The South East of Malta and Its Defence up to 1614

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOCAL NOTICE to MARINERS No 105 of 2019

PORTS AND YACHTING DIRECTORATE LOCAL NOTICE TO MARINERS No 105 of 2019 Our Ref: TM/PYD/132/89 19 August 2019 Filming outside Marsamxett Harbour and inside the Grand harbour, Valletta - The story of my wife The Ports and Yachting Directorate, Transport Malta notifies mariners and operators of vessels, that filming activities will take place outside Marsamxett Harbour at point A (as indicated on attached chart) and at Boiler Wharf inside the Grand Harbour, Valletta. The filming will take place on Friday 23 rd August 2019 and Saturday 24 th August 2019. The filming involves the use of the vessel UTEC Surveyor as a prop and she will be towed by the tug boats Sea Wolf and Sea Jaguar whenever it has to be moved. Friday 23 rd August 2019: 0600 hours UTEC Surveyor will be towed from Cassar Shipyard to be moored at Boiler Wharf. 0900 hours UTEC Surveyor towed from Boiler Wharf to outside Marsamxett Harbour where filming onboard the vessel will commence. In the afternoon the UTEC Surveyor will be towed again to Boiler Wharf where filming will take place from arrival to midnight. Saturday 24 th August 2019: 0900 hours UTEC Surveyor towed from Boiler Wharf to outside Marsamxett Harbour where filming onboard the vessel will commence. In the afternoon the UTEC Surveyor will be towed again to Boiler Wharf where filming will take place from arrival to midnight. Monday 26 th August 2019: In the afternoon the UTEC Surveyor will be towed back to Cassar Shipyard. Mariners are to note the above and give a wide berth while the UTEC Surveyor is being towed and while it is anchored at point A (as indicated on attached chart). -

Residential Property Transactions: April 2021

11 May 2021 | 1100 hrs | 087/2021 The number of fi nal deeds of sale relating to residential property during April 2021 amounted to 1,130, an increase of 540 deeds when compared to those registered a year earlier. In April 2021, 1,430 promise of sale agreements relating to residential property were registered, an increase of 1,161 agreements over the same period last year. Residential Property Transactions: April 2021 Cut-off date: Final Deeds of Sale 4 May 2021 In April 2021, the number of fi nal deeds of sale relating to residential property amounted to 1,130, an increase of 540 deeds when compared to those registered a year earlier (Table 1). The value of these deeds totalled €228.4 million, 91.6 per cent higher than the corresponding value recorded in April 2020 (Table 2). With regard to the region the property is situated in, the highest numbers of fi nal deeds of sale were recorded in the two regions of Mellieħa and St Paul’s Bay, and Ħaż-Żabbar, Xgħajra, Żejtun, Birżebbuġa, Marsaskala and Marsaxlokk, at 150 and 143 respectively. The lowest numbers of deeds were noted in the region of Cottonera, and the region of Mdina, Ħad-Dingli, Rabat, Mtarfa and Mġarr. In these regions, 13 and 32 deeds respectively were recorded (Table 3). Chart 1. Registered fi nal deeds of sale - monthly QXPEHURIUJLVWHUHGILQDOGHHGV - )0$0- - $621' - )0$0- - $621' - )0$ SHULRG Compiled by: Price Statistics Unit Contact us: National Statistics Offi ce, Lascaris, Valletta VLT 2000 1 T. +356 25997219, E. [email protected] https://twitter.com/NSOMALTA/ https://www.facebook.com/nsomalta/ Promise of Sale Agreements In April 2021, 1,430 promise of sale agreements relating to residential property were registered, an increase of 1,161 agreements over the same period last year (Table 4). -

