The Conquest of Youtube

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cancel Culture: Posthuman Hauntologies in Digital Rhetoric and the Latent Values of Virtual Community Networks

CANCEL CULTURE: POSTHUMAN HAUNTOLOGIES IN DIGITAL RHETORIC AND THE LATENT VALUES OF VIRTUAL COMMUNITY NETWORKS By Austin Michael Hooks Heather Palmer Rik Hunter Associate Professor of English Associate Professor of English (Chair) (Committee Member) Matthew Guy Associate Professor of English (Committee Member) CANCEL CULTURE: POSTHUMAN HAUNTOLOGIES IN DIGITAL RHETORIC AND THE LATENT VALUES OF VIRTUAL COMMUNITY NETWORKS By Austin Michael Hooks A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master of English The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Chattanooga, Tennessee August 2020 ii Copyright © 2020 By Austin Michael Hooks All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT This study explores how modern epideictic practices enact latent community values by analyzing modern call-out culture, a form of public shaming that aims to hold individuals responsible for perceived politically incorrect behavior via social media, and cancel culture, a boycott of such behavior and a variant of call-out culture. As a result, this thesis is mainly concerned with the capacity of words, iterated within the archive of social media, to haunt us— both culturally and informatically. Through hauntology, this study hopes to understand a modern discourse community that is bound by an epideictic framework that specializes in the deconstruction of the individual’s ethos via the constant demonization and incitement of past, current, and possible social media expressions. The primary goal of this study is to understand how these practices function within a capitalistic framework and mirror the performativity of capital by reducing affective human interactions to that of a transaction. -

Von Influencer*Innen Lernen Youtube & Co

STUDIEN MARIUS LIEDTKE UND DANIEL MARWECKI VON INFLUENCER*INNEN LERNEN YOUTUBE & CO. ALS SPIELFELDER LINKER POLITIK UND BILDUNGSARBEIT MARIUS LIEDTKE UND DANIEL MARWECKI VON INFLUENCER*INNEN LERNEN YOUTUBE & CO. ALS SPIELFELDER LINKER POLITIK UND BILDUNGSARBEIT Studie im Auftrag der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung MARIUS LIEDTKE arbeitet in Berlin als freier Medienschaffender und Redakteur. Außerdem beendet er aktuell sein Master-Studium der Soziokulturellen Studien an der Europa-Universität Viadrina in Frankfurt (Oder). In seiner Abschlussarbeit setzt er die Forschung zu linken politischen Influencer*innen auf YouTube fort. DANIEL MARWECKI ist Dozent für Internationale Politik und Geschichte an der University of Leeds. Dazu nimmt er Lehraufträge an der SOAS University of London wahr, wo er auch 2018 promovierte. Er mag keinen akademi- schen Jargon, sondern progressives Wissen für alle. IMPRESSUM STUDIEN 7/2019, 1. Auflage wird herausgegeben von der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung V. i. S. d. P.: Henning Heine Franz-Mehring-Platz 1 · 10243 Berlin · www.rosalux.de ISSN 2194-2242 · Redaktionsschluss: November 2019 Illustration Titelseite: Frank Ramspott/iStockphoto Lektorat: TEXT-ARBEIT, Berlin Layout/Herstellung: MediaService GmbH Druck und Kommunikation Gedruckt auf Circleoffset Premium White, 100 % Recycling Inhalt INHALT Vorwort. 4 Zusammenfassung. 5 Einleitung ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 6 Teil 1 Das Potenzial von YouTube -

