Submission to the Inquiry Into Options for Financing Faster Rail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Nsw Rail Timetables Rail and Tram News

AUSTRALASIAN TIMETABLE NEWS No. 268, December 2014 ISSN 1038-3697 RRP $4.95 Published by the Australian Timetable Association www.austta.org.au NEW NSW RAIL TIMETABLES designated as Hamilton Yard (Hamilton Station end) and Sydney area Passenger WTT 15 Nov 2014 Hamilton Sidings (Buffer Stop end). Transport for NSW has published a new Passenger Working Timetable for the Sydney area, version 3.70. Book 2 The following sections of the Working Timetable will be re- Weekends is valid from 15 November, and Book 1 issued with effect from Saturday 3 January 2015: • Weekdays valid from 17 November. There appear to be no Section 7- Central to Hornsby-Berowra (All Routes) significant alterations other than the opening of Shellharbour • Section 8- City to Gosford-Wyong-Morisset- Junction station closing of Dunmore station. A PDF of the Broadmeadow-Hamilton new South Coast line Public timetable can be accessed from • Section 9- Hamilton to Maitland-Dungog/Scone. the Sydney trains website. Cover pages, Explanatory Notes and Section Maps will also be issued. Additionally, amendments to Section 6 will need Sydney area Freight WTT 15 Nov 2014 to be made manually to include updated run numbers and Transport for NSW has published a new Freight Working changes to Sydney Yard working as per Special Train Notice Timetable for the Sydney area, version 3.50. Book 5 0034-2015. The re-issued sections of Books 1 & 2 will be Weekends is valid from 15 November, and Book 4 designated as Version 3.92, and replace the corresponding Weekdays valid from 17 November. There appear to be no sections of Working Timetable 2013, Version 3.31, reprint significant alterations. -

Student Welcome & Pre-Arrival Information Pack

Student Welcome & Pre-Arrival Information Pack Congratulations on choosing ANU College as your place of study! We are looking forward to meeting you and welcoming you into the ANU College community. The following information will help you prepare for your arrival in Canberra. You should read this pack along with the information on the ANU College website in order to be fully prepared when settling into your new study environment. We strongly advise you to download and read the Australian Government Guide to Studying and living in Australia. It is full of useful information. www.studyinaustralia.gov.au Introducing Canberra Canberra is Australia's national capital city, located in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT). Nestled around a series of man-made lakes and surrounded by natural bushland, Canberra is a modern, safe and international-friendly city that offers a healthy learning environment equal to the best in Australia. International students, in particular, are well-catered for in the range of quality institutions and in the programs these institutions offer. Canberra can offer international students: • Cosmopolitan lifestyle • Safe and pollution free environment • Wide range of recreational activities • Home to national art and cultural institutions • All the advantages of a big city in an accessible, safe, multicultural environment. For further information on how to experience Canberra, refer to the official site of Canberra tourism: http://www.canberratourism.com.au/. It is a comprehensive guide on what to see and do in the capital city of Australia. (Source: www.educationcapital.canberra.edu.au) ANU College Contact Details ANU College The Australian National University 95 Daley Road Acton 2601 ACT Telephone: Outside Australia: (+61 2) 6125 6688 Outside Canberra: (02) 6125 6688 Within Canberra: 6125 6688 Emergency Telephone Numbers Police, Fire, Ambulance – 000 Hospitals There are two public hospitals in Canberra: 1. -