Introduction – Grand Harbour Marina

introduction – grand harbour marina Grand Harbour Marina offers a stunning base in historic Vittoriosa, Today, the harbour is just as sought-after by some of the finest yachts Malta, at the very heart of the Mediterranean. The marina lies on in the world. Superbly serviced, well sheltered and with spectacular the east coast of Malta within one of the largest natural harbours in views of the historic three cities and the capital, Grand Harbour is the world. It is favourably sheltered with deep water and immediate a perfect location in the middle of the Mediterranean. access to the waterfront, restaurants, bars and casino. With berths for yachts up to 100m (325ft) in length, the marina offers The site of the marina has an illustrious past. It was originally used all the world-class facilities you would expect from a company with by the Knights of St John, who arrived in Malta in 1530 after being the maritime heritage of Camper & Nicholsons. exiled by the Ottomans from their home in Rhodes. The Galley’s The waters around the island are perfect for a wide range of activities, Creek, as it was then known, was used by the Knights as a safe including yacht cruising and racing, water-skiing, scuba diving and haven for their fleet of galleons. sports-fishing. Ashore, amid an environment of outstanding natural In the 1800s this same harbour was re-named Dockyard Creek by the beauty, Malta offers a cosmopolitan selection of first-class hotels, British Colonial Government and was subsequently used as the home restaurants, bars and spas, as well as sports pursuits such as port of the British Mediterranean Fleet. -

22Nd July 2021 Hon. Dr Clayton Bartolo Minister for Tourism And

22nd July 2021 Hon. Dr Clayton Bartolo Minister for Tourism and Consumer Protection RE: Malta Tourism Authority (MTA) Design Contest for Marsaskala As concerned citizens of Marsaskala we feel the need to write this letter to ensure that our worries about the ‘regeneration’ of our locality are taken into consideration. We feel we are being left in the dark regarding the many plans and developments in store for many parts of Marsaskala. We would not like to see these changes take place as we believe they will not benefit the residents and will not serve to attract more tourists to our village. In particular, we have strong reason to believe that the recently launched Malta Tourism Authority (MTA) Design Contest for Marsaskala was simply put in place to further certain business interests with complete disregard of the whole population at large. Almost a year ago, the mayor announced a sub-committee for the regeneration of Marsaskala. The people forming this sub-committee were chosen by the mayor himself, and for over two years, had been meeting and working on a variety of proposals for Marsaskala behind closed doors and in liaison with Infrastructure Malta and the MTA. This sub-committee was chaired by Mr Ray Abela. Other members included his cousin, Mr Eric Abela, with business interests in the Marsaskala square and surroundings, Mr Joseph Farrell, also with business interests in the Marsaskala square, Ms Angele Abela, head of a Minister’s secretariat, and the mayor himself. Angele Abela and Joseph Farrell left the sub-committee soon after its creation. -

Every Life in 19Th and Early 20Th Century Malta

MALTESE HISTORY Unit L Everyday Life and Living Standards Public Health Form 4 1 Unit L.1 – Population, Emigration and Living Standards 1. Demographic growth The population was about 100,000 in 1800, it surpassed the 250,000 mark after World War II and rose to over 300,000 by 1960. A quarter of the population lived in the harbour towns by 1921. This increase in the population caused the fast growth of harbour suburbs and the rural villages. The British were in constant need of skilled labourers for the Dockyard. From 1871 onwards, the younger generation migrated from the villages in search of employment with the Colonial Government. Employment with the British Services reached a peak in the inter-war period (1919-39) and started to decline after World War II. In the 1950s and 1960s the British started a gradual rundown of military personnel in their overseas colonies, including Malta. Before the beginning of the first rundown in 1957, the British Government still employed 27% of the Maltese work force. 2. Maltese emigration The Maltese first became attracted to emigration in the early 19th century. The first organised attempt to establish a Maltese colony of migrants in Corfu took place in 1826. Other successful colonies of Maltese migrants were established in North African and Mediterranean ports in Algiers, Tunis, Bona, Tripoli, Alexandria, Port Said, Cairo, Smyrna, Constantinople, Marseilles and Gibraltar. By 1842 there were 20,000 Maltese emigrants in Mediterranean countries (15% of the population). But most of these returned to Malta sometime or another. Emigration to Mediterranean areas declined rapidly after World War II. -

