NAHSE 50-1.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bad Cops: a Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers Author(s): James J. Fyfe ; Robert Kane Document No.: 215795 Date Received: September 2006 Award Number: 96-IJ-CX-0053 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers James J. Fyfe John Jay College of Criminal Justice and New York City Police Department Robert Kane American University Final Version Submitted to the United States Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice February 2005 This project was supported by Grant No. 1996-IJ-CX-0053 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of views in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. -

Closed Residency Programs - Printable Format

Closed Residency Programs - Printable Format Affinity Medical Center Emergency Medicine - AOA - 126165 Family Medicine - AOA - 127871 Internal Medicine - AOA - 127872 Obstetrics & Gynecology (1980-1994) - AOA - 127873 Obstetrics & Gynecology (1995-1999) - AOA - 126168 Pediatrics - AOA - 127877 Affinity Medical Center - Doctors Hospital of Stark County Family Medicine - AOA - 126166 Family Medicine - AOA - 341474 Orthopaedic Surgery - AOA - 126170 Otolaryngology - AOA - 126169 Surgery - AOA - 126171 Traditional Rotating Internship - AOA - 125275 Cabrini Medical Center Clinical Clerkship - - [Not Yet Identified] Internal Medicine - ACGME - 1403531266 Internal Medicine / Cardiovascular Disease - ACGME - 1413531114 Internal Medicine / Gastroenterology - ACGME - 1443531098 Internal Medicine / Hematology & Medical Oncology - ACGME - 1553532048 Internal Medicine / Infectious Diesease - ACGME - 1463531097 Internal Medicine / Pulmonary Disease - ACGME - 1493531096 Internal Medicine / Rheumatology - ACGME - 1503531068 Psychiatry - ACGME - 4003531137 Surgery - ACGME - 4403521209 Caritas Healthcare, Inc. - Mary Immaculate Hospital Family Medicine - ACGME - 1203521420 Internal Medicine - ACGME - 1403522267 Internal Medicine / Gastroenterology - ACGME - 1443522052 Internal Medicine / Geriatric Medicine - ACGME - 1513531124 Internal Medicine / Infectious Diesease - ACGME - 1463522041 Internal Medicine / Pulmonary Disease - ACGME - 1493522047 Closed Residency Programs - Printable Format Caritas Healthcare, Inc. - St. John's Queens Hospital Clinical Clerkship -

Tables for Web Version of Letter NYC Independent Budget Office - Health and Social Services Printed 6/5/01 at 1:24 PM

Attachment B Contracting Agencies (based on FY 2000 Contracts) HIV HIV Ryan White Prevention Ryan White Prevention Agency Services Project Agency Services Project African Services Committee, Inc * * HHC Harlem Hospital Center * AIDS Center of Queens County, Inc * HHC Jacobi Medical Center * AIDS Day Services Association of New York State, Inc * HHC Kings County Hospital Center * AIDS Service Center of Lower Manhattan, Inc * * HHC North Central Bronx Hospital * AIDS Treatment Data Network, Inc * HHC Queens Hospital Center * Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University * HHC Woodhull Medical & Mental Health Center * Alianza Dominicana, Inc * Hispanic AIDS Forum, Inc * * Ambulatory Care * HIV Law Project, Inc * American Indian Community House, Inc * Hudson Planning Group, Inc * American Red Cross * Institute for Community Living, Inc * Argus Community, Inc * Institute for Urban Family Health, Inc * Asian & Pacific Islander Coalition on HIV/AIDS, Inc * * Interfaith Medical Center * Assessment and Referral Team for AIDS * Iris House, A Center For Women Living With HIV, Inc * Association for Drug Abuse Prevention and Treatment, Inc * Jewish Board of Family & Children's Services, Inc * Bailey House, Inc * Jewish Guild for the Blind * Banana Kelly Community Improvement Association * Latino Commission on AIDS, Inc * Bedford Stuyvesant Community Legal Services Corporation * Legal Action Center of the City of New York, Inc * Betances Health Unit, Inc * Legal Aid Society * Beth Abraham Health Services * Legal Support Unit of Legal Services -

County of Cook: Milestones in Health Care

1835 Nearly two County of Cook: 1840 Centuries of 1850 1860 Health Services to A DISTINGUISHED HERITAGE OF HEALTH 1870 the Community 1880 1890 1900 1910 Milestones in Health Care 1920 1930 John H. Stroger, Jr. President, Introduction1940 Cook County Board of Commissioners In 1835, four years after Cook County Government was incorporated, the first health services,The Public Alms House for the poor, was estab- lished. Now, 165 years later, this has evolved into1 9the5 Cook0 County Bureau of Health Services, an innovative, cost-efficient system of integrated healthcare.Today, it is the second largest division of Cook County Government and one of the largest public health systems in 1the960 country, caring for more than 1.5 million people every year. From that day when the County first became responsible for ministering to the sick poor, we have taken our charge very seriously. And, as you’ll 1970 see in this exhibit, we have attracted many of the pioneers of medicine whose work earned Cook County Hospital and Provident Hospital reputations for professional excellence around the world. 1980 T h extr is e delivery of healthcare services and it celebrates the vital role the Cook 1990 aordinaryxh role that Cook County Government has played in the County Bureau of Healthibit recogn Se d istinguished history. 2000 T h time andis e effort, and those that continue to work today to meet the izes the milestones that so richly represent the healthcare needsxhibit of also the honorsresi the healthcare providers who have given of their pr 2002 who continueofessi to work tirelessly to ensure that healthcare is available and accessib apprec onals w le to anyone, regardless of their ability to pay, we extend our deep iati rv ho have been a par ices plays as the ar on and our g dents of Cook County.To all the healthcare ratitud t of our d ch e f itect of such a or a job well done. -

David Norman Dinkins Served As NYS Assemblyman, President of The

David Norman Dinkins served as NYS Assemblyman, President of the NYC Board of Elections, City Clerk, and Manhattan Borough President, before being elected 106th Mayor of the City of New York in 1989. As the first (and only) African American Mayor of NYC, major successes of note under his administration include: “Safe Streets, Safe City: Cops and Kids”; the revitalization of Times Square as we have come to know it; an unprecedented agreement keeping the US Open Tennis Championships in New York City for 99 years – a contract that continues to bring more financial influx to New York City than the Yankees, Mets, Knicks and Rangers COMBINED – comparable to having the Super Bowl in New York for two weeks every year! The Dinkins administration also created Fashion Week, Restaurant Week, and Broadway on Broadway, which have all continued to thrive for decades, attracting international attention and tremendous revenue to the city each year. Mayor Dinkins joined Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA) as a Professor in the Practice of Urban Public Policy in 1994. He has hosted the David N. Dinkins Leadership and Public Policy Forum for 20 years, which welcomed Congressman John Lewis as Keynote Speaker in 2017. 2015 was a notable year for Mayor Dinkins: the landmarked, Centre Street hub of New York City Government was renamed as the David N. Dinkins Municipal Building; the David N. Dinkins Professorship Chair in the Practice of Urban and Public Affairs at SIPA (which was established in 2003) announced its inaugural professor, Michael A Nutter, 98th Mayor of Philadelphia; and the Columbia University Libraries and Rare Books opened the David N. -

Raymond Howard Curry, MD, FACP, FACH CURRICULUM VITAE

Raymond Howard Curry, MD, FACP, FACH CURRICULUM VITAE APRIL 2020 WORK ADDRESS University of Illinois at Chicago (312) 996-1200 (administrative) 131 College of Medicine West Tower e-mail: [email protected] Mail Code 784 1853 West Polk Street Chicago, IL 60612-7333 CURRENT POSITIONS Senior Associate Dean for Educational Affairs University of Illinois College of Medicine Professor of Medicine and Medical Education University of Illinois at Chicago Physician/Surgeon University of Illinois Hospital and Health System, Chicago Associate Member of the Faculty, Graduate College University of Illinois at Chicago Faculty Fellow, Honors College University of Illinois at Chicago LICENSURE AND CERTIFICATION 1982 Diplomate, National Board of Medical Examiners (#263713) 1983- Licensed to practice medicine, State of Illinois (#036-067116) 1985- Diplomate, American Board of Internal Medicine (#101674) 1992-2002 Diplomate in Geriatric Medicine, American Board of Internal Medicine (#101674) 1 RAYMOND H. CURRY EDUCATION 1977 AB, University of Kentucky, Lexington University Honors Program Mary Sue Coleman, honors thesis advisor (biochemistry) 1982 MD, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis POSTGRADUATE TRAINING 1982-1985 Resident in Internal Medicine, McGaw Medical Center of Northwestern University, Chicago FACULTY APPOINTMENTS 1985-1989; Instructor in Clinical Medicine, Northwestern University Medical School 1989-1996; Assistant Professor of Medicine, Northwestern University Medical School 1995-1996; Assistant Professor of Medical Education, Northwestern University Medical School 1996-2002; Associate Professor of Medicine and Medical Education, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine 2002-2014 Professor of Medicine and Medical Education, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine ________ 2015-2019 Visiting Professor of Clinical Medicine and Medical Education, University of Illinois at Chicago 2018- Faculty Fellow, University of Illinois at Chicago Honors College 2019- Adjunct Professor of Medicine, M. -

