5 Zai Si En Grace COC Girls' School Yeo Cheng Yee, Nicole Koh Tzee Yen CHIJ St Nicholas A6 Koh Ziyi, Geraldine Koh Jun Ning COP Girls' School Kyi Cin Thet Jeryl Chwa Fong Rong Holy Innocents' A7 Toh Lin, Jolin Ng Chee Kiang Gold High School Tan Zheng Jie Nicholas Dave Adelaide Nicole Mahidol Wittayanusorn A8 Miss Pemika Teeranate Silver School Mahidol Wittayanusorn Miss Patchariya A9 Gold School Chawalitjinda Tammy Lim Pasir Ris Crest A10 Sarah Ann Goh Wen Yu Chiranjeeb Satpathy COP Secondary School Amarambedu Ramesh Princess Chulabhorn’s A11 Science High School Natnicha Pichai COC Chiang Rai, Thailand School of Science and Nadrah Nabiha Binte Mohd A12 Technology, Singapore Fairus Goh Ann Kyee Bronze Zowie Ong Zu Yi School of Science and A13 Chong Zheng Xuan Tan Sze Ian Silver Technology, Singapore St. Margaret's Anya Chia Emmanuelle Xie-En A14 Secondary COP Tan Hui Xin Julia Sudharman School Foon Yi Teng Travis Eswaran Yio Chu Kang Shreeyaa Subramanian Soukkaseum A15 COC Secondary School Wongreantong Madtika Moungkhoun Jewell Png Zi Ting Group Name of School: Name of Participants Name of Leader Grade Jessica Long Mei Yun Ahmad -

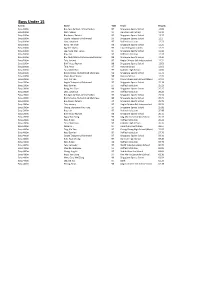

Boys Under 15

Boys Under 15 Events Name YOB Team Results Boys 100m Bin Agos Sahbali, Amirul Sofian 97 Singapore Sports School 12.09 Boys 100m Moh, Shaun 97 Dunman High School 12.11 Boys 100m Bin Anuar, Zuhairi 97 Singapore Sports School 12.17 Boys 100m Sugita Tadayoshi, Richmond 97 Singapore Sports School 12.2 Boys 100m Lew, Jonathon 97 Raffles Institution 12.23 Boys 100m Kang, Yee Cher 98 Singapore Sports School 12.25 Boys 100m Ng, Kee Hsien 97 Hwa Chong Institution 12.25 Boys 100m Lee, Song Wei, Lucas 97 Singapore Sports School 12.36 Boys 100m Poy, Ian 97 Raffles Institution 12.37 Boys 100m Bin Abdul Wahid, Muhammad Syazani 98 Singapore Sports School 12.44 Boys 100m Toh, Jeremy 97 Anglo Chinese Sch Independant 12.51 Boys 100m Bin Fairuz, Rayhan 98 Singapore Sports School 12.63 Boys 100m Thia, Aven 97 Victoria School 12.63 Boys 100m Tan, Chin Kean 97 Catholic High School 12.66 Boys 100m Bin Norzaha, Muhammad Shahrieza 98 Singapore Sports School 12.72 Boys 100m Chen, Ryan Shane 98 Victoria School 12.73 Boys 200m Ong, Xin Yao 97 Chung Cheng High School (Main) 24.91 Boys 200m Sugita Tadayoshi, Richmond 97 Singapore Sports School 25.18 Boys 200m Kee, Damien 97 Raffles Institution 25.23 Boys 200m Kang, Yee Cher 98 Singapore Sports School 25.25 Boys 200m Lew, Jonathon 97 Raffles Institution 25.26 Boys 200m Bin Agos Sahbali, Amirul Sofian 97 Singapore Sports School 25.50 Boys 200m Bin Norzaha, Muhammad Shahrieza 98 Singapore Sports School 25.71 Boys 200m Bin Anuar, Zuhairi 97 Singapore Sports School 25.72 Boys 200m Toh, Jeremy 97 Anglo Chinese Sch Independant -

S/N MOE Schools 1 Admiralty Primary School 2 Admiralty Secondary School 3 Ahmad Ibrahim Primary School 4 Ahmad Ibrahim Second

