STAR India's Response to TRAI's Consultation Paper on Tariff Related

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liste Complète Des Chaînes Du Pack Raj IPTV

Liste complète des chaînes du Pack Raj IPTV Indien Pakistan Sud-indien Colors TV HD India ARY Digital Sun TV – Tamil 9X Jalwa (Best) ARY Digital (Feed 2) Jaya Movies – Tamil 9X Music ARY Music Raj TV – Tamil SAB TV Duniya News Raj Music – Malayalam B4U Music HD Express News KTV – Tamil Pogo Hindi Geo News – SD Raj Vissa – Telugu Zee Classic HD Geo News – HD Maa UTV Action HD Geo TV Surya TV – Malayalam B4U Movies HD Geo TV Pak – HD Kantipur TV Times News English Hum TV – HD Nepal Star Plus HD Hum TV – HD (Feed 2) Jeevan – Malayalam Star Gold HD CNBC Pak HD Asia Net News – Malayalam Star Cricket HD Noor TV Zee Marathi Ten Cricket HD Peace TV Star Pravah – Marthi Sony ARY QTV MI Marathi Setmax ARY News HD Uday ATV – Kannada Zee TV HD ARY ZAQU ATN Bangla News Zee Cinema Masala TV NTV HD Zoom TV Express ENT Zee Bangla Zee Jagran / Astha Indus Vision HD Star Viijay - Tamil NDTV Hind News PTV Global NDTV Profit Metero One HD Film Mazia HD Film World HD Dawn News HD Punjabi Anglais Sports & Arabe Sangat TV Animal Planet HD Geo Super HD DD Punjabi National Geo HD News One MH1 BBC World HD Sport 1 HD Chardikala Time TV Cartoon Network Sport 2 HD British Asia Disney Cinemajic Sport 3 HD PTC Punjabi Fox Premier Sport 4 HD PTC News HBO HD Zee Café Zee Punjabi Max Cinema HD Neo Prime Life OK National Geo ADV HD Ten Sport HD AAj TAK News HD Star World HD Dubai Sport HD Ajazeera News Men & Movies Aljazeera Doc HD ETC Punjabi Aljazeera Kids HD RTM 1 – Live Aljazeera Baraem HD RTM 2 – Live Sharjah TV HD MTV India Somali TV HD UTV Movies BBC Arabic HD UTV Star Saudi Arab Saudi Sport . -

11. Mumbai & Thane

11. MUMBAI & THANE Service Name City BST Silver Gold Sony Mumbai & Thane N Y Y Sony SAB Mumbai & Thane N Y Y Colors Mumbai & Thane N Y Y Rishtey Mumbai & Thane N Y Y Sony PAL Mumbai & Thane N Y Y Shop CJ Mumbai & Thane N Y Y Home Shop 18 Mumbai & Thane Y Y Y I D Mumbai & Thane N Y Y Zoom Mumbai & Thane N N Y Epic Mumbai & Thane N N N ETV Bihar JH Mumbai & Thane N Y Y ETV MP CG Mumbai & Thane N Y Y ETV Rajasthan Mumbai & Thane N Y Y ETV UP UK Mumbai & Thane N Y Y DEN snapdeal tv-shop Mumbai & Thane Y Y Y Sahara One Mumbai & Thane N Y Y DD National Mumbai & Thane Y Y Y DD Rajasthan Mumbai & Thane Y Y Y DD Uttar Pradesh Mumbai & Thane Y Y Y DD Madhya Pradesh Mumbai & Thane Y Y Y DD Bihar Mumbai & Thane Y Y Y Sony MAX Mumbai & Thane N Y Y SONY MAX 2 Mumbai & Thane N Y Y B4U Movies Mumbai & Thane N Y Y Cinema TV Mumbai & Thane N Y Y Multiplex Mumbai & Thane Y Y Y DEN Cinema Mumbai & Thane Y Y Y Filmy Mumbai & Thane N N Y DEN Movies Mumbai & Thane N Y Y AXN Mumbai & Thane N Y Y Comedy Central Mumbai & Thane N Y Y Colors Infinity Mumbai & Thane N Y Y DSN INFO Mumbai & Thane Y Y Y Sony PIX Mumbai & Thane N Y Y Movies Now Mumbai & Thane N N Y Romedy Now Mumbai & Thane N N Y Discovery Turbo Mumbai & Thane N Y Y TLC Mumbai & Thane N Y Y Fashion TV Mumbai & Thane N N Y Food Food Mumbai & Thane N N Y News 18 India Mumbai & Thane N Y Y India TV Mumbai & Thane Y Y Y News 24 Mumbai & Thane N N N Aajtak Tez Mumbai & Thane N Y Y ABP News Mumbai & Thane Y Y Y Aajtak Mumbai & Thane N Y Y News Nation Mumbai & Thane Y Y Y India News Mumbai & Thane Y Y Y DD -

