CCR8 Expression Defines Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells in Human Skin Michelle L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

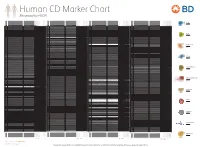

Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse

Welcome to More Choice CD Marker Handbook For more information, please visit: Human bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/humancdmarkers Mouse bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/mousecdmarkers Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse CD3 CD3 CD (cluster of differentiation) molecules are cell surface markers T Cell CD4 CD4 useful for the identification and characterization of leukocytes. The CD CD8 CD8 nomenclature was developed and is maintained through the HLDA (Human Leukocyte Differentiation Antigens) workshop started in 1982. CD45R/B220 CD19 CD19 The goal is to provide standardization of monoclonal antibodies to B Cell CD20 CD22 (B cell activation marker) human antigens across laboratories. To characterize or “workshop” the antibodies, multiple laboratories carry out blind analyses of antibodies. These results independently validate antibody specificity. CD11c CD11c Dendritic Cell CD123 CD123 While the CD nomenclature has been developed for use with human antigens, it is applied to corresponding mouse antigens as well as antigens from other species. However, the mouse and other species NK Cell CD56 CD335 (NKp46) antibodies are not tested by HLDA. Human CD markers were reviewed by the HLDA. New CD markers Stem Cell/ CD34 CD34 were established at the HLDA9 meeting held in Barcelona in 2010. For Precursor hematopoetic stem cell only hematopoetic stem cell only additional information and CD markers please visit www.hcdm.org. Macrophage/ CD14 CD11b/ Mac-1 Monocyte CD33 Ly-71 (F4/80) CD66b Granulocyte CD66b Gr-1/Ly6G Ly6C CD41 CD41 CD61 (Integrin b3) CD61 Platelet CD9 CD62 CD62P (activated platelets) CD235a CD235a Erythrocyte Ter-119 CD146 MECA-32 CD106 CD146 Endothelial Cell CD31 CD62E (activated endothelial cells) Epithelial Cell CD236 CD326 (EPCAM1) For Research Use Only. -

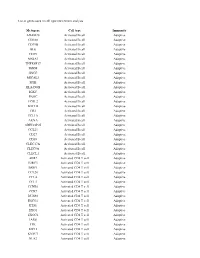

List of Genes Used in Cell Type Enrichment Analysis

List of genes used in cell type enrichment analysis Metagene Cell type Immunity ADAM28 Activated B cell Adaptive CD180 Activated B cell Adaptive CD79B Activated B cell Adaptive BLK Activated B cell Adaptive CD19 Activated B cell Adaptive MS4A1 Activated B cell Adaptive TNFRSF17 Activated B cell Adaptive IGHM Activated B cell Adaptive GNG7 Activated B cell Adaptive MICAL3 Activated B cell Adaptive SPIB Activated B cell Adaptive HLA-DOB Activated B cell Adaptive IGKC Activated B cell Adaptive PNOC Activated B cell Adaptive FCRL2 Activated B cell Adaptive BACH2 Activated B cell Adaptive CR2 Activated B cell Adaptive TCL1A Activated B cell Adaptive AKNA Activated B cell Adaptive ARHGAP25 Activated B cell Adaptive CCL21 Activated B cell Adaptive CD27 Activated B cell Adaptive CD38 Activated B cell Adaptive CLEC17A Activated B cell Adaptive CLEC9A Activated B cell Adaptive CLECL1 Activated B cell Adaptive AIM2 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive BIRC3 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive BRIP1 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive CCL20 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive CCL4 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive CCL5 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive CCNB1 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive CCR7 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive DUSP2 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive ESCO2 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive ETS1 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive EXO1 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive EXOC6 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive IARS Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive ITK Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive KIF11 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive KNTC1 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive NUF2 Activated CD4 T cell Adaptive PRC1 Activated -

CD109 Released from Human Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells Attenuates TGF-Β-Induced Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition and Stemness of Squamous Cell Carcinoma

www.impactjournals.com/oncotarget/ Oncotarget, 2017, Vol. 8, (No. 56), pp: 95632-95647 Research Paper CD109 released from human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells attenuates TGF-β-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition and stemness of squamous cell carcinoma Shufeng Zhou1, Renzo Cecere2 and Anie Philip1 1Division of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada 2Division of Cardiac Surgery, Department of Surgery, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada Correspondence to: Anie Philip, email: [email protected] Keywords: human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells; squamous cell carcinoma; CD109; TGF-β; epithelial to mesenchymal transition Abbreviations: hBM-MSC-CM: human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells conditioned medium; hFibro-CM: human fibroblast cells conditioned medium; EMT: epithelial to mesenchymal transition; SCC: squamous cell carcinoma Received: March 31, 2017 Accepted: July 06, 2017 Published: September 16, 2017 Copyright: Zhou et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC BY 3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. ABSTRACT Although there is increasing evidence that human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (hBM-MSCs) play an important role in cancer progression, the underlying mechanisms are poorly understood. Transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) is an important pro-metastatic cytokine. We have previously shown that CD109, a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein, is a TGF-β co-receptor and a strong inhibitor of TGF-β signalling. Moreover, CD109 can be released from the cell surface. In the current study, we examined whether hBM-MSCs regulate the malignant properties of squamous cell carcinoma cells, and whether CD109 plays a role in mediating the effect of hBM-MSCs on cancer cells. -

Development of Novel Monoclonal Antibodies Against CD109 Overexpressed in Human Pancreatic Cancer

www.oncotarget.com Oncotarget, 2018, Vol. 9, (No. 28), pp: 19994-20007 Research Paper Development of novel monoclonal antibodies against CD109 overexpressed in human pancreatic cancer Gustavo A. Arias-Pinilla1, Angus G. Dalgleish2, Satvinder Mudan3, Izhar Bagwan4, Anthony J. Walker1 and Helmout Modjtahedi1 1School of Life Sciences, Pharmacy and Chemistry, Kingston University London, Kingston-upon-Thames, Surrey, UK 2Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, St George’s University of London, London, UK 3Department of Surgery of Hammersmith Campus, Imperial College, London, UK 4Department of Histopathology, Royal Surrey County Hospital, Guildford, UK Correspondence to: Helmout Modjtahedi, email: [email protected] Keywords: pancreatic cancer; monoclonal antibodies; CD109 antigen; tissue arrays; immunohistochemistry Received: December 10, 2017 Accepted: March 15, 2018 Published: April 13, 2018 Copyright: Arias-Pinilla et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC BY 3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. ABSTRACT Pancreatic cancer is one of the most aggressive and lethal types of cancer, and more effective therapeutic agents are urgently needed. Overexpressed cell surface antigens are ideal targets for therapy with monoclonal antibody (mAb)-based drugs, but none have been approved for the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Here, we report development of two novel mouse mAbs, KU42.33C and KU43.13A, against the human pancreatic cancer cell line BxPC-3. Using ELISA, flow cytometry, competitive assay and immunoprecipitation followed by mass spectrometry, we discovered that these two mAbs target two distinct epitopes on the external domain of CD109 that are overexpressed by varying amounts in human pancreatic cancer cell lines. -

Multiomics of Azacitidine-Treated AML Cells Reveals Variable And

Multiomics of azacitidine-treated AML cells reveals variable and convergent targets that remodel the cell-surface proteome Kevin K. Leunga, Aaron Nguyenb, Tao Shic, Lin Tangc, Xiaochun Nid, Laure Escoubetc, Kyle J. MacBethb, Jorge DiMartinob, and James A. Wellsa,1 aDepartment of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, University of California, San Francisco, CA 94143; bEpigenetics Thematic Center of Excellence, Celgene Corporation, San Francisco, CA 94158; cDepartment of Informatics and Predictive Sciences, Celgene Corporation, San Diego, CA 92121; and dDepartment of Informatics and Predictive Sciences, Celgene Corporation, Cambridge, MA 02140 Contributed by James A. Wells, November 19, 2018 (sent for review August 23, 2018; reviewed by Rebekah Gundry, Neil L. Kelleher, and Bernd Wollscheid) Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia of DNA methyltransferases, leading to loss of methylation in (AML) are diseases of abnormal hematopoietic differentiation newly synthesized DNA (10, 11). It was recently shown that AZA with aberrant epigenetic alterations. Azacitidine (AZA) is a DNA treatment of cervical (12, 13) and colorectal (14) cancer cells methyltransferase inhibitor widely used to treat MDS and AML, can induce interferon responses through reactivation of endoge- yet the impact of AZA on the cell-surface proteome has not been nous retroviruses. This phenomenon, termed viral mimicry, is defined. To identify potential therapeutic targets for use in com- thought to induce antitumor effects by activating and engaging bination with AZA in AML patients, we investigated the effects the immune system. of AZA treatment on four AML cell lines representing different Although AZA treatment has demonstrated clinical benefit in stages of differentiation. The effect of AZA treatment on these AML patients, additional therapeutic options are needed (8, 9). -

CD24, CD27, CD36 and CD302 Gene Expression for Outcome Prediction in Patients with Multiple Myeloma

www.impactjournals.com/oncotarget/ Oncotarget, 2017, Vol. 8, (No. 58), pp: 98931-98944 Research Paper CD24, CD27, CD36 and CD302 gene expression for outcome prediction in patients with multiple myeloma Elina Alaterre6,2, Sebastien Raimbault6, Hartmut Goldschmidt4,5, Salahedine Bouhya7, Guilhem Requirand1,2, Nicolas Robert1,2, Stéphanie Boireau1,2, Anja Seckinger4,5, Dirk Hose4,5, Bernard Klein1,2,3 and Jérôme Moreaux1,2,3 1Department of Biological Haematology, CHU Montpellier, Montpellier, France 2Institute of Human Genetics, CNRS-UM UMR9002, Montpellier, France 3University of Montpellier, UFR Medecine, Montpellier, France 4Medizinische Klinik und Poliklinik V, Universitätsklinikum Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany 5Nationales Centrum für Tumorerkrankungen, Heidelberg, Germany 6HORIBA Medical, Parc Euromédecine, Montpellier, France 7CHU Montpellier, Department of Clinical Hematology, Montpellier, France Correspondence to: Jérôme Moreaux, email: [email protected] Keywords: multiple myeloma; prognostic factor; gene expression profiling; cluster differentiation Received: February 10, 2017 Accepted: August 27, 2017 Published: October 30, 2017 Copyright: Alaterre et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC BY 3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. ABSTRACT Multiple myeloma (MM) is a B cell neoplasia characterized by clonal plasma cell (PC) proliferation. Minimal residual disease monitoring by multi-parameter flow cytometry is a powerful tool for predicting treatment efficacy and MM outcome. In this study, we compared CD antigens expression between normal and malignant plasma cells to identify new potential markers to discriminate normal from malignant plasma cells, new potential therapeutic targets for monoclonal-based treatments and new prognostic factors. -

Expression of CD109 in Human Cancer

Oncogene (2004) 23, 3716–3720 & 2004 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950-9232/04 $25.00 www.nature.com/onc SHORT REPORTS Expression of CD109 in human cancer Mizuo Hashimoto1,2, Masatoshi Ichihara1, Tsuyoshi Watanabe1, Kumi Kawai3, Katsumi Koshikawa4, Norihiro Yuasa2, Takashi Takahashi4, Yasushi Yatabe5, Yoshiki Murakumo1, Jing-min Zhang1, Yuji Nimura2 and Masahide Takahashi*,1,3 1Department of Pathology, Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, 65 Tsurumai-cho, Showa-ku, Nagoya 466-8550, Japan; 2Department of Surgery, Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, 65 Tsurumai-cho, Showa-ku, Nagoya 466-8550, Japan; 3Division of Molecular Pathology, Center for Neural Disease and Cancer, Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, 65 Tsurumai-cho, Showa-ku, Nagoya 466-8550, Japan; 4Division of Molecular Oncology, Aichi Cancer Center Research Institute, 1-1 Kanokoden, Chikusa-ku, Nagoya 464-8681, Japan; 5Department of Pathology and Molecular Diagnsotics, Aichi Cancer Center, 1-1 Kanokoden, Chikusa-ku, Nagoya 464-8681, Japan It was recently reportedthat the human CD109 gene phenotype with the association of MTC, pheochromo- encodes a glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol-anchored glyco- cytoma, and developmental abnormalities such as protein that is a member of the a2-macroglobulin/C3, C4, mucosal neuroma, hyperganglionosis of the intestinal C5 family of thioester-containing proteins. In this study, tract, and marfanoid skeletal changes. To elucidate the we foundthat the expression of mouse CD109 gene was mechanisms of the development of MEN2A and upregulatedin NIH3T3 cells expressing RET tyrosine MEN2B phenotypes, we recently performed differential kinase with a multiple endocrine neoplasia 2B mutation. display analysis to identify the genes that are differen- Northern blot analysis showeda high level of expression tially expressed among NIH 3T3 cells and NIH 3T3 of the CD109 gene only in the testis in normal human and transfectants expressing RET with a MEN2A or mouse tissues. -

Emoglobinuria Parossistica Notturna

EMOGLOBINURIA PAROSSISTICA NOTTURNA Lucio Luzzatto, Scientific Director, Istituto Toscano Tumori Professor of Haematology, University of Firenze. Firenze, ITALY SIE - Corso di Ematologia Cllinica Roma, 29 maggio 2007 PAROXYSMAL NOCTURNAL HAEMOGLOBINURIA: definition Haemolytic anaemia with characteristic clinical triad: 1. Intravascular haemolysis 2. Thrombosis 3. Cytopenias CLASSIFICATION OF HAEMOLYTIC ANAEMIAS Intracorpuscolar Extracorpuscolar causes causes Hereditary •Haemoglobinopaties •Enzimopathies Familial HUS •Membranopathies •Other Acquired •Malaria Paroxysmal •Auto-immune Nocturnal Haemoglobinuria •Drug-induced (PNH) •Micro-angiopathic •Other PAROXYSMAL NOCTURNAL HAEMOGLOBINURIA: classification 1. Hemolytic 2. Hemolytic/hypoplastic 3. Sub-clinical HAEMOGLOBINURIA Indicates intravascular haemolysis WORLDWIDEWORLDWIDE PNHPNH PATIENTSPATIENTS 132132 88 3838 77 3 3 22 Ham Test in a PNH Patient dAcdAc dSdS dAcdAc dHidHi pHipHi pAcpAc HH2 00 Control Patient RBC RBC QuickTime™ and a GIF decompressor are needed to see this picture. Flow-cytometry Analysis of Red Cells from Patients with PNH Control Control Control c o u n t s c o u n t s C.J M.B. R.K PNH III PNH II PNH III normal normal PNH II normal CD59 PROTEINS DEFICIENT ON PNH BLOOD CELLS CD55 B cells CD24 CD55 CD58* CD58* CD59 CD59 CD48 PrPC PrPC CD73 CDw108 AChE JMH Ag Dombroch Hematopoietic HG Ag RBC Stem Cell T cells CD55 CD58* CD59 CD48 CDw52 CD87 CD55 CDw108 PrPc CD58* ADP-RT CD73 CD59 CD90 CD109 CD109 CD59, CD90, CD109 CD16* PrPC GP500 Platelets Gova/b NK cells CD55 CD58* CD55 CD59 CD14 CD58* CD16 CD24 Monocytes CD59 CD48 CD66b PMN CD48 CD66c CD87 CDw52 CD109 CD157 CD14 CD55 CD58* CD59 CD48 CDw52 PrPc LAPNB1 PrPC CD16* p50-80 GPI-80 CD87 CD109 CD157 ADP-RT NA1/NA2 Group 8 PrPC GPI-80 CD16* QuickTime™ and a GIF decompressor All these proteins are GPI-linkedare needed to see this picture. -

Reduced Expression of CD109 in Tumor-Associated Endothelial Cells Promotes Tumor Progression by Paracrine Interleukin-8 in Hepatocellular Carcinoma

www.impactjournals.com/oncotarget/ Oncotarget, Vol. 7, No. 20 Reduced expression of CD109 in tumor-associated endothelial cells promotes tumor progression by paracrine interleukin-8 in hepatocellular carcinoma Bo-Gen Ye1,2,*, Hui-Chuan Sun1,2,*, Xiao-Dong Zhu1,2,*, Zong-Tao Chai3,*, Yuan-Yuan Zhang1,2, Jian-Yang Ao4, Hao Cai1,2, De-Ning Ma1,2, Cheng-Hao Wang1,2, Cheng- Dong Qin1,2, Dong-Mei Gao1,2, Zhao-You Tang1,2 1Liver Cancer Institute and Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China 2Key Laboratory of Carcinogenesis and Cancer Invasion, Ministry of Education, Shanghai 200032, China 3General Surgery, Changhai Hospital, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai 200433, China 4The First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, Wenzhou 325000, China *These authors contributed equally to this work Correspondence to: Zhao-You Tang, e-mail: mail:[email protected]. Keywords: CD109, hepatocellular carcinoma, interleukin-8, TGF-β, tumor-associated endothelial cells Received: November 23, 2015 Accepted: March 28, 2016 Published: April 18, 2016 ABSTRACT Tumor-associated endothelial cells (TEC) directly facilitate tumor progression, but little is known about the mechanisms. We investigated the function of CD109 in TEC and its clinical significance in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The correlation between CD109 expressed on tumor vessels and the prognosis after surgical resection of HCC was studied. The effect of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) with different CD109 expression on hepatoma cell proliferation, migration, and invasion was compared in co-culture assay. Associated key factors were screened by human cytokine antibody array and validated thereafter. HUVEC with different CD109 expression were co-implanted with HCCLM3 or HepG2 cells in nude mice to investigate the effect of CD109 expression on tumor growth and metastasis. -

Characterization of CD109

Characterization of CD109 by Joseph Yao Abotsi Prosper A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Medical Biophysics University of Toronto. © Copyright by Joseph Yao Abotsi Prosper 2011 Characterization of CD109 Joseph Yao Abotsi Prosper Doctor of Philosophy 2011 Department of Medical Biophysics, University of Toronto ABSTRACT: CD109 is a 170kD glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein expressed on subsets of fetal and adult CD34+ haematopoietic stem cells, endothelial cells, activated T cells, and activated platelets. Cloning of the CD109 cDNA by our group identified the molecule as a novel member of the 2M/C3/C4/C5 family of thioester containing proteins. Curiously, CD109 bears features of both the 2M and complement branches of the gene family. Additionally CD109 carries the antigenic determinant of the Gov alloantigen system, which has been implicated in a subset of immune mediated platelet destruction syndromes. In this thesis, the status of CD109 in the evolution and phylogeny of the A2M family has been clarified. First, I elucidated the evolutionary relationships of CD109, and of the other eight human A2M/C3/C4/C5 proteins, using sequence analysis and a detailed comparison of the organization of the corresponding loci. Extension of this analysis to compare CD109 to related sequences extending back to placazoans, defined CD109 as a member of a distinct and archaic branch of the A2M phylogenetic tree. Second, in conjunction with collaborators, the molecular basis of the Gov alloantigen system was identified as an allele specific A2108C; Y703S polymorphism. Utilizing cDNA and genomic sequence we then developed methods to accurately and precisely genotype the Gov system. -

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials Supplementary Text Figs. S1 to S19, Table S1 to S8, Data set 1 Fig. S1. Differential expression of known 69 tumor initiating genes in human normal brain and GBM tissue samples. (A) RNA sequencing analysis. (Upper) Venn diagram representing the number of transcripts (FPKM > 1) up- or down-regulated in human glioblastoma patient samples. (lower) Volcano plots displaying differentially 1 expressed genes. G/N, mean values derived from 20 human glioblastoma,G, samples divided by values from 19 human normal, N, brain tissues. In plot, red dots denote genes that undergo a statistically significant 10-fold change in G/N, either up or down (P < 0.01). Red-labeled dots have G/N ratios greater than 10-fold higher. Blue dot- labeled genes have G/N ratios between 2 to 10. (B) Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation for at least 19 independent specimens. Data are mean ± SD. P value by unpaired 2-tailed Student’s t test 2 Fig. S2. High grade glioma exhibits high CD133 and CD44 markers expression. (A) Low- and high- grade glioma tissue images stained with indicated antibodies were supported by the Human protein atlas (http://www.proteinatlas.org/) or obtained by staining of tissue microarray paraffin sections with CXCR4 antibody (last Panel). (B) Images in fig. S2A were quantified by Image J software. Data are mean ± SD (N>3). P value by unpaired 2-tailed Student’s t test. (C) Tissue microarray paraffin sections from human glioblastoma tissues and normal brain tissues were subjected to immunofluorescent staining using antibodies against CXCR4, CD44, or CD133. -

Reviewed by HLDA1

Human CD Marker Chart Reviewed by HLDA1 T Cell Key Markers CD3 CD4 CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD8 CD1a R4, T6, Leu6, HTA1 b-2-Microglobulin, CD74 + + + – + – – – CD74 DHLAG, HLADG, Ia-g, li, invariant chain HLA-DR, CD44 + + + + + + CD158g KIR2DS5 + + CD248 TEM1, Endosialin, CD164L1, MGC119478, MGC119479 Collagen I/IV Fibronectin + ST6GAL1, MGC48859, SIAT1, ST6GALL, ST6N, ST6 b-Galactosamide a-2,6-sialyl- CD1b R1, T6m Leu6 b-2-Microglobulin + + + – + – – – CD75 CD22 CD158h KIR2DS1, p50.1 HLA-C + + CD249 APA, gp160, EAP, ENPEP + + tranferase, Sialo-masked lactosamine, Carbohydrate of a2,6 sialyltransferase + – – + – – + – – CD1c M241, R7, T6, Leu6, BDCA1 b-2-Microglobulin + + + – + – – – CD75S a2,6 Sialylated lactosamine CD22 (proposed) + + – – + + – + + + CD158i KIR2DS4, p50.3 HLA-C + – + CD252 TNFSF4,