Great Lakes Fish and Wildlife Restoration Act FINAL Project Report Template *Indicates Required Content

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lake Michigan Natural Division Characteristics

The Lake Michigan Natural Division Characteristics Lake Michigan is a dynamic deepwater oligotrophic ecosystem that supports a diverse mix of native and non-native species. Although the watershed, wetlands, and tributaries that drain into the open waters are comprised of a wide variety of habitat types critical to supporting its diverse biological community this section will focus on the open water component of this system. Watershed, wetland, and tributaries issues will be addressed in the Northeastern Morainal Natural Division section. Species diversity, as well as their abundance and distribution, are influenced by a combination of biotic and abiotic factors that define a variety of open water habitat types. Key abiotic factors are depth, temperature, currents, and substrate. Biotic activities, such as increased water clarity associated with zebra mussel filtering activity, also are critical components. Nearshore areas support a diverse fish fauna in which yellow perch, rockbass and smallmouth bass are the more commonly found species in Illinois waters. Largemouth bass, rockbass, and yellow perch are commonly found within boat harbors. A predator-prey complex consisting of five salmonid species and primarily alewives populate the pelagic zone while bloater chubs, sculpin species, and burbot populate the deepwater benthic zone. Challenges Invasive species, substrate loss, and changes in current flow patterns are factors that affect open water habitat. Construction of revetments, groins, and landfills has significantly altered the Illinois shoreline resulting in an immeasurable loss of spawning and nursery habitat. Sea lampreys and alewives were significant factors leading to the demise of lake trout and other native species by the early 1960s. -

Physical Limnology of Saginaw Bay, Lake Huron

PHYSICAL LIMNOLOGY OF SAGINAW BAY, LAKE HURON ALFRED M. BEETON U. S. Bureau of Commercial Fisheries Biological Laboratory Ann Arbor, Michigan STANFORD H. SMITH U. S. Bureau of Commercial Fisheries Biological Laboratory Ann Arbor, Michigan and FRANK H. HOOPER Institute for Fisheries Research Michigan Department of Conservation Ann Arbor, Michigan GREAT LAKES FISHERY COMMISSION 1451 GREEN ROAD ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN SEPTEMBER, 1967 PHYSICAL LIMNOLOGY OF SAGINAW BAY, LAKE HURON1 Alfred M. Beeton, 2 Stanford H. Smith, and Frank F. Hooper3 ABSTRACT Water temperature and the distribution of various chemicals measured during surveys from June 7 to October 30, 1956, reflect a highly variable and rapidly changing circulation in Saginaw Bay, Lake Huron. The circula- tion is influenced strongly by local winds and by the stronger circulation of Lake Huron which frequently causes injections of lake water to the inner extremity of the bay. The circulation patterns determined at six times during 1956 reflect the general characteristics of a marine estuary of the northern hemisphere. The prevailing circulation was counterclockwise; the higher concentrations of solutes from the Saginaw River tended to flow and enter Lake Huron along the south shore; water from Lake Huron entered the northeast section of the bay and had a dominant influence on the water along the north shore of the bay. The concentrations of major ions varied little with depth, but a decrease from the inner bay toward Lake Huron reflected the dilution of Saginaw River water as it moved out of the bay. Concentrations in the outer bay were not much greater than in Lake Huronproper. -

Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary

www.thunderbay.noaa.gov (989) 356-8805 Alpena, MI49707 500 WestFletcherStreet Heritage Center Great LakesMaritime Contact Information N T ATIONAL ATIONAL HUNDER 83°30'W 83°15'W 83°00'W New Presque Isle Lighthouse Park M North Bay ARINE Wreck 82°45'W Old Presque Isle Lighthouse Park B S ANCTUARY North Albany Point Cornelia B. AY Windiate Albany • Types ofVesselsLostatThunderBay South Albany Point Sail Powered • • • Scows Ships, Brigs, Schooners Barks Lake Esau Grand Norman Island Wreck Point Presque Isle Lotus Lake Typo Lake of the Florida • Woods Steam Powered Brown • • Island Sidewheelers Propellers John J. Grand Audubon LAKE Lake iver R ll e B HURON Whiskey False Presque Isle Point • Other • • Unpowered Combustion Motor Powered 45°15'N 45°15'N Bell Czar Bolton Point Besser State Besser Bell Natural Area Wreck Defiance (by quantityoflossforallwrecks) Cargoes LostatThunderBay • • • • Iron ore Grain Coal Lumber products Ferron Point Mackinaw State Forest Dump Scow Rockport • • • • 23 Middle Island Sinkhole Fish Salt Package freight Stone Long Portsmouth Lake Middle Island Middle Island Lighthouse Middle Lake • • • Copper ore Passengers Steel Monaghan Point New Orleans 220 Long Lake Creek Morris D.M. Wilson Bay William A. Young South Ninemile Point Explore theThunderBayNationalMarineSanctuary Fall Creek Salvage Barge &Bathymetry Topography Lincoln Bay Nordmeer Contours inmeters Grass Lake Mackinaw State Forest Huron Bay 0 Maid of the Mist Roberts Cove N Stoneycroft Point or we gi an El Cajon Bay Ogarita t 23 Cre Fourmile Mackinaw State -

AN OVERVIEW of the GEOLOGY of the GREAT LAKES BASIN by Theodore J

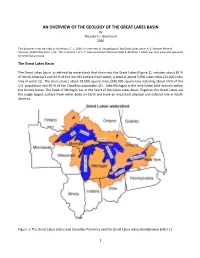

AN OVERVIEW OF THE GEOLOGY OF THE GREAT LAKES BASIN by Theodore J. Bornhorst 2016 This document may be cited as: Bornhorst, T. J., 2016, An overview of the geology of the Great Lakes basin: A. E. Seaman Mineral Museum, Web Publication 1, 8p. This is version 1 of A. E. Seaman Mineral Museum Web Publication 1 which was only internally reviewed for technical accuracy. The Great Lakes Basin The Great Lakes basin, as defined by watersheds that drain into the Great Lakes (Figure 1), includes about 85 % of North America’s and 20 % of the world’s surface fresh water, a total of about 5,500 cubic miles (23,000 cubic km) of water (1). The basin covers about 94,000 square miles (240,000 square km) including about 10 % of the U.S. population and 30 % of the Canadian population (1). Lake Michigan is the only Great Lake entirely within the United States. The State of Michigan lies at the heart of the Great Lakes basin. Together the Great Lakes are the single largest surface fresh water body on Earth and have an important physical and cultural role in North America. Figure 1: The Great Lakes states and Canadian Provinces and the Great Lakes watershed (brown) (after 1). 1 Precambrian Bedrock Geology The bedrock geology of the Great Lakes basin can be subdivided into rocks of Precambrian and Phanerozoic (Figure 2). The Precambrian of the Great Lakes basin is the result of three major episodes with each followed by a long period of erosion (2, 3). Figure 2: Generalized Precambrian bedrock geologic map of the Great Lakes basin. -

Status and Extent of Aquatic Protected Areas in the Great Lakes

Status and Extent of Aquatic Protected Areas in the Great Lakes Scott R. Parker, Nicholas E. Mandrak, Jeff D. Truscott, Patrick L. Lawrence, Dan Kraus, Graham Bryan, and Mike Molnar Introduction The Laurentian Great Lakes are immensely important to the environmental, economic, and social well-being of both Canada and the United States (US). They form the largest surface freshwater system in the world. At over 30,000 km long, their mainland and island coastline is comparable in length to that of the contiguous US marine coastline (Government of Canada and USEPA 1995; Gronewold et al. 2013). With thousands of native species, including many endemics, the lakes are rich in biodiversity (Pearsall 2013). However, over the last century the Great Lakes have experienced profound human-caused changes, includ- ing those associated with land use changes, contaminants, invasive species, climate change, over-fishing, and habitat loss (e.g., Bunnell et al. 2014; Smith et al. 2015). It is a challenging context in terms of conservation, especially within protected areas established to safeguard species and their habitat. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), a protected area is “a clearly defined geographical space, recognised, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associat- ed ecosystem services and cultural values” (Dudley 2008). Depending on the management goals, protected areas can span the spectrum of IUCN categories from highly protected no- take reserves to multiple-use areas (Table 1). The potential values and benefits of protected areas are well established, including conserving biodiversity; protecting ecosystem structures and functions; being a focal point and context for public engagement, education, and good governance; supporting nature-based recreation and tourism; acting as a control or reference site for scientific research; providing a positive spill-over effect for fisheries; and helping to mitigate and adapt to climate change (e.g., Lemieux et al. -