S/N MOE Schools 1 Admiralty Primary School 2 Admiralty Secondary School 3 Ahmad Ibrahim Primary School 4 Ahmad Ibrahim Secondary School 1 Ai Tong School 2 Alexandra Primary School 3 Anchor Green Primary School 4 Anderson Primary School 5 Anderson Secondary School 6 Anderson Serangoon JC 7 Ang Mo Kio Primary School 8 Ang Mo Kio Secondary School 9 Anglican High (Secondary) 10 Anglo-Chinese Junior College 11 Anglo-Chinese Primary School (Barker Rd) 16 Anglo-Chinese School (Junior) 17 Anglo-Chinese Secondary School (Barker Rd) 18 Angsana Primary School 19 Assumption English School 20 Assumption Pathway School 21 Bartley Secondary School 22 Beacon Primary School 23 Beatty Secondary School 24 Bedok Green Primary School 25 Bedok Green Secondary School 26 Bedok South Secondary School 27 Bedok View Secondary School 28 Bendemeer Primary School 29 Bendemeer Secondary School 30 Blangah Rise Primary School 31 Boon Lay Garden Primary School 32 Boon Lay Secondary School 33 Bowen Secondary School 34 Broadrick Secondary School 35 Bukit Batok Secondary School 36 Bukit Merah Secondary School 37 Bukit Panjang Govt High School 38 Bukit Panjang Primary School 39 Bukit Timah Primary School 40 Bukit View Primary School 41 Bukit View Secondary School 42 Canberra Primary School 43 Canberra Secondary School 44 Canossa Catholic Primary School 45 Cantonment Primary School 46 Casuarina Primary School 47 Catholic High School (Primary) 48 Catholic High School (Secondary) 49 Catholic Junior College 50 Cedar Girls Secondary School 51 Cedar Primary School 52 Changi Coast -

The Grand Final of the Singapore Secondary

Singapore Secondary Schools Debating Championships Grand Finalist Schools Division I Division II Division III Year Champions Runners-Up Champions Runners-Up Champions Runners-Up Anglo-Chinese National Junior Chung Cheng Bukit Batok Catholic High Raffles 2014 School College High School Secondary School Institution (Barker Road) (Junior High) (Yishun) School Anglo-Chinese National Junior Serangoon Raffles Temasek Tanjong Katong 2013 School College Secondary Institution Academy Girls’ School (Independent) (Junior High) School Jurong Orchid Park Raffles Hwa Chong N.U.S. High River Valley 2012 Secondary Secondary Institution Institution School High School School School National C.H.I.J. Singapore Ngee Ann Westwood Raffles 2011 Junior College St. Joseph’s American Secondary Secondary Institution (Junior High) Convent School School School St. Anthony’s Anglo-Chinese C.H.I.J. Kent Ridge Hwa Chong Raffles Canossian 2010 School St. Joseph’s Secondary Institution Institution Secondary (Barker Road) Convent School School Global Indian Paya Lebar C.H.I.J. Jurong Raffles Hwa Chong International 2009 Methodist Girls’ St. Joseph’s Secondary Institution Institution School School Convent School (Queenstown) Fairfield S.J.I. Yishun Town Raffles Nanyang Girls’ Methodist Nan Chiau 2008 International Secondary Institution High School Secondary High School School School School Singapore Xinmin Anglo-Chinese Bowen Catholic High Nan Hua 2007 Chinese Girls’ Secondary School Secondary School High School School School (Barker Road) School Anglo-Chinese Queenstown Bukit View Methodist Girls’ Temasek Victoria Junior 2006 School College Secondary Secondary School Academy (Independent) (Integrated Programme) School School Anglo-Chinese National Junior St. Margaret’s Tanjong Katong Raffles Dunman High 2005 School College Secondary Secondary Institution School (Independent) (Junior High) School School Anglo-Chinese United World C.H.I.J. -