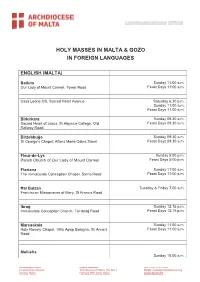

Holy Masses in Malta & Gozo in Foreign Languages

HOLY MASSES IN MALTA & GOZO IN FOREIGN LANGUAGES ENGLISH (MALTA) Balluta Sunday 11:00 a.m. Our Lady of Mount Carmel, Tower Road Feast Days 11:00 a.m. Casa Leone XIII, Sacred Heart Avenue Saturday 6:30 p.m. Sunday 11:00 a.m. Feast Days 11:00 a.m. Birkirkara Sunday 09:30 a.m. Sacred Heart of Jesus, St Aloysius College, Old Feast Days 09:30 a.m. Railway Road Birżebbuġa Sunday 09:30 a.m. St George’s Chapel, Alfons Maria Galea Street Feast Days 09:30 a.m. Fleur-de-Lys Sunday 5:00 p.m. Parish Church of Our Lady of Mount Carmel Feast Days 5:00 p.m. Floriana Sunday 11:00 a.m. The Immaculate Conception Chapel, Sarria Road Feast Days 11:00 a.m. Ħal Balzan Tuesday & Friday 7:00 a.m. Franciscan Missionaries of Mary, St Francis Road Ibraġ Sunday 12:15 p.m. Immaculate Conception Church, Tal-Ibraġ Road Feast Days 12:15 p.m. Marsaskala Sunday 11:00 a.m. Holy Rosary Chapel, Villa Apap Bologna, St Anne’s Feast Days 11:00 a.m. Road Mellieħa Sunday 10:00 a.m. Shrine of Our Lady, Pope’s Visit Square Feast Days 10:00 a.m. Msida Sunday 10:00 a.m. Dar Manwel Magri, Mgr Carmelo Zammit Street Naxxar Sunday 11:30 a.m. Church of Divine Mercy, San Pawl tat-Tarġa Feast Days 11:30 a.m. The Risen Christ Chapel, Hilltop Gardens Sunday 11:30 a.m. Retirement Village, Inkwina Road Paceville Sunday 11:30 a.m. -

Census of Population and Housing 2011

CENSUS OF POPULATION AND HOUSING 2011 Preliminary Report National Statistics Office, Malta, 2012 Published by the National Statistics Office Lascaris Valletta Malta Tel.: (+356) 25 99 70 00 Fax: (+356) 25 99 72 05 e-mail: [email protected] website: http://www.nso.gov.mt CIP Data Census of Population and Housing 2011, Preliminary Report. - Valletta: National Statistics Office, 2012 xxx, 53p. ISBN: 978-99957-29-35-6 For further information, please contact: Research and Methodology Unit National Statistics Office Lascaris Valletta VLT 2000 Malta Tel: (+356) 25 99 78 29 Our publications are available from: The Data Shop National Statistics Office Lascaris Valletta VLT 2000 Tel.: (+356) 25 99 72 19 Fax: (+356) 25 99 72 05 Printed at the Government Printing Press CONTENTS Page FOREWORD v 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Legal background ix 1.2 Participation in the Census ix 1.3 Confidentiality ix 1.4 Information Campaign ix 1.5 Operation x 1.5.1 Project Management x 1.5.2 Operations Centre x 1.5.3 The Census Questionnaire x 1.5.4 Operations x 1.5.5 Briefing Sessions xi 1.5.6 Enumeration Areas xi 1.5.7 Field Work xii 1.5.8 Keying-In of Data xiii 1.6 Post-Enumeration xiii 1.6.1 Follow-up exercise xiii 1.6.2 Final Report xiii 1.6.3 Accuracy of Preliminary Findings xiii 2. COMMENTARY 2.1 Population growth along the years xvii 2.2 Geographical distribution xviii 2.3 Population by living quarters xx 2.4 Population density xx 2.5 Gender distribution xxi 2.6 Age distribution xxii 2.7 Distribution by nationality xxiii 3. -

