A Dramaturgical Study of Merrythought's Songs in <Em>The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Your-Song-Elton-John-String-Trio.Pdf

Your Song Elton John String Trio Sheet Music Download your song elton john string trio sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 6 pages partial preview of your song elton john string trio sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 7041 times and last read at 2021-10-04 10:16:05. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of your song elton john string trio you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Cello, Piano, Viola, Violin Ensemble: Mixed Level: Intermediate [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Your Song Elton John Arranged For String Trio Your Song Elton John Arranged For String Trio sheet music has been read 4104 times. Your song elton john arranged for string trio arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-10-05 19:05:12. [ Read More ] Your Song Elton John Clarinet Trio Your Song Elton John Clarinet Trio sheet music has been read 3565 times. Your song elton john clarinet trio arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-10-06 05:15:44. [ Read More ] Your Song Elton John Arranged For String Duet Your Song Elton John Arranged For String Duet sheet music has been read 4929 times. Your song elton john arranged for string duet arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 5 preview and last read at 2021-10-05 20:04:15. -

“Quiet Please, It's a Bloody Opera”!

UNIVERSITETET I OSLO “Quiet Please, it’s a bloody opera”! How is Tommy a part of the Opera History? Martin Nordahl Andersen [27.10.11] A theatre/performance/popular musicology master thesis on the rock opera Tommy by The Who ”Quiet please, it’s a bloody opera!” Martin Nordahl Andersen 2011 “Quiet please, it’s a bloody opera!” How is Tommy part of the Opera History? Print: Reprosentralen, University of Oslo All photos by Ross Halfin © All photos used with written permission. 1 ”Quiet please, it’s a bloody opera!” Aknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisors Ståle Wikshåland and Stan Hawkins for superb support and patience during the three years it took me to get my head around to finally finish this thesis. Thank you both for not giving up on me even when things were moving very slow. I am especially thankful for your support in my work in the combination of popular music/performance studies. A big thank you goes to Siren Leirvåg for guidance in the literature of theatre studies. Everybody at the Institute of Music at UiO for helping me when I came back after my student hiatus in 2007. I cannot over-exaggerate my gratitude towards Rob Lee, webmaster at www.thewho.com for helping me with finding important information on that site and his attempts at getting me an interview with one of the boys. The work being done on that site is fantastic. Also, a big thank you to my fellow Who fans. Discussing Who with you makes liking the band more fun. -

Elton John Page.Cdr

Elton John Music Titles Available from The Music Box, 30/31 The Lanes, Meadowhall Centre Sheffield S9 1EP Write with cheque made out to TMB Retail Music Ltd. or your card details or phone us on 0114 256 9089 Monday to Friday 10am- 8.45pm, Saturday 9am to 6.45pm or Sunday 11am to 4.30pm Elton John - Greatest Hits 1970-2002 IMP9807A £14.99 UK Postage £2.25 Your Song - Tiny Dancer - Honky Cat - Rocket Man (I Think It's Going To Be A Long, Long Time) - Crocodile Rock - Daniel - Saturday Night's Alright (For Fighting) - Goodbye Yellow Brick Road - Candle In The Wind - Bennie And The Jets - Don't Let The Sun Go Down On Me - The Bitch Is Back - Philadelphia Freedom - Someone Saved My Life Tonight - Island Girl - Don't Go Breaking My Heart - Sorry Seems To Be The Hardest Word - Blue Eyes - I'm Still Standing - I Guess That's Why They Call It The Blues - Sad Songs (Say So Much) - Nikita - Sacrifice - The One - Kiss The Bride - Can You Feel The Love Tonight - Circle Of Life - Believe - Made In England - Something About The Way You Look Tonight - Written In The Stars - I Want Love - This Train Don't Stop There Anymore - Song For Guy The Very Best Of Elton John BGP83627 £12.99 UK Postage £2.25 All the tracks from the definitive Elton John album of the same name for voice, piano and guitar chord boxes with full lyrics. Bennie And The Jets - Blue Eyes - Candle In The Wind - Crocodile Rock - Daniel - Don't Let The Sun Go Down On Me - Dont Go Breaking My Heart - Easier To Walk Away - Goodbye Yellow Brick Road - Honky Cat - I'm Still Standing - I Don't -

QUINCY SYMPHONY CHORUS PROGRAM NOTES British Invasion ~ March 9, 2019 Dr

QUINCY SYMPHONY CHORUS PROGRAM NOTES British Invasion ~ March 9, 2019 Dr. Carol Mathieson Andrew Lloyd Webber relaunched musical theatre in the 1960’s in ways that welcomed electronic technology and rock music without allowing ephemeral fads to highjack well-crafted composition. And audiences responded, with younger aficionados swelling the general flock to the theatres. Tonight’s medley follows chronologically from earliest efforts with Tim Rice to turn Jesus Christ, Superstar— a scripture story recast in rock, produced as a concept album with basic plot, all the songs, and minimal dialog—into a stage show, opening in London’s West End. It was a mega-hit. Soon after came Evita about the Perón dictatorship in Argentina. Rice did not feel comfortable remolding established writing into lyrics, so for Cats, Lloyd Webber went directly to T.S. Eliot’s poetry. Song and Dance is a short musical play with lyrics by Don Black, paired with a short ballet with music Lloyd Webber wrote for his cellist brother Julien as variations on a Paganini caprice. However, Phantom of the Opera, with Charles Hart lyrics, was back to high drama. Phantom smashed attendance records in both London and New York, running for decades. Tonight’s medley opens and closes with songs from that iconic show. Nineteenth-century English musical theatre consisted of cheerful song and dance revues or badly translated, risqué French burlesques until Gilbert and Sullivan brought satirical, silly Savoy Operas to a family-friendly stage. QSC sings highlights from the first and the final masterpieces of these saviors of both the English and American musical stage. -

Assignment: Final Projects

Upward Bound STEM July 25, 2013 Assignment: Final Projects The culmination of this Music+STEM course is the creation of new songs by groups of students. Here are our expectations for this assignment: You may work individually or in groups of 2 to 5. The larger the size of the group, the better the finished product is expected to be. Your song should cover some aspect of STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics). Please cover specific STEM content, as opposed to making vague, general statements that require no understanding (like “Math is really fun” or “Cells are so important”). In particular, we challenge you to go beyond textbook facts to include some tidbits about the history of a problem, how experiments are currently done and/or what kinds of data have been collected. (For example, we consider “Myofibrils” [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GC_CUfLP6Pc] a facts-only song, whereas “Necessary But Not Sufficient” [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8HX34kHHDow] offers a taste of the data underlying the conclusions.) Your song can be in any musical genre (blues, rock, rap, country, gospel, reggae, etc.). Your song can be completely original, or it can be a parody of an existing song. However, it should be created by YOU. Do NOT hand in a song that you found on the Internet! This assignment is due on the final day of class (Thursday, August 1st). You will do a short presentation/performance of your song at that time. In addition, you should hand in the following: Lyrics sheet for your song Musical score (if original music) for your song “Artists’ Statement” explaining your song. -

IM Still Standing Elton John Taron Egerton

I M Still Standing Elton John Taron Egerton Sheet Music Download i m still standing elton john taron egerton sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 5 pages partial preview of i m still standing elton john taron egerton sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 9043 times and last read at 2021-09-30 18:25:48. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of i m still standing elton john taron egerton you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Handbell, Percussion Ensemble: Handbell Choir Level: Advanced [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music I M Still Standing G Minor By Elton John Piano I M Still Standing G Minor By Elton John Piano sheet music has been read 2707 times. I m still standing g minor by elton john piano arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 2 preview and last read at 2021-09-30 17:08:04. [ Read More ] I M Still Standing Elton John Sheet Music Easy Piano I M Still Standing Elton John Sheet Music Easy Piano sheet music has been read 3191 times. I m still standing elton john sheet music easy piano arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 1 preview and last read at 2021-09-30 08:10:48. [ Read More ] I M Still Standing G Minor By Elton John Easy Piano I M Still Standing G Minor By Elton John Easy Piano sheet music has been read 2883 times. -

English Music Elton John Part 2

English Music Elton John Part 2 In 1967, John answered an ad for a songwriter for Liberty Records. He got the job and soon teamed up with lyricist Bernie Taupin. The duo switched to the DJM label the following year, writing songs for other artists. John got his first break as a singer with his 1969 album Empty Sky, featuring songs by John and Taupin. While that recording failed to catch on, his 1970 self-titled effort featured John’s first hit “Your Song.” More hits soon followed, including such number- one smashes as “Crocodile Rock,” “Bennie and the Jets” and “Island Girl.” John enjoyed a series of top-selling albums during this time, including Goodbye Yellow Brick Road (1973) and Rock of the Westies (1975). As one of the top acts of the 1970s, Elton John became equally famous for his live shows. He dressed in fabulous, over-the-top costumes and glasses for his elaborate concerts. In an interview with W, John explained that “I wasn’t a sex symbol like Bowie, Marc Bolan or Freddie Mercury, so I dressed more on the humorous side, because if I was going to be stuck at the piano for two hours, I was going to make people look at me.” Elton John – Your Song It’s a little bit funny this feeling inside I’m not one of those who can easily hide I don’t have much money but boy if I did I’d buy a big house where we both could live If I was a sculptor, but then again, no Or a man who makes potions in a travelling show I know it’s not much but it’s the best I can do My gift is my song and this one’s for you And you can tell everybody this is your -

Elton John: I'm Still Standing–A Grammy® Salute," to Be Broadcast Tuesday, April 10 on Cbs Elton John Also Takes the Stage to Perform a Medley of His Timeless Hits

MUSIC STARS HONOR ELTON JOHN ON THE ROCKIN' TRIBUTE "ELTON JOHN: I'M STILL STANDING–A GRAMMY® SALUTE," TO BE BROADCAST TUESDAY, APRIL 10 ON CBS ELTON JOHN ALSO TAKES THE STAGE TO PERFORM A MEDLEY OF HIS TIMELESS HITS SANTA MONICA, CALIF. (MARCH 13, 2018)—Music stars Alessia Cara, Miley Cyrus, Kesha, Lady Gaga, Miranda Lambert, John Legend, Little Big Town, Chris Martin, Shawn Mendes, Maren Morris, Ed Sheeran, Sam Smith, and SZA celebrate the illustrious career of Elton John on the tribute special "Elton John: I'm Still Standing–A GRAMMY® Salute," to be broadcast Tuesday, April 10 (9–11 p.m., ET/PT) on the CBS Television Network. The concert showcases musicians from multiple genres performing classic songs from Elton John's impressive music catalog with longtime co-writer Bernie Taupin and features special appearances by Jon Batiste, Neil Patrick Harris, Christopher Jackson, Anna Kendrick, Gayle King, Lucy Liu, Valerie Simpson, and Hailee Steinfeld. Following is the list of performances featured on "Elton John: I'm Still Standing–A GRAMMY Salute": "The Bitch Is Back" — Miley Cyrus "Candle In The Wind" — Ed Sheeran "Daniel" — Sam Smith "I Guess That's Why They Call It The Blues" — Alessia Cara "Your Song" — Lady Gaga "Rocket Man" — Little Big Town "Border Song" — Christopher Jackson & Valerie Simpson "Don't Go Breaking My Heart" — SZA & Shawn Mendes "Mona Lisas And Mad Hatters" — Maren Morris "We All Fall In Love Sometimes" — Chris Martin "My Father's Gun" — Miranda Lambert "Goodbye Yellow Brick Road" — Kesha "Don't Let The Sun Go Down -

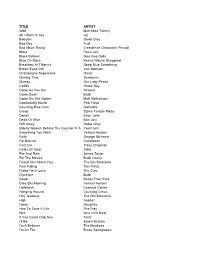

Matt Colligan Song List 2017

TITLE ARTIST 3AM Matchbox Twenty All I Want Is You U2 Babylon David Gray Bad Day Fuel Bad Moon Rising Creedence Clearwater Revival Black Pearl Jam Black Balloon Goo Goo Dolls Blue On Black Kenny Wayne Sheppard Breakfast At Tiffany's Deep Blue Something Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison Champagne Supernova Oasis Closing Time Semisonic Clumsy Our Lady Peace Collide Howie Day Come As You Are Nirvana Come Down Bush Come On Get Higher Matt Nathanson Comfortably Numb Pink Floyd Counting Blue Cars Dishwalla Creep Stone Temple Pilots Daniel Elton John Dead Or Alive Bon Jovi Drift Away Dobie Gray Elderly Woman Behind The Counter In A SmallPearl Town Jam Everything You Want Vertical Horizon Faith George Michaels Far Behind Candlebox Fast Car Tracy Chapman Fields Of Gold Stink Fire And Rain James Taylor For The Movies Buck Cherry Found Out About You The Gin Blossoms Free Falling Tom Petty Friday I'm In Love The Cure Glycerine Bush Good Better Than Ezra Grey Sky Morning Vertical Horizon Hallelujah Leanard Cohen Hanging Around Counting Crows Hey Jealousy The Gin Blossoms High Feeder Home Daughtry How To Save A Life The Fray Hurt Nine Inch Nails If You Could Only See Tonic I'll Be Edwin McCain I'm A Believer The Monkees I'm On Fire Bruce Springsteen In Your Eyes Peter Gabriel Interstate Love Song Stone Temple Pilots Keep On Rockin' In The Free World Neil Young Learn To Fly The Foo Fighters Learning To Fly Tom Petty Let Her Cry Hootie And The Blowfish Lips Of An Angel Hinder Little Wonders Rob Thomas Lost Highways Bon Jovi Love Song The Cure Low Cracker Maggie Mae Rod Stewart Margaritaville Jimmy Buffett Molly Sponge Mr. -

A Dramaturgical Study of Merrythought's Songs in the Knight

Early Theatre 12.2 (2009) Katrine K. Wong A Dramaturgical Study of Merrythought’s Songs in The Knight of the Burning Pestle ‘Let him stay at home and sing for his dinner’, advises Mistress Merrythought about her highly musical husband, Old Merrythought, who believes in achiev- ing mirth and health through much singing, a good portion of which has the pretext of conviviality, in particular, drinking.1 The philosophy embedded in Old Merrythought’s sundry songs in Francis Beaumont’s The Knight of the Burning Pestle (c 1607)2 shows the coexistence of orderliness and disor- derliness related to music, a duality pervasive in the use of music in English Renaissance drama. Early modern English culture attached a wide range of associations to music; various pairs of ideological dichotomies can be identi- fied, such as sublimation and corruption of the soul, love and lust, masculin- ity and femininity, and destruction and restoration of sanity.3 In this essay, I first provide a brief contextual background of the perception and practice of music, and illustrate with a few episodes from Elizabethan and Jacobean plays the diversity of connotations carried by music as well as how music can be incorporated into various types of dramatic scenarios.4 These examples reflect the general musical landscape of Renaissance drama. I then evaluate the dramaturgical characteristics of Merrythought’s songs in relation to the contemporary cultural and dramatic milieux. Views on Music The negotiation between the divine and the corrupting in music has always been an important part of the social and philosophical understanding of the art since classical times. -

Larson 1919 3424498.Pdf

The Treatment of Royalty_ In The Plays of Beaumont and Fletcher • .l!lphild Larson A Thesis submitted ·to the Department of English and the Faculty of the Graduate School of the .University of ·Kansas in partial fulfillment of the Requirements !or a Master's Degree. Approved~ t.,-/J ~ . _Dept~ June 1919. TABLE OF.CONTENTS. Preface. I. Introduction. II. An Analysis of the Plays in Which Royalty Appears. III. Types of Royalty Treated by Beaumont and Fletcher. IV. Divine Right in Beaumont and .Fletcher's Plays. V:. Beaumont and Fletcher's Purpose in Treating Royalty. Conclusion. Chronology of Beaumont ·and Fletcher's Plays in which ,Royalty Appear.a. Bibliography. Index of Characters· and Plays. PBEFACE . The Treatment of Royalty in Beaumont and Fletcher, was suggested by Professor W.S':•Johnson as a subject for this . ) ~ thesis. I~ has not been my task to distinguish the part of each dramatist in regard to authorship. S.inoe the Duke i~ these plays is treated as a Sovereign ruler, he has been included in the study of royalty ·~as ;well as the King, Queen, Prince,. and Princess. I wish to extend my gratitude to Professor W.S.Johnson for his kind and helpful .criti_oi·sm in the preparation of this thesis, and also to Professor S.L.Whitoomb for his beneficial and.needful suggestions• A.• L. ' 1. INTRODUCTION Iri order to appreciate the sy.mpathies and interests of Beaumont and Fletcher, we need to have , a general knowledge· of the national life of England during their time. We also need to know something about the English drama of .this per- iod to understand why our dramatists favored the treatment of·. -

Bursts of Memory

JourneysA newsletter to help with grief Spring 2018 | Kansas City Hospice & Palliative Care Bursts of Memory by Jacque Amweg, Grief Support Specialist his morning when I skin and recalled wearing the we can often find comfort “What is lovely walked outside my long blue and white flowered in these memories. At those front door and smelled dress that a friend loaned me. times it’s almost like we’ve Tthe cool air, a memory popped I wore it all day one Saturday been given a surprise gift of never dies, into my mind. I was instantly when I was thirteen. I sat on the former place and time to taken to my grandparents the sidewalk and played jacks enjoy. but passes back yard, the narrow in it. Yet memories of happy sidewalk that went out to the The sight of the moon times can be painful in grief alley, the long length of grassy through the trees has taken for awhile. It helps to share into another yard that sloped up to another me back to the memory of a them in some way, talking to level in the middle of the soft, tentative kiss. Not long someone, writing in a journal loveliness, yard, and the “north house” ago I was dozing off and in or blog or creating traditions they called it. It was a storage my sleepy state was taken around those memories. shed in the back yard that was back to the nights of rocking If you would like to speak star-dust or surrounded by hollyhocks.