Regulatory Opportunism in Telecommunications: the Unlevel Competitive Playing Field

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sprint Terms and Acronyms

User Guide Sprint Terms and Acronyms All terms and conditions detailed in these Guidelines are subject to change pending future action by the FCC or individual state regulatory commissions. 2 Contents A..............................................................3 B ..............................................................4 C ..............................................................4 D .............................................................6 E ..............................................................7 F ..............................................................8 G..............................................................8 H..............................................................8 I ...............................................................8 J ..............................................................8 L ..............................................................8 M ...........................................................10 N ...........................................................10 O............................................................11 P ............................................................12 R ...........................................................12 S ............................................................13 T ............................................................14 U............................................................14 W...........................................................14 X............................................................14 -

Carrier Locator: Interstate Service Providers

Carrier Locator: Interstate Service Providers November 1997 Jim Lande Katie Rangos Industry Analysis Division Common Carrier Bureau Federal Communications Commission Washington, DC 20554 This report is available for reference in the Common Carrier Bureau's Public Reference Room, 2000 M Street, N.W. Washington DC, Room 575. Copies may be purchased by calling International Transcription Service, Inc. at (202) 857-3800. The report can also be downloaded [file name LOCAT-97.ZIP] from the FCC-State Link internet site at http://www.fcc.gov/ccb/stats on the World Wide Web. The report can also be downloaded from the FCC-State Link computer bulletin board system at (202) 418-0241. Carrier Locator: Interstate Service Providers Contents Introduction 1 Table 1: Number of Carriers Filing 1997 TRS Fund Worksheets 7 by Type of Carrier and Type of Revenue Table 2: Telecommunications Common Carriers: 9 Carriers that filed a 1997 TRS Fund Worksheet or a September 1997 Universal Service Worksheet, with address and customer contact number Table 3: Telecommunications Common Carriers: 65 Listing of carriers sorted by carrier type, showing types of revenue reported for 1996 Competitive Access Providers (CAPs) and 65 Competitive Local Exchange Carriers (CLECs) Cellular and Personal Communications Services (PCS) 68 Carriers Interexchange Carriers (IXCs) 83 Local Exchange Carriers (LECs) 86 Paging and Other Mobile Service Carriers 111 Operator Service Providers (OSPs) 118 Other Toll Service Providers 119 Pay Telephone Providers 120 Pre-paid Calling Card Providers 129 Toll Resellers 130 Table 4: Carriers that are not expected to file in the 137 future using the same TRS ID because of merger, reorganization, name change, or leaving the business Table 5: Carriers that filed a 1995 or 1996 TRS Fund worksheet 141 and that are unaccounted for in 1997 i Introduction This report lists 3,832 companies that provided interstate telecommunications service as of June 30, 1997. -

Federal Communications Commission FCC 04-97 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 in the Matter Of

Federal Communications Commission FCC 04-97 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Petition for Declaratory Ruling that AT&T’s ) WC Docket No. 02-361 Phone-to-Phone IP Telephony Services are ) Exempt from Access Charges ) ) ) ORDER Adopted: April 14, 2004 Released: April 21, 2004 By the Commission: Chairman Powell and Commissioners Abernathy, Copps, Martin, and Adelstein issuing separate statements. I. INTRODUCTION 1. On October 18, 2002, AT&T filed a petition for declaratory ruling that its “phone-to- phone” Internet protocol (IP) telephony services are exempt from the access charges applicable to circuit-switched interexchange calls.1 The service at issue in AT&T’s petition consists of an interexchange call that is initiated in the same manner as traditional interexchange calls – by an end user who dials 1 + the called number from a regular telephone.2 When the call reaches AT&T’s network, AT&T converts it from its existing format into an IP format and transports it over AT&T’s Internet backbone.3 AT&T then converts the call back from the IP format and delivers it to the called party through local exchange carrier (LEC) local business lines.4 We clarify that, under the current rules, the service that AT&T describes is a telecommunications service upon which interstate access charges may be assessed. We emphasize that our decision is limited to the type of service described by AT&T in this proceeding, i.e., an interexchange service that: (1) uses ordinary customer premises equipment (CPE) with no enhanced functionality; (2) originates and terminates on the public switched telephone network (PSTN); and (3) undergoes no net protocol conversion and provides no enhanced functionality to end 1 Petition for Declaratory Ruling that AT&T’s Phone-to-Phone IP Telephony Services are Exempt from Access Charges (filed Oct. -

April 21, 2020 Issued By: Tariff Manager Lancaster, Texas

Intrado Communications, LLC Arkansas P.S.C. No. 9 Original Page 1 ACCESS SERVICES This tariff Intrado Communications, LLC Arkansas P.S.C. No. 9 replaces West Telecom Services, LLC Arkansas P.S.C. No. 6 currently on file with the Commission in its entirety due to Company name change. REGULATION AND SCHEDULE OF INTRASTATE CHARGES GOVERNING THE PROVISION OF SWITCHED ACCESS SERVICES FOR CONNECTION TO COMMUNICATIONS FACILITIES WITHIN THE STATE OF ARKANSAS This tariff contains the descriptions, regulations and rates applicable to the furnishing of competitive access service and facilities for telecommunications services provided by Intrado Communications, LLC within the State of Arkansas. This tariff is on file with the Arkansas Public Service Commission. Copies may be inspected during normal business hours at the Company's principal place of business at 3200 West Pleasant Run Road, Suite 300, Lancaster, Texas 75146. Issued: April 6, 2020 Effective: April 21, 2020 Issued by: Tariff Manager Lancaster, Texas 75146 Intrado Communications, LLC Arkansas P.S.C. No. 9 1st Revised Page 2 Cancels Original Page 2 ACCESS SERVICES CHECK SHEET Sheets of this tariff are effective as of the date shown at the bottom of the respective sheet(s). Original and revised sheets as named below comprise all changes from the original tariff and are currently in effect as of the date on the bottom of this sheet. PAGE REVISION PAGE REVISION 1 Original 31 Original 2 1st Rev. * 32 Original 3 Original 33 Original 4 Original 34 Original 5 Original 35 Original 6 1st Rev. * 36 Original 7 Original 37 Original 8 1st Rev. -

50-30-05 a Guide to Network Access and Pricing Options

50-30-05 A Guide to Network Access and Pricing Previous screen Options Nathan J. Muller Payoff When shopping for services, not only do communications managers have more network access options from which to choose, but more attractive pricing plans as well. Introduction The rate at which net network services are being introduced and price revisions are issued is due as much to the easing of regulatory constraints as to advances in communications technology. Many of the new ways of accessing services can improve networking efficiency. New pricing plans can provide services more economically to users. For the purposes of this article, the different types of access available to users are categorized as basic access, consolidated access, alternate access, and special access. Basic Access Basic access entails the establishment of a physical connection from the customer premises to a local Central Office port. The connection can be dialed up as needed or provided to the user with a dedicated facility, such as a T1 line. Dial-Up Connections In the case of a dial-up connection, once an idle port is seized, the user has access to a variety of services and associated call-handling features provided by the Local Exchange Carrier within its Local Access and Transport Area. If the voice or data call is destined for a location outside the local access and transport area (LATA), the local exchange carrier (LEC) hands it off to a designated interexchange carrier's Point Of Presence, where the call is transported to the local exchange carrier (LEC) at the destination Local Access and Transport Area. -

Abkürzungs-Liste ABKLEX

Abkürzungs-Liste ABKLEX (Informatik, Telekommunikation) W. Alex 1. Juli 2021 Karlsruhe Copyright W. Alex, Karlsruhe, 1994 – 2018. Die Liste darf unentgeltlich benutzt und weitergegeben werden. The list may be used or copied free of any charge. Original Point of Distribution: http://www.abklex.de/abklex/ An authorized Czechian version is published on: http://www.sochorek.cz/archiv/slovniky/abklex.htm Author’s Email address: [email protected] 2 Kapitel 1 Abkürzungen Gehen wir von 30 Zeichen aus, aus denen Abkürzungen gebildet werden, und nehmen wir eine größte Länge von 5 Zeichen an, so lassen sich 25.137.930 verschiedene Abkür- zungen bilden (Kombinationen mit Wiederholung und Berücksichtigung der Reihenfol- ge). Es folgt eine Auswahl von rund 16000 Abkürzungen aus den Bereichen Informatik und Telekommunikation. Die Abkürzungen werden hier durchgehend groß geschrieben, Akzente, Bindestriche und dergleichen wurden weggelassen. Einige Abkürzungen sind geschützte Namen; diese sind nicht gekennzeichnet. Die Liste beschreibt nur den Ge- brauch, sie legt nicht eine Definition fest. 100GE 100 GBit/s Ethernet 16CIF 16 times Common Intermediate Format (Picture Format) 16QAM 16-state Quadrature Amplitude Modulation 1GFC 1 Gigabaud Fiber Channel (2, 4, 8, 10, 20GFC) 1GL 1st Generation Language (Maschinencode) 1TBS One True Brace Style (C) 1TR6 (ISDN-Protokoll D-Kanal, national) 247 24/7: 24 hours per day, 7 days per week 2D 2-dimensional 2FA Zwei-Faktor-Authentifizierung 2GL 2nd Generation Language (Assembler) 2L8 Too Late (Slang) 2MS Strukturierte -

E-Commerce Technology Made Easy

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Journal of Innovative Technology and Research (IJITR) S. Sridhar* et al. (IJITR) INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INNOVATIVE TECHNOLOGY AND RESEARCH Volume No.5, Issue No.3, April – May 2017, 6183-6198. E-Commerce Technology Made Easy S.SRIDHAR Professor & Director RV Centre for Cognitive & Central Computing, R.V.College of Engineering, Mysore Road Bangalore-560059 India Abstract: Electronic Commerce is the Modern Business Methodology To Address, Needs Of Organizations, Merchants, Commerce to Cut Costs and to do the following :-To improve quality/services/speed of delivery; more commonly associated with buying and selling of information, products and services via computer networks today; EDI – Electronic Data Interchange; Latest and dependable way to deliver electronic transactions by computer to computer communication combined with (JIT) ; Just in time manufacturing methods; EDI and email used for many years. e-commerce is a transaction of buying or selling online. Electronic commerce draws on technologies such as mobile commerce, electronic funds transfer, supply chain management, Internet marketing, online transaction processing, electronic data interchange (EDI), inventory management systems, and automated data collection systems. Key words : Modern Business Technology; EDI; Mobile Commerce; Internet Marketing; I. INTRODUCTION 2.1 Elements Of E-Commerce Applications Electronic Commerce is the Modern Business Methodology To Address, Needs Of Organizations, Merchants, Commerce to Cut Costs and to do the following :-To improve quality/services/speed of delivery; more commonly associated with buying and selling of information, products and services via computer networks today; EDI – Electronic Data Interchange; Latest and dependable way to deliver electronic transactions by computer to computer communication combined with (JIT) ; Just in time manufacturing methods; EDI and email used for many years. -

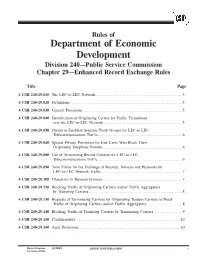

Enhanced Record Exchange Rules

Rules of Department of Economic Development Division 240—Public Service Commission Chapter 29—Enhanced Record Exchange Rules Title Page 4 CSR 240-29.010 The LEC-to-LEC Network...................................................................3 4 CSR 240-29.020 Definitions ......................................................................................3 4 CSR 240-29.030 General Provisions.............................................................................5 4 CSR 240-29.040 Identification of Originating Carrier for Traffic Transmitted over the LEC-to-LEC Network.............................................................5 4 CSR 240-29.050 Option to Establish Separate Trunk Groups for LEC-to LEC Telecommunications Traffic.................................................................6 4 CSR 240-29.060 Special Privacy Provisions for End Users Who Block Their Originating Telephone Number.............................................................6 4 CSR 240-29.080 Use of Terminating Record Creation for LEC-to-LEC Telecommunications Traffic.................................................................6 4 CSR 240-29.090 Time Frame for the Exchange of Records, Invoices and Payments for LEC-to-LEC Network Traffic ..............................................................7 4 CSR 240-29.100 Objections to Payment Invoices .............................................................7 4 CSR 240-29.120 Blocking Traffic of Originating Carriers and/or Traffic Aggregators by Transiting Carriers ........................................................................8 -

6712-01 Federal Communications Commission

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 11/27/2020 and available online at 6712-01 federalregister.gov/d/2020-24624, and on govinfo.gov FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION 47 CFR Part 51 [WC Docket No. 18-156; FCC 20-143; FR ID 17154] 8YY Charge Reform AGENCY: Federal Communications Commission. ACTION: Final rule. SUMMARY: In this document, the Commission takes definitive steps to address the arbitrage and fraud that have increasingly undermined the system of intercarrier compensation that currently underpins toll free calling. Those steps include transitioning 8YY end office originating charges to bill-and-keep over approximately three years and creating a single charge for 8YY tandem switching and transport services and capping it at a lower, uniform rate. The order caps rates for the database queries necessary to route toll free calls, reduces them to a national uniform rate over approximately three years, and limits such database query charges to one per call. Finally, the Commission allows carriers to use existing mechanisms to recover lost revenue. The measures will reduce the incentives for carriers to engage in 8YY access arbitrage and lower the costs of 8YY services overall. DATES: The amendments in this document shall be effective [INSERT DATE 30 DAYS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER], except for §§ 51.907(i) through (k) (instruction 4), 51.909(l) through (o) (instruction 5), and 51.911(e) (instruction 6.b.), which are delayed. The FCC will publish a document in the Federal Register announcing the effective date for those sections. ADDRESSES: Federal Communications Commission, 445 12th Street, SW, Washington, DC 20554. -