Saginaw River/Bay Fish & Wildlife Habitat BUI Removal Documentation

UNITED STATES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY REGION 5 77 WEST JACKSON BOULEVARD CHICAGO, IL 60604-3590 6 MAY 2014 REPLY TO THE ATTENTION OF Mr. Roger Eberhardt Acting Deputy Director, Office of the Great Lakes Michigan Department of Environmental Quality 525 West Allegan P.O. Box 30473 Lansing, Michigan 48909-7773 Dear Roger: Thank you for your February 6, 2014, request to remove the "Loss of Fish and Wildlife Habitat" Beneficial Use Impairment (BUI) from the Saginaw River/Bay Area of Concern (AOC) in Michigan, As you know, we share your desire to restore all of the Great Lakes AOCs and to formally delist them. Based upon a review of your submittal and the supporting data, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency hereby approves your BUI removal request for the Saginaw River/Bay AOC, EPA will notify the International Joint Commission of this significant positive environmental change at this AOC. We congratulate you and your staff, as well as the many federal, state, and local partners who have worked so hard and been instrumental in achieving this important environmental improvement. Removal of this BUI will benefit not only the people who live and work in the Saginaw River/Bay AOC, but all the residents of Michigan and the Great Lakes basin as well. We look forward to the continuation of this important and productive relationship with your agency and the local coordinating committee as we work together to fully restore all of Michigan's AOCs. If you have any further questions, please contact me at (312) 353-4891, or your staff may contact John Perrecone, at (312) 353-1149. -

Misery Bay Chapter 2

Existing Conditions The first step in developing a plan to protect the coastal resources of Misery Bay is to establish an accurate representation of existing cultural and environmental features within the study area. This chapter will present a series of maps and associated text to describe key features such as owner type, land uses, vegetation cover types, soils and geology. NEMCOG used information and digital data sets from the Center for Geographic Information, State of Michigan, Michigan Resource Information System, Alpena Township, Alpena County, Natural Resource Conservation Service, and U.S. Geological Survey. Information from the Alpena County Master Plan and Alpena Township Master Plan was used to develop a profile of existing conditions. Field surveys were conducted during 2003. Community Demographics Trends in population and housing characteristics can provide an understanding of growth pressures in a community. Population trends from 1900 and 2000 are summarized in Table 2.1. Population levels have risen and fallen twice in the last 100 years, first in the early part of the century and again in the 1980’s. The 1980 US Census recorded the largest population for Alpena Township and Alpena County at 10,152 and 32,315 respectively. During the 80’s decade, population fell by over five percent and has not climbed back to the 1980 US Census level. Table 2.1 Population Trends Alpena Township and Alpena County, 1900-2000 Alpena Township Alpena County Year Population % Change Population % Change 1900 1,173 --- 18,254 --- 1910 928 -20.9% 19,965 +9.4% 1920 701 -24.5% 17,869 -10.5% 1930 813 +16.0% 18,574 +3.9% 1940 1,675 +106.0% 20,766 +11.8% 1950 2,932 +75.0% 22,189 +6.9% 1960 6,616 +125.6% 28,556 +28.7% 1970 9,001 +36.0% 30,708 +7.5% 1980 10,152 +12.8% 32,315 +5.2% 1990 9,602 -5.4% 30,605 -5.3% 2000 9,788 +1.9% 31,314 +2.3% Source: U.S. -