Snowschool Offered to Local Students Environment

6 TUESDAY, JANUARY 28, 2020 The Inyo Register SnowSchool offered to local students environment. The second with water. The food color- journey is unique. This Bishop, session allows students to ing and glitter represent game shows students how Mammoth review the first lesson and different, pollutants that water moves through the learn how to calculate snow might enter the watershed, earth, oceans, and atmo- Lakes fifth- water equivalent. The final and students can observe sphere, and gives them a grade students session takes students how the pollutants move better understanding of from the classroom to the and collect in different the water cycle. participate in mountains for a SnowSchool bodies of water. For the final in-class field day. Once firmly in For the second in-class activity, students learn SnowSchool snowshoes, the students activity, students focus on about winter ecology and learn about snow science the water cycle by taking how animals adapt for the By John Kelly hands-on and get a chance on the role of a water mol- winter. Using Play-Doh, Education Manager, ESIA to play in the snow. ecule and experiencing its they create fictional ani- During the in-class ses- journey firsthand. Students mals that have their own For the last five years, sion, students participate break up into different sta- winter adaptations. Some the Eastern Sierra in three activities relating tions. Each station repre- creations in past Interpretive Association to watersheds, the water sents a destination a water SnowSchools had skis for (ESIA) and Friends of the cycle, and winter ecology. molecule might end up, feet to move more easily Inyo have provided instruc- In the first activity, stu- such as a lake, river, cloud, on the snow and shovels tors who deliver the Winter dents create their own glacier, ocean, in the for hands for better bur- Wildlands Alliance’s watershed, using tables groundwater, on the soil rowing ability. -

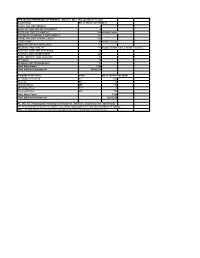

NPR ISSUES/PROGRAMS (IP REPORT) - September 1, 2016 Through September 30, 2016 Subject Key No

NPR ISSUES/PROGRAMS (IP REPORT) - September 1, 2016 through September 30, 2016 Subject Key No. of Stories per Subject AGING AND RETIREMENT 14 AGRICULTURE AND ENVIRONMENT 103 ARTS AND ENTERTAINMENT 187 includes Sports BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND FINANCE 97 CRIME AND LAW ENFORCEMENT 153 EDUCATION 27 includes College IMMIGRATION AND REFUGEES 33 MEDICINE AND HEALTH 67 includes Health Care & Health Insurance MILITARY, WAR AND VETERANS 37 POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT 346 RACE, IDENTITY AND CULTURE 133 RELIGION 12 SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 68 Total Story Count 1277 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 102:40:34 Program Codes (Pro) Code No. of Stories per Show All Things Considered AT 604 Fresh Air FA 35 Morning Edition ME 451 TED Radio Hour TED 8 Weekend Edition WE 179 Total Story Count 1277 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 102:40:34 AT, ME, WE: newsmagazine featuring news headlines, interviews, produced pieces, and analysis FA: interviews with newsmakers, authors, journalists, and people in the arts and entertainment industry TED: excerpts and interviews with TED Talk speakers centered around a common theme Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Aging and Retirement ALL THINGS CONSIDERED 09/01/2016 0:03:53 Dallas Police Chief David Brown Announces Retirement Aging and Retirement MORNING EDITION 09/01/2016 0:02:35 In Visit With Seniors, This Boy Learned Lessons That Go Beyond The Classroom Aging and Retirement WEEKEND EDITION SATURDAY 09/03/2016 0:05:26 After Almost 30 Years As Covering American Politics, Ron Fournier Heads Home Aging and Retirement WEEKEND EDITION SATURDAY -

NPR ISSUES/PROGRAMS (IP REPORT) - March 1, 2021 Through March 31, 2021 Subject Key No