Gazzetta Tal-Gvern Ta' Malta

Nru./No. 20,404 Prezz/Price €1.98 Gazzetta tal-Gvern ta’ Malta The Malta Government Gazette L-Erbgħa, 13 ta’ Mejju, 2020 Pubblikata b’Awtorità Wednesday, 13th May, 2020 Published by Authority SOMMARJU — SUMMARY Avviżi tal-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar ....................................................................................... 3853 - 3892 Planning Authority Notices .............................................................................................. 3853 - 3892 It-13 ta’ Mejju, 2020 3853 PROĊESS SĦIĦ FULL PROCESS Applikazzjonijiet għal Żvilupp Sħiħ Full Development Applications Din hija lista sħiħa ta’ applikazzjonijiet li waslu għand This is a list of complete applications received by the l-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar. L-applikazzjonijiet huma mqassmin Planning Authority. The applications are set out by locality. bil-lokalità. Rappreżentazzjonijiet fuq dawn l-applikazzjonijiet Any representations on these applications should be sent in għandhom isiru bil-miktub u jintbagħtu fl-uffiċini tal-Awtorità writing and received at the Planning Authority offices or tal-Ippjanar jew fl-indirizz elettroniku ([email protected]. through e-mail address ([email protected]) within mt) fil-perjodu ta’ żmien speċifikat hawn taħt, u għandu the period specified below, quoting the reference number. jiġi kkwotat in-numru ta’ referenza. Rappreżentazzjonijiet Representations may also be submitted anonymously. jistgħu jkunu sottomessi anonimament. Is-sottomissjonijiet kollha lill-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar, All submissions to the Planning Authority, -

The Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of St. John of Jerusalem of Rhodes and of Malta – a General History of the Order of Malta

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OAR@UM Emanuel Buttigieg THE SOVEREIGN MILITARY HOSPITALLER ORDER OF ST. JOHN OF JERUSALEM OF RHODES AND OF MALTA – A GENERAL HISTORY OF THE ORDER OF MALTA INTRODUCTION: HOSPITALLERS Following thirteen years of excavation by the Israel Antiquities Authority, a thousand-year-old structure – once a hospital in Jerusalem – will be open to the public; part of it seems earmarked to serve as a restaurant. 1 In Syria, as the civil war rages on, reports and footage have been emerging of explosions in and around Crac des Chevaliers castle, a UNESCO World Heritage site. 2 During the interwar period (1923–1943), the Italian colonial authorities in the Dodecanese engaged in a wide-ranging series of projects to restore – and in some instances redesign – several buildings on Rhodes, in an attempt to recreate the late medieval/Renaissance lore of the island. 3 Between 2008 and 2013, the European Regional Development Fund provided the financial support necessary for Malta to undertake a large-scale restoration of several kilometres of fortifications, with the aim of not only preserving these structures but also enhancing Malta’s economic and social well- -being.4 Since 1999, the Sainte Fleur Pavilion in the Antananarivo University Hospital Centre in Madagascar has been helping mothers to give birth safely and assisting infants through care and research. 5 What binds together these seemingly disparate, geographically-scattered buildings, all with their stories of hope and despair? All of them – a hospital in Jerusalem, a castle in Syria, structures on Rhodes, fortifications on Malta, and yet another hospital, this time in Madagascar – attest to the constant (but evolving) mission of the Order of Malta “to Serve the Poor and Defend the Faith” over several centuries. -

Annual Report 2017 Contents

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 CONTENTS 3 4 9 CEO Water Water Report Resources Quality 14 20 32 Compliance Network Corporate Infrastructure Services Directorate 38 45 48 Strategic Human Unaudited Information Resources Financial Directorate Statement 2017 ANNUAL REPORT CEO REPORT CEO Report 2017 was a busy year for the Water Services quality across Malta. Secondly, RO plants will be Corporation, during which it worked hard to become upgraded to further improve energy efficiency and more efficient without compromising the high quality production capacity. Furthermore, a new RO plant service we offer our customers. will be commissioned in Gozo. This RO will ensure self-sufficiency in water production for the whole During a year, in which the Corporation celebrated island of Gozo. The potable water supply network to its 25th anniversary, it proudly inaugurated the North remote areas near Siġġiewi, Qrendi and Haż-Żebbuġ Wastewater Treatment Polishing Plant in Mellieħa. will be extended. Moreover, ground water galleries This is allowing farmers in the Northern region to will also be upgraded to prevent saline intrusion. benefit from highly polished water, also known as The project also includes the extension of the sewer ‘New Water’. network to remote areas that are currently not WSC also had the opportunity to establish a number connected to the network. Areas with performance of key performance indicator dashboards, produced issues will also be addressed. inhouse, to ensure guaranteed improvement. These Having only been recently appointed to lead the dashboards allow the Corporation to be more Water Services Corporation, I fully recognize that the efficient, both in terms of performance as well as privileges of running Malta’s water company come customer service. -