GAZETTE Parliamentary Elections

THURSDAY, JULY 9, 2020 1 First published in the Government Gazette, Electronic Edition, on 7 July 2020 at 6.40 pm. No. 1382 –– PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS ACT (CHAPTER 218) NOTICE UNDER SECTION 48A(3) Notice is given under section 48A(3) of the Parliamentary Elections Act that the Returning Officer has –– (a) under section 48A(1)(a) of the Act, directed that the votes cast at each polling station in Singapore set out in the first column of the Schedule for an electoral division be counted at the counting place specified in the second column of the Schedule for that polling station; (b) under section 48A(1)(b) of the Act, directed that the total number of votes given to each candidate or group of candidates at the poll in an electoral division be ascertained at the principal counting place specified for that electoral division in the third column of the Schedule; and (c) under section 48A(2) of the Act, directed that the votes cast at all overseas polling stations be counted at ELD Training Centre, 508 Victoria Street, Singapore 198372. 2. Counting of votes at each counting place specified in the second column of the Schedule will commence after the poll closes on 10 July 2020 and the Assistant Returning Officer in charge of the counting place receives at that counting place all the ballot boxes containing the votes cast at the polling station or stations in Singapore specified in the first column of the Schedule for that counting place. 3. The total number of votes given to each candidate or group of candidates at the poll in an electoral division will be ascertained at the principal counting place specified in the third column of the Schedule for that electoral division upon receipt of the results of the counting of votes cast in Singapore for that electoral division at all the counting places specified for that electoral division in the second column of the Schedule and in the notice under section 6(2)(g) of the Parliamentary Elections (COVID-19 Special Arrangements) Act 2020 (Act 21 of 2020) published on 7 July 2020 (G.N. -

PRESS RELEASE Ministry of Education

PRESS RELEASE Ministry of Education 9 February 2007 RESULTS OF THE 2006 SINGAPORE-CAMBRIDGE GENERAL CERTIFICATE OF EDUCATION (ORDINARY LEVEL) EXAMINATION 1 The Singapore-Cambridge General Certificate of Education Ordinary Level Examination is conducted jointly by the University of Cambridge Local Examinations Syndicate, the Singapore Examinations and Assessment Board and the Ministry of Education. 2 There were 38,593 school candidates in the 2006 examination. Of these, 38,550 or 99.9% have been awarded certificates. In the 2005 examination, there were 37,400 school candidates or 99.9% who were awarded certificates. An information sheet on schools and students with good performance is at ANNEX A. 3 The results of the 2006 and 2005 examinations for school candidates are as follows: 1 or more GCE 3 or more GCE 5 or more GCE Year No. Sat ‘O’ Level Passes ‘O’ Level Passes ‘O’ Level Passes No. % No. % No. % 2006 38,593 38,550 99.9 36,710 95.1 31,490 81.6 2005 37,427 37,400 99.9 35,646 95.2 30,212 80.7 4 A total of 2,746 private candidates sat for the 2006 examination. Of these, 2,387 or 86.9% have been awarded certificates. 5 School candidates have been issued their results by their respective schools on 9 February 2007. Private candidates will be informed of their results by post. Private candidates may also access their results through the Singapore Examinations and Assessment Board internet website at ‘http://www.seab.gov.sg’ from 2.30 p.m. on 9 February 2007. -

Government & Government-Aided Schools

GOVERNMENT & GOVERNMENT-AIDED SCHOOLS S/N. SCHOOLS 1 ADMIRALTY SECONDARY SCHOOL 2 AHMAD IBRAHIM SECONDARY SCHOOL 3 ANDERSON SECONDARY SCHOOL 4 ANG MO KIO SECONDARY SCHOOL 5 ANGLICAN HIGH SCHOOL 6 ANGLO-CHINESE SCHOOL (BARKER ROAD) 7 ASSUMPTION ENGLISH SCHOOL 8 BARTLEY SECONDARY SCHOOL 9 BEATTY SECONDARY SCHOOL 10 BEDOK GREEN SECONDARY SCHOOL 11 BEDOK SOUTH SECONDARY SCHOOL 12 BEDOK VIEW SECONDARY SCHOOL 13 BENDEMEER SECONDARY SCHOOL 14 BOON LAY SECONDARY SCHOOL 15 BOWEN SECONDARY SCHOOL 16 BROADRICK SECONDARY SCHOOL 17 BUKIT BATOK SECONDARY SCHOOL 18 BUKIT MERAH SECONDARY SCHOOL 19 BUKIT PANJANG GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL 20 BUKIT VIEW SECONDARY SCHOOL 21 CANBERRA SECONDARY SCHOOL 22 CATHOLIC HIGH SCHOOL 23 CEDAR GIRLS' SECONDARY SCHOOL 24 CHANGKAT CHANGI SECONDARY SCHOOL 25 CHIJ KATONG CONVENT 26 CHIJ SECONDARY (TOA PAYOH) 27 CHIJ ST. JOSEPH'S CONVENT 28 CHIJ ST. NICHOLAS GIRLS' SCHOOL 29 CHIJ ST. THERESA'S CONVENT 30 CHRIST CHURCH SECONDARY SCHOOL 31 CHUA CHU KANG SECONDARY SCHOOL 32 CHUNG CHENG HIGH SCHOOL (MAIN) 33 CHUNG CHENG HIGH SCHOOL (YISHUN) 34 CLEMENTI TOWN SECONDARY SCHOOL 35 COMMONWEALTH SECONDARY SCHOOL 36 COMPASSVALE SECONDARY SCHOOL 37 CRESCENT GIRLS' SCHOOL 38 DAMAI SECONDARY SCHOOL 39 DEYI SECONDARY SCHOOL 40 DUNEARN SECONDARY SCHOOL 41 DUNMAN HIGH SCHOOL 42 DUNMAN SECONDARY SCHOOL 43 EAST SPRING SECONDARY SCHOOL 44 EDGEFIELD SECONDARY SCHOOL 45 EVERGREEN SECONDARY SCHOOL 46 FAIRFIELD METHODIST SCHOOL (SECONDARY) 47 FAJAR SECONDARY SCHOOL 48 FUCHUN SECONDARY SCHOOL 49 FUHUA SECONDARY SCHOOL 50 GAN ENG SENG SCHOOL 51 GEYLANG METHODIST -