Alphabetical Channel Guide 800-355-5668

Miami www.gethotwired.com ALPHABETICAL CHANNEL GUIDE 800-355-5668 Looking for your favorite channel? Our alphabetical channel reference guide makes it easy to find, and you’ll see the packages that include it! Availability of local channels varies by region. Please see your rate sheet for the packages available at your property. Subscription Channel Name Number HD Number Digital Digital Digital Access Favorites Premium The Works Package 5StarMAX 712 774 Cinemax A&E 95 488 ABC 10 WPLG 10 410 Local Local Local Local ABC Family 62 432 AccuWeather 27 ActionMAX 713 775 Cinemax AMC 84 479 America TeVe WJAN 21 Local Local Local Local En Espanol Package American Heroes Channel 112 Animal Planet 61 420 AWE 256 491 AXS TV 493 Azteca America 399 Local Local Local Local En Espanol Package Bandamax 625 En Espanol Package Bang U 810 Adult BBC America 51 BBC World 115 Becon WBEC 397 Local Local Local Local beIN Sports 214 502 beIN Sports (en Espanol) 602 En Espanol Package BET 85 499 BET Gospel 114 Big Ten Network 208 458 Bloomberg 222 Boomerang 302 Bravo 77 471 Brazzers TV 811 Adult CanalSur 618 En Espanol Package Cartoon Network 301 433 CBS 4 WFOR 4 404 Local Local Local Local CBS Sports Network 201 459 Centric 106 Chiller 109 CineLatino 630 En Espanol Package Cinemax 710 772 Cinemax Cloo Network 108 CMT 93 CMT Pure Country 94 CNBC 48 473 CNBC World 116 CNN 49 465 CNN en Espanol 617 En Espanol Package CNN International 221 Comedy Central 29 426 Subscription Channel Name Number HD Number Digital Digital Digital Access Favorites Premium The Works Package -

Supplemental Information

Supplemental Information for the Consolidated Financial Results for the Third Quarter Ended December 31, 2017 2017 年度第 3 四半期連結業績補足資料 February 2, 2018 Sony Corporation ソニー株式会社 Supplemental Financial Data 補足財務データ 2 ■ Average foreign exchange rates 期中平均為替レート 2 ■ Results by segment セグメント別業績 2 ■ Sales to customers by product category (to external customers) 製品カテゴリー別売上高(外部顧客に対するもの) 3 ■ Unit sales of key products 主要製品販売台数 3 ■ Sales to customers by geographic region (to external customers) 地域別売上高(外部顧客に対するもの) 3 ■ Depreciation and amortization (D&A) by segment セグメント別減価償却費及び償却費 4 ■ Amortization of film costs 繰延映画製作費の償却費 4 ■ Additions to long-lived assets and D&A 固定資産の増加額、減価償却費 4 ■ Additions to long-lived assets and D&A excluding Financial Services 金融分野を除くソニー連結の固定資産の増加額、減価償却費及び償却費 4 ■ Research and development (R&D) expenses 研究開発費 5 ■ R&D expenses by segment セグメント別研究開発費 5 ■ Restructuring charges by segment (includes accelerated depreciation expense) セグメント別構造改革費用 5 ■ Period-end foreign exchange rates 期末為替レート 5 ■ Inventory by segment セグメント別棚卸資産 5 ■ Film costs (balance) 繰延映画製作費(残高) 6 ■ Long-lived assets by segment セグメント別固定資産 6 ■ Goodwill by segment セグメント別営業権 6 ■ Return on Invested Capital (ROIC) セグメント別 ROIC 6 Music Segment Supplemental Information (English only) 7 ■ Recorded Music 7 - Recorded Music Revenue breakdown of physical, digital and other revenues - Top 10 best-selling recorded music projects - Noteworthly projects ■ Music Publishing 7 - Number of songs in the music publishing catalog owned and administered Pictures Segment Supplemental Information (English only) 8 ■ Pictures Segment Aggregated U.S. Dollar Information 8 - Pictures segment sales and operating revenue and operating income (loss) - Sales by category and Motion Picture Revenue breakdown - Film costs breakdown ■ Motion Pictures 9 - Motion Pictures Box Office for films released in North America - Select films to be released in the U.S. -

