17 / /L~9 /I7 - R;,)E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Success of the Light Armoured Vehicle

Canadian Military History Volume 20 Issue 2 Article 4 2011 The Success of the Light Armoured Vehicle Frank Maas Wilfrid Laurier University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Recommended Citation Maas, Frank "The Success of the Light Armoured Vehicle." Canadian Military History 20, 2 (2011) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maas: Light Armoured Vehicle The Success of the Light Armoured Vehicle Frank Maas he seeds for Canada’s purchase Cadillac-Gage, but the owner of of the Light Armoured Vehicle Abstract: Since the 1970s, budget Swiss firm MOWAG, Walter Ruf, T constraints and debates over the (LAV) lie as far back as 1964, when tank’s relevance have prompted came to the Department of National the Defence White Paper called for the Canadian Forces (CF) to pursue Defence (DND) in Ottawa to present the creation of a force equipped with lighter, cheaper, and more flexible his company’s new vehicle design, a flexible, light, and air-transportable vehicles. The Light Armoured Vehicle the “Piranha.”7 DND indicated that vehicle to serve in UN missions. This (LAV), built in London, Ontario, has the vehicle must be built in Canada to been purchased in great numbers resulted in a confused reaction that to satisfy these demands, and it have a chance of winning the bid, and saw the Canadian Forces (CF) looking has largely succeeded. -

Heroics & Ros Index

MBW - ARMOURED RAIL CAR Page 6 Error! Reference source not found. Page 3 HEROICS & ROS WINTER 2009 CATALOGUE Napoleonic American Civil War Page 11 Page 12 INDEX Land , Naval & Aerial Wargames Rules 1 Books 1 Trafalgar 1/300 transfers 1 HEROICS & ROS 1/300TH SCALE W.W.1 Aircraft 1 W.W.1 Figures and Vehicles 4 W.W.2 Aircraft 2 W.W.2. Tanks &Figures 4 W.W.2 Trains 6 Attack & Landing Craft 6 SAMURAI Page11 Modern Aircraft 3 Modern Tanks & Figures 7 NEW KINGDOM EGYPTIANS, Napoleonic, Ancient Figures 11 HITTITES AND Dark Ages, Medieval, Wars of the Roses, SEA PEOPLES Renaissance, Samurai, Marlburian, Page 11 English Civil War, Seven Years War, A.C.W, Franco-Prussian War and Colonial Figures 12 th Revo 1/300 full colour Flags 12 VIJAYANTA MBT Page 7 SWA103 SAAB J 21 Page 4 World War 2 Page 4 PRICE Mk 1 MOTHER Page 4 £1.00 Heroics and Ros 3, CASTLE WAY, FELTHAM, MIDDLESEX TW13 7NW www.heroicsandros.co.uk Welcome to the new home of Heroics and Ros models. Over the next few weeks we will be aiming to consolidate our position using the familiar listings and web site. However, during 2010 we will be bringing forward some exciting new developments both in the form of our web site and a modest expansion in our range of 1/300 scale vehicles. For those wargamers who have in the past purchased their Heroics and Ros models along with their Navwar 1/300 ships, and Naismith and Roundway 15mm figures, these ranges are of course still available direct from Navwar www.navwar.co.uk as before, though they will no longer be carrying the Heroics range. -

Msm Land System Division

LAND SYSTEM MSM DIVISION DEFENCE TECHNICS: DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT | PRODUCTION | SPARE PARTS | SERVICE & MAINTENANCE | MODERNIZATION ABOUT US MSM GROUP MSM GROUP Ltd. was established in 2015 by transformation of MSM Martin Ltd., which dealt with The resources and competencies: construction, development, production and sales mainly with military material. MSM Martin Ltd. was 1. Development of the product and the production process included complete documentation founded in 2004 on the base of MSM Ltd. In next years the MSM Martin Ltd. took over several military 2. Engineering construction of product including the prototype production and the pre-serial testing companies located in the middle of Slovakia, and built on its traditional manufacturing activities in 3. Production line, tools and jigs engineering construction, and production military and civil production. 4. Production of various types of small, middle and large caliber ammunition and associated charges, Due to ZVS company inclusion into the group structure we can state that the origin of MSM GROUP fuses and primers for guns and cannons. Deliveries with all of necessary documentation, and Ltd. comes back to 1927 when then Škoda Works in Plzeň, as a monopoly producer of ammunition certificates technics decided to build so called „spare factory“ in Slovakia. The company was totally destroyed 5. Services during the ammo life cycle: Testing, Revision, Modernization, Life cycle prolongation, during the World War II, and it took several years while the production was restored to such extend, Disassembly, Ecological disposal that its products were supplied not only for the Ministry of National Defense, but for many countries 6. In the case also the production line development, production and the transfer with whole necessary worldwide as well. -