Annual Report 2020

NATIONAL YOUTH ACHIEVEMENT AWARD ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Today's Youth, Tomorrow's Leaders CONTENT Page Executive Summary 1 Mission 2 Policies 2 Policy Relating to Management and Conflict of Interest 4 Future Plans 4 Review of The Year 2020 5 Review of Financial Status 6 Governance Evaluation Checklist 6 Appendix 1: Organisation Structure 8 Appendix 2: NYAA Advisory Board 9 Appendix 3: NYAA National Council 12 Appendix 4: NYAA Board of Trustees 15 Appendix 5: NYAA Operating Partners 16 Appendix 6: NYAA New Participants and Awards Awarded 21 Appendix 7: Summary of Financial Performance for 2020 22 Appendix 8: Online Financial Summary for 2018 to 2020 23 Appendix 9: Donations for 2020 25 Appendix 10: Valuation Report on Investment Property 26 Appendix 11: National Council Meetings Attendance 27 Appendix 12: Chairman’s Report for 2020 29 Appendix 13: Executive Director’s Report for 2020 32 Our Work: Programmes and Activities NATIONAL YOUTH ACHIEVEMENT AWARD ASSOCIATION ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The National Youth Achievement Award Association was registered on 12 September 1991 under the Societies Act. The Association was approved as a Charity on 12 October 1991. ROS Registration Number: ROS 238/91 UEN No: S91SS0104L Charity Registration Number: 000840 IPC Registration No: 000721 Registered address: 151 Lorong Chuan #06-01B (Lobby A) New Tech Park Singapore 556741 INTRODUCTION The National Youth Achievement Award (NYAA) was officially launched on 9 May 1992 by the President of the Republic of Singapore at the Istana. ADVISORY BOARD The NYAA Council is advised by an Advisory Board chaired by Mr Heng Swee Keat, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Finance. -