Regenerating the Valletta Grand Harbour Area Abstract

Restoring Life in the City: Regenerating the Valletta Grand Harbour Area Nadia Theuma(1), Anthony Theuma (2) (1)Institute of Tourism, Travel and Culture, University of Malta (2)Paragon Europe, Malta [email protected] Abstract Harbour Cities are formed by the economic, political, social and cultural activity that surrounds them. In recent years a number harbour cities worldwide have been at the forefront of regeneration – and re-building their reality based on revived cultural centres, new commercial activity and international links rather than basing their success on the industrial activity synonymous with their past lives. Valletta, Malta’s harbour – city region is one such city. This paper traces the fate of the Grand Harbour and its neighbouring cities in the island of Malta through the events of past centuries and the most recent regeneration projects. This paper will highlight the importance that harbours have for the prosperity of the urban areas. By analysing the rise and fall of the city regions, this paper will also demonstrate that regeneration of harbour areas has to be in line with the regeneration of the surrounding cities – one does not occur without another. The findings of this paper are based on research conducted in the area during the past eight years through three EU funded projects.1 Key Words: grand harbour, cities, socio-economic development, DevelopMed, DELTA, Malta 1 The Projects are: (1) DevelopMed – Interreg Project (a project commenced in 2009 run by the Marche Region, Italy with Paragon Europe, representing -

Summer Schedules

ISLA/VALLETTA 1 Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday Route 1 - Schedule Times Route 1 - Schedule Times Route 1 - Schedule Times 05:30-09:30 20 minutes 05:30-22:30 30 minutes 05:30-22:30 30 minutes 09:31-11:29 30 minutes 11:30-16:30 20 minutes 16:31-23:00 30 minutes BIRGU VENDA/VALLETTA 2 Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday Route 2 - Schedule Times Route 2 - Schedule Times Route 2- Schedule Times 05:15-20:25 20 minutes 05:30:00-22:45 30 minutes 05:30:00-22:45Isla/Birgu/Bormla/Valletta30 minutes 20:26-22:45 60 minutes KALKARA/VALLETTA 3 Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday Route 3 - Schedule Times Route 3 - Schedule Times Route 3 - Schedule Times 05:30 - 23:00 30 minutes 05:30 - 23:00 30 minutes 05:30Isla/Birgu/Bormla/Valletta - 23:00 30 minutes BIRGU CENTRE/VALLETTA 4 Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday Route 4 - Schedule Times Route 4 - Schedule Times Route 4 - Schedule Times 05:30:00 - 20:30 30 minutes 05:30-20:00 30 minutes 05:30-20:00 30 minutes 20:31 - 23:00 60 minutes 20:01-23:00 60 minutes 20:01-23:00 60 minutes BAHAR IC-CAGHAQ/VALLETTA 13 Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday Route 13 - Schedule Times Route 13 - Schedule Times Route 13 - Schedule Times 05:05 - 20:30 10 minutes 05:05 - 20:30 10 minutes 05:05 - 20:30 10 minutes 20:31 - 23:00 15 minutes 20:31 - 23:00 15 minutes 20:31 - 23:00 15 minutes PEMBROKE/VALLETTA 14 Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday Route 14 - Schedule Times Route 14 - Schedule Times Route 14 - Schedule Times 05:25 - 20:35 20 minutes 05:25 - 20:35 20 minutes 05:25 - 20:35 20 minutes 20:36 -22:48 30 minutes 20:36 -22:48 30 minutes