RCED-86-66 Telephone Communications: Bypass of The

L United State~‘Gene~al Accounting Office 13txiq6 Repo:fi to the Cong:ress b August 1986 TELEP’HONE COMMUNICATIONS Bypass of the Local Telephone Companies I IIIIllI II 130846 I , I cIIE3~sa.4 GAO/RCED-86-ij0 1/s I I $ ’ “1 , * I United States General Accounting Office GAO Washington, D.C. 20648 Comptroller General of the United States B-203706 August IS,1986 To the President of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives This report provides the results of our work on customers bypassing local telephone companies. We discuss the extent of and reasons for bypass, the impact that bypass may have on local telephone company revenues, and observations on some regulatory actions and proposals that address bypass. We conducted the review because of the concern that local telephone companies could lose billions of dollars if large-volume customers avoid or bypass local telephone company facilities. The report provides the Congress information that may be helpful in oversight and regulation of the nation’s telecommunications industry. We are sending copies of this report to the Director, Office of Management and Budget; the Chairman, Federal Communications Commission; and other interested parties. We will also make copies available to others upon request. Charles A. Bowsher Comptroller General of the United States Executive Summary Local telephone customers could face billions in rate increases if the Purpose local telephone companies lose their large-volume customers due to bypass. Bypass occurs when customers use available technologies, such as microwave and satellite transmission facilities, to avoid using certain local telephone company facilities. -

Federal Communications Commission § 64.1903

Federal Communications Commission § 64.1903 § 64.1902 Terms and definitions. the service originates outside the inde- pendent LEC’s local exchange areas. Terms used in this part have the fol- Local Exchange Carrier. The term lowing meanings: local exchange carrier means any per- Books of account. Books of account son that is engaged in the provision of refer to the financial accounting sys- telephone exchange service or ex- tem a company uses to record, in mon- change access. Such term does not in- etary terms, the basic transactions of a clude a person insofar as such person is company. These books of account re- engaged in the provision of a commer- flect the company’s assets, liabilities, cial mobile service under section 332(c), and equity, and the revenues and ex- except to the extent that the Commis- penses from operations. Each company sion finds that such service should be has its own separate books of account. included in the definition of that term. Incumbent Independent Local Exchange Carrier (Incumbent Independent LEC). [64 FR 44425, Aug. 16, 1999] The term incumbent independent local § 64.1903 Obligations of all incumbent exchange carrier means, with respect independent local exchange car- to an area, the independent local ex- riers. change carrier that: (a) An incumbent independent LEC (1) On February 8, 1996, provided tele- providing in-region, interstate, inter- phone exchange service in such area; exchange services or in-region inter- and national interexchange services shall (2)(i) On February 8, 1996, was deemed provide such services through an affil- to be a member of the exchange carrier iate that satisfies the following re- association pursuant to § 69.601(b) of quirements: this title; or (1) The affiliate shall maintain sepa- (ii) Is a person or entity that, on or rate books of account from its affili- after February 8, 1996, became a suc- ated exchange companies. -

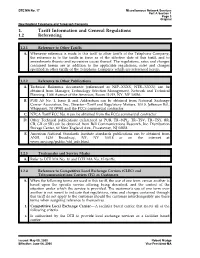

1. Tariff Information and General Regulations 1.2 Referencing

DTE MA No. 17 Miscellaneous Network Services Part A Section 1 Page 3 Original New England Telephone and Telegraph Company 1. Tariff Information and General Regulations 1.2 Referencing 1.2.1 Reference to Other Tariffs A. Whenever reference is made in this tariff to other tariffs of the Telephone Company, the reference is to the tariffs in force as of the effective date of this tariff, and to amendments thereto and successive issues thereof. The regulations, rates and charges contained herein are in addition to the applicable regulations, rates and charges specified in other tariffs of the Telephone Company which are referenced herein. 1.2.2 Reference to Other Publications A. Technical Reference documents (referenced as NIP – XXXX, NTR – XXXX) can be obtained from Manager, Technology Selection Management, Network and Technical Planning, 1166 Avenue of the Americas, Room 11015, NY, NY 10036. B. PUB AS No. 1, Issue II and Addendum can be obtained from National Exchange Carrier Association, Inc., Director – Tariff and Regulatory Matters, 100 S. Jefferson Rd., Whippany, NJ 07981 and the FCCs commercial contractor. C. NECA Tariff FCC No. 4 can be obtained from the FCCs commercial contractor. D. Other Technical publications (referenced as PUB, TR – NPL, TR – TSV, TR – TSY, BR, CB, GR or SR) can be obtained from Bell Communications Research, Inc. Distribution Storage Center, 60 New England Ave., Piscataway, NJ 08854. E. American National Standards Institute standards publications can be obtained from ANSI, 1430 Broadway, NY, NY 10018 or on the internet at www.ansi.org/public/std_info.html. 1.2.3 Trademarks and Service Marks A.