NPR ISSUES/PROGRAMS (IP REPORT) - March 1, 2021 through March 31, 2021 Subject Key No. of Stories per Subject AGING AND RETIREMENT 5 AGRICULTURE AND ENVIRONMENT 76 ARTS AND ENTERTAINMENT 149 includes Sports BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND FINANCE 103 CRIME AND LAW ENFORCEMENT 168 EDUCATION 42 includes College IMMIGRATION AND REFUGEES 51 MEDICINE AND HEALTH 171 includes Health Care & Health Insurance MILITARY, WAR AND VETERANS 26 POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT 425 RACE, IDENTITY AND CULTURE 85 RELIGION 19 SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 79 Total Story Count 1399 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 125:02:10 Program Codes (Pro) Code No. of Stories per Show All Things Considered AT 645 Fresh Air FA 41 Morning Edition ME 513 TED Radio Hour TED 9 Weekend Edition WE 191 Total Story Count 1399 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 125:02:10 AT, ME, WE: newsmagazine featuring news headlines, interviews, produced pieces, and analysis FA: interviews with newsmakers, authors, journalists, and people in the arts and entertainment industry TED: excerpts and interviews with TED Talk speakers centered around a common theme Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Aging and Retirement ALL THINGS CONSIDERED 03/23/2021 0:04:22 Hit Hard By The Virus, Nursing Homes Are In An Even More Dire Staffing Situation Aging and Retirement WEEKEND EDITION SATURDAY 03/20/2021 0:03:18 Nursing Home Residents Have Mostly Received COVID-19 Vaccines, But What's Next? Aging and Retirement MORNING EDITION 03/15/2021 0:02:30 New Orleans Saints Quarterback Drew Brees Retires Aging and Retirement MORNING EDITION 03/12/2021 0:05:15 -

We'll Keep You Rolling Along

4B The herald-News wedNesday, JuNe 17, 2020 TV Guide Listings June 17 - June 23 Ky. Campuses, Education Groups A-DirecTV;B-Dish;C-Brandenburg JUNE 17, 2020 SUNDAYWEEKDAY EVENING AFTERNOONS A-DirecTV;B-Dish;C-Brandenburg JUNE 21, 2020 A B C 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 2:00 2:30 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 A B C 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 Kick Off FAFSA Fridays Campaign 3/WAVE 3 3 3 Days of our Lives Caught Live PD WAVE 3 News WAVE 3 News News News News 3/WAVE 3 3 3 Game Night The Titan Games America’s Got Talent “Auditions 4” WAVE 3 News Greta 7/WTVW News Andy G. Hot Hot Varied Jerry Jerry Springer People’s Court Judge 7/WTVW News Andy G. DC’s Stargirl (S) Supergirl News Theory Family Family FRANKFORT– Kentucky colleges and for college, and ultimately, a successful ca- 9/WNIN Sesame Varied Programs Go Luna Nature ÅWild Molly Xavier Odd Arthur Splash 9/WNIN Prehistoric-Trip Royal Myths Grantchester Beecham House Across the Pacifi c Royal universities along with key leaders in edu- reer. Stakeholders will drive that message 11/WHAS 11 11 11 Pandemic-You General Hospital Blast Blast WHAS11 News News News News 11/WHAS 11 11 11 Celebrity Fam John Legend Press Your Luck Match Game (S) News Osteen NCIS 23/WKZT 4 Varied Programs Pink Dino Cat in Nature Odd Arthur Varied cation launched a new public awareness home every week through the campaign, he 23/WKZT 4 Shakespeare Royal Myths Grantchester Beecham House Modus (S) Wine 32/WLKY 32 32 5 25 Bold The Talk Tamron Hall Young & Restless News NewsÅ News campaign – called FAFSA Fridays – to re- said. -

Different Shades of Black. the Anatomy of the Far Right in the European Parliament

Different Shades of Black. The Anatomy of the Far Right in the European Parliament Ellen Rivera and Masha P. Davis IERES Occasional Papers, May 2019 Transnational History of the Far Right Series Cover Photo: Protesters of right-wing and far-right Flemish associations take part in a protest against Marra-kesh Migration Pact in Brussels, Belgium on Dec. 16, 2018. Editorial credit: Alexandros Michailidis / Shutter-stock.com @IERES2019 Different Shades of Black. The Anatomy of the Far Right in the European Parliament Ellen Rivera and Masha P. Davis IERES Occasional Papers, no. 2, May 15, 2019 Transnational History of the Far Right Series Transnational History of the Far Right Series A Collective Research Project led by Marlene Laruelle At a time when global political dynamics seem to be moving in favor of illiberal regimes around the world, this re- search project seeks to fill in some of the blank pages in the contemporary history of the far right, with a particular focus on the transnational dimensions of far-right movements in the broader Europe/Eurasia region. Of all European elections, the one scheduled for May 23-26, 2019, which will decide the composition of the 9th European Parliament, may be the most unpredictable, as well as the most important, in the history of the European Union. Far-right forces may gain unprecedented ground, with polls suggesting that they will win up to one-fifth of the 705 seats that will make up the European parliament after Brexit.1 The outcome of the election will have a profound impact not only on the political environment in Europe, but also on the trans- atlantic and Euro-Russian relationships. -