भारतीय Čबंध संùथान, लखनऊ Tender Document for Direct To

भारतीय बंध सं थान ,,, लखनऊ INDIAN INSTITUTE OF MANAGEMENT, LUCKNOW Prabandh Nagar, IIM Road, Lucknow – 226013 TENDER DOCUMENT FOR DIRECT TO HOME SD CONNECTIONS FOR IIM LUCKNOW NIT NO. DT.01/07/2019 Tender No. IIML/PUR/DTH /17/2019-20 Published Date 01/07/2019 Pre Bid Meeting 12/07/2019 at 11:00 AM Last Date of Bid 24/07/2019 upto 02:00 PM Submission Date of Technical 26/07/2019 at 03:00 PM Bid Opening Indian Institute of Management, Lucknow NIT No. IIML/PUR/DTH/17/2019-20 DT.01/07/2019 TENDER FOR DIRECT TO HOME SD CONNECTIONS FOR ONE YEAR Indian institute of Management, Lucknow invites tender from reputed and interested firm/Organization/vendor for Providing Direct to Home SD Connections for IIM Lucknow Campus. For this firm/Organization/vendor should install a centralized installation box for providing Wi-Fi Direct to Home connection all through the campus. User may select channel or choose a package depend upon their interest and capacity to pay. (Package charge must be as per New Guidance of TRAI). Eligibility Criteria The bidder must submit: • All the vendors have to submit a letter of Authorization from OEM indicating that the bidder is authorized to bid for this specific tender. Any OEM directly participate the tender need not submit such letters. • Backend support commitment letter from the OEM specific to this tender by the vendor. OEM should submit a commitment letter along with the tender for providing full onsite support at Lucknow campus. • Submit an undertaking of adequate facilities and manpower (technical staff) to ensure the necessary support to IIM during the warranty period. -