Syracuse Manuscript Are Those of the Authors and Do Not Necessarily Represent the Opinions of Its Editors Or the Policies of Syracuse University

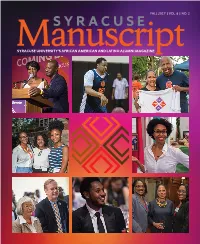

FALL 2017 | VOL. 6 | NO. 2 SYRACUSE ManuscriptSYRACUSE UNIVERSITY’S AFRICAN AMERICAN AND LATINO ALUMNI MAGAZINE CONTENTS ON THE COVER: Left to right, from top: Cheryl Wills ’89 and Taye Diggs ’93; Lazarus Sims ’96; Lt. Col. Pia W. Rogers ’98, G’01, L’01 and Dr. Akima H. Rogers ’94; Amber Hunter ’19, Nerys Castillo-Santana ’19, and Nordia Mullings ’19; Demaris Mercado ’92; Dr. Ruth Chen and Chancellor Kent Syverud; Carmelo Anthony; Darlene Harris ’84 and Debbie Harris ’84 with Soledad O’Brien CONTENTS Contents From the ’Cuse ..........................................................................2 Celebrate Inspire Empower! CBT 2017 ........................3 Chancellor’s Citation Recipients .......................................8 3 Celebrity Basketball Classic............................................ 12 BCCE Marks 40 Years ....................................................... 13 OTHC Milestones ............................................................... 14 13 OTHC Donor List ............................................................17 SU Responds to Natural Disasters ..............................21 Latino/Hispanic Heritage Month ................................22 Anthony Reflects on SU Experience .........................23 Brian Konkol Installed as Dean of Hendricks Chapel ............................................................23 21 26 Diversity and Inclusion Update ...................................24 8 Knight Makes SU History .............................................25 La Casita Celebrates Caribbean Music .....................26 -

The Politics of Charter School Growth and Sustainability in Harlem

REGIMES, REFORM, AND RACE: THE POLITICS OF CHARTER SCHOOL GROWTH AND SUSTAINABILITY IN HARLEM by Basil A. Smikle Jr. Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 © 2019 Basil A. Smikle Jr. All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT REGIMES, REFORM, AND RACE: THE POLITICS OF CHARTER SCHOOL GROWTH AND SUSTAINABILITY IN HARLEM By Basil A. Smikle Jr. The complex and thorny relationship betWeen school-district leaders, sub-city political and community figures and teachers’ unions on the subject of charter schools- an interaction fraught with racially charged language and tactics steeped in civil rights-era mobilization - elicits skepticism about the motives of education reformers and their vieW of minority populations. In this study I unpack the local politics around tacit and overt racial appeals in support of NeW York City charter schools with particular attention to Harlem, NeW York and periods when the sustainability of these schools, and long-term education reforms, were endangered by changes in the political and legislative landscape. This dissertation ansWers tWo key questions: How did the Bloomberg-era governing coalition and charter advocates in NeW York City use their political influence and resources to expand and sustain charter schools as a sector; and how does a community with strong historic and cultural narratives around race, education and political activism, respond to attempts to enshrine externally organized school reforms? To ansWer these questions, I employ a case study analysis and rely on Regime Theory to tell the story of the Mayoral administration of Michael Bloomberg and the cadre of charter leaders, philanthropies and wealthy donors whose collective activity created a climate for growth of the sector. -

LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTION Paying Tribute to the Life and Accomplishments of Dr

LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTION paying tribute to the life and accomplishments of Dr. Daniel Hale Williams, surgical pioneer of open heart surgery and its sterilization procedures WHEREAS, With February being Black History Month, it is a time to reflect on the struggles and victories of African Americans throughout our country's history and to recognize their numerous valuable contrib- utions to society; and WHEREAS, Daniel Hale Williams was born on January 18, 1856, in Holli- daysburg, Pennsylvania; he was the fifth of seven children born to Daniel and Sarah Williams; and WHEREAS, Daniel Hale Williams's father was a barber and moved the family to Annapolis, Maryland, but died shortly thereafter of tuberculo- sis; Daniel's mother realized she could not manage the entire family and sent some of the children to live with relatives; Daniel was apprenticed to a shoemaker in Baltimore, but soon moved away to join his mother who had relocated to Rockford, Illinois; and WHEREAS, Daniel Hale Williams later moved to Edgerton, Wisconsin, where he joined his sister and opened his own barber shop; after moving to nearby Janesville, he became fascinated with a local physician and decided to follow his path; and WHEREAS, After following the example of his older brother studying law for a short time, Daniel Hale Williams began working as an apprentice to the physician, Dr. Henry Palmer for two years and in 1880, entered what is now known as Northwestern University Medical School; after graduation from Northwestern in 1883, he opened his own medical office in Chicago, Illinois; and WHEREAS, Because of primitive social and medical circumstances exist- ing in that era, much of Dr. -