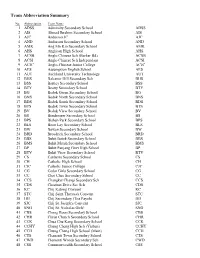

Team Abbreviation Summary

Team Abbreviation Summary No. Abbreviation Team Name 1 ADSS Admiralty Secondary School ADSS 2 AIS Ahmad Ibrahim Secondary School AIS 3 AJC Anderson JC AJC 4 AND Anderson Secondary School AND 5 AMK Ang Mo Kio Secondary School AMK 6 AHS Anglican High School AHS 7 ACSB Anglo Chinese Sch (Barker Rd) ACSB 8 ACSI Anglo Chinese Sch Independant ACSI 9 ACJC Anglo-Chinese Junior College ACJC 10 AES Assumption English School AES 11 AUT Auckland University Technology AUT 12 BHS Balestier Hill Secondary Sch BHS 13 BSS Bartley Secondary School BSS 14 BTY Beatty Secondary School BTY 15 BG Bedok Green Secondary School BG 16 BNS Bedok North Secondary School BNS 17 BDS Bedok South Secondary School BDS 18 BTS Bedok Town Secondary School BTS 19 BV Bedok View Secondary School BV 20 BS Bendemeer Secondary School BS 21 BPS Bishan Park Secondary School BPS 22 BLS Boon Lay Secondary School BLS 23 BW Bowen Secondary School BW 24 BRD Broadrick Secondary School BRD 25 BBS Bukit Batok Secondary School BBS 26 BMS Bukit Merah Secondary School BMS 27 BP Bukit Panjang Govt High School BP 28 BTV Bukit View Secondary School BTV 29 CS Canberra Secondary School CS 30 CH Catholic High School CH 31 CJC Catholic Junior College CJC 32 CG Cedar Girls Secondary School CG 33 CC Chai Chee Secondary School CC 34 CCS Changkat Changi Secondary Sch CCS 35 CDS Chestnut Drive Sec Sch CDS 36 KC Chij Katong Convent KC 37 STC Chij Saint Theresa's Convent STC 38 HIJ Chij Secondary (Toa Payoh) HIJ 39 SJC Chij St. -

1998 Mathematical Olympiads.Pdf

he annual Mathematical Olympiads organized by the Singapore Mathematical Society have successfully concluded this year with the Department of Mathematics, NUS, as a joint organizer. Altogether almost 6000 students from 110 secondary schools, JCs and other organizations took part in the following competitions: the Singapore Secondary School Mathematical Olympiad (SSSMO), Junior and Senior Sections, and the Singapore Mathematical Olympiad (SMO). These competitions took place in June and July at NUS and 12 competition centres around Singapore. More than 190 students received prizes in teams or as individuals in a Prize Presentation Ceremony held on 10 September at NUS from the Guest-of-Honour Mr Peter Chen, Senior Minister of State (Education). In addition, about 270 students received Gold Certificates, about 240 received Silver, and another 510 or so received Bronze. As an encouragement and in recognition of their achievement at this year's IMO held in Taiwan in July, the Singapore Mathematical Society also presented special awards to the 1998 Singapore IMO team at the Prize Presentation Ceremony. The team members comprise: Huah Cheng Jiann (Victoria JC) Awarded Silver Medal at IMO Yeo Keng Hee (Hwa Chong JC) Awarded Bronze Medal at IMO Lin Shaowei (Raffles JC) Awarded Bronze Medal at IMO He Ruimin (Raffles JC) Awarded Bronze Medal at IMO Lim Yee Fun (Victoria JC) Awarded Honorable Mention at IMO Li Hongyi (Raffles JC) Awarded Honorable Mention at IMO The Society would like to thank: (i) Mr Peter Chen, Senior Minister of State (Education), -

2020 Secondary School Posting Booklet

Choosing your Secondary Schools for admission to Secondary to admission 1 in 2021 Secondary for Schools your Choosing www.moe.gov.sg/s1-‐pos.ng Customer Service Centre Tel No. : 6872 2220 CHOOSING YOUR SECONDARY SCHOOLS FOR ADMISSION TO SECONDARY 1 IN 2021 This booklet provides information to help parents and students make more informed secondary school choices in the annual Secondary 1 (S1) Posting. Parents and students can refer to the “Secondary School Education” booklet for more information on secondary education. The information published in this booklet is correct as at time of preparation. This booklet contains proprietary intellectual property of the Government of Singapore (represented by the Ministry of Education) and the Singapore Land Authority. You may not, in whole or in part, in any media or medium (including all digital formats), copy, communicate, broadcast, transmit, photocopy, reproduce, translate, modify, create any derivative work from, or publish over the Internet, the contents of this Booklet without the prior written consent of the Ministry of Education or the Singapore Land Authority, as the case may be. The contents of this booklet is also available at www.moe.gov.sg/s1-posting. Produced by: Ministry of Education Singapore Published September 2020 HOW DOES SECONDARY 1 POSTING WORK? Students are posted to secondary schools based on merit. This means that students with a higher PSLE score will be posted to their school of choice before another Amanda’s School Choices student with a lower score. Vacancies are filled up by students with higher scores first. 1 : School A 4 : School D 2 : School B 5 : School E 3 : School C 6 : School F Let’s look at the posting process by following Amanda, who hadhas submittedsubmitted herher schoolschool choices.choices.