Australia's #1

BUY AND SELL BUSES WITH AUSTRALIa’S #1 BUS CLASSIFIEDS BUY More than 400 buses and coaches to choose from SELL Maximise your ads exposure online & in ABC magazine. To list your ad call 03 9567 4154 today! ABC-FP-5016473-CS-325-X INSIDE GOLD COAST CONFERENCE & EXPO PROGRAM Issue 324 AUGUST 2014 $5.95 inc GST PP100008045 AUCKLAND ACHIEVERS Kiwis honour industry’s elite MOONEE NO MORE Curtains close on Valley conference BARNESY’S BEST NQ bus industry legend retires WWW.TRADEBUSES.COM.AU DECKER Hong Kong harbours higher desire TRADEBUSES.COM.AU THE BUS YOU WANT IS NOW EASIER TO FIND ABC-HH-5192704-CS-299-XCC REDUCED $145,000 + GST 2003 Scania K94 TO • 48 lap sash belted cloth reclining seats • Opticruise transmission Contact Justin Cannon • 9 litre engine • 12.5 metre length • DVD / TV and toilet equipped 13 22 59 • Air conditioned [email protected] $80,000 + GST REDUCED 1994 Scania K113 2008 ANKAI 3 AXLE TO $160,000 + GST • 61 lap sash belted cloth reclining seats • 50 lap sash belted leather reclining seats • 14.5 metre length • Allison automatic transmission • Cummins ISM engine • 11 ltr engine • 13.7 metre length • Air conditioned • TV / DVD & toilet equipped • 10 sp splitter transmission • Nippon Denso air conditioning • Toilet equipped • DVD / Radio / PA / Tape Player ABC-HH-5165311-TS-325-X 82 AUSTRALASIAN BUS & COACH | September 2014 busnews.com.au WANT TO ADVERTISE? CALL 03 9567 4154 Bookings for next issue close on October 9, 2014 RELOCATION SALE - WE'D RATHER SELL IT THAN MOVE IT - SO CALL FOR A DEAL!! 1999 Hino RG230 School Bus 1994 Scania K113 2007 BCI Cruiser 9 •230HP Engine • 6 Speed manual • 12.5m length 53 bench seats in 2-3 layout • ISB Engine • Allison Auto Transmission • Great condition and smart looking body • 43 seats with 3 point lap sash seat belts 2009 model • 49 APM reclining leather seats with 3-pt lap sash seat belts • ZF Automatic trans. -

GETTING Homesafely Anewapproach.Com.Au

GETTING Home SAFELY Labor’s pLAN TO MAKE TRAIN TRAVEL SAFER ON FRIDAY AND SATURDAY NIGHTS Labor understands that the people of NSW deserve safe, reliable and comfortable public transport. As part of providing a public transport service that meets community needs a Foley Government will do all it can to make travelling on public transport safer. That’s why Labor will: • Re-introduce Guardian train services on Friday and Saturday nights; and • Run all-night train services from Kings Cross to Town Hall and Central Stations. Feeling safe and having confidence in the security on our trains is a major factor for people choosing whether or not to use the rail network, especially for women, parents with children, and older and other vulnerable people. The NRMA’s Seeing Red on Rail reported personal security as the second most pressing issue for over 11,000 thousand commuters. 38% of commuters in this survey said that they do not feel safe at certain times of the day. The Sydney Trains network includes 12 lines, 176 stations and many interchanges. NSW TrainLink network includes 5 intercity lines and over 130 stations. It is a large area to cover. Knowing that there is assistance if other passengers are being anti-social, violent or abusive – especially at night, can increase the numbers of people using public transport as well as improve security. Under the Baird Liberal Government, security on the rail network has been cut. When the Liberals and Nationals came to government in 2011 there were 600 dedicated transit officers for trains and 300 commuter police attached to local area commands. -

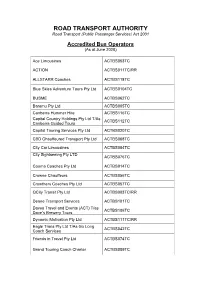

Accredited Bus Operators (As at June 2020)

ROAD TRANSPORT AUTHORITY Road Transport (Public Passenger Services) Act 2001 Accredited Bus Operators (As at June 2020) Ace Limousines ACTBS053TC ACTION ACTBS011TC/RR ALLSTARR Coaches ACTBS118TC Blue Skies Adventure Tours Pty Ltd ACTBS0104TC BUSME ACTBS062TC Baromu Pty Ltd ACTBS005TC Canberra Hummer Hire ACTBS116TC Capital Country Holdings Pty Ltd T/As ACTBS112TC Canberra Guided Tours Capital Touring Services Pty Ltd ACTBS020TC CBD Chauffeured Transport Pty Ltd ACTBS068TC City Car Limousines ACTBS084TC City Sightseeing Pty LTD ACTBS076TC Cooma Coaches Pty Ltd ACTBS014TC Crowne Chauffeurs ACTBS056TC Crowthers Coaches Pty Ltd ACTBS057TC QCity Transit Pty Ltd ACTBS003TC/RR Deane Transport Services ACTBS101TC Daves Travel and Events (ACT) T/as ACTBS106TC Dave’s Brewery Tours Dynamic Motivation Pty Ltd ACTBS111TC/RR Eagle Trans Pty Ltd T/As Go Long ACTBS042TC Coach Services Friends in Travel Pty Ltd ACTBS074TC Grand Touring Coach Charter ACTBS009TC Greyhound Australia Pty Ltd ACTBS034TC Horizon Coach Charters ACTBS081TC Hummingbird Charters T/As ACTBS071TC Snow Alliance Keir’s Group Of Companies Pty Ltd ACTBS015TC Kennedys Bus & Coach ACTBS078TC KMET Transport Services Pty Ltd ACTBS070TC T/As Roadcoach Lanaad Pty Ltd ATF DM Charters ACTBS117TC Trust Makeham’s Coaches ACTBS026TC Marulan Truck & Bus Pty Ltd T/as ACTBS121TC Marulan Coaches Marshall’s Bus & Coach company ACTBS036TC PTY Ltd Michael Minter T/as Voorpret ACTBS124TC Monaro Coaches ACTBS022TC Moonlight Stretch Limo Pty Ltd ACTBS085TC Murrays Australia PTY LTD ACTBS010TC North Sydney -

Appendix C Consultation

Environmental Impact Statement Wellington Solar Farm APPENDIX C CONSULTATION 17‐076 Final v1.1 C‐I Community Consultation Plan WELLINGTON SOLAR FARM NOVEMBER 2017 www.nghenvironmental.com.au e [email protected] Sydney Region Canberra ‐ NSW SE & ACT Wagga Wagga ‐ Riverina and Western NSW 18/21 mary st 17/27 yallourn st (po box 62) suite 1, 39 fitzmaurice st (po box 5464) surry hills nsw 2010 (t 02 8202 8333) fyshwick act 2609 (t 02 6280 5053) wagga wagga nsw 2650 (t 02 6971 9696) Newcastle ‐ Hunter and North Coast Bega ‐ ACT and South East NSW Bathurst ‐ Central West and Orana 7/11 union st suite 1, 216 carp st (po box 470) 35 morrisset st (po box 434) newcastle west nsw 2302 (t 02 4929 2301) bega nsw 2550 (t 02 6492 8333) bathurst nsw 2795 (t 02 6331 4541) Document Verification Project Title: CCP ‐ Wellington Solar Farm Project Number: 17‐076 Project File Name: Wellington CCP Final v1.1 Revision Date Prepared by (name) Reviewed by (name) Approved by (name) Draft V1 20/04/17 Jenny Walsh Nick Graham‐Higgs Jenny Walsh Final v1 19/10/17 Zoe Quaas Brooke Marshall Brooke Marshall Final v1 06/11/17 Jane Blomfield Minor changes NGH Environmental prints all documents on environmentally sustainable paper including paper made from bagasse (a by‐ product of sugar production) or recycled paper. NGH Environmental Pty Ltd (ACN: 124 444 622. ABN: 31 124 444 622) and NGH Environmental (Heritage) Pty Ltd (ACN: 603 938 549. ABN: 62 603 938 549) are part of the NGH Environmental Group of Companies. -

Australia ‒ a Travel Report by Patrick Klich

Australia ‒ A Travel Report by Patrick Klich Spending 10 months in Australia as a student at the Australian National University may be one of the best things you are ever going to do. Great adventures are waiting. For me it was a time of studying hard, socializing a lot and meeting many people from different cultures (hey – I got a Chinese name: Xiongxiong, which means something like “Little bear”), doing a lot of sports and thus losing weight (running, running and more running – hint: IB), learning about the country and learning more about myself. First I am going to explain why I wanted to study at the ANU. Second I am going to say something about Australia, Canberra, the Australian National University and the Australian culture. Then I am going to say something about getting ready for Australia. I will include some useful hints about “living in Canberra”. I felt the need to go somewhere far away for a long time in order totry something new, something different, something challenging before attending the course “Australian Culture”. Since Australia is so far away and I almost did not know anything about the continent, I was ready and eager to learn more about Australia. At some point, Ms. McIlwaine mentioned that one student will get the opportunity to study at the Australian National University in Canberra. Improving and perfecting my English, studying at a foreign “elite” University, meeting new people, learning about the Australian Culture were some of the goals I wanted to accomplish. Australia Australia has beautiful landscapes, unique animals, a superb climate, tasty food and much more. -

Integrated Transport Strategy

Queanbeyan-Palerang Regional Council 09-Jun-2020 Integrated Transport Strategy Final Report P:\CBR\60544563\8. Issued Docs\8.1 Reports\ITS\DOCS\60544563 QPRC ITS FINAL 9 June 2020.docx Revision 5 – 09-Jun-2020 Prepared for – Queanbeyan-Palerang Regional Council – ABN: 95 933 070 982 AECOM Integrated Transport Strategy – Final Report Integrated Transport Strategy Final Report Client: Queanbeyan-Palerang Regional Council ABN: 95 933 070 982 Prepared by AECOM Australia Pty Ltd Civic Quarter, Level 4, 68 Northbourne Avenue, GPO Box 1942 ACT 2601, Canberra ACT 2601, Australia T +61 2 6100 0551 www.aecom.com ABN 20 093 846 925 09-Jun-2020 Job No.: 6054 4563 AECOM in Australia and New Zealand is certified to ISO9001, ISO14001 AS/NZS4801 and OHSAS18001. © AECOM Australia Pty Ltd (AECOM). All rights reserved. AECOM has prepared this document for the sole use of the Client and for a specific purpose, each as expressly stated in the document. No other party should rely on this document without the prior written consent of AECOM. AECOM undertakes no duty, nor accepts any responsibility, to any third party who may rely upon or use this document. This document has been prepared based on the Client’s description of its requirements and AECOM’s experience, having regard to assumptions that AECOM can reasonably be expected to make in accordance with sound professional principles. AECOM may also have relied upon information provided by the Client and other third parties to prepare this document, some of which may not have been verified. Subject to the above conditions, this document may be transmitted, reproduced or disseminated only in its entirety. -

NSW Trains Annual Report 2019-20

NSW Trains Annual Report Volume 1 • 2019–20 NSW Trains (trading as NSW TrainLink) 470 Pitt Street Haymarket NSW 2000 Monday to Friday 8.30 am to 5.30 pm Ph: (02) 8202 2200 transportnsw.info or call 131 500 (24 hours, 7 days a week) Follow us on Twitter @TrainLinkNorth @TrainLinkSouth @TrainLinkWest External design services were used to produce this report. The total external costs associated with the production of this report were approximately $7500. This Annual Report can be accessed on the Transport NSW website transport.nsw.gov.au. ISSN: 2204‑101X ©2020 NSW Trains Unless otherwise stated, all images (including photography, background images, icons and illustrations) are the property of NSW Trains. Users are welcome to copy, reproduce and distribute the information contained in this report for non–commercial purposes only, provided acknowledgement is given to NSW Trains as the source. Letter to Ministers The Hon Andrew Constance MP Minister for Transport and Roads Parliament House Macquarie Street Sydney NSW 2000 The Hon Paul Toole MP Minister for Regional Transport and Roads Parliament House Macquarie Street Sydney NSW 2000 Dear Ministers I am pleased to submit for presentation to Parliament the Annual Report for NSW Trains for the financial year ended 30 June 2020. The Annual Report has been prepared in accordance with the Annual Reports (Statutory Bodies) Act 1984 and the Annual Reports (Statutory Bodies) Regulation 2015. Yours sincerely Pete Allaway Chief Executive NSW Trains Letter to Minister • iii Foreword 2 From the Chief Executive -

NSW Trainlink Regional Train and Coach Services Connect More Than 365 Destinations in NSW, ACT, Victoria and Queensland

Go directly to the timetable Dubbo Tomingley Peak Hill Alectown Central West Euabalong West Condobolin Parkes Orange Town Forbes Euabalong Bathurst Cudal Central Tablelands Lake Cargelligo Canowindra Sydney (Central) Tullibigeal Campbelltown Ungarie Wollongong Cowra Mittagong Lower West Grenfell Dapto West Wyalong Bowral BurrawangRobertson Koorawatha Albion Park Wyalong Moss Vale Bendick Murrell Barmedman Southern Tablelands Illawarra Bundanoon Young Exeter Goulburn Harden Yass Junction Gunning Griffith Yenda Binya BarellanArdlethanBeckomAriah Park Temora Stockinbingal Wallendbeen Leeton Town Cootamundra Galong Sunraysia Yanco BinalongBowning Yass Town ACT Tarago Muttama Harden Town TASMAN SEA Whitton BurongaEuston BalranaldHay Carrathool Darlington Leeton NarranderaGrong GrongMatong Ganmain Coolamon Junee Coolac Murrumbateman turnoff Point Canberra Queanbeyan Gundagai Bungendore Jervis Bay Mildura Canberra Civic Tumut Queanbeyan Bus Interchange NEW SOUTH WALES Tumblong Adelong Robinvale Jerilderie Urana Lockhart Wagga Wondalga Canberra John James Hospital Wagga Batlow VICTORIA Deniliquin Blighty Finley Berrigan Riverina Canberra Hospital The Rock Laurel Hill Batemans Bay NEW SOUTH WALES Michelago Mathoura Tocumwal Henty Tumbarumba MulwalaCorowa Howlong Culcairn Snowy Mountains South Coast Moama Barooga Bredbo Albury Echuca South West Slopes Cooma Wangaratta Berridale Cobram Nimmitabel Bemboka Yarrawonga Benalla Jindabyne Bega Dalgety Wolumla Merimbula VICTORIA Bibbenluke Pambula Seymour Bombala Eden Twofold Bay Broadmeadows Melbourne (Southern Cross) Port Phillip Bay BASS STRAIT Effective from 25 October 2020 Copyright © 2020 Transport for NSW Your Regional train and coach timetable NSW TrainLink Regional train and coach services connect more than 365 destinations in NSW, ACT, Victoria and Queensland. How to use this timetable This timetable provides a snapshot of service information in 24-hour time (e.g. 5am = 05:00, 5pm = 17:00). Information contained in this timetable is subject to change without notice. -

Machine Printed Tickets (Sept 2013)

1.26N Machine printed tickets (Sept 2013) Ticket Issue Machine (TIM) The following relates to these machines initially used on government buses in NSW from 1951. TIM Model 3, 1d-4/11d. Imported from UK via TIM agents in Bentleigh Vic. Whole ticket printed in purple on strip, value dialled by driver or queue conductor1, includes route and section (001-009) for bus or day/hour code (11-99) for queue conductor. The code at left signifies O= ordinary, F= combined ferry ticket, 2/W= child’s two way ticket, C= concession, T= transfer ticket, R= return ticket. They were also used by the following private operators (bold indicates examples seen): Bosnjak Edensor Park, Blue & Red Buses Murwillumbah, Mylon’s Busways Albury-Wodonga, Fogg’s Bus Service Singleton. West Bankstown Bus Service is known to have used both titled and untitled2 TIMs- see the examples illustrated. Some operators used the generic wording “Passenger Services”: see the chapter on OPA generic tickets for details. In all cases the machine number (indicated in the illustration) should tie a machine to an operator. West Bankstown Bus Service is an example. Ultimate machine (Bell Punch)3 The following relates to the first use of these machines by the government in 1949: 5 value machine issuing pre-printed tickets, could be issued in multiples. Imported from Bell Punch (UK) via Australian Agents Control Systems A/Asia Pty Ltd. Day/hour code & number printed in black within base of ticket. Not transferable details on back. Tickets printed in black on colour with coloured value and issued in reels. -

Monday 8 to Sunday 14 March 2021

Monday 8 to Sunday 14 March 2021 Bussing Line Day(s) affected Reference: STN or TAA View timetable Select the line for more info Mobile devices must be connected via VPN WD WE Monday – Thursday STN 0398 Weekend STN 0419 No planned trackwork Central – Circular Quay No planned trackwork Monday – Thursday STN 0398 Weekend STN 0419 Monday – Thursday STN 0398 Weekend STN 0419 Weekend STN 0419 No planned trackwork No planned trackwork Tuesday – Thursday STN 0407 No planned trackwork No planned trackwork Monday – Thursday STN 0398 Weekend STN 0419 Weekend STN 0419 Saturday STN 0419 Weekend Weekend STN 0419 + TAA 0003 No planned trackwork No planned trackwork Trackwork Bussing Map Special Events extract Key: Next week’s trackwork Feedback form Click to view the bus timetable Scope of work: Configurations 9 + 3 Bus timetable is not available Please use this guide to advise Sydney Metro, Sydney Trains and NSW TrainLink Intercity customers of trackwork affecting their journey. Please make this guide available to all staff at your location. Easy access alternate transport Staff should contact ROC Customer & Information on 7 7039 if alternate transport is required for customers requiring easy access transport when travelling through areas affected by trackwork. Trackwork Altered transport arrangements Sydney Metro, Sydney Trains and NSW TrainLink Intercity services Monday 8 to Sunday 14 Month Monday 8 to Thursday 11 March Nightly from 21:50 until 02:00 Reference: STN 0398 Work: Flying Junctions – Hornsby • No trackwork scheduled on the metro, but trackwork on the T1 North Shore Line may affect how customers travel. • Customers travelling to the City should change at Epping, not Chatswood, for a direct train via the T9 Northern Line.