Mackinac County

MACKINAC COUNTY S o y C h r t o u Rock r u BETTY B DORGANS w C t d 8 Mile R D n 6 mlet h o i C d t H o y G r e e Island LANDING 4 CROSSING B u N a Y o d Rd R R R 4 e 8 Mile e y 4 1 k t R k d n 2 ix d t S 14 7 r i Advance n p n 17 d i m Unknow d o e a F u 5 C 123 t e T 7 x k d y O l a o s e i R i R 1 Ibo Rd 1 r r e r Sugar d C M o d Island R a e d R 4 p y f e D c E e S l e n N e i 4 C r a R E R o Y d R L 221 e v a i l 7 R h d A i w x d N i C n S a e w r d g d p e n s u d p 5 a c o r R a r t e B U d d T Island in t g G i e e a n r i g l R R n i o R a d e e R r Rd d o C C o e d d 9 Mile e c 4 r r g k P r h d a L M e n M t h R v B W R R e s e 2 r R C R O s n p N s l k n RACO ea l e u l 28 o ROSEDALE n i R C C d 1 y C l i ree a e le Rd e k a U d e v i 9 Mi e o S y r S a re e d i n g C R R Seney k t ek N e r h C Shingle Bay o U e i u C s R D r e U essea S Sugar B d e F s h k c n c i MCPHEES R L n o e f a a r s t P x h B y e d ut a k 3 So i r k i f u R e t o 0 n h a O t t 1 3 R r R d r r A h l R LANDING 3 M le 7 7 s i T o 1 E d 0 M n i 1 C w a S t U i w e a o s a kn ECKERMAN t R R r v k C o n I Twp r C B U i s Superior e e Island h d d e b Mile Rd r d d Mile Rd 10 e a S f 10 o e i r r q l n s k i W c h n d C u F 3 Columbus u T l McMillan Twp ens M g C g a h r t E a h r 5 Mo reek R n E T 9 H H q m REXFORD c e i u a DAFTER n R W r a l k 5 o M r v Twp Y m r h m L e e C p e i e Twp F s e STRONGS d i Dafter Twp H ty Road 462 East R t d e a Coun P n e e S n e r e v o v o s l d C i R m s n d T o Twp h R t Chippewa l p R C r e NEWBERRY U o e R a n A -

Line 5 Straits of Mackinac Summary When Michigan Was Granted

Line 5 Straits of Mackinac Summary When Michigan was granted statehood on January 26, 1837, Michigan also acquired ownership of the Great Lakes' bottomlands under the equal footing doctrine.1 However before Michigan could become a state, the United States first had to acquire title from us (Ottawa and Chippewa bands) because Anglo-American law acknowledged that we owned legal title as the aboriginal occupants of the territory we occupied. But when we agreed to cede legal title to the United States in the March 28, 1836 Treaty of Washington ("1836 Treaty", 7 Stat. 491), we reserved fishing, hunting and gathering rights. Therefore, Michigan's ownership of both the lands and Great Lakes waters within the cession area of the 1836 Treaty was burdened with preexisting trust obligations with respect to our treaty-reserved resources. First, the public trust doctrine imposes a duty (trust responsibility) upon Michigan to protect the public trust in the resources dependent upon the quality of the Great Lakes water.2 In addition, Art. IV, § 52 of Michigan's Constitution says "conservation…of the natural resources of the state are hereby declared to be of paramount public concern…" and then mandates the legislature to "provide for the protection of the air, water and other natural resources from 3 pollution, impairment and destruction." 1 The State of Michigan acquired title to these bottomlands in its sovereign capacity upon admission to the Union and holds them in trust for the benefit of the people of Michigan. Illinois Central Railroad Co. v. Illinois, 146 U.S. 387, 434-35 (1892); Nedtweg v. -

History of the Lake St. Clair Fisheries Research Station, 1966 - 2003

DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES History of the Lake St. Clair Fisheries Research Station, 1966 - 2003 Mike Thomas, Research Biologist (retired) and Todd Wills, Area Station Manager Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] The Lake St. Clair Great Lakes Station was constructed on a confined dredge disposal site at the mouth of the Clinton River and opened for business in 1974. In this photo, the Great Lakes Station (red roof) is visible in the background behind the lighter colored Macomb County Sheriff Marine Division Office. Lake St. Clair Fisheries Research Station Website: http://www.michigan.gov/dnr/0,4570,7-153-10364_52259_10951_11304---,00.html FISHERIES DIVISION LSCFRS History - 1 History of the Lake St. Clair Fisheries Research Station, 1966-2003 Preface: the other “old” guys at the station. It is my From 1992 to 2016, it was my privilege to hope that this “report” will be updated serve as a fisheries research biologist at the periodically by Station crew members who Lake St. Clair Fisheries Research Station have an interest in making sure that the (LSCFRS). During my time at the station, I past isn’t forgotten. – Mike Thomas learned that there was a rich history of fisheries research and assessment work The Beginning - 1966-1971: that was largely undocumented by the By 1960, Great Lakes fish populations and standard reports or scientific journal the fisheries they supported had been publications. This history, often referred to decimated by degraded habitat, invasive as “institutional memory”, existed mainly in species, and commercial overfishing. The the memories of station employees, in invasive alewife was overabundant and vessel logs, in old 35mm slides and prints, massive die-offs ruined Michigan beaches. -

Detroit River Group in the Michigan Basin

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 133 September 1951 DETROIT RIVER GROUP IN THE MICHIGAN BASIN By Kenneth K. Landes UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Oscar L. Chapman, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director Washington, D. C. Free on application to the Geological Survey, Washington 25, D. C. CONTENTS Page Page Introduction............................ ^ Amherstburg formation................. 7 Nomenclature of the Detroit River Structural geology...................... 14 group................................ i Geologic history ....................... ^4 Detroit River group..................... 3 Economic geology...................... 19 Lucas formation....................... 3 Reference cited........................ 21 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1. Location of wells and cross sections used in the study .......................... ii 2. Correlation chart . ..................................... 2 3. Cross sections A-«kf to 3-G1 inclusive . ......................;.............. 4 4. Facies map of basal part of Dundee formation. ................................. 5 5. Aggregate thickness of salt beds in the Lucas formation. ........................ 8 6. Thickness map of Lucas formation. ........................................... 10 7. Thickness map of Amherstburg formation (including Sylvania sandstone member. 11 8. Lime stone/dolomite facies map of Amherstburg formation ...................... 13 9. Thickness of Sylvania sandstone member of Amherstburg formation.............. 15 10. Boundary of the Bois Blanc formation in southwestern Michigan. -

Biodiversity of Michigan's Great Lakes Islands

FILE COPY DO NOT REMOVE Biodiversity of Michigan’s Great Lakes Islands Knowledge, Threats and Protection Judith D. Soule Conservation Research Biologist April 5, 1993 Report for: Land and Water Management Division (CZM Contract 14C-309-3) Prepared by: Michigan Natural Features Inventory Stevens T. Mason Building P.O. Box 30028 Lansing, MI 48909 (517) 3734552 1993-10 F A report of the Michigan Department of Natural Resources pursuant to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award No. 309-3 BIODWERSITY OF MICHIGAN’S GREAT LAKES ISLANDS Knowledge, Threats and Protection by Judith D. Soule Conservation Research Biologist Prepared by Michigan Natural Features Inventory Fifth floor, Mason Building P.O. Box 30023 Lansing, Michigan 48909 April 5, 1993 for Michigan Department of Natural Resources Land and Water Management Division Coastal Zone Management Program Contract # 14C-309-3 CL] = CD C] t2 CL] C] CL] CD = C = CZJ C] C] C] C] C] C] .TABLE Of CONThNTS TABLE OF CONTENTS I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY iii INTRODUCTION 1 HISTORY AND PHYSICAL RESOURCES 4 Geology and post-glacial history 4 Size, isolation, and climate 6 Human history 7 BIODWERSITY OF THE ISLANDS 8 Rare animals 8 Waterfowl values 8 Other birds and fish 9 Unique plants 10 Shoreline natural communities 10 Threatened, endangered, and exemplary natural features 10 OVERVIEW OF RESEARCH ON MICHIGAN’S GREAT LAKES ISLANDS 13 Island research values 13 Examples of biological research on islands 13 Moose 13 Wolves 14 Deer 14 Colonial nesting waterbirds 14 Island biogeography studies 15 Predator-prey