The Contribution of Tropical Secondary Forest Fragments to the Conservation of Fruit-Feeding Butterflies: Effects of Isolation and Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Check List of Butterflies of Rajshahi University Campus, Bangladesh Shah H.A

Univ. j. zool. Rajshahi. Univ. Vol. 32, 2013 pp. 27-37 ISSN 1023-6104 http://journals.sfu.ca/bd/index.php/UJZRU © Rajshahi University Zoological Society A Check List of Butterflies of Rajshahi University Campus, Bangladesh Shah H.A. Mahdi, A.M. Saleh Reza, Selina Parween* and A.R. Khan Department of Zoology, Rajshahi University, Rajshahi 6205, Bangladesh Abstract: The butterflies of the Rajshahi University campus have been collected and identifying since 1991. A total of 88 species under 56 genera and 10 families were identified. The number of identified species and their percentage were recorded family wise as: Nymphalidae (21, 23.86%), Pieridae (20, 22.73%), Papilionidae (13, 14.77%), Danaidae (10, 11.36%), Lycaenidae (9, 10.23%), Satyridae (8, 9.09%), Hespiriidae (4, 4.54%); and those of the families Acraeidae, Amathusidae and Riodinidae (1, 1.14%). There were 24 very common, 23 common, 25 rare and 16 very rare species. Key words: Butterfly, Rajshahi University campus. Introduction Information System) for the classification of the butterflies, which is a universally accepted Among the beautiful creatures, butterflies attract taxonomic framework for these insects. the attention of peoples of different age and status. These insects play an essential role as Butterflies inhabit various environmental pollinators and thus serve as a vital factor in fruit conditions (Robbins & Opler, 1997). The diversity and crop production. The eggs, caterpillars and and abundance of butterflies are rich in the adults of butterflies are also important links of the tropical areas, especially in the tropical food chain. Butterflies are important indicators of rainforests. Bangladesh with its humid tropical forest health and the healthiness of the climate and unique geographic location is environment. -

In Dong Van Karst Plateau, Ha Giang Province

SpeciesTAP list and CHI conservation SINH HOC priority2014, 36( of4 butterflies): 444-450 DOI: 10.15625/0866-7160/v36n4.6176 DOI: 10.15625/0866-7160.2014-X SPECIES LIST AND CONSERVATION PRIORITY OF BUTTERFLIES (Lepidoptera, Rhopalocera) IN DONG VAN KARST PLATEAU, HA GIANG PROVINCE Vu Van Lien Vietnam National Museum of Nature, VAST, [email protected] ABSTRACT: Study on species and conservation priority of butterflies in Dong Van Karst Plateau, Ha Giang province was carried out in forests of Lung Cu, Pho Bang, Ta Phin and sites near Dong Van town. The habitats are the natural forest on mountain, the secondary forest, the forest edge, shrub and grass from 1,400 to 1,700 m a.s.l. The study was carried out uncontinuously from May to September in 2008, 2010 and 2011. Total 132 species of 5 butterfly families were recorded during studied period. Two species listed in the Red Data Book of Vietnam and CITES are Troides aeacus and Teinopalpus imperialis. There are 33 species with individuals 1-2 (25% of all species), 44 species with individuals 3-5 (33% of all species), 14 species with individuals 6-10 (11% of all species), and 41 species with individuals more than 10 (31% of all species). Butterfly species of Dong Van karst plateau consists of 12.6% of all butterfly species of Vietnam, but the family Papilionidae of Dong Van karst plateau consists of 40% of all species of the family of Vietnam. The family Papilionidae is very important for conservation of insects. Some species distributed in Vietnam merely found in the studied area are Byasa hedistus, Papilio elwesi, Sasakia funeblis, S. -

The Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972 ______

THE WILD LIFE (PROTECTION) ACT, 1972 ____________ ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS ____________ CHAPTER I PRELIMINARY SECTIONS 1. Short title, extent and commencement. 2. Definitions. CHAPTER II AUTHORITIES TO BE APPOINTED OR CONSTITUTES UNDER THE ACT 3. Appointment of Director and other officers. 4. Appointment of Life Warden and other officers. 5. Power to delegate. 5A. Constitution of the National Board for Wild Life. 5B. Standing Committee of the National Board. 5C. Functions of the National Board. 6. Constitution of State Board for Wild Life. 7. Procedure to be followed by the Board. 8. Duties of State Board for Wild Life. CHAPTER III HUNTING OF WILD ANIMALS 9. Prohibition of hunting. 10. [Omitted.] 11. Hunting of wild animals to be permitted in certain cases. 12. Grant of permit for special purposes. 13. [Omitted.] 14. [Omitted.] 15. [Omitted.] 16. [Omitted.] 17. [Omitted.] CHAPTER IIIA PROTECTION OF SPECIFIED PLANTS 17A. Prohibition of picking, uprooting, etc. of specified plant. 17B. Grants of permit for special purposes. 17C. Cultivation of specified plants without licence prohibited. 17D. Dealing in specified plants without licence prohibited. 17E. Declaration of stock. 17F. Possession, etc., of plants by licensee. 17G. Purchase, etc., of specified plants. 1 SECTIONS 17H. Plants to be Government property. CHAPTER IV PROTECTED AREAS Sanctuaries 18. Declaration of sanctuary. 18A. Protection to sanctuaries. 18B. Appointment of Collectors. 19. Collector to determine rights. 20. Bar of accrual of rights. 21. Proclamation by Collector. 22. Inquiry by Collector. 23. Powers of Collector. 24. Acquisition of rights. 25. Acquisition proceedings. 25A. Time-limit for completion of acquisition proceedings. 26. Delegation of Collector’s powers. -

ZV-343 003-268 | Vane-Wright 04-01-2007 15:47 Page 3

ZV-343 003-268 | vane-wright 04-01-2007 15:47 Page 3 The butterflies of Sulawesi: annotated checklist for a critical island fauna1 R.I. Vane-Wright & R. de Jong With contributions from P.R. Ackery, A.C. Cassidy, J.N. Eliot, J.H. Goode, D. Peggie, R.L. Smiles, C.R. Smith and O. Yata. Vane-Wright, R.I. & R. de Jong. The butterflies of Sulawesi: annotated checklist for a critical island fauna. Zool. Verh. Leiden 343, 11.vii.2003: 3-267, figs 1-14, pls 1-16.— ISSN 0024-1652/ISBN 90-73239-87-7. R.I. Vane-Wright, Department of Entomology, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK; R. de Jong, Department of Entomology, National Museum of Natural History, PO Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands. Keywords: butterflies; skippers; Rhopalocera; Sulawesi; Wallace Line; distributions; biogeography; hostplants. All species and subspecies of butterflies recorded from Sulawesi and neighbouring islands (the Sulawesi Region) are listed. Notes are added on their general distribution and hostplants. References are given to key works dealing with particular genera or higher taxa, and to descriptions and illustrations of early stages. As a first step to help with identification, coloured pictures are given of exemplar adults of almost all genera. General information is given on geological and ecological features of the area. Combi- ned with the distributional information in the list and the little phylogenetic information available, ende- micity, links with surrounding areas and the evolution of the butterfly fauna are discussed. Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Sulawesi and its place in the Malay Archipelago ........................................................................... -

Schedules I to VI of Wildlife Protection Act, 1972

SCHEDULE I (Sections 2, 8,9,11, 40,41, 48,51, 61 & 62) PART I MAMMALS [1. Andaman Wild pig (Sus sorofa andamanensis)] 2[1-A. Bharal (Ovisnahura)] 2[1 -B. Binturong (Arctictis Binturong)] 2. Black Buck (Antelope cervicapra) 2[2-A. •*•] 3. Brow-antlered Deer or Thamin (Cervus eldi) 3[3-A. Himalayan Brown bear (Ursus Arctos)] 3[3-B. Capped Langur (Presbytis pileatus)] 4. Caracal (Felis caracal) [4-A. Catecean specials] 5. Cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) 4[5-A. Chinese Pangolin (Mainis pentadactyla)] '[5-B. Chinkara or India Gazelle (Gazella gazella bennetti)] 6. Clouded Leopard (Neofelis nebulosa) 2[6-A. Crab-eating Macaque (Macaca irus umbrosa)] 2[6-B. Desert Cat (Felis libyca)] 3[6-C Desert fox (Vulpes bucapus)] 7. Dugong (Dugong dugon) 2[7-A Ermine (Mustele erminea)] 8. Fishing Cat (Felis viverrina) a[8-A Four-horned antelope (Tetraceros quadricomis)] 2[8-B. *••] 3[8-C ***] 3[8-D. Gangetic dolphin (Platanista gangetica)] 3[8-E. Gaur or Indian bison (Bos gaurus)] 9. Golden Cat (Felis temmincki) 10. Golden Langur (Presbytis geei) 3[10-A. Giant squirrel (Ratufa macroura)] [10-B. Himalayan Ibex (Capra ibex)] ' [10-C. Himalayan Tahr (Hemitragus jemlahicus)] 11. Hispid Hare (Caprolagus hispidus) 3[11-A. Hog badgar (Arconyx collaris)] 12. Hoolock (Hyloba tes hoolock) 1 Vide Notification No. FJ11012/31/76 FRY(WL), dt. 5-10-1977. 2 Vide Notification No. Fl-28/78 FRY(WL), dt. 9-9-1980. 3 Vide Notification No. S.O. 859(E), dt. 24-11-1986. 4 Vide Notification No. F] 11012/31 FRY(WL), dt. -

Annotated Checklist

Butterflies of India – Annotated Checklist By Paul Van Gasse (Kruibeke, Belgium; Email: [email protected]), Aug. 2013. Family Hesperiidae Subfamily Coeliadinae 1. Burara oedipodea (Branded Orange Awlet) B.o.ataphus: Sri Lanka. NR – Ceylon 17 B.o.belesis: Kangra to Arunachal, NE India, and Burma to Dawnas (= aegina, athena) – NW Himalayas (Kangra-Kumaon) 11, Sikkim 30, Bhutan 2, Assam 28, Burma (to Dawnas) 9 B.o.oedipodea: Probably S Burma. [Given as Ismene oedipodea in Evans, 1932, and as Bibasis oedipodea in Evans, 1949] 2. Burara tuckeri (Tucker’s Awlet) Burma in Tavoy. VR – Tavoy 1 [Given as Ismene tuckeri in Evans, 1932, and as Bibasis tuckeri in Evans, 1949] 3. Burara jaina (Orange Awlet) B.j.fergusonii: SW India to N Maharashtra. NR – S India 33 B.j.jaina: HP (Solan) and Garhwal to Arunachal, NE India, and Burma to Karens. NR (= vasundhara) – NW Himalayas (Dun-Kumaon) 3, Sikkim 18, Assam 37, Burma (Karens) 1 B.j.margana: Burma in Dawnas. R – Burma (Dawnas) 8 B.j.astigmata: S Andamans. VR – Andamans 3 [Given as Ismene jaina in Evans, 1932, and vasundhara was there given as the subspecies ranging from Assam to Karens, with jaina then confined to Mussoorie to Sikkim; given as Bibasis jaina in Evans, 1949] 4. Burara anadi (Plain Orange Awlet) Garhwal to NE India and Burma to Karens. R (= purpurea) – Mussoorie 1, Sikkim 13, Assam 1, Burma (Karens) 5 [Given as Ismene anadi in Evans, 1932, and as Bibasis anadi in Evans, 1949] 5. Burara etelka (Great Orange Awlet) NE India (Kabaw Valley in Manipur). -

Priority Conservation Areas for Butterflies (Lepidoptera

Animal Conservation (2004) 7, 79–92 C 2004 The Zoological Society of London. Printed in the United Kingdom DOI:10.1017/S1367943003001215 Priority conservation areas for butterflies (Lepidoptera: Rhopalocera) in the Philippine islands Finn Danielsen1,† and Colin G. Treadaway2 1 NORDECO (Nordic Agency for Development and Ecology), Skindergade 23, DK-1159 Copenhagen, Denmark 2 Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg, Senckenberganlage 25, D-60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany (Received 7 January 2003; accepted 6 August 2003) Abstract Effective representation of all species in local conservation planning is a major challenge, particularly in poorly known but highly fragmented biological ‘hotspots’. Based on 105 months of studies over 49 years, we reviewed the status of 915 species and 910 subspecies of butterflies known in the Philippines. We identified 133 globally threatened and conservation-dependent endemic Philippine taxa. The current system of 18 priority protected areas provides at least one protected area for 65 of these but no areas for 29 species and 39 subspecies. Of the 133 taxa, 71% do not have a stable population inside a priority site. A total of 29 taxa is endangered or critically endangered; 83% of these do not occur within a priority site. Least protected are the lowland taxa. The minimum network required to include each threatened and conservation-dependent taxon of butterfly within at least one area would comprise 29 sites. The Sulus and Mindanao hold disproportionate numbers of threatened butterflies. Our findings suggest limited cross-taxon congruence in complementarity-derived priority sets. A large proportion of the priority areas for Philippine butterflies do not coincide with known priority areas for mammals and birds. -

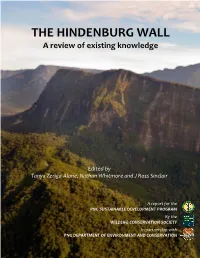

The Hindenburg Wall. a Review of Existing Knowledge

THE HINDENBURG WALL A review of existing knowledge Edited by Tanya Zeriga-Alone, Nathan Whitmore and J Ross Sinclair A report for the PNG SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM By the WILDLIFE CONSERVATION SOCIETY In partnership with PNG DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND CONSERVATION Review of the Hindenburg Wall i c This review is published by: Wildlife Conservation Society Papua New Guinea Program PO BOX 277, Goroka, EHP PAPUA NEW GUINEA Tel: +675-532-3494 [email protected] www.wcs.org Editors: Tanya Zeriga-Alone, Nathan Whitmore and J Ross Sinclair. Contributors: Ken Aplin, Arison Arihafa, Barry Craig, Bensolo Ken, Chris J. Muller and Stephen Richards. The Wildlife Conservation Society is a private, not-for-profit organisation exempt from federal income tax under section 501c(3) of the Inland Revenue Code. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Wildlife Conservation Society or PNG Sustainable Development Program. Acknowledgement: The editors would like to thank the contributing writers and also the following: (PNGSDP) Tricia Caswell, Stanis Tao, Susil Nelson and Ginia Siaguru; (WCS) Zoe Coulson-Sinclair and Seb Delgarno; (DEC) Secretary Gunther Joku and Rose Singadan; (Rocky Roe Photographics) Rocky Roe; (UPNG) Phil Shearman. Images: Rocky Roe (Pages: Front cover, II-VIII, XIV, 1, 4, 7, 8, 24, 40, 60, 63, 74, back cover), Steve Richards (Pages: 19, 27, 28, 36, 84), Ignacio Pazposse (Pages: IX, 21, 31, 37, 41, 61, 64, 75). Suggested citation: Zeriga-Alone, T., Whitmore, N. and Sinclair, R. (editors). 2012. The Hindenburg Wall: A review of existing knowledge. -

A New Approach to Identify Prime Butterfly Areas of Meghalaya, India

et International Journal on Emerging Technologies 10 (2): 440-445(2019) ISSN No. (Print) : 0975-8364 ISSN No. (Online) : 2249-3255 Mapping Butterfly Hotspots: A New Approach to Identify Prime Butterfly Areas of Meghalaya, India Atanu Bora 1, Laishram Ricky Meitei 2 and Sachin Sharma 3 1Meghalaya Biodiversity Board, Sylvan House, 793003 Shillong, (Meghalaya), India. 2Botanical Survey of India, Eastern Regional Centre, 793003 Shillong, (Meghalaya), India. 3Botanical Survey of India, Northern Regional Centre, 248195 Dehradun, (Uttarakhand), India. (Corresponding author: Atanu Bora) (Received 25 May 2019, Revised 02 August 2019 Accepted 18 August 2019) (Published by Research Trend, Website: www.researchtrend.net) ABSTRACT: In India, butterflies are legally protected under various schedules of Indian Wildlife Protection Act, 1972. During the present study, a model consisting of a total of 104 target species listed under Schedule I and II of the act were used to identify the Prime Butterfly Areas (PBAs) of Meghalaya. The selection of PBAs depends highly on the richness, availability and distribution pattern of the target species. A total of 29 PBAs were identified among 7 districts of the state covering National Parks, Wildlife Sanctuaries, Biosphere Reserves, Reserve Forests, Protected Forests, Sacred Groves and all the habitat rich areas that could support a substantial number of the target species. An effort has been made to construct a map of PBAs identified during the study. Agricultural intensification, forest degradation and habitat loss, followed by monoculture, coal mining and burning of forest and vegetation were identified as the principal threats within most of the PBAs. The results of the present study can be used by the conservation agencies to construct a valuable strategy for conservation of target species within PBAs. -

Butterfly Diversity in Different Habitats in Simian Mountain Nature Reserve, China (Insecta: Lepidoptera) SHILAP Revista De Lepidopterología, Vol

SHILAP Revista de Lepidopterología ISSN: 0300-5267 ISSN: 2340-4078 [email protected] Sociedad Hispano-Luso-Americana de Lepidopterología España Yang, Q.-L.; Zeng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Du, X.-C. Butterfly diversity in different habitats in Simian Mountain Nature Reserve, China (Insecta: Lepidoptera) SHILAP Revista de Lepidopterología, vol. 47, no. 188, 2019, October-, pp. 695-704 Sociedad Hispano-Luso-Americana de Lepidopterología España Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=45562243017 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative SHILAP Revta. lepid., 47 (188) diciembre 2019: 695-704 eISSN: 2340-4078 ISSN: 0300-5267 Butterfly diversity in different habitats in Simian Mountain Nature Reserve, China (Insecta: Lepidoptera) Q.-L. Yang, Y. Zeng, Y. Yang & X.-C. Du Abstract Butterflies, as environmental indicators, can act as representatives for less well-monitored insect groups. In this study, a field survey was conducted in five fixed-distance belt transects during three years. Four indices were used to indicate the butterfly diversity. A total of 3004 individuals of 151 species belonging to 82 genera in 6 families were recorded in the survey. Among them, 67 species were recorded in Simian Mountain for the first time, and Celastrina argiolus (Linnaeus, 1758) was the dominant species; Nymphalidae was the dominant family. Among the five habitats, the species diversity of butterfly in Sample V was the highest, closely followed by that in Sample I in which ecological environment was relatively intact; and the diversity of butterfly in Sample IV, in which human interference was strong, was least. -

The Biodiversity Value of the Buton Forests

The biodiversity value of the Buton Forests A 2018 Operation Wallacea Report 1 Contents Executive summary……………...………..………………………………………….……..3 Section 1 – Study site overview...……….………………………………………….………4 Section 2 - Mammals…………...……….………………………………………..………..8 Section 3 – Birds…………..…………………………………………………...…………. 10 Section 4 – Herpetofauna…………………………………………………………….……12 Section 5 – Freshwater fish………………………………………………………….…….13 Section 6 – Invertebrates…………………………………….……………………….……14 Section 7 – Botany…………………………………………...………………………...…..15 Section 8 – Further work…………………………………….………………………...….16 References…………………………………………………….…………………………....22 Appendicies………………………………………………………………………………...24 2 Executive summary - Buton, the largest satellite island of mainland Sulawesi, lies off the coast of the SE peninsular and retains large areas of lowland tropical forest. - The biodiversity of these forests possesses an extremely high conservation value. To date, a total of 53 mammal species, 149 bird species, 64 herpetofauna species, 46 freshwater fish species, 194 butterfly species and 222 tree species have been detected in the study area. - This diversity is remarkably representative of species assemblages across Sulawesi as a whole, given the size of the study area. Buton comprises only around 3% of the total land area of the Sulawesi sub- region, but 70% of terrestrial birds, 54% of snakes and 35% of butterflies known to occur in the region have been found here. - Faunal groups in the forests of Buton also display high incidence of endemism; 83% of native non- volant mammals, 48.9% of birds, 34% of herpetofauna and 55.1% of butterflies found in the island’s forest habitats are entirely restricted to the Wallacean biodiversity hotspot. - Numerous organisms are also very locally endemic to the study area. Three species of herpetofauna are endemic to Buton, and another has its only known extant population here. Other currently undescribed species are also likely to prove to be endemic to Buton. -

LIBROS INCORPORADOS a NUESTRO CATÁLOGO EN 2011 * Precios En Euros

LIBROS INCORPORADOS A NUESTRO CATÁLOGO EN 2011 * Precios en Euros. Gastos de envío e IVA (4%) no incluidos/ Prices in Euro. Postage and VAT (4%) not included ** Recuerde, descuento del 5% para los socios de la SEA y de la AIM (sólo pagos al contado) COLEOPTERA ARNDT, E. ET AL. 2011 GROUND BEETLES (CARABIDAE) OF GREECE . 361 pags, 32 láminas fotos color (espléndidas), figuras b/n, tapas duras . Con claves de determinación ilustradas. Un gran libro. 97 € ASSING, V. 2010 A REVISION OF ACHENIUM (COL.: STAPHYLINIDAE: PAEDERINAE). 190 pags, 471 figs, claves determinación. Bases para la revisión de 6700 especies. 74 € BOUCHARD, P. ET AL. 2011 FAMILY-GROUP NAMES IN COLEOPTERA (INSECTA). 972 pags, tablas, gráficos, tapas blandas. Trabajo conjunto de eminentes especialistas en alta sistemática. Actualizan aspectos nomenclaturales, bibliográficos, etc. 119 € BOUSQUET, Y. 2010 ILLUSTRATED IDENTIFICATION GUIDE TO ADULTS AND LARVAE OF NORTHEASTERN NORTH AMERICAN GROUND BEETLES (CARABIDAE). 562 pags, 91 láminas fotos color y dibujos b/n, 686 figuras b/n, tapas duras. Con claves de determinación. Extraordinario. 92 € CALLOT, H. 2011 CATALOGUE ET ATLAS DES COLEOPTERES D'ALSACE, Tome 18: Scirtidae, Cantharidae, Cleridae, Dasytidae, Malachiidae, Dermestidae, Anobiidae, Byrrhidae. 125 pags, mapas, tapas blandas. Incluye también muchas otras familias pequeñas. 21 € COULON, J. ET AL. 2011 COLEOPTERES CARABIQUES. FAUNE DE FRANCE. COMPLEMENTS AUX DEUX VOLUMES DE RENE JEANNEL, MISE A JOUR, CORRECTIONS ET REPERTOIRE. Vols. 94 & 95. En dos volúmenes alrededor de 600 páginas, ilustrado con 122 láminas de figuras y 28 láminas de fotos en color (250 fotos), con claves de determinación. Vol. 94: Paussidae, carabidae, Nebriidae, Elaphridae, Omophronidae, Loriceridae, Cicindelidae, Siagonidae, Scaritidae, Apotomidae, Broscidae, Psydridae y Trechidae.