Chapter 5 Combatants As Victims of Crimes Against Humanity Suitable

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Defending the Emergence of the Superior Orders Defense in the Contemporary Context

Goettingen Journal of International Law 2 (2010) 3, 871-892 Defending the Emergence of the Superior Orders Defense in the Contemporary Context Jessica Liang Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................ 872 A. Introduction .......................................................................................... 872 B. Superior Orders and the Soldier‘s Dilemma ........................................ 872 C. A Brief History of the Superior Orders Defense under International Law ............................................................................................. 874 D. Alternative Degrees of Attributing Criminal Responsibility: Finding the Right Solution to the Soldier‘s Dilemma ..................................... 878 I. Absolute Defense ................................................................................. 878 II. Absolute Liability................................................................................. 880 III.Conditional Liability ............................................................................ 881 1. Manifest Illegality ..................................................................... 881 2. A Reasonableness Standard ...................................................... 885 E. Frontiers of the Defense: Obedience to Civilian Orders? .................... 889 I. Operation under the Rome Statute ....................................................... 889 II. How far should the Defense of Superior Orders -

Nuremberg Academy Annual Report 2018

Annual Report International Nuremberg Principles Academy 1 Imprint The Annual Report 2018 has been Executive Board: published by the International Klaus Rackwitz (Director), Nuremberg Principles Academy. Dr. Viviane Dittrich (Deputy Director) It is available in English, German Edited by: and French and can be ordered Evelyn Müller at [email protected] Layout: or be downloaded on the website Martin Küchle Kommunikationsdesign www.nurembergacademy.org. Photos: Egidienplatz 23 International Nuremberg Principles Academy 90403 Nuremberg, Germany p. 9 Strathmore University, p. 20 Wayamo T + 49 (0) 911.231.10379 Foundation F + 49 (0) 911.231.14020 Printed by: [email protected] Druckwerk oHG Table of Contents 2 Foreword 5 The International Nuremberg Principles Academy 7 A Forum for Dialogue 8 • Events 14 • Network and Cooperation 19 Capacity Building 25 Research 29 Publications and Resources 32 Communications 34 Organization 37 Partners and Sponsors We proudly present the second edition of the Annual Report of the International Nuremberg Principles Academy. It reflects the activities and the achieve ments of the Nuremberg Academy throughout the year of 2018. It was another year of growth for the Nu Foreword remberg Academy with an increased num ber of events and activities at a peak level. Important anniversaries such as the 70th anniversary of the judgment of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in Tokyo and the 20th anniversary of the adoption of the Rome Statute have been reflected in the Academy’s work and activities. Major international conferences – as far as we can see the largest of their kind, dedicated to these important dates worldwide – were held in Nuremberg in May and in October. -

Nuremberg Icj Timeline 1474-1868

NUREMBERG ICJ TIMELINE 1474-1868 1474 Trial of Peter von Hagenbach In connection with offenses committed while governing ter- ritory in the Upper Alsace region on behalf of the Duke of 1625 Hugo Grotius Publishes On the Law of Burgundy, Peter von Hagenbach is tried and sentenced to death War and Peace by an ad hoc tribunal of twenty-eight judges representing differ- ent local polities. The crimes charged, including murder, mass Dutch jurist and philosopher Hugo Grotius, one of the principal rape and the planned extermination of the citizens of Breisach, founders of international law with such works as Mare Liberum are characterized by the prosecution as “trampling under foot (On the Freedom of the Seas), publishes De Jure Belli ac Pacis the laws of God and man.” Considered history’s first interna- (On the Law of War and Peace). Considered his masterpiece, tional war crimes trial, it is noted for rejecting the defense of the book elucidates and secularizes the topic of just war, includ- superior orders and introducing an embryonic version of crimes ing analysis of belligerent status, adequate grounds for initiating against humanity. war and procedures to be followed in the inception, conduct, and conclusion of war. 1758 Emerich de Vattel Lays Foundation for Formulating Crime of Aggression In his seminal treatise The Law of Nations, Swiss jurist Emerich de Vattel alludes to the great guilt of a sovereign who under- 1815 Declaration Relative to the Universal takes an “unjust war” because he is “chargeable with all the Abolition of the Slave Trade evils, all the horrors of the war: all the effusion of blood, the The first international instrument to condemn slavery, the desolation of families, the rapine, the acts of violence, the rav- Declaration Relative to the Universal Abolition of the Slave ages, the conflagrations, are his works and his crimes . -

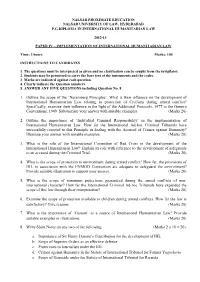

1. Outline the Scope of the 'Nuremberg Principles'. What Is

NALSAR PROXIMATE EDUCATION NALSAR UNIVERSITY OF LAW, HYDERABAD P.G.DIPLOMA IN INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW 2012-13 PAPER IV – IMPLEMENTATION OF INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW Time: 3 hours Marks: 100 INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES 1. The questions must be interpreted as given and no clarification can be sought from the invigilator. 2. Students may be permitted to carry the bare text of the instruments and the codes. 3. Marks are indicated against each question. 4. Clearly indicate the Question numbers. 5. ANSWER ANY FIVE QUESTIONS including Question No. 8 1. Outline the scope of the ‘Nuremberg Principles’. What is their influence on the development of International Humanitarian Law relating to protection of Civilians during armed conflict? Specifically, examine their influence in the light of the Additional Protocols, 1977 to the Geneva Conventions, 1949. Substantiate your answer with suitable examples. (Marks 20) 2. Outline the importance of ‘Individual Criminal Responsibility’ in the implementation of International Humanitarian Law. How far the International Ad-hoc Criminal Tribunals have successfully resorted to this Principle in dealing with the Accused of Crimes against Humanity? Illustrate your answer with suitable examples. (Marks 20) 3. What is the role of the International Committee of Red Cross in the development of the International Humanitarian Law? Explain its role with reference to the development of safeguards to an accused during the Criminal Trial. (Marks 20) 4. What is the scope of protection to environment during armed conflict? How far, the provisions of IHL in association with the ENMOD Convention are adequate to safeguard the environment? Provide suitable illustration to support your answer. -

1. Examine the Impact of the 'Nuremberg Principles' on The

NALSAR PROXIMATE EDUCATION NALSAR UNIVERSITY OF LAW, HYDERABAD P.G.DIPLOMA IN INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW 2009-10 PAPER IV – Implementation of International Humanitarian Law Time: 2 hours and 30 minutes Marks: 75 INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES 1. The questions to be interpreted as given and no clarification can be sought from the invigilator 2. Students may be permitted to carry the bare text of the instruments and the codes. 3. All questions carry equal marks (15 marks each) 4. Clearly indicate the Question numbers ANSWER ANY FIVE QUESTIONS 1. Examine the impact of the ‘Nuremberg Principles’ on the development of IHL in the post Geneva Conventions phase. How far, the Nuremberg Principles have facilitated the implementation of the IHL? Substantiate your answer with suitable examples. 2. Examine the scope of ‘Individual Criminal Responsibility’ as an important principle of International humanitarian law. How far this principle has been invoked at the International Plane for the effective implementation of IHL? Support your answer with suitable examples. 3. Write Short Notes on any three of the following a. Importance of Marten’s Clause b. Principle of Complimentarity c. Protections to witnesses during criminal trial d. Scope of War Crimes in the Statute of International Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia e. Scope of Crimes against in the Statute of International Tribunal for Rwanda 4. Examine the scope of ‘Rape’ as interpreted by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda committed during the course of Non International Armed Conflict. Refer to leading case laws. 5. What is the role of the International Committee of Red Cross in the development of the International Humanitarian Law? Explain its role with reference to the development of safeguards to an accused during the Criminal Trial. -

The Nuremberg Legacy and the International Criminal Court—Lecture in Honor of Whitney R

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Washington University St. Louis: Open Scholarship Washington University Global Studies Law Review Volume 12 Issue 3 The International Criminal Court At Ten (Symposium) 2013 The Nuremberg Legacy and the International Criminal Court—Lecture in Honor of Whitney R. Harris, Former Nuremberg Prosecutor Hans-Peter Kaul International Criminal Court (ICC) Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies Part of the Courts Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, International Law Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation Hans-Peter Kaul, The Nuremberg Legacy and the International Criminal Court—Lecture in Honor of Whitney R. Harris, Former Nuremberg Prosecutor, 12 WASH. U. GLOBAL STUD. L. REV. 637 (2013), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies/vol12/iss3/18 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Global Studies Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NUREMBERG LEGACY AND THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT— LECTURE IN HONOR OF WHITNEY R. HARRIS, FORMER NUREMBERG PROSECUTOR HANS-PETER KAUL∗∗∗ We are assembled today in honor of Whitney R. Harris, a great American, a great advocate of the rule of law and international justice. We are also assembled here today, and tomorrow, to reflect on the International Criminal Court (ICC) and its fight against impunity until the present day. It is quite a noteworthy coincidence that this year we celebrate both the 100th birthday of Whitney R. -

Pirates and Impunity: Is the Threat of Asylum Claims a Reason to Allow Pirates to Escape Justice

Pirates and Impunity: Is the Threat of Asylum Claims a Reason to Allow Pirates to Escape Justice Yvonne M. Dutton Abstract Pirates are literally getting away with murder. Modern pirates are attacking vessels, hijacking ships at gunpoint, taking hostages, and injuring and killing crew members.1 They are doing so with increasing frequency. According to the International Maritime Bureau (“IMB”) Piracy Reporting Center’s 2009 Annual Report, there were 406 pirate attacks in 2009—a number that has not been reached since 2003. Yet, in most instances, a culture of impunity reigns whereby nations are not holding pirates accountable for the violent crimes they commit. Only a small portion of those people committing piracy are actually captured and brought to trial, as opposed to captured and released. For example, in September 2008, a Danish warship captured ten Somali pirates, but then later released them on a Somali beach, even though the pirates were found with assault weapons and notes stating how they would split their piracy proceeds with warlords on land. Britain’s Royal Navy has been accused of releasing suspected pirates,7 as have Canadian naval forces. Only very recently, Russia released captured Somali pirates—after a high-seas shootout between Russian marines and pirates that had attacked a tanker carrying twenty-three crew and US$52 million worth of oil.9 In May 2010, the United States released ten captured pirates it had been holding for weeks after concluding that its search for a nation to prosecute them was futile. In fact, between March and April 2010, European Union (“EU”) naval forces captured 275 alleged pirates, but only forty face prosecution. -

NUREMBERG) Judgment of 1 October 1946

INTERNATIONAL MILITARY TRIBUNAL (NUREMBERG) Judgment of 1 October 1946 Page numbers in braces refer to IMT, judgment of 1 October 1946, in The Trial of German Major War Criminals. Proceedings of the International Military Tribunal sitting at Nuremberg, Germany , Part 22 (22nd August ,1946 to 1st October, 1946) 1 {iii} THE INTERNATIONAL MILITARY TRIBUNAL IN SESSOIN AT NUREMBERG, GERMANY Before: THE RT. HON. SIR GEOFFREY LAWRENCE (member for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) President THE HON. SIR WILLIAM NORMAN BIRKETT (alternate member for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) MR. FRANCIS BIDDLE (member for the United States of America) JUDGE JOHN J. PARKER (alternate member for the United States of America) M. LE PROFESSEUR DONNEDIEU DE VABRES (member for the French Republic) M. LE CONSEILER FLACO (alternate member for the French Republic) MAJOR-GENERAL I. T. NIKITCHENKO (member for the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) LT.-COLONEL A. F. VOLCHKOV (alternate member for the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) {iv} THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, THE FRENCH REPUBLIC, THE UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND, AND THE UNION OF SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLICS Against: Hermann Wilhelm Göring, Rudolf Hess, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Robert Ley, Wilhelm Keitel, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Alfred Rosenberg, Hans Frank, Wilhelm Frick, Julius Streicher, Walter Funk, Hjalmar Schacht, Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, Karl Dönitz, Erich Raeder, Baldur von Schirach, Fritz Sauckel, Alfred Jodl, Martin -

Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes Against the Polish Nation As a Ground for Prosecution of Crimes Against Humanity, War Crimes and Crimes Against Peace

XXXVIi POLISH YEaRbook of inTERnaTional law DOI 10.7420/pyil2017n 2017 PL ISSN 0554-498X Karolina Wierczyńska* AcT Of 18 DEcEmbEr 1998 ON ThE INSTiTuTE Of NaTiONal REmEmbraNcE – COmmiSSiON fOr ThE PrOSEcuTiON Of CrimES agaiNST ThE POliSh NaTiON aS a grOuNd fOr prOSEcuTiON Of crimES agaiNST humaNiTy, war crimES aNd crimES agaiNST pEacE Abstract: This article discusses definitions of crimes included into the Act of 18 December 1998 on the Institute of National Remembrance – Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation, and their usefulness in prosecuting individuals who committed international crimes. It is argued that the provisions of the Act cannot constitute a ground for criminal responsibility of individuals, as they violate the principle of nullum crimen sine lege certa. Keywords: crimes against humanity, crimes against peace, genocide, ICC, ICTR, Institute of National Remembrance, war crimes INTrOducTiON The current discussion on the Act of 18 December 1998 on the Institute of National Remembrance – Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation (the Act) should have been started many years before adoption of the controversial amendment which has unleashed an international furore, with Poland at the centre. -

The United States Response to Achille Lauro-Questions of Jurisdiction

CONTEMPORARY USES OF FORCE AGAINST TERRORISM: THE UNITED STATES RESPONSE TO A CHILLE LA URO-QUESTIONS OF JURISDICTION AND ITS EXERCISE Jeffrey Allan McCredie* CONTENTS I. FACTUAL BACKGROUND ................................ 436 II. CLAIMS OF JURISDICTION UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW. 437 A. Jurisdiction Over International Crimes .......... 437 B. Crimes Against Humanity ..................... 440 C. The Seizure of the Vessel as an Act of Piracy .. 443 1. United States Practice ..................... 443 2. Piracy Under the Law of Nations .......... 443 3. The Convention on the High Seas ......... 445 4. M odern Piracy ........................... 446 D. Terrorism as an International Crime ........... 450 1. United Nations Efforts. .................... 450 2. Other Modern Efforts ...................... 453 III. CLAIMS TO EXERCISE JURISDICTION BY FORCE ......... 454 A. Current United States Policy .................. 454 B. Restrictions on the Use of Force Under Interna- tional Law ................................... 455 C. Exceptions to the General Prohibitions of the Use of Force ..................................... 457 1. The Right of Self-Defense ................. 457 2. The Doctrine of Intervention and Self-Help. 459 a. Intervention ......................... 459 b. Self-Help ........................... 460 c. The Protection of Nationals Abroad ... 461 d. An Analogy to Hostage Rescue A ttempts ............................ 462 IV. CONCLUSIONS AND PROSPECTS FOR THE FUTURE ....... 465 * Member PA Bar, Assistant District Attorney, Montgomery County, -

The Evolution of Individual Criminal Responsibility Under International Law by EDOARDO GREPPI

RICRSEPTEMBRE IRRCSEPTEMBER 1999 VOL.81 N°835 The evolution of individual criminal responsibility under international law by EDOARDO GREPPI HE international legal provisions on war crimes and crimes against humanity have been adopted and developed within the frame- work of international humanitarian law, or the law of armed Tconflict, a special branch of international law which has its own peculiarities and which has gone through an intense period of growth, evo- lution and consolidation in the last 50 years. The rules of humanitarian law concerning international crimes and responsibility have not always appeared sufEciendy clear. One of the thorniest problems is that relating to the legal nature of international crimes committed by individuals and considered as serious violations of the rules of humanitarian law.1 As regards the traditional tripartition — crimes against EDOARDO GREPPI is Associate Professor of International Law at the University of Turin, Italy, and a member of the International Institute of Humanitarian Law in San Remo. 1 See M. C. Bassiouni/P. Nanda, A Treatise N-Ronzitti- "Crimini intemazionali", Encidopedia on International Criminal Law, Springfield, 1973; 9iuridica, X, 1988; F. Francioni, "Crimini inter- S.G\aser,Droitinternationalpenalconventionnel, mvonati", Digestodelle discipline pubblicistiche, Brussels, 1970-78; G. Sperduti, "Crimini inter- lv- r988- P- 4^4- nazionali", Encidopedia del diritto,Yi, 1962, p. 337; 531 THE EVOLUTION OF INDIVIDUAL CRIMINAL RESPONSIBILITY UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW peace, war crimes and crimes against humanity — this paper will be devoted essentially to the latter two categories, which are more closely linked to the core of international humanitarian law and are of major interest at this tormented end of the twentieth century. -

Prosecuting Rape Under the Statute of the War Crimes Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia Sharon A

Brooklyn Journal of International Law Volume 21 | Issue 2 Article 2 12-1-1995 Prosecuting Rape Under the Statute of the War Crimes Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia Sharon A. Healey Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil Recommended Citation Sharon A. Healey, Prosecuting Rape Under the Statute of the War Crimes Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, 21 Brook. J. Int'l L. 327 (1995). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil/vol21/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. Prosecuting Rape Under the Statute of the War Crimes Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia By Sharon A. Healey* I. INTRODUCTION From the relative safety of a one room cabin in a refugee camp in Gasinci, Croatia, 15-year-old Emina Gasi recounted the horrors of February 1994, when men in Serbian military uniforms, stockings over their faces, broke into her home in Banja Luka, slashed her grandfather's head and arms with knives, killing him, and, as he lay dying, raped her.' Her story is not unique. As war in the former Yugoslavia rages on, refu- gees have poured out wrenching accounts of systematic rapes and sexual abuses, mostly at the hands of Serbian forces.2 These stories include: repeated rapes of girls as young as 6 and 7; violations by neighbors and strangers alike; gang rapes so brutal their victims die; rape camps where Serbs routinely abused and murdered Muslim and Croat women; rapes of young girls performed in front of fathers, mothers, siblings and children; rapes committed explicitly to impregnate Muslim women and hold them captive until they give birth to unwanted Serbian babies.3 * LL.M.