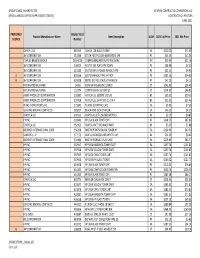

Staples June 2021 Revised.Pdf

GROUP 23000, AWARD 22790 STAPLES CONTRACT & COMMERCIAL LLC MISCELLANEOUS OFFICE SUPPLIES (STATEWIDE) CONTRACT NO.: PC67296 JUNE 2021 PREFERRED Staples Stock Product Manufacturer Name Item Description UOM 2021 List Price 2021 Net Price SOURCE Number CANON USA 887359 CANON 128 BLACK TONER EA $120.00 $71.69 3M CORPORATION 513246 SCTCH PKGTP LGDIS 48MMX50M 4PK PK $43.39 $11.53 STAPLES BRANDS GROUP 24394010 COMPOSTBAGASSEPLATE 9IN 250PK PK $59.99 $22.18 3M CORPORATION 504023 POST IT 3X3 POP CAPE TOWN PK $28.98 $7.53 3M CORPORATION 211540 SCOTCH 6PK 3/4X650 MAGIC TAPE PK $22.31 $4.91 D 3M CORPORATION 809556 SCOTCH MAGIC TAPE 24 PACK PK $102.26 $14.83 B 3M CORPORATION 609828 NOTES 3X3 YELLOW/ULTRA/NEON PK $47.23 $4.16 INTERNATIONAL PAPER 14336 FORE MP PREM 8.5X11/5000 CT $246.56 $26.45 INTERNATIONAL PAPER 122374 COPYPLUS 8.5X11 COPY CS CT $274.32 $46.91 AVERY PRODUCTS CORPORATION 209882 AVY LSR LBL 3000PK 1X2 5/8 BX $53.35 $10.55 AVERY PRODUCTS CORPORATION 209908 AVY LSR LBL 14UP 100‐1 1/3 X 4 BX $53.35 $13.45 TEXAS INSTRUMENTS INC. 275842 TI‐30XA SCIENTIFIC CALC EA $9.99 $7.55 GENERAL BINDING CORP ACCO 285007 BLACK #646 DESK STAPLER EA $46.52 $4.26 CRAYOLA LLC 300525 CRAYOLA 12CT COLORED PENCILS BX $3.20 $0.89 HP INC. 332849 HP 05A BLACK TONER 2PK PK $244.23 $87.06 CRAYOLA LLC 352369 CRAYOLA 8CT BRD WASH MKR BX $5.33 $1.88 BROTHER INTERNATIONAL CORP. 356338 BROTHER TN750 BLACK TONER HY EA $124.99 $49.50 SANFORD, L.P. -