Daniel Hale Williams House

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (Rev. 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Illinois COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Cook INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY DATE (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) mmmm C OMMON: AND/OR HISTORIC: Dr. Daniel Hale Williams House STREET AND NUMBER: 445 East 42nd Street CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT: Chicago First STATE COUNTY: Illinois Cook jQ31 CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC D District g Building Public Public Acquisition: [X] Occupied Yes: O Restricted D Site Q Structure Private [| In Process [I Unoccupied Both [ | Being Considered | | Unrestricted D Object I I Preservation work in progress S No PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) [ I Agricultural [ I Government D Pork I I Transportation [ | Comments [ | Commercial [ | Industrial [X) Private Residence D Othe [ | Educational n Military [ I Religious I I Entertainment O Museum d] Scientific OWNER'S NAME: Mr. Albert Morris STREET AND NUMBER: 445 East 42nd Street CITY OR TOWN: CODF Chicago linens 17 COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Cook County Recorder of Deeds - County Building 9 2 STREET AND NUMBER: o 118 North Clark Street C1TY OR TOWN: Chicago_________________ Imois 17 TITLE OF SURVEY: None known DATE OF SURVEY: Federal State Q County Local DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: (Check One) Excellent d Good [X| Fair d Deteriorated d Ruins d Unexposed CONDITION (minor) < Check One) (Check One) 13 Altered d Unaltered Moved S Original Site DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (if known) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Dr. Williams residence at 445 East 42nd Street is located on the south side of 42nd Street, facing north. -

The Healthcare Experts

FOR NEWS for Crain’s Health Pulse, contact reporter CRAIN’S HEALTH Crain’s Health Pulse is Gale Scott at available Monday through (212) 210-0746 Friday by 6:00 a.m. A product or [email protected] of Crain’s New York Business. Copyright 2007. Reproduction or Barbara Benson in any form is prohibited. at (718) 855-3304 For customer service, call or [email protected] pulseA daily newsletter on the business of health care (888) 909-9111. Wednesday, August 8, 2007 TODAY’S NEWS Dupe CINs a longstanding problem PREZ, CEO & CRO GADE Dr. Ronald Gade is a busy man. At the The attorney general’s announce- what they suspect are duplicate CINs, request of the state Department of Health, ment this week about recovering $7 mil- and the people aren’t taken off the he agreed to take the restructuring officer lion from HealthFirst and now-defunct rolls,” says Robert Belfort, a partner at job at North General Hospital. But he will Partners In Health because of duplicate Manatt Phelps & Phillips and counsel to continue in his role as president and chief client ID numbers for some Medicaid the Prepaid Health Service Plan Coali- executive of Cabrini Medical Center, and Family Health Plus beneficiaries did tion, which is composed of Medicaid according to a hospital spokesman. “He not surprise people in the industry. plans. has unequivocally communicated his com- Medicaid managed care plans have Because contracts place time limits mitment to Cabrini and to ensuring the suc- been begging the state for years to fix on retroactive adjustment, the PHSPs cess of our restructuring plan,” he says. -

Teaching for Black Lives, Have Been Prepared for Teachers to Use During the Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action

These articles and sample teaching activities from the book, Teaching for Black Lives, have been prepared for teachers to use during the Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action. www.teachingforblacklives.com What is Rethinking Schools? What else does Rethinking Schools do? Rethinking Schools a nonprofit organization that • We co-direct the Zinn Education Project publishes a quarterly magazine, books, and digital www.zinnedproject.org content to promote social and racial justice teaching • We co-sponsor social justice teacher events and pro-child, pro-teacher educational policies. We across the country. are strong defenders of public schools and work hard • We frequently present at local, state and national to improve them so that they do a better job serving NEA conferences and at other teaching for social all students. justice gatherings. • We develop and promote curriculum on pressing Who started Rethinking Schools? issues such as racism and antiracist teaching, Early career educators! But that was back in 1986 so immigration, and support for Black Lives Matter, the founders are not so “early” in their careers any Standing Rock, climate justice, and other social more. However, early career educators remain editors justice movements. and leaders of Rethinking Schools and many write for our magazine. Why is this important? Brazilian educator Paulo Freire wrote that teachers Who runs Rethinking Schools? should attempt to “live part of their dreams within Teachers. We have an editorial collective of practicing their educational space.” Rethinking Schools believes and retired educators from several states and have schools can be greenhouses of democracy and that published articles by teachers from many states and a classrooms can be places of hope, where students and several countries.