TX-NR636 AV RECEIVER Advanced Manual

TX-NR636 AV RECEIVER Advanced Manual CONTENTS AM/FM Radio Receiving Function 2 Using Remote Controller for Playing Music Files 15 TV operation 42 Tuning into a Radio Station 2 About the Remote Controller 15 Blu-ray Disc player/DVD player/DVD recorder Presetting an AM/FM Radio Station 2 Remote Controller Buttons 15 operation 42 Using RDS (European, Australian and Asian models) 3 Icons Displayed during Playback 15 VCR/PVR operation 43 Playing Content from a USB Storage Device 4 Using the Listening Modes 16 Satellite receiver / Cable receiver operation 43 CD player operation 44 Listening to Internet Radio 5 Selecting Listening Mode 16 Cassette tape deck operation 44 About Internet Radio 5 Contents of Listening Modes 17 To operate CEC-compatible components 44 TuneIn 5 Checking the Input Format 19 Pandora®–Getting Started (U.S., Australia and Advanced Settings 20 Advanced Speaker Connection 45 New Zealand only) 6 How to Set 20 Bi-Amping 45 SiriusXM Internet Radio (North American only) 7 1.Input/Output Assign 21 Connecting and Operating Onkyo RI Components 46 Slacker Personal Radio (North American only) 8 2.Speaker Setup 24 About RI Function 46 Registering Other Internet Radios 9 3.Audio Adjust 27 RI Connection and Setting 46 DLNA Music Streaming 11 4.Source Setup 29 iPod/iPhone Operation 47 About DLNA 11 5.Listening Mode Preset 32 Firmware Update 48 Configuring the Windows Media Player 11 6.Miscellaneous 33 About Firmware Update 48 DLNA Playback 11 7.Hardware Setup 33 Updating the Firmware via Network 48 Controlling Remote Playback from a PC 12 8.Remote Controller Setup 39 Updating the Firmware via USB 49 9.Lock Setup 39 Music Streaming from a Shared Folder 13 Troubleshooting 51 Operating Other Components Using Remote About Shared Folder 13 Reference Information 58 Setting PC 13 Controller 40 Playing from a Shared Folder 13 Functions of REMOTE MODE Buttons 40 Programming Remote Control Codes 40 En AM/FM Radio Receiving Function Tuning into stations manually 2. -

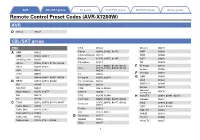

Remote Control Preset Codes (AVR-X7200W) AVR

AVR CBL/SAT group TV group VCR/PVR group BD/DVD group Audio group Remote Control Preset Codes (AVR-X7200W) AVR D Denon 73347 CBL/SAT group CBL CCS 03322 Director 00476 A ABN 03322 Celrun 02959, 03196, 03442 DMT 03036 ADB 01927, 02254 Channel Master 03118 DSD 03340 Alcatel-Lucent 02901 Charter 01376, 01877, 02187 DST 03389 Amino 01602, 01481, 01822, 02482 Chunghwa 01917 DV 02979 Arion 03034, 03336 01877, 00858, 01982, 02345, E Echostar 03452 Cisco 02378, 02563, 03028, 03265, Arris 02187 03294 Entone 02302 AT&T 00858 CJ 03322 F Freebox 01976 au 03444, 03445, 03485, 03534 CJ Digital 02693, 02979 G GBN 03407 B BBTV 02516, 02518, 02980 CJ HelloVision 03322 GCS 03322 Bell 01998 ClubInternet 02132 GDCATV 02980 BIG.BOX 03465 CMB 02979, 03389 Gehua 00476 General Bright House 01376, 01877 CMBTV 03498 Instrument 00476 BSI 02979 CNS 02350, 02980 H Hana TV 02681, 02881, 02959 BT 02294 Com Hem 00660, 01666, 02015, 02832 Handan 03524 C C&M 02962, 02979, 03319, 03407 01376, 00476, 01877, 01982, HCN 02979, 03340 Comcast 02187 Cable Magico 03035 HDT 02959, 03465 Coship 03318 Cable One 01376, 01877 Hello TV 03322 Cox 01376, 01877 Cable&Wireless 01068 HelloD 02979 Daeryung 01877 Cablecom 01582 D Hi-DTV 03500 DASAN 02683 Cablevision 01376, 01877, 03336 Hikari TV 03237 Digeo 02187 1 AVR CBL/SAT group TV group VCR/PVR group BD/DVD group Audio group Homecast 02977, 02979, 03389 02692, 02979, 03196, 03340, 01982, 02703, 02752, 03474, L LG 03389, 03406, 03407, 03500 Panasonic 03475 Huawei 01991 LG U+ 02682, 03196 Philips 01582, 02174, 02294 00660, 01981, 01983, -

Doing Business in Malaysia: 2014 Country Commercial Guide for U.S

Doing Business in Malaysia: 2014 Country Commercial Guide for U.S. Companies INTERNATIONAL COPYRIGHT, U.S. & FOREIGN COMMERCIAL SERVICE AND U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE, 2010-2014. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED OUTSIDE OF THE UNITED STATES. Chapter 1: Doing Business In Malaysia Chapter 2: Political and Economic Environment Chapter 3: Selling U.S. Products and Services Chapter 4: Leading Sectors for U.S. Export and Investment Chapter 5: Trade Regulations, Customs and Standards Chapter 6: Investment Climate Chapter 7: Trade and Project Financing Chapter 8: Business Travel Chapter 9: Contacts, Market Research and Trade Events Chapter 10: Guide to Our Services Return to table of contents Chapter 1: Doing Business In Malaysia Market Overview Market Challenges Market Opportunities Market Entry Strategy Market Overview Return to top For centuries, Malaysia has profited from its location at a crossroads of trade between the East and West, a tradition that carries into the 21st century. Geographically blessed, peninsular Malaysia stretches the length of the Strait of Malacca, one of the most economically and politically important shipping lanes in the world. Capitalizing on its location, Malaysia has been able to transform its economy from an agriculture and mining base in the early 1970s to a relatively high-tech, competitive nation, where services and manufacturing now account for 75% of GDP (51% in services and 24% in manufacturing in 2013). In 2013, U.S.-Malaysia bilateral trade was an estimated US$44.2 billion counting both manufacturing and services,1 ranking Malaysia as the United States’ 20th largest trade partner. Malaysia is America’s second largest trading partner in Southeast Asia, after Singapore. -

Entertainment

TVml August 28, 2020 National Stock Exchange of India Limited BSE Limited Exchange Plaza, Plot No. C/1, P J Towers G-Block Bandra-Kurla Complex, Dalal Street Bandra (E) Mumbai - 400051 Mumbai - 400 001 Trading Symbol: TV18BRDCST SCRIP CODE: 532800 Dear Sirs, Sub: Annual Report for the financial year 2019-20 including Notice of Annual General Meeting The Annual Report for the financial year 2019-20, including the Notice convening Annual General Meeting, being sent to the members through electronic mode, is attached. The Secretarial Audit Report of material unlisted subsidiary is also attached. The Annual Report including Notice is also uploaded on the Company's website www.nw18.com. This is for your information and records. Thanking you, Yours faithfully, For TV18 Broadcast Limited c ~~ ~"OrJ . )," ('.i/'. ~ . .-...e:--.-~ l \ I Ratnesh Rukhariyar Company Secretary Encl. As Above TV18 Broadcast Limited (eIN - L74300MH2005PLC281753) Regd. office: First Floor, Empire Complex, 414- Senopoti Sopot Marg, Lower Parel, Mumboi-400013 T +91 2240019000,66667777 W www.nw18.com E:[email protected] CONTENTS 01 - 11 Corporate Overview 01 Information. Entertainment. Impact TV18 is as unique as 02 Driven to Inform 04 Inspired to Involve it is impactful. It blends 06 Brands that Stimulate compelling and insightful 08 Letter to Shareholders news with inspiring and 09 Corporate Information stimulating entertainment; 10 Board of Directors an attribute that makes it 12 - 68 stand out amongst peers Statutory Reports regardless of size or vintage. 12 Management Discussion and Analysis 29 Board’s Report 40 Business Responsibility Report India’s largest News Broadcast network and the third 49 Corporate Governance Report largest player in the Television entertainment space, TV18 has infused into the Media and Entertainment industry a large dose of youthful dynamism. -