Foreign Military Studies Office

HTTPS://COMMUNITY.APAN.ORG/WG/TRADOC-G2/FMSO/ Foreign Military Studies Office Volume 10 Issue #6 OEWATCH June 2020 FOREIGN NEWS & PERSPECTIVES OF THE OPERATIONAL ENVIRONMENT EURASIA 31 Chinese Information on COVID-19 in the PLA 62 Communications to Counter Extremism in the Lake Chad Basin 3 No Hunter at the Victory Day Parade 32 China: Elevating the Status and Role of the People’s Armed 63 Somalia: Ethiopia’s Influence Rises as Kenya Prepares to Leave 4 Alternate Medical Service for Russian Draftees Police Force AMISOM 5 Inside Russia: Spreading Virus Disinformation Narratives 33 A Look at the PLA’s Combat Medical Capabilities 64 Al-Shabaab in Somalia Turns to Criminal Activities in Kenya for 6 Faith and Russian Military Victory 35 China’s COVID-19 “Letter Diplomacy” Funding 8 Chinese Help to Restore the Kuznetsov 37 Chinese Views of Public Opinion Warfare 65 Al-Shabaab Kidnaps Professionals to Utilize Their Skills 9 Toward a “System of Regional Security in the Arctic”: A 39 China’s COVID-19 Information Campaign is Backfiring in Europe 66 The Impact of COVID-19 on African Security Russian Perspective 41 Philippine Insurgents Disrupt Army’s COVID-19 Response 67 Mali Struggles to Fight Pandemic 10 Looking Beyond China: Asian Actors in the Russian Arctic 42 Coronavirus Shutdown Complicates Southern Thailand Conflict 69 The EU Suspends Training Mission in Mali due to COVID-19 (Part One) 43 The Focus of Pakistan’s 2020 Green Book 70 Chad Considers Withdrawing from Regional Military 12 Russian Airborne Troops Conduct High Altitude Arctic Cooperation -

General Assembly Distr.: General 12 July 2011 English Original: Arabic/English/French/ Russian/Spanish

United Nations A/66/127 General Assembly Distr.: General 12 July 2011 English Original: Arabic/English/French/ Russian/Spanish Sixty-sixth session Item 99 (g) of the preliminary list* General and complete disarmament: transparency in armaments United Nations Register of Conventional Arms Report of the Secretary-General Summary The present report, which is submitted pursuant to General Assembly resolution 64/54, contains information received from Member States on the export and import of conventional arms covered by the United Nations Register of Conventional Arms, including “nil” reports, as well as additional background information on military holdings, procurement through national production and international transfers of small arms and light weapons for the calendar year 2010. As of the date of the present report, the Secretary-General has received reports from 64 Governments. * A/66/50. 11-41131 (E) 190711 080911 *1141131* A/66/127 Contents Page I. Introduction ................................................................... 3 II. Information received from Governments............................................ 3 A. Index of information submitted by Governments................................. 4 B. Reports received from Governments on conventional arms transfers................. 6 III. Information received from Governments on military holdings and procurement through national production ............................................................. 41 IV. Information received from Governments on international transfers of small -

Poland Historical AFV Register

Poland Historical AFV Register Armoured Fighting Vehicles Preserved in Poland V2.2 10 January 2010 Łukasz Sambor For http://www.militarnepodroze.net/ and the AFV Association Source: http://www.wp.mil.pl (Polish Ministry of National Defense copyright) 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................3 DOLNOŚLĄSKIE.....................................................................................................4 KUJAWSKO-POMORSKIE........................................................................................5 LUBELSKIE............................................................................................................6 LUBUSKIE.............................................................................................................7 ŁÓDZKIE...............................................................................................................9 MAZOWIECKIE......................................................................................................10 Polish Army Museum...................................................................................11 MAŁOPOLSKIE.......................................................................................................15 OPOLSKIE.............................................................................................................16 PODLASKIE...........................................................................................................17 PODKARPACKIE....................................................................................................18 -

Chinese Armed Forces Order of Battle (Orbat)

