Effects of Content and Source Cues of Online Satirical News on Perceived Believability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Loud Public: Users' Comments and the Online News Media

The Loud Public: Users' Comments and the Online News Media Na'ama Nagar∗ [email protected] April 13, 2009 ∗This paper is a first draft, please do not cite. If you would like an updated version of the paper feel free to contact me. 1 Introduction Research has already established that the availability of interactive features in news sites distinguishes online journalism from its offline counterparts (Pavlik 2000; Deuze and Paulussen 2002). Interactivity signifies a shift from the traditional media one-to-many communication flow to the emergence of a two-way communication model which converts online audiences from pas- sive to active media consumers (Pavlik 2001). The potential of interactivity to facilitate a dialogue between the media and its audiences is therefore in- disputable. Nonetheless, a series of studies has demonstrated that the use of interactive features by mainstream news sites is relatively limited, espe- cially features that promote user-to-user interactions (Chung 2004; Deuze 2003; Domingo 2008; Kenney et al. 2000; Massey and Levy 1999; Quinn and Trench 2000; Rosenberry 2005; Schultz 2000).1 This paper focuses primar- ily on mainstream news sites for two reasons. First, these sites are some of the most popular news sources in the World Wide Web (Rosenberry 2005). Additionally, these sites represent prominent offline news organizations and thus are more likely to be perceived as authoritative sources. Most research thus far on interactivity and the news media is mainly con- cerned with the integration of interactive features as a whole (Chung 2004, 2007; Domingo 2008; Massey and Levy 1999). This approach is important because it helps us to understand the aggregated effect of these features on the news production process. -

Missouri Photojournalism Hall of Fame Induction Program, Oct. 17, Washington, Mo

September 2013 Geri Migielicz Missouri Newspaper Hall of Fame will induct 5 during the MPA Con- 7 vention in Kansas City. Bob Linder Missouri Photojournalism Hall of Fame Induction Program, Oct. 17, Washington, Mo. Foundation work com- 4 pleted on MPA building 5 in Columbia. Jim Miller Jr. Regular Features President 2 Scrapbook 12 On the Move 10 NIE Report 15 Obituaries 11 Jean Maneke 17 Missouri Press News, September 2013 www.mopress.com Digital Footprint a powerful new tool! Your advertisers want, need online presence ery soon you’re going to start hearing more about stated by Nienhueser. Digital Footprint, the Missouri Press Service’s name “Another goal of this program will be to enhance the rela- Vfor a new package of services you’ll be able to offer to tionship between Missouri Press Service and the newspapers,” local businesses. You will hear a little about Digital Footprint he said. “With better and more frequent promotion of MPS at the MPA Convention in Kansas City. products, we can’t help but generate more revenue Missouri Press will promote Digital Foot- for everyone. We think the newspapers will ap- print to its member newspapers and to po- preciate that.” tential users of the services around the state To help implement this program, the Missouri and country. We’re going to provide member Press board approved the hiring of another sales newspapers with material they can use to pro- person and a graphic designer. Patton, mentioned mote these services in their markets. above, is the designer; the sales person might be We’ve got a new graphics designer, Jeremy on staff by the time you read this. -

A Comparative Analysis on News Values: Comparing Coverage of Education in South Korea and the United States✝

Korean Social Science Journal 2011, Vol. 38, No. 1, pp. 99~132 Comparative Review A Comparative Analysis on News Values: Comparing Coverage of Education in South Korea and the United States✝ Jae Chul Shim* (Professor, School of Journalism and Mass Communication, Korea University) Wan Kyu Jung** (Lecturer, Division of Political Science, Public Administration and Journalism, Wonkwang University) Kyun Soo Kim*** (Assistant Professor, Department of Mass Communication, Grambling State University) Abstract This study investigates how Korean major dailies covered educational issues regarding universities, and compares its findings with those of leading American newspapers. The results show that Korean newspapers covered the universities much more negatively than their American counterparts did. Korean newspapers also demonstrated lower journalistic standards as compared with the American newspapers. There were some gaps in terms of news values in covering education at the college level between Korean and American newspapers. Nevertheless, these professional gaps were not too wide to be bridged. In addition, Ettema and Glasser’s three new news values of investigative reporting were not unique from the traditional ones in this study. They were mixed with those of fairness and professional reporting. From these findings, we discuss typical characteristics of Korean newspaper coverage and suggest new ways of covering the education beats in South Korea as a newly advanced and democratized country. Key words: Educational Reform, News Values, Comparative Journalistic Standards, Education Reporting, University News, Diversity, New Long Journalism 100 … Jae Chul Shim, Wan Kyu Jung, and Kyun Soo Kim ✝ This paper was originally written in Korean and published in The Korean Journal of Journalism and Communication Studies in 2003. -

Ethics in Photojournalism: Past, Present, and Future

Ethics in Photojournalism: Past, Present, and Future By Daniel R. Bersak S.B. Comparative Media Studies & Electrical Engineering/Computer Science Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2003 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SEPTEMBER, 2006 Copyright 2006 Daniel R. Bersak, All Rights Reserved The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: _____________________________________________________ Department of Comparative Media Studies, August 11, 2006 Certified By: ___________________________________________________________ Edward Barrett Senior Lecturer, Department of Writing Thesis Supervisor Accepted By: __________________________________________________________ William Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies Director Ethics In Photojournalism: Past, Present, and Future By Daniel R. Bersak Submitted to the Department of Comparative Media Studies, School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences on August 11, 2006, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies Abstract Like writers and editors, photojournalists are held to a standard of ethics. Each publication has a set of rules, sometimes written, sometimes unwritten, that governs what that publication considers to be a truthful and faithful representation of images to the public. These rules cover a wide range of topics such as how a photographer should act while taking pictures, what he or she can and can’t photograph, and whether and how an image can be altered in the darkroom or on the computer. -

Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2017 On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era Amanda Kay Martin University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Amanda Kay, "On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/ Colbert Era. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4759 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Amanda Kay Martin entitled "On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Communication and Information. Barbara Kaye, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Mark Harmon, Amber Roessner Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Amanda Kay Martin May 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Amanda Kay Martin All rights reserved. -

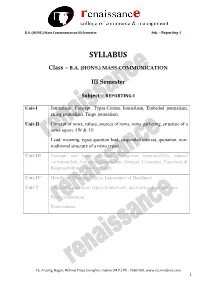

Class – BA (HONS.) MASS COMMUNICATION III Semester

B.A. (HONS.) Mass Communication III Semester Sub. – Reporting-I SYLLABUS Class – B.A. (HONS.) MASS COMMUNICATION III Semester Subject – REPORTING-I Unit-I Journalism: Concept, Types-Citizen Journalism, Embeded journalism, string journalism, Tingo journalism. Unit-II Concept of news, values, sources of news, news-gathering, structure of a news report. 5W & 1H Lead: meaning, types question lead, suspended interest, quotation, non- traditional structure of a news report. Unit-III Concept and kinds of beat. Categories reporters-City, special correspondent, foreign correspondent, Stringer, Columnist, Functions & Responsibilities, follow-up story. Unit-IV Headlines: Meaning, Types, Importance of Headlines. Unit-V What is an interview, types of interview, interviewer & its qualities. Press conferences. Press release. 45, Anurag Nagar, Behind Press Complex, Indore (M.P.) Ph.: 4262100, www.rccmindore.com 1 B.A. (HONS.) Mass Communication III Semester Sub. – Reporting-I UNIT-I & II JOURNALISM - INTRODUCTION Journalism is the practice of investigating and reporting events, issues and trends to the mass audiences of print, broadcast and online media such as newspapers, magazines and books, radio and television stations and networks, and blogs and social and mobile media. The product generated by such activity is called journalism. People who gather and package news and information for mass dissemination are journalists. The field includes writing, editing, design and photography. With the idea in mind of informing the citizenry, journalists cover individuals, organizations, institutions, governments and businesses as well as cultural aspects of society such as arts and entertainment. News media are the main purveyors of information and opinion about public affairs. WHAT DOES A JOURNALIST DO? The main intention of those working in the journalism profession is to provide their readers and audiences with accurate, reliable information they need to function in society. -

The Online News Genre Through the User Perspective

The Online News Genre through the User Perspective Carina Ihlström Jonas Lundberg Viktoria Institute, and Department of Computer and Information School of Information Science, Computer and Science, Linköping University, Electrical Engineering, S-581 83 Linköping, Sweden Halmstad University, P.O Box 823, E-mail: [email protected] S-301 18 Halmstad, Sweden E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The audience has also started to use the online newspapers in different ways depending on whether they Online newspapers, having existed on the Internet for a are subscribers to the printed edition or not. The couple of years, are now having similar form and content, subscribers use the online edition primarily as a source for starting to shape what could be called a genre. We have updated news during the day. The non-subscribers also analyzed the news sites of nine Swedish local newspapers use the online edition as their source for local news [4]. using a repertoire of genre elements consisting of The similarity of use by audience groups also contributes navigation elements, landmarks, news streams, headlines, to the shaping of a genre. search/archives and advertisements. We have also Genres mediate between communities, creating interviewed 153 end users at these newspapers. The expectations and helping people to find and create "more objective of this paper is to describe the user’s perspective of the same" [5]. For example, categorizing a movie as an of the online news genre described in terms of the "action movie" both helps the creators and the audience to repertoire of genre elements. -

Telling Stories to a Different Beat: Photojournalism As a “Way of Life”

Bond University DOCTORAL THESIS Telling stories to a different beat: Photojournalism as a “Way of Life” Busst, Naomi Award date: 2012 Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Telling stories to a different beat: Photojournalism as a “Way of Life” Naomi Verity Busst, BPhoto, MJ A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Media and Communication Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Bond University February 2012 Abstract This thesis presents a grounded theory of how photojournalism is a way of life. Some photojournalists dedicate themselves to telling other people's stories, documenting history and finding alternative ways to disseminate their work to audiences. Many self-fund their projects, not just for the love of the tradition, but also because they feel a sense of responsibility to tell stories that are at times outside the mainstream media’s focus. Some do this through necessity. While most photojournalism research has focused on photographers who are employed by media organisations, little, if any, has been undertaken concerning photojournalists who are freelancers. -

Reporting Techniques & Skills

Edited with the trial version of Foxit Advanced PDF Editor To remove this notice, visit: www.foxitsoftware.com/shopping Reporting Techniques & Skills Study Material for Students 1 Edited with the trial version of Foxit Advanced PDF Editor To remove this notice, visit: www.foxitsoftware.com/shopping Reporting Techniques & Skills CAREER OPPORTUNITIES IN MEDIA WORLD Mass communication and Journalism is institutionalized and source specific. It functions through well-organized professionals and has an ever increasing interlace. Mass media has a global availability and it has converted the whole world in to a global village. A qualified journalism professional can take up a job of educating, entertaining, informing, persuading, interpreting, and guiding. Working in print media offers the opportunities to be a news reporter, news presenter, an editor, a feature writer, a photojournalist, etc. Electronic media offers great opportunities of being a news reporter, news editor, newsreader, programme host, interviewer, cameraman, producer, director, etc. Other titles of Mass Communication and Journalism professionals are script writer, production assistant, technical director, floor manager, lighting director, scenic director, coordinator, creative director, advertiser, media planner, media consultant, public relation officer, counselor, front office executive, event manager and others. 2 Edited with the trial version of Foxit Advanced PDF Editor To remove this notice, visit: www.foxitsoftware.com/shopping : Reporting Techniques & Skills INTRODUCTION The book deals with techniques of reporting. The students will learn the skills of gathering news and reporter’s art of writing the news. The book explains the basic formula of writing the news and the kinds of leads. Students will also learn different types of reporting and the importance of clarity and accuracy in writing news. -

Fake News Vs Satire: a Dataset and Analysis

Session: Best of Web Science 2018 WebSci’18, May 27-30, 2018, Amsterdam, Netherlands Fake News vs Satire: A Dataset and Analysis Jennifer Golbeck, Matthew Mauriello, Brooke Auxier, Keval H Bhanushali, Christopher Bonk, Mohamed Amine Bouzaghrane, Cody Buntain, Riya Chanduka, Paul Cheakalos, Jeannine B. Everett, Waleed Falak, Carl Gieringer, Jack Graney, Kelly M. Hoffman, Lindsay Huth, Zhenye Ma, Mayanka Jha, Misbah Khan, Varsha Kori, Elo Lewis, George Mirano, William T. Mohn IV, Sean Mussenden, Tammie M. Nelson, Sean Mcwillie, Akshat Pant, Priya Shetye, Rusha Shrestha, Alexandra Steinheimer, Aditya Subramanian, Gina Visnansky University of Maryland [email protected] ABSTRACT Fake news has become a major societal issue and a technical chal- lenge for social media companies to identify. This content is dif- ficult to identify because the term "fake news" covers intention- ally false, deceptive stories as well as factual errors, satire, and sometimes, stories that a person just does not like. Addressing the problem requires clear definitions and examples. In this work, we present a dataset of fake news and satire stories that are hand coded, verified, and, in the case of fake news, include rebutting stories. We also include a thematic content analysis of the articles, identifying major themes that include hyperbolic support or con- demnation of a figure, conspiracy theories, racist themes, and dis- crediting of reliable sources. In addition to releasing this dataset for research use, we analyze it and show results based on language that are promising for classification purposes. Overall, our contri- bution of a dataset and initial analysis are designed to support fu- Figure 1: Fake news. -

News for a New Generation: Can It Be Fun and Functional?

News for A New Generation: Can it Be Fun and Functional? Susan Sherr Eagleton Institute of Politics Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey [email protected] CIRCLE WORKING PAPER 29 MARCH 2005 CIRCLE Working Paper 29: March 2005 News for a New Generation: Can it be Fun and Functional? CIRCLE Working Paper 28: February News for a New Generation: Can it be Fun and Functional? INTRODUCTION programs (Pew Center for the People and the Press, 2004). However, it is far too pessimistic to assume that the only options available to young people for Considerable time and financial resources information gathering must be flawed news sources have been dedicated to increasing the numbers that do not appeal to them or comedy shows that of young people who vote in the United States. have no mandate to inform. Voting is certainly a vital component of political and civic engagement. However, there are other News media organizations have an obvious important political behaviors in which young people interest in increasing the youth audience but not have been participating in decreasing numbers and necessarily in providing young people with high at rates lower than older people. One example is quality information about politics and public affairs. news consumption. Even if 18-24 year olds begin Efforts to increase youth audiences by news voting at consistently higher rates, their relative organizations generally include providing more inattention to political information may prevent entertainment coverage, shortening the length of them from casting informed votes. news stories and adjusting formal visual features to be more consistent with “MTV Style” editing (Sherr, Many recent studies and practitioner reports CIRCLE Working Paper 16, 2004). -

Examples of Fake News Relevant for Young People

EXAMPLES OF FAKE NEWS RELEVANT FOR YOUNG PEOPLE FOSTERING INTERNET LITERACY FOR YOUTH WORKERS AND TEACHERS WITH A FOCUS ON FAKE NEWS This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication [communication] reflects only the views of the author. Therefore The Commission cannot be held responsible for any eventual use of the information contained therein. Project No. 2017-3-AT02-KA205-001979 EXAMPLES OF FAKE NEWS RELEVANT FOR YOUNG PEOPLE As we are dealing with the fake news here in the project it is important to recognize how the real fake news look like, faced or confronted by children and young people on an everyday basis. To do this, we have asked European youth to send us the fake news. Below are the examples of topics young people are interested in and through which they are exposed to fake news. They are divided in the following spheres of their interest: www.fake-off.eu 02 Fun and Animal Created by Barbara Buchegger (OIAT/Saferinternet.at) 03 Stars and society, celebrities Matthias Jax (OIAT/Saferinternet.at) 13 Food and Diets Tetiana Katsbert (YEPP EUROPE) 14 Body image and Sexuality Jochen Schell (YEPP EUROPE) 19 Social networks and Manipulation 22 Health Contributions by Ulrike Maria Schriefl (LOGO jugendmanagement) 30 Life-Style, Beauty, Shopping, Fashion Thomas Doppelreiter (LOGO jugendmanagement) 33 World, technology and crime Stefano Modestini (GoEurope) 40 Propaganda and Politics Javier Milán López (GoEurope) 54 Scaremongering, Hoax and Group Pressure Alice M. Trevelin (Jonathan Cooperativa Sociale) Dario Cappellaro (Jonathan Cooperativa Sociale) 64 Nature, Environment Marisa Oliveira (Future Balloons) Vítor Andrade (Future Balloons) Clara Rodrigues (Future Balloons) Michael Kvas (bit schulungscenter) David Kargl (bit schulungscenter) Laura Reutler (bit schulungscenter Graphic design by Marcel Fernández Pellicer (GoEurope) This project has been funded with support from the European Commission.