Ny Business Law Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(212) 792-0300 [email protected]

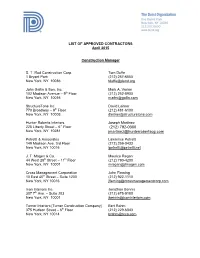

LIST OF APPROVED CONTRACTORS April 2015 Construction Manager S. T. Rud Construction Corp. Tom Duffe 1 Bryant Park (212) 257-6550 New York, NY 10036 [email protected] John Gallin & Son, Inc. Mark A. Varian 102 Madison Avenue – 9th Floor (212) 252-8900 New York, NY 10016 [email protected] StructureTone Inc. David Leitner 770 Broadway – 9th Floor (212) 481-6100 New York, NY 10003 [email protected] Hunter Roberts Interiors Joseph Martinez 225 Liberty Street – 6th Floor (212) 792-0300 New York, NY 10281 [email protected] Petretti & Associates Lawrence Petretti 149 Madison Ave, 3rd Floor (212) 259-0433 New York, NY 10016 [email protected] J. T. Magen & Co. Maurice Regan 44 West 28th Street – 11th Floor (212) 790-4200 New York, NY 10001 [email protected] Cross Management Corporation John Fleming 10 East 40th Street – Suite 1200 (212) 922-1110 New York, NY 10016 [email protected] Icon Interiors Inc. Jonathan Bennis 307 7th Ave. – Suite 203 (212) 675-9180 New York, NY 10001 [email protected] Turner Interiors [Turner Construction Company] Bert Rahm 375 Hudson Street – 6th Floor (212) 229-6043 New York, NY 10014 [email protected] James E. Fitzgerald, Inc. John Fitzgerald 252 West 38th Street, 10th Floor (212) 930-3030 New York, NY 10018 [email protected] Clune Construction Company Tommy Dwyer The Chrysler Center (646) 569-3220 405 Lexington Avenue – 27th Floor [email protected] New York, NY 10174 Electrical Contractors Schlesinger Electrical Contractors, Inc. Alan Burczyk 664 Bergen St. (718) 636-3944 Brooklyn, NY 11238 [email protected] Star Delta Electric LLC Randy D’Amico 17 Battery Pl #203 (212) 943-5527 New York, NY 10004 [email protected] Fred Geller Electrical, Inc. -

Annual Procurement Report Fiscal Year 2016 – 2017

Andrew M. Cuomo, Governor RuthAnne Visnauskas, Commissioner/CEO Annual Procurement Report Fiscal Year 2016 – 2017 For the Period Commencing November 1, 2016 and Ending October 31, 20171 January 25, 2018 NEW YORK STATE HOUSING FINANCE AGENCY STATE OF NEW YORK MORTGAGE AGENCY NEW YORK STATE AFFORDABLE HOUSING CORPORATION STATE OF NEW YORK MUNICIPAL BOND BANK AGENCY TOBACCO SETTLEMENT FINANCING CORPORATION 641 Lexington Avenue Ι New York, NY 10022 212-688-4000 Ι www.nyshcr.org 1 Although AHC’s fiscal year runs from April 1st through March 31st, for purposes of this consolidated Report, AHC’s procurement activity is reported using a November 1, 2016 – October 31, 2017 period, which conforms to the fiscal period shared by four of the five Agencies. NEW YORK STATE HOUSING FINANCE AGENCY STATE OF NEW YORK MORTGAGE AGENCY NEW YORK STATE AFFORDABLE HOUSING CORPORATION STATE OF NEW YORK MUNICIPAL BOND BANK AGENCY TOBACCO SETTLEMENT FINANCING CORPORATION Annual Procurement Report For the Period Commencing November 1, 2016 and Ending October 31, 2017 Annual Procurement Report Index SECTION TAB Agencies’ Listing of Pre-qualified Panels…………………………..……………………………….1 Summary of the Agencies’ Procurement Activities………………………………………..………. 2 Agencies’ Consolidated Procurement and Contract Guidelines (Effective as of December 15, 2005, Revised as of September 12, 2013)…………………………………....3 Explanation of the Agencies’ Procurement and Contract Guidelines………………………………4 TAB 1 Agencies’ Listing of Pre-qualified Panels TAB 1 Agencies’ Listing of Pre-Qualