Upholstry Fabric for American Empire Furniture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

French Furniture in the Middle Ages and Under Louis Xiii French Furniture

«IW'T--W!*W'. r,-.,»lk«»«».^*WIWP^5'5.^ Mi|i#|MMiMii^^ B0B€RT>4OlM€S FOK MAMV YEARSATEACHER iH THIS COLLECE.0nP^-.Syi THIS Bffl)K.lSONE9FA)vlUMB9? FROMTJ4E UBJ?AK.y9^JvLR>lOiMES PIJESENTED T01}4EQMTAglO CDltEGE 9^A^ DY HIS RELA.TIVES / LITTLE ILLUSTRATED BOOKS ON OLD FRENCH FURNITURE I. FRENCH FURNITURE IN THE MIDDLE AGES AND UNDER LOUIS XIII FRENCH FURNITURE I. French Furniture in the Middle Ages and under Louis XIII II. French Furniture under Louis XIV III. French Furniture under Loujs XV IV. French Furniture under Louis XVI AND THE Empire ENGLISH FURNITURE (Previously published) I. English Furniture under the Tudors and Stuarts II. English Furniture of the Queen Anne Period III. English Furniture of the Chippen- dale Period IV. English Furniture of the Sheraton Period Each volume profusely illustrated with full-page reproductions and coloured frontispieces Crown SvOf Cloth, price 4s. 6d. net LONDON: WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD. Cupboard in Two Parts (Middle of the XVIth Century) LITTLE ILLUSTRATED BOOKS ON OLD FRENCH FURNITURE I FRENCH FURNITURE IN THE MIDDLE AGES AND UNDER LOUIS XIII BY ROGER DE FELICE Translated by F. M. ATKINSON LONDON MCMXXIII WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD. / OS^'i S5 First published, 1923 Printed in Great Britain hy Woods & Sons, Ltd,f London, N. i. INTRODUCTION A CONSECUTIVE and complete history of French furniture—complete in that it should not leave out the furniture used by the lower middle classes, the artisans and the peasants —remains still to be written ; and the four little books of this series are far from claiming to fill such a gap. -

HERE KS1 Teacher's Notes

KS1 Teacher’s Notes Learning Objectives Working • Ask simple questions and recognise that they can Scientifically be answered in different ways • Observe closely, using simple equipment • Perform simple tests • Identify and classify • Use observations and ideas to suggest answers • Gather and record data to help in answering questions Everyday • Distinguish between an object and the material Materials from which it is made • Describe the physical properties of everyday materials • Compare a variety of everyday materials on the basis of their physical properties • Identify and compare the suitability of a variety of everyday materials for particular uses Cross-curricular links: Speaking and listening, design & technology This plan can be used as a half day workshop or extended into a series of lessons. Summary Pupils will find out about a range of fabrics, their properties and uses through observation, discussion and scientific investigation. They will consolidate their learning through playing a team game, and then use imagination and problem-solving skills to design a garment for the future. You will need (not supplied in this pack): • Examples of 5 or 6 common fabrics made into Fabric Packs e.g. wool, denim, silk, nylon, cotton, fleece. Fabrics should be cut into pieces no smaller than 20cm square. Each pack needs to contain the same fabrics. • Each group/table will need one Fabric Pack • Further fabric pieces for Testing Fabrics investigations • for Investigation 1 we suggest; denim, silk, polyester • for Investigation 2 we suggest: -

John Brown and George Kellogg

John Brown and George Kellogg By Jean Luddy When most people think of John Brown, they remember the fiery abolitionist who attacked pro-slavery settlers in Kansas in 1855 and who led the raid on the Federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1859 in order to spark a slave rebellion. Most people do not realize that Brown was no stranger to Vernon and Rockville, and that he worked for one of Rockville’s prominent 19th century citizens, George Kellogg. John Brown was born in Torrington, CT in 1800. His father was a staunch opponent of slavery and Brown spent his youth in a section of northern Ohio known as an abolitionist district. Before Brown became actively involved in the movement to eliminate slavery, he held a number of jobs, mainly associated with farming, land speculation and wool growing. (www.pbs.org) Brown’s path crossed with George Kellogg’s when Brown started to work for Kellogg and the New England Company as a wool sorter and buyer. John Brown George Kellogg, born on March 3, 1793 in Vernon, got his start in the woolen industry early in life when he joined Colonel Francis McLean in business in 1821. They established the Rock Manufacturing Company and built the Rock Mill, the first factory along the Hockanum River, in the area that would grow into the City of Rockville. Kellogg worked as the company’s agent from 1828 to 1837. At that time, he left the Rock Company to go into business with Allen Hammond. They founded the New England Company and built a factory along the Hockanum River. -

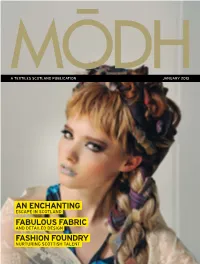

Modh-Textiles-Scotland-Issue-4.Pdf

A TEXTILES SCOTLAND PUBLICATION JANUARY 2013 AN ENCHANTING ESCAPE IN SCOTLAND FABULOUS FABRIC AND DETAILED DESIGN FASHION FOUNDRY NURTURING SCOTTISH TALENT contents Editor’s Note Setting the Scene 3 Welcome from Stewart Roxburgh 21 Make a statement in any room with inspired wallpaper Ten Must-Haves for this Season An Enchanting Escape 4 Some of the cutest products on offer this season 23 A fashionable stay in Scotland Fabulous Fabric Fashion Foundry 6 Uncovering the wealth of quality fabric in Scotland 32 Inspirational hub for a new generation Fashion with Passion Devil is in the Detail 12 Guest contributor Eric Musgrave shares his 38 Dedicated craftsmanship from start to fi nish thoughts on Scottish textiles Our World of Interiors Find us 18 Guest contributor Ronda Carman on why Scotland 44 Why not get in touch – you know you want to! has the interiors market fi rmly sewn up FRONT COVER Helena wears: Jacquard Woven Plaid with Herringbone 100% Merino Wool Fabric in Hair by Calzeat; Poppy Soft Cupsilk Bra by Iona Crawford and contributors Lucynda Lace in Ivory by MYB Textiles. Thanks to: Our fi rst ever guest contributors – Eric Musgrave and Ronda Carman. Read Eric’s thoughts on the Scottish textiles industry on page 12 and Ronda’s insights on Scottish interiors on page 18. And our main photoshoot team – photographer Anna Isola Crolla and assistant Solen; creative director/stylist Chris Hunt and assistant Emma Jackson; hair-stylist Gary Lees using tecni.art by L’Oreal Professionnel and the ‘O’ and irons by Cloud Nine, and make-up artist Ana Cruzalegui using WE ARE FAUX and Nars products. -

An Industrial History of Easthampton G

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1937 An Industrial history of Easthampton G. B. Dennis University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Dennis, G. B., "An Industrial history of Easthampton" (1937). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 1449. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/1449 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UMASS/AMHERST 312066 0306 7762 4 AN INDUSTRIAL HISTORY OF 5ASTHAMFFQN Gr. B. Dennis Thesis Submitted for Degree of Master of Science, Massachusetts State College, Amherst. June 1, 1937 . TABLE OF CONTENTS Outline. Introduction. Map of the Business District of Easthampton. Chapter I. Early History of Easthampton. Page 1. " II. The Industry Founding Period 1227-1276. n 6. » III. Early Transportation, A Problem. n 16. IV. Population Growth and Composition. n 21. " V. Conditions During the Expansion Period. it 30. " VI. Easthampton At the Turn of the Century. n H VII. Population in the New Era 1295-1937 n " VIII. The New Era 1295-I937. n 56. " IX. The Problem of Easthampton Analyzed. n 73- • X. Conclusions and Summary. n 21. References Cited n 26. Appendix I. Tables and Graphs on Population n 22. Appendix II. Tables showing Land in Agriculture n 93. AN INDUSTRIAL HISTORY OF EASTHAMPTON Outline I. Early History. A. Land purchases and settlement. -

Weaving Twill Damask Fabric Using ‘Section- Scale- Stitch’ Harnessing

Indian Journal of Fibre & Textile Research Vol. 40, December 2015, pp. 356-362 Weaving twill damask fabric using ‘section- scale- stitch’ harnessing R G Panneerselvam 1, a, L Rathakrishnan2 & H L Vijayakumar3 1Department of Weaving, Indian Institute of Handloom Technology, Chowkaghat, Varanasi 221 002, India 2Rural Industries and Management, Gandhigram Rural Institute, Gandhigram 624 302, India 3Army Institute of Fashion and Design, Bangalore 560 016, India Received 6 June 2014; revised received and accepted 30 July 2014 The possibility of weaving figured twill damask using the combination of ‘sectional-scaled- stitched’ (SSS) harnessing systems has been explored. Setting of sectional, pressure harness systems used in jacquard have been studied. The arrangements of weave marks of twill damask using the warp face and weft face twills of 4 threads have been analyzed. The different characteristics of the weave have been identified. The methodology of setting the jacquard harness along with healds has been derived corresponding to the weave analysis. It involves in making the harness / ends in two sections; one section is to increase the figuring capacity by scaling the harness and combining it with other section of simple stitching harnessing of ends. Hence, the new harness methodology has been named as ‘section-scale-stitch’ harnessing. The advantages of new SSS harnessing to weave figured twill damask have been recorded. It is observed that the new harnessing methodology has got the advantages like increased figuring capacity with the given jacquard, less strain on the ends and versatility to produce all range of products of twill damask. It is also found that the new harnessing is suitable to weave figured double cloth using interchanging double equal plain cloth, extra warp and extra weft weaving. -

Exceptional Works of Art 2017 PUSHKIN ANTIQUES – MAYFAIR –

Exceptional works of art 2017 PUSHKIN ANTIQUES – MAYFAIR – At Pushkin Antiques we specialise in unique statement Each item is professionally selected and inspected pieces of antique silver as well as branded luxury items, to ensure we can give our customers a guarantee of stylish interior articles and objects d’art. authenticity and the required peace of mind when buying from us. Since the inception of our company, we’ve been at the forefront of online sales for high end, quality antiques. Our retail gallery is located on the lower floor of the world Our presence on most major platforms has allowed us famous Grays Antiques Centre in the heart of Mayfair. to consistently connect exquisite pieces with the most discerning collectors and interior decorators from all over the world with particular focus on the demands of the markets from the Far East, the Americas, Europe & Russia. www.pushkinantiques.com [email protected] We aim to provide the highest quality in every department: rare hand crafted articles, accurate item descriptions (+44) 02085 544 300 to include the history and provenance of each item, an (+44) 07595 595 079 extensive photography report, as well as a smooth buying process thus facilitating an efficient and pleasant online Shop 111, Lower Ground Floor, Grays Antiques Market. experience. 58 Davies St, London. W1K 5AB, UK. ALEX PUSHKIN OLGA PUSHKINA DUMITRU TIRA Founder & Director Managing Director Photographer Contents 6 ENGLISH SILVER 42 CHINESE SILVER 56 JAPANESE SILVER 66 INDIAN SILVER 78 BURMESE SILVER 86 CONTINENTAL SILVER 100 FRENCH SILVER 108 GERMAN SILVER 118 RUSSIAN SILVER 132 OBJECTS OF VERTU English Silver The style and technique in manufacturing silver during Hester Bateman (1708-1794) was one of the greatest this era (over 100 years) changed radically, reflecting silversmiths operating in this style, she is the most the variations in taste, society, costumes, economic and renowned and appreciated female silversmith of all time. -

The Furnishing of the Neues Schlob Pappenheim

The Furnishing of the Neues SchloB Pappenheim By Julie Grafin von und zu Egloffstein [Master of Philosophy Faculty of Arts University of Glasgow] Christie’s Education London Master’s Programme October 2001 © Julie Grafin v. u. zu Egloffstein ProQuest Number: 13818852 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818852 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 l a s g o w \ £5 OG Abstract The Neues SchloB in Pappenheim commissioned by Carl Theodor Pappenheim is probably one of the finest examples of neo-classical interior design in Germany retaining a large amount of original furniture. Through his commissions he did not only build a house and furnish it, but also erected a monument of the history of his family. By comparing parts of the furnishing of the Neues SchloB with contemporary objects which are partly in the house it is evident that the majority of these are influenced by the Empire style. Although this era is known under the name Biedermeier, its source of style and decoration is clearly Empire. -

Korogard® Wall Protection Protect Your Walls in Style

KOROGARD® WALL PROTECTION PROTECT YOUR WALLS IN STYLE. CONTENTS Applications 3 Systems Approach 5 Colors & Finishes 7 Protective Wallcovering 11 Finishing & Installation 15 Corner Guards 16 KOROGARD WALL PROTECTION Handrails 21 Crash & Bumper Rails 26 Chair Rails 31 Door Protection 35 Environmental 37 Technical Information 41 Support & Resources 42 Korogard Wall Protection is a complete line of products and custom solutions that are based on a systems approach. This allows users to mix and match a diverse array of colors while helping to maintain the beauty and style of a space. Unique products, such as Flex™ Decorative Wall Protection and Traffic Patterns®, offer designers the ultimate combination of aesthetics and performance. 1 2 LIMITLESS APPLICATIONS Protecting the beauty of a vertical surface is critical. Korogard has a full line of wall protection solutions for healthcare, education, hospitality, corporate, retail, and more. Unique products are engineered to save time and money by reducing maintenance and replacement costs. Korogard offers an extensive product line with a variety of colors, finishes, and materials to maintain the beauty and style of a designer’s vision for years to come. Assisted Living Athletics Corporate Education Healthcare Hospitality Retail Transit 3 4 A COHESIVE WALL PROTECTION SYSTEMS APPROACH Categories of Wall Protection products: PROTECTIVE CORNER CRASH & DOOR HANDRAILS CHAIR RAILS WALLCOVERINGSWALLCOVERING GUARDS BUMPER RAILS PROTECTORS Protective wallcoverings offer an Offering everything from standard -

Augusta Auction Company Historic Fashion & Textile

AUGUSTA AUCTION COMPANY HISTORIC FASHION & TEXTILE AUCTION MAY 9, 2017 STURBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS 1 TRAINED CHARMEUSE EVENING GOWN, c. 1912 Cream silk charmeuse w/ vine & blossom pattern, empire bodice w/ silk lace & sequin overlay, B to 38", W 28", L 53"-67", (small holes to lace, minor thread pulls) very good. MCNY 2 DECO LAME EVENING GOWN, LATE 1920s Black silk satin, pewter lame in Deco pattern, B to 36", Low W to 38", L 44"-51", excellent. MCNY 3 TWO EMBELLISHED EVENING GOWNS, 1930s 1 purple silk chiffon, attached lace trimmed cape, rhinestone bands to back & on belt, B to 38", W to 31", L 58", (small stains to F, few holes on tiers) fair; 1 rose taffeta underdress overlaid w/ copper tulle & green silk flounce, CB tulle drape, silk ribbon floral trim, B to 38", W 28", L 60", NY label "Blanche Yovin", (holes to net, long light hem stains) fair- good. MCNY 4 RHINESTONE & VELVET EVENING DRESS, c. 1924 Sapphire velvet studded w/ rhinestones, lame under bodice, B 32", H 36", L 50"-53", (missing stones, lame pulls, pink lining added & stained, shoulder straps pinned to shorten for photo) very good. MCNY 5 MOLYNEUX COUTURE & GUGGENHEIM GOWNS, 1930-1950s Both black silk & labeled: 1 late 30s ribbed crepe, "Molyneux", couture tape "11415", surplice bodice & button back, B to 40", W to 34", H to 38", L 58", yellow & black ikat sash included, (1 missing button) excellent; "Mingolini Guggenheim Roma", strapless multi-layered sheath, B 34", W 23", H 35", CL 46"-50", (CF seam unprofessionally taken in by hand, zipper needs replacing) very good. -

Copyrighted Material

14_464333_bindex.qxd 10/13/05 2:09 PM Page 429 Index Abacus, 12, 29 Architectura, 130 Balustrades, 141 Sheraton, 331–332 Abbots Palace, 336 Architectural standards, 334 Baroque, 164 Victorian, 407–408 Académie de France, 284 Architectural style, 58 iron, 208 William and Mary, 220–221 Académie des Beaux-Arts, 334 Architectural treatises, Banquet, 132 Beeswax, use of, 8 Academy of Architecture Renaissance, 91–92 Banqueting House, 130 Bélanger, François-Joseph, 335, (France), 172, 283, 305, Architecture. See also Interior Barbet, Jean, 180, 205 337, 339, 343 384 architecture Baroque style, 152–153 Belton, 206 Academy of Fine Arts, 334 Egyptian, 3–8 characteristics of, 253 Belvoir Castle, 398 Act of Settlement, 247 Greek, 28–32 Barrel vault ceilings, 104, 176 Benches, Medieval, 85, 87 Adam, James, 305 interior, viii Bar tracery, 78 Beningbrough Hall, 196–198, Adam, John, 318 Neoclassic, 285 Bauhaus, 393 202, 205–206 Adam, Robert, viii, 196, 278, relationship to furniture Beam ceilings Bérain, Jean, 205, 226–227, 285, 304–305, 307, design, 83 Egyptian, 12–13 246 315–316, 321, 332 Renaissance, 91–92 Beamed ceilings Bergère, 240, 298 Adam furniture, 322–324 Architecture (de Vriese), 133 Baroque, 182 Bernini, Gianlorenzo, 155 Aedicular arrangements, 58 Architecture françoise (Blondel), Egyptian, 12-13 Bienséance, 244 Aeolians, 26–27 284 Renaissance, 104, 121, 133 Bishop’s Palace, 71 Age of Enlightenment, 283 Architrave-cornice, 260 Beams Black, Adam, 329 Age of Walnut, 210 Architrave moldings, 260 exposed, 81 Blenheim Palace, 197, 206 Aisle construction, Medieval, 73 Architraves, 29, 205 Medieval, 73, 75 Blicking Hall, 138–139 Akroter, 357 Arcuated construction, 46 Beard, Geoffrey, 206 Blind tracery, 84 Alae, 48 Armchairs. -

Cheney Brothers, the New York Connection

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 1998 Cheney Brothers, the New York Connection Carol Dean Krute Wadsworth Atheneum Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Dean Krute, Carol, "Cheney Brothers, the New York Connection" (1998). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 183. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/183 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Cheney Brothers, the New York Connection Carol Dean Krute Wadsworth Atheneum The Cheney Brothers turned a failed venture in seri-culture into a multi-million dollar silk empire only to see it and the American textile industry decline into near oblivion one hundred years later. Because of time and space limitations this paper is limited to Cheney Brothers' activities in New York City which are, but a fraction, of a much larger story. Brothers and beginnings Like many other enterprising Americans in the 1830s, brothers Charles (1803-1874), Ward (1813-1876), Rush (1815-1882), and Frank (1817-1904), Cheney became engaged in the time consuming, difficul t business of raising silk worms until they discovered that speculation on the morus morticaulis, the white mulberry tree upon which the worms fed, might be far more profitable. As with all high profit operations the tree business was a high-risk venture, throwing many investors including the Cheney brothers, into bankruptcy.