C Ntent 17-30 April 2017 L

C NTENT 17-30 April 2017 www.contentasia.tv l www.contentasiasummit.com Telkomsel, CatchPlay roll out in Indonesia 2GB data sweetener for SVOD movie package Indonesian telco Telkomsel has added Taiwan’s CatchPlay SVOD to its Video- MAX entertainment platform, bundling movies with a 2GB data sweetener and the promise of “smooth streaming” on Telkomsel’s 4G mobile network. The package costs Rp66,000/US$5 a month. CatchPlay has also acquired exclusive digital rights for award winning Indo- nesian movie, Solo, Solitude, which will stream on the platform in May. In addition to the monthly subscription option, a multi-layered pricing strategy offers consumers in Indonesia free mem- bership and one free CatchPlay movie a month, with a pay-per-view option for lo- cal and library titles at Rp19,500/US$1.50 each or new releases for Rp29,500/ US$2.20 each. CatchPlay CEO, Daphne Yang, de- scribed Indonesia as a market of “huge potential in terms of individuals who use the internet for video streaming”. CatchPlay titles include La La Land, Lion and Lego: Batman Movie. New titles this month are Collateral Beauty, starring Will Smith; Sing with Matthew McConaughey and Reese Witherspoon; and Fences with Denzel Washington and Viola Davis. CatchPlay also has a distribution deal with Indihome in Indonesia. The platform is available in Taiwan, where it launched in 2007, Singapore and Indonesia. www.contentasia.tv C NTENTASIA 17-30 April 2017 Page 2. Korea’s JTBC GMA bets on love triangles in new drama breaks new ground 3 wives, 3 husbands, 3 mistresses drive day-time hopes with Netflix 21 April global debut Philippines’ broadcaster GMA Network global linear network GMA Pinoy TV on has premiered its new afternoon drama, 18 April. -

Foreign Satellite & Satellite Systems Europe Africa & Middle East Asia

Foreign Satellite & Satellite Systems Europe Africa & Middle East Albania, Austria, Belarus, Belgium, Bosnia & Algeria, Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Herzegonia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Congo Brazzaville, Congo Kinshasa, Egypt, France, Germany, Gibraltar, Greece, Hungary, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Morocco, Moldova, Montenegro, The Netherlands, Norway, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Somalia, South Africa, Sudan, Tanzania, Tunisia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Uganda, Western Sahara, Zambia. Armenia, Ukraine, United Kingdom. Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Cyprus, Georgia, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, Yemen. Asia & Pacific North & South America Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, Canada, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, China, Hong Kong, India, Japan, Kazakhstan, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Puerto Rico, United Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Macau, Maldives, Myanmar, States of America. Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Nepal, Pakistan, Phillipines, South Korea, Chile, Columbia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Uruguay, Venezuela. Uzbekistan, Vietnam. Australia, French Polynesia, New Zealand. EUROPE Albania Austria Belarus Belgium Bosnia & Herzegovina Bulgaria Croatia Czech Republic France Germany Gibraltar Greece Hungary Iceland Ireland Italy -

Declaration Under Section 4 (4) of the Telecommunication (Broadcasting and Cable) Services Interconnection (Addressable System) Regulation, 2017 (No

Declaration Under Section 4 (4) of The Telecommunication (Broadcasting and Cable) Services Interconnection (Addressable System) Regulation, 2017 (No. 1 of 2017) 4(4)a: Target Market States/Parts of State covered as "Coverage Area" 1. Karnataka 2.Maharashtra 3.Goa 4(4)b: Total Channel carrying capacity Distribution Network Location Capacity in SD Terms Bengaluru (Karnataka) 476 Hubballi (Karnataka) 462 Belagavi (Karnataka) 524 Solapur (Maharashtra) 525 NashiK (Maharashtra) 491 Goa 462 Kindly Note: 1. Local Channels considered as 1 SD; 2. Consideration in SD Terms is clarified as 1 SD = 1 SD; 1 HD = 2 SD; 3. Number of channels will vary within the area serviced by a distribution network location depending upon available Bandwidth capacity 4(4)c: List of channels available on network List attached below in Annexure I 4(4)d: Number of channels which signals of television channels have been requested by the distributor from broadcasters and the interconnection agreements signed Nil 4(4)e: Spare channels capacity available on the network for the purpose of carrying signals of television channels Distribution Network Location Spare Channel Capacity in SD Terms Bengaluru Nil Hubballi Nil Belagavi 50 Solapur 50 NashiK Nil Goa Nil 4(4)f: List of channels, in chronological order, for which requests have been received from broadcasters for distribution of their channels, the interconnection agreements have been signed and are pending for distribution due to non-availability of the spare channel capacity Nil ANNEXURE I Distribution Network Location: