Fallible New Testament Prophecy/Prophets? a Critique of Wayne Grudem's Hypothesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Examination of Three Recent Philosophical Arguments Against Hierarchy in the Immanent Trinity

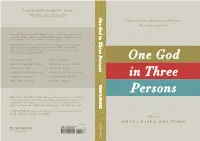

“A profoundly insightful book.” –Sam Storms, Lead Pastor for Preaching and Vision, Bridgeway Church, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma One GodOne in Three Persons Unity of Essence, Distinction of Persons, Implications for Life How do the three persons of the Trinity relate to each other? Evangelicals continue to wrestle with this complex issue and its implications for our understanding of men’s and women’s roles in both the home and the church. Challenging feminist theologies that view the Trinity as a model for evangelical egalitarianism, One God in Three Persons turns to the Bible, church history, philosophy, and systematic theology to argue for the eternal submission of the Son to the Father. Contributors include: WAYNE GRUDEM JOHN STARKE One God CHRISTOPHER W. COWAN MICHAEL A. G. HAYKIN KYLE CLAUNCH PHILIP R. GONS JAMES M. HAMILTON JR. ANDREW DAVID NASELLI ROBERT LETHAM K. SCOTT OLIPHINT in Three MICHAEL J. OVEY BRUCE A. WARE WARE & STARK E Persons BRUCE A. WARE (PhD, Fuller Theological Seminary) is professor of Christian theology at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. He has written numerous journal articles, book chapters, book reviews, and books, including God’s Lesser Glory; God’s Greater Glory; Father, Son, and Holy Spirit; and The Man Christ Jesus. JOHN STARKE serves as preaching pastor at Apostles Church in New York City. He and his wife, Jena, have four children. Edited by BRUCE A. WARE & JOHN STARKE THEOLOGY ISBN-13: 978-1-4335-2842-2 ISBN-10: 1-4335-2842-8 5 2 1 9 9 9 7 8 1 4 3 3 5 2 8 4 2 2 U.S. -

6 Election and Reprobation (Predestination)

ELECTION AND REPROBATION (PREDESTINATION) The biblical doctrine of election is that before Creation God selected out of the human race, foreseen as fallen, those whom he would redeem, bring to faith, justify, and glorify in and through Jesus Christ. This divine choice is an expression of free and sovereign grace, for it is unconstrained and unconditional, not merited by anything in those who are its subjects. God owes sinners no mercy of any kind, only condemnation; so it is a wonder, and matter for endless praise, that he should choose to save any of us; and doubly so when his choice involved the giving of his own Son to suffer as sin-bearer for the elect.15 (J. I. Packer) [Election] signifies to single out, to select, to choose, to take one and leave another. Election means that God has singled out certain ones to be the objects of His saving grace, while others are left to suffer the just punishment of their sins. It means that before the foundation of the world, God chose out of the mass of our fallen humanity a certain number and predestinated them to be conformed to the image of His Son.16 (A. W. Pink) We shall never be clearly persuaded, as we ought to be, that our salvation flows from the wellspring of God’s free mercy until we come to know his eternal election, which illumines God’s grace by this contrast: that he does not indiscriminately adopt all into the hope of salvation but gives to some what he denies to others.17 (John Calvin) Election is an act of God before creation in which he chooses some people to be saved, not on account of any foreseen merit in them, but only because of his sovereign good pleasure.18 (Wayne Grudem) What does the Bible teach about election/predestination? Simeon has related how God first visited the Gentiles, to take from them a people for his name. -

How “Complementarians” Have Corrupted Communication Kevin Giles

The Genesis of Confusion: How “Complementarians” Have Corrupted Communication Kevin Giles In the previous edition of Priscilla Papers, my article, “The Genesis harmless. Carefully choosing words to conceal what is actually being of Equality,” outlined the prevailing view that the Bible’s opening taught and to surreptitiously further one’s own agenda, I believe, is chapters make substantial or essential equality of the two sexes the morally wrong. One important responsibility of theologians is to creation ideal, and that the subordination of women is entirely a bring clarity to the issues they address, in part by carefully defining consequence of the fall. I further noted that Pope John Paul II made and consistently using key terms. To write theology in order to this interpretation of Gen 1–3 binding on Roman Catholics. In conceal seems to me perverse. Should not Christians communicate this essay, I move on to discuss four key terms—“role,” “equality,” with each other openly and honestly? “difference,” and “complementary”—which “complementarians” consistently utilize to give a different interpretation of Gen 1–3 and The origins of this obfuscating language of other biblical texts important to their cause. Again, I bring in the For long centuries, how the man-woman relationship was to be Roman Catholic voice to give a wider perspective.1 understood was openly stated and crystal clear. God had made In the mid-1960s, I studied at Moore Theological College Sydney, men “superior,” women “inferior.”6 Woman was created second, a large, evangelical and Reformed seminary. In my four years after man, thus women are second in rank. -

Campus Crusade Institute of Biblical Studies Winter Park, FL

Campus Crusade Institute of Biblical Studies Winter Park, FL CHRISTIAN THEOLOGY: HUMANITY, SIN, CHRIST, SALVATION June 30-July 11, 2014 9:00-11:00 am Ryan M. Reeves, Course Instructor [email protected] Associate Professor of Historical Theology and Dean Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary Jacksonville, Florida SYLLABUS COURSE DESCRIPTION A survey of and introduction to the Christian doctrines of humanity, sin, the person and work of Christ, and salvation. One hour. OBJECTIVE To better understand and appreciate the aforementioned doctrines as they are revealed in Holy Scripture and confessed by the church in order that we may better live our lives to the glory of the triune God. REQUIRED TEXT Wayne Grudem, Systematic Theology. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1994. REQUIREMENTS 1. Reading (20%) All students are required to read chapters 21-25, 26-29, 31-38, 40-43 in Grudem’s Systematic Theology. Reading should be done thoroughly and thoughtfully, with a sincere attempt to learn all one can from this reading. Turn in Reading Report Form on July 11 indicating the amount of reading completed by each reading due date. 2. Scripture Meditation (20%) A much-neglected discipline of the Christian life and theology is Scripture meditation. Essentially, Scripture meditation involves (1) a continuous process of remembering and musing over Scripture's teaching, and (2) a reassessment and a reshaping of one's life in light of that teaching. In this course, we will encourage growth in this discipline by engaging our minds and hearts in some consistent, but non-burdensome, Scripture meditation. For these two weeks, we will commit ourselves to reading thoughtfully and prayerfully (preferably out loud) some assigned Scripture passage. -

Revisiting Wayne Grudem's Two Levels of New Testament Prophecy

The Continuation of NT Prophecy and a Closed Canon: Revisiting Wayne Grudem’s Two Levels of New Testament Prophecy By Dr. R. Bruce Compton Professor of Biblical Languages and Exposition Detroit Baptist Theological Seminary INTRODUCTION A key sticking point that continues to divide evangelicals is the question over the cessation versus the continuation of New Testament prophecy.1 At the heart of the debate are the issues of a closed canon and the New Testament’s role as the final rule for faith and practice. A number of evangelicals posit two levels of prophecy: an apostolic level that is inerrant and divinely authoritative and a non-apostolic level that is neither. These further argue that, since only the non-apostolic level continues beyond the writing of the New Testament, the canon is not threatened and remains the final rule for faith and practice.2 Wayne Grudem’s The Gift of Prophecy in the New Testament and Today, is commonly recognized as laying the exegetical foundation for two levels of prophecy and for the continuation of the non-apostolic level in harmony with a closed canon.3 For that reason, the 1 The controversy surrounding NT prophecy is part of a larger debate over the cessation versus the continuation of miraculous gifts. In support of cessationism, see, for example, Richard B. Gaffin, Jr., “Cessationist,” in Are Miraculous Gifts for Today? Four Views, ed. Wayne A. Grudem (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1996), 25–64; Myron J. Houghton, “A Reexamination of 1 Corinthians 13:8–13,” Bibliotheca Sacra 153 (July–September 1996): 344–56; R. -

7-Theology-Trinity.Pdf

1 Dr. Rick Bartosik Lecture Series: The Doctrine of God Lecture 7: “The Trinity” THE TRINITY (The following outline is adapted from Wayne Grudem, Systematic Theology, Chapter 14: “God in Three Persons: The Trinity”) Introduction: The doctrine of the Trinity is one of the most important doctrines of the Christian faith. It answers the question: “What is God like in himself?” The biblical teaching on the Trinity tells us that all of God’s attributes are true of all three persons (Father, Son and Holy Spirit) for each is fully God. Definition: “God eternally exists as three persons, Father, Son and Holy Spirit, and each person is fully God, and there is one God.” (Wayne Grudem, Systematic Theology, 226). Meaning: The word “trinity” means “tri-unity” or “three-in-oneness.” It summarizes the teaching of the Bible that God exists as three persons, yet he is one God. BIBLICAL BASIS FOR THE DOCTRINE OF THE TRINITY A. The Doctrine of the Trinity Progressively Revealed in the Bible Partial Revelation of the Trinity in the Old Testament Old Testament passages implying that God exists as more than one person Genesis 1:26 Genesis 3:22 Genesis 11:7 Isaiah 6:8 Old Testament passages where one person is called “God” or “Lord” and is distinguished from another person also said to be God Psalm 45:6-7 (Heb. 1:8) Psalm 110:1 (Matt. 22:41-46) Isaiah 63:10 Isaiah 61:1 Malachi 3:1-2 Isaiah 48:16 Old Testament passages about “the angel of the LORD” who is distinct from the LORD himself and yet is called “God” or LORD” 2 Genesis 16:13 Exodus 3:2-6 Exodus 23:20-22 Numbers 22:35, 38 Judges 2:1-2; 6:11 Proverbs 8:22-31 “created” in verse 22 not bara “to create” but qanah “to get, acquire.” Indicates God began to direct and make use of the powerful creative work of the Son in creation. -

Dr. David W. Chapman Professor of New Testament and Archaeology

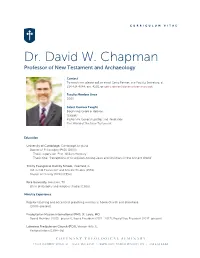

CURRICULUM VITAE Dr. David W. Chapman Professor of New Testament and Archaeology Contact To reach me, please call or email Gerry Reimer, our Faculty Secretary, at 314.434.4044, ext. 4201, or [email protected] Faculty Member Since 2000 Select Courses Taught Beginning Greek & Hebrew Gospels Pastoral & General Epistles and Revelation The World of the New Testament Education University of Cambridge, Cambridge, England Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) (2000) Thesis supervisor: Prof. William Horbury Thesis title: “Perceptions of Crucifixion Among Jews and Christians in the Ancient World” Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, Deerfield, IL MA in Old Testament and Semitic Studies (1996) Master of Divinity (MDiv) (1996) Rice University, Houston, TX BA in philosophy and religious studies (1988) Ministry Experience Regular teaching and occasional preaching ministry at home church and elsewhere (2000–present) Presbyterian Mission International (PMI), St. Louis, MO Board Member (2005–present); Board President (2011–2017); Board Vice President (2017–present) Lakeview Presbyterian Church (PCA), Vernon Hills, IL Pastoral Intern (1994–95) COVENANT THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY 12330 CONWAY ROAD, ST. LOUIS, MO 63141 • WWW.COVENANTSEMINARY.EDU • 314.434.4044 Student Ministries, Inc., Deerfield, IL Ministry Affiliate (1993–96) Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA Campus Crusade for Christ (Campus Staff (1989–93) Teaching Experience Covenant Theological Seminary, St. Louis, MO Professor of New Testament and Archaeology (2013–present) Associate Professor -

Calvinist, Arminian, and Baptist Perspectives on Soteriology CONTENTS Journal for Baptist Theology and Ministry SPRING 2011 • Vol

SPRING 2011 • VOLUME 8, NUMBER 1 Calvinist, Arminian, and Baptist Perspectives on Soteriology CONTENTS Journal for Baptist Theology and Ministry SPRING 2011 • Vol. 8, No. 1 © The Baptist Center for Theology and Ministry Editor-in-Chief Associate Editor Assistant Editor Charles S. Kelley, Th.D. Christopher J. Black, Ph.D. Suzanne Davis Executive Editor & Book Review Editors Design and Layout Editors BCTM Director Page Brooks, Ph.D. Frank Michael McCormack Steve W. Lemke, Ph.D. Archie England, Ph.D. Gary D. Myers Dennis Phelps, Ph.D. Calvinist, Arminian, and Baptist Perspectives on Soteriology EDITORIAL INTRODUCTION Calvinist, Arminian, and Baptist Perspectives on Soteriology 1 Steve W. Lemke PART I: THOMAS GRANTHAM’S VIEW OF SALVATION Thomas Grantham’s Theology of the Atonement and Justification 7 J. Matthew Pinson RESPONSE to J. Matthew Pinson’s “Thomas Grantham’s Theology of the Atonement and Justification” 22 Rhyne Putman RESPONSE to J. Matthew Pinson’s “Thomas Grantham’s Theology of the Atonement and Justification” 25 Clint Bass RESPONSE to J. Matthew Pinson’s “Thomas Grantham’s Theology of the Atonement and Justification” 29 James Leonard RESPONSE to Panel 34 Matthew Pinson CONTENTS PART II: CALVINIST AND BAPTIST SOTERIOLOGY The Doctrine of Regeneration in Evangelical Theology: The Reformation to 1800 42 Kenneth Stewart The Bible’s Storyline: How it Affects the Doctrine of Salvation 59 Heather A. Kendall Calvinism and Problematic Readings of New Testament Texts 69 Glen Shellrude Beyond Calvinism and Arminianism: Toward a Baptist Soteriology 87 Eric Hankins Joe McKeever’s Cartoon 101 Book Reviews 102 Reflections 127 Back Issues 128 The Baptist Center for Theology and Ministry is a research institute of New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary. -

Andreas J. Köstenberger & Justin Taylor

Pantone 10112 C + 2X Black (Pantone) WALK WITH JESUS DURING HIS THE MOST IMPORTANT WEEK OF THE LAST WEEK ON EARTH MOST IMPORTANT PERSON WHO EVER LIVED On March 29, AD 33, Jesus entered the city of Jerusalem and boldly predicted that he would soon be put to death—executed on a cross, like a common criminal. So began the most important week of the most important person who ever lived. Nearly 2,000 years later, the events that took place during Jesus’s last days still reverberate through the ages. Designed as a day-by-day guide to Passion Week, The Final Days of Jesus leads us to reexamine and meditate on the history-making, earth-shaking significance of Jesus’s arrest, trial, crucifixion, and empty tomb. Combining a chronological arrangement of the Gospel accounts with insightful commentary, charts, and maps, this book will help you better understand what actually happened all those years ago—and why it matters today. “If you want to get to know the person and teachings of Jesus in the context of an engaging story with practical commentary, this book is for you.” DARRIN PATRICK, PASTOR, THE JOURNEY, ST. LOUIS, MISSOURI “This is an immensely helpful guide to the last week of Jesus’s life—historically, theologically, and devotionally. A feast of insights for both mind and heart.” MARK STRAUSS, PROFESSOR OF NEW TESTAMENT, BETHEL SEMINARY SAN DIEGO ANDREAS J. KÖSTENBERGER “An enlightening and edifying look at the most important week in history. One gets the sense KÖSTENBERGER & TAYLOR that we should proceed through these pages on our knees.” & JUSTIN TAYLOR J. -

1 “Biblical Evidence for the Eternal Submission of the Son to the Father” Wayne Grudem [Published in the New Evangelical

“Biblical Evidence for the Eternal Submission of the Son to the Father” 1 Wayne Grudem [published in The New Evangelical Subordinationism? edited by Dennis W. Jowers and H. Wayne House (Eugene, OR: Pickwick, 2012), 223-261. ] There is no question that, during the time of Jesus’ life on earth, he was subject to the authority of God the Father. He said, “'Behold, I have come to do your will, O God” (Heb. 10:7). He also said, “My food is to do the will of him who sent me and to accomplish his work” (John 4:34). And he said, “I do nothing on my own authority, but speak just as the Father taught me” (John 8:28). But some evangelicals today claim this was only a temporary submission to the authority of the Father, limited to the time of his earthly life or at least to actions connected to the purpose of earning our salvation.2 They argue that prior to his coming to earth, and after he returned to heaven, God the Son was equal in authority to God the Father. Gilbert Bilezikian writes, The frame of reference for every term that is found in Scripture to describe Christ’s humiliation pertains to his ministry and not to his eternal state.... Because there was no order of subordination within the Trinity prior to the Second Person’s incarnation, there will remain no such thing after its completion. If we must talk of subordination it is only a functional or economic subordination that pertains exclusively to Christ’s role in relation to human history. -

Women and Church Leadership the Central Question: SHOULD SOME GOVERNING and TEACHING ROLES in the CHURCH BE RESTRICTED to MEN?

Nov . 12, 2008 Systematic Theology, Chapter 47 part 2: Women and church leadership The central question: SHOULD SOME GOVERNING AND TEACHING ROLES IN THE CHURCH BE RESTRICTED TO MEN? A. Reaffirmation of equality in personhood and importance, because of equality in the image of God 1. Gen. 1:27: "So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them." 2. Reminder that in the New Testament church, the Holy Spirit is poured out in new fullness on both men and women: Acts 2:17-18; 1 Cor. 12:7, 11 (see Acts 18:26); 1 Pet. 4:10; Acts 8:12; Gal. 3:28 3. Note: Women's gifts and ministries have wrongly been stifled in many evangelical families and churches B. But some governing and teaching roles in the church are restricted to men 1. 1 Timothy 2:11-15 ESV 1 Timothy 2:11 Let a woman learn quietly with all submissiveness. 12 I do not permit a woman to teach or to exercise authority over a man; rather, she is to remain quiet. 13 For Adam was formed first, then Eve; 14 and Adam was not deceived, but the woman was deceived and became a transgressor. 15 Yet she will be saved through childbearing- if they continue in faith and love and holiness, with self-control. a. Setting: the assembled church b. In that setting, women could not teach (=Bible teaching) or have governing authority over the whole church c. Yet the NT views positively other kinds of teaching and other speaking by women (1) Explaining the Bible to anyone in more informal settings: Acts 18:26: [of Apollos:] ESV He began to speak boldly in the synagogue, but when Priscilla and Aquila heard him, they took him and explained to him the way of God more accurately. -

Evangelical Feminism and Biblical Truth an Important Book That Is Urgently Needed

“WHAT DOES THE BIBLE REALLY TEACH Evangelical Feminism ABOUT THE ROLES OF MEN AND WOMEN?” & Biblical Truth Evangelical Feminism Bible scholar Wayne Grudem carefully draws on 27 years of biblical research as he responds to 118 arguments often levied against traditional gender roles. Grudem counters egalitarian and feminist critiques with & Biblical Truth clarity, compassion, and precision, showing God’s equal value for men and women while celebrating the beauty in their differences. “After the Bible, I cannot imagine a more useful book for finding AN ANALYSIS OF MORE reliable help in understanding God’s will for manhood and womanhood in the church and the home.” THAN 100 DISPUTED QUESTIONS JOHN PIP ER, Pastor for Preaching and Vision, Bethlehem Baptist Church, Twin Cities, Minnesota “A fair, thorough, warmhearted treatment of one of the most N ANCY L EIGH D E M OSS, radio host, Revive Our Hearts calls the church of Jesus Christ back to the Scriptures. Remarkably, almost every question a reader might have on this subject is answered here. This book is a treasure and a resource demonstrating that the complementarian view is biblical and beautiful.” T HOMAS R . S CHREINER, Professor of New Testament, The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary “Laboriously and exhaustively, with clarity, charity, and a scholar’s ob- jectivity, Wayne Grudem sifts through current challenges to the Bible’s apparent teaching on men and women. This is the fullest and most infor- mative analysis available, and no one will be able to deny the cumulative strength of the case this author makes, as he vindicates the older paths.” J.I .