CHINESE ARMED FORCES ORDER OF BATTLE (ORBAT) CHINESE ARMED FORCES ORDER OF BATTLE (ORBAT) 1 Composition of Group Army : - 4 Composition of Heavy Combined Arms Brigade : - 4 Composition of Light Combined Arms Brigade 5 Composition of Mechanised Infantry Brigade 5 Composition of Independent Artillery Brigade 5 Composition of Independent Air Defence Brigade 5 Composition of Infantry Squads. 5 Battalion Command 7 Brigades 7 THEATER COMMANDS 8 WESTERN THEATER COMMAND Guangzhou, Guangdong 8 76th Group Army, Xining, Qinghai Province (Former 21st Group Army) 8 77th Group Army, Changzhou City, Sichuan. (Former 13th Group Army) 9 4th Motorised Infantry Division, Xinjiang MD 10 6th Highland Mechanised Infantry Division, Depsang 10 8th Motorised Infantry Division, Xinjiang MD 10 11th Motorised Infantry Division, Xinjiang MD 11 No naval fleet 11 Air Assets 11 Air Bases 11 TIBET MILITARY DISTRICT 11 15th Airborne Corps 11 52nd Mountain Motorised Infantry Brigade, Nyingchi (4600 troops) 12 53rd Mountain Motorised Infantry Brigade, Lhasa/Nyingchi? (4600 troops) 12 54th Mechanised Infantry Brigade, Lhasa (3000 troops) 12 308th Artillery Brigade (3000 troops) 13 Independent Battalions ?? 13 SOUTHERN THEATER COMMAND. Guangzhou, Guangdong 13 74th Group Army (Former 41st Group Army) 13 75th Group Army (Former 42nd Group Army) 14 South Sea Fleet (Naval) 14 Air Assets 15 Air Bases 16 CENTRAL THEATER COMMAND. Beijing 16 1 81st Group Army (Former 65th Group Army) 16 82nd Group Army (Former 38th Group Army) 17 83rd Group Army (Former 54th Group Army) 17 No naval fleet 17 Air Assets 17 Air Bases 18 NORTHERN THEATER COMMAND. Shenyang, Liaoning 18 78th Group Army (Former 16th Group Army) 18 79th Group Army (Former 39th Group Army) 18 80th Group Army (Former 26th Group Army) 18 North Sea Fleet 18 Air Bases 19 Air Assets 19 EASTERN THEATER COMMAND. -

ARMORED VEHICLES MARKET REPORT 2019 the WORLD’S LARGEST DEDICATED ARMOURED VEHICLE CONFERENCE #Iavevent

presents THE WORLD’S LARGEST DEDICATED ARMOURED VEHICLE CONFERENCE @IAVehicles ARMORED VEHICLES MARKET REPORT 2019 THE WORLD’S LARGEST DEDICATED ARMOURED VEHICLE CONFERENCE #IAVEvent CONTENTS Rationale 3 Regional Developments 4 Africa 5 Europe 7 Indo-Asia Pacific 11 Middle East 14 North America 17 Latin America 18 Global Armoured Vehicle Holdings 19 Europe 20 Russia and Central Asia 24 Asia 27 North America 31 Middle East and North Africa 32 Sub-Saharan Africa 36 Latin America and Caribbean 41 International Armoured Vehicles 2019 44 2 THE WORLD’S LARGEST DEDICATED ARMOURED VEHICLE CONFERENCE #IAVEvent INTRODUCTION Within an ever changing strategic context, the market for armoured vehicles and related equipment has become even more wide- ranging. There has been a significant rise in the use of UGVs, artificial intelligence, virtual training and survivability equipment. Also, Active Protection Systems (APS) are being developed in lighter, cheaper and more accurate forms, supporting their case as a popular solution for the future battlespace. With all of the aforementioned in mind, the deployment of MBTs is still seen as a necessity by most in spite of climbing demand for light protected mobility. Ahead of International Armoured Vehicles 2019 conference, Defence IQ has compiled this market report to outline global key programmes and future requirements across all types of armoured vehicles. In January, Senior Representatives from the below countries will share their current requirements and challenges with the audience made up of over -

National Competent Authorities' Approval Certificates for Package Design, Special Form Material and Shipment of Radioactive Material

IAEA-TECDOC-1171 Directory of national competent authorities' approval certificates for package design, special form material and shipment of radioactive material 2000 Edition INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY UZr August 2000 e IAETh A doe t normallno s y maintain stock f reporto s n thii s s series. The e howevear y r collected by the International Nuclear Information System (INIS) as non-conventional literature. Shoul f printo a documend t a cop, ou n microfich o ye b t n electronii r o e c e b forma n ca t purchased fro INIe mth S Document Delivery Services: INIS Clearinghouse International Atomic Energy Agency Wagramer Strasse5 0 10 P.Ox Bo . A-1400 Vienna, Austria Telephone: (43 260)1 0 2288 2286r 0o 6 Fax: (43) 1 2600 29882 E-mail: [email protected] Orders should be accompanied by prepayment of 100 Austrian Schillings in the form of a cheque or credit card (VISA, Mastercard). More informatio e INIth S n o nDocumen t Delivery Service a lisf nationa o td an s l document delivery services where these report alsn ordere sitINIb e e founse ca ot b e th b a S We n n do dca http://www.iaea.org/inis/dd srv.htm. IAEA SAFETY RELATED PUBLICATIONS IAEA SAFETY STANDARDS Under the terms of Article III of its Statute, the IAEA is authorized to establish standards of safety for protection against ionizing radiation and to provide for the application of these standards to peaceful nuclear activities. e regulatorTh y related publication y meanb s f whico s e IAEth h A establishes safety standard measured an s e issueIAEe ar th s n Adi Safety Standards Series. -

Package Design, Special Form Material Shipmentand Radioactiveof Material 1997 Edition

XA9745163 IAEA-TECDOC-956 Directory of national competent authorities' approval certificatesfor package design, special form material shipmentand radioactiveof material 1997 Edition INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY The originating Section of this publication in the IAEA was: Radiation Safety Section International Atomic Energy Agency Wagramerstrasse5 P.O. Box 100 A-1400 Vienna, Austria DIRECTOR NATIONAF YO L COMPETENT AUTHORITIES' APPROVAL CERTIFICATES FOR PACKAGE DESIGN, SPECIAL FORM MATERIAL AND SHIPMEN RADIOACTIVF TO E MATERIAL 1997 EDITION IAEA, VIENNA, 1997 IAEA-TECDOC-956 ISSN 1011-4289 ©IAEA, 1997 Printed by the IAEA in Austria August 1997 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................... 7 TABLE 1. CURRENT CERTIFICATES................................................................................................. 9 TABLE 2. EXPIRED CERTIFICATES.................................................................................................. 23 TABL . ECURREN3 T CERTIFICATE VALIDATIOY SB N NUMBER ..................................................7 .2 TABLE 4. EXPIRED CERTIFICATES BY VALIDATION NUMBER ..................................................... 35 TABL . EMASS5 , CONTENT DESCRIPTIOD SAN CERTIFICATEL AL R NFO S AND VALIDATIONS............................................................................................................ 39 TABLE 6. CERTIFICATES LISTED BY MEMBER STATE................................................................. -

Armoured Vehicles Market Report 2014 FOREWORD

Defence IQ ARMOURED VEHICLES MARKET REPORT 2014 FOREWORD In 1914, the British War Office placed an order for a Holt tractor – one of the most famous forebears of the military battle tank – and began trials at Aldershot in the hopes of delivering a solution to the stalemate of trench warfare through the use of an armoured ‘land ship’. One hundred years on and Aldershot will again be host to the world’s largest conference dedicated to armoured vehicles, the very descendants of that Holt tractor. Modern armoured vehicles will take to the Long Valley Test Track as part of the International Armoured Vehicles 2014 exhibition and conference. Ahead of this key event, Defence IQ has published this report to provide a broad overview of how the international industry looks today. Two overriding trends struck me while reading this report: First, there is a discernible shift – a far more palpable one than I’ve seen in previous iterations of this annual report – of armoured vehicle demand in the growing economies of the Middle East, Africa and Latin America while the more established markets of North America and Europe suffer the effects of the economic downturn. And second, it is clear that, despite protestations to the contrary over recent years, the era of the tank is certainly not dead. While new technologies and ‘smart’ platforms continue to roll off the production line, the survey data and analysis in this report demonstrate that there will always be a requirement for armoured vehicles, be it for expeditionary missions or peacekeeping operations. Despite the tough economic context, nations continue to spend considerable sums on maintaining capable armoured and protected mobility forces.