Technological Seduction and Self-Radicalization

Journal of the American Philosophical Association () – © American Philosophical Association DOI:./apa.. Technological Seduction and Self-Radicalization ABSTRACT: Many scholars agree that the Internet plays a pivotal role in self- radicalization, which can lead to behaviors ranging from lone-wolf terrorism to participation in white nationalist rallies to mundane bigotry and voting for extremist candidates. However, the mechanisms by which the Internet facilitates self-radicalization are disputed; some fault the individuals who end up self- radicalized, while others lay the blame on the technology itself. In this paper, we explore the role played by technological design decisions in online self- radicalization in its myriad guises, encompassing extreme as well as more mundane forms. We begin by characterizing the phenomenon of technological seduction. Next, we distinguish between top-down seduction and bottom-up seduction. We then situate both forms of technological seduction within the theoretical model of dynamical systems theory. We conclude by articulating strategies for combating online self-radicalization. KEYWORDS: technological seduction, virtue epistemology, digital humanities, dynamical systems theory, philosophy of technology, nudge . Self-Radicalization The Charleston church mass shooting, which left nine people dead, was planned and executed by white supremacist Dylann Roof. According to prosecutors, Roof did not adopt his convictions ‘through his personal associations or experiences with white supremacist groups or individuals or others’ (Berman : ). Instead, they developed through his own efforts and engagement online. The same is true of Jose Pimentel, who in began reading online Al Qaeda websites, after which he built homemade pipe bombs in an effort to target veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan (Weimann ). -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Transgender Gaze, Neoliberal Haze: the impact of neoliberalism on trans female bodies in the Anglophone Global North Gina Gwenffrewi Wordcount 89,758 PhD in English Literature / Transgender Studies The University of Edinburgh 2021 1 Ethical statement This thesis includes the analyses of texts by, or about, trans women of colour. As a white scholar, I am conscious of my privileged position within an academic setting in having this opportunity. I write with a platform that several of these women, and many others who might have had such a platform themselves in a fairer society, lack access to. Aware of this position of power and privilege that I occupy, I state here, at the outset, that I do not claim to speak for or on behalf of the trans women of colour in this thesis. -

Capital Reporting Company U.S. Copyright Office Section 512 Public Roundtable 05-03-2016

Capital Reporting Company U.S. Copyright Office Section 512 Public Roundtable 05-03-2016 1 UNITED STATES COPYRIGHT OFFICE SECTION 512 STUDY + + + + + 9:00 a.m. + + + + + Tuesday, May 3, 2016 Thurgood Marshall United States Courthouse 40 Centre Street New York, New York U.S. COPYRIGHT OFFICE: CINDY ABRAMSON JACQUELINE C. CHARLESWORTH KARYN TEMPLE CLAGGETT RACHEL FERTIG BRAD GREENBERG KIMBERLEY ISBELL (866) 448 - DEPO www.CapitalReportingCompany.com © 2016 Capital Reporting Company U.S. Copyright Office Section 512 Public Roundtable 05-03-2016 2 1 P A R T I C I P A N T S: 2 ALLAN ADLER, Association of American Publishers 3 SANDRA AISTARS, Arts & Entertainment Advocacy Clinic 4 at George Mason University School of 5 JONATHAN BAND, Library Copyright Alliance and Amazon 6 MATTHEW BARBLAN, Center for the Protection of 7 Intellectual Property 8 GREGORY BARNES, Digital Media Association 9 JUNE BESEK, Kernochan Center for Law, Media and the 10 Arts 11 ANDREW BRIDGES, Fenwick & West LLP 12 WILLIAM BUCKLEY, FarePlay, Inc. 13 STEPHEN CARLISLE, Nova Southeastern University 14 SOFIA CASTILLO, Association of American Publishers 15 ALISA COLEMAN, ABKCO Music & Records 16 ANDREW DEUTSCH, DLA Piper 17 TROY DOW, Disney 18 TODD DUPLER, The Recording Academy 19 SARAH FEINGOLD, Etsy, Inc. 20 KATHY GARMEZY, Directors Guild of America 21 JOHN GARRY, Pearson Education 22 MELVIN GIBBS, Content Creators Coalition 23 DAVID GREEN, NBC Universal 24 TERRY HART, Copyright Alliance 25 MICHAEL HOUSLEY, Viacom (866) 448 - DEPO www.CapitalReportingCompany.com © 2016 Capital Reporting Company U.S. Copyright Office Section 512 Public Roundtable 05-03-2016 3 1 P A R T I C I P A N T S 2 SARAH HOWES, Copyright Alliance 3 WAYNE JOSEL, American Society of Composers, Authors 4 and Publishers 5 BRUCE JOSEPH, Wiley Rein LLP (for Verizon) 6 DAVID KAPLAN, Warner Bros. -

Not So Awesome a Record of Events While Working for That Guy with the Glasses

Not So Awesome A record of events while working for That Guy With The Glasses There are many different grievances that need to be shared, but the following points are what we feel are the most grievous and should be known by the public above all others. This is for record/organization and to help clarify and inform. This is not about defamation or destruction, but about clearing the air and correcting misconceptions. For an abridged, simplified account of all grievances, please refer to the condensed version here: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1d7UTXkL5HqywUqNMXwL 5nVG4R84Hr1GX7Phagi15mUo/edit?usp=sharing FOREWORD Thank you for taking the time to read the contents of this document. Within its many pages are lengthy stories from a number of contributors airing their grievances about the way they and others were handled by working professionally with Channel Awesome and the management, namely Mike Michaud, Doug Walker, and Rob Walker. Although the descriptions are vast, this very likely does not cover every possible story of mismanagement over the course of the last ten years. There are other content creators, both those who were previously partnered with Channel Awesome, and those who continue to be partnered with Channel Awesome, who have not contributed their stories to this document, though many of their stories can be found in other places if you look hard enough. There are numerous reasons why any of us would want to share these stories with you. The biggest one is simply a strong common belief that the public deserves the right to know about the dealings within this company. -

Conservative Media's Coverage of Coronavirus On

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Fall 2020 Conservative Media’s Coverage of Coronavirus on YouTube: A Qualitative Analysis of Media Effects on Consumers Michael J. Layer Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Layer, M. J.(2020). Conservative Media’s Coverage of Coronavirus on YouTube: A Qualitative Analysis of Media Effects on Consumers. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ etd/6133 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONSERVATIVE MEDIA’S COVERAGE OF CORONAVIRUS ON YOUTUBE: A QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS OF MEDIA EFFECTS ON CONSUMERS by Michael J. Layer Bachelor of Arts Goucher College, 2017 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in Mass Communications College of Information and Communications University of South Carolina 2020 Accepted by: Linwan Wu, Director of Thesis Leigh Moscowitz, Reader Anli Xiao, Reader Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Michael J. Layer, 2020 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION To the wonderful creators on the internet whose parasocial relationships have taught me so much about the world and myself - namely Olly Thorn, Philosophy Tube; Carlos Maza; Natalie Wynn, Contrapoints; Lindsey Ellis; Bryan David Gilbert; Katy Stoll and Cody Johnson, Some More News; and Robert Evans, Behind the Bastards - thank you. To Dr. Linwan Wu - I am profoundly grateful for your understanding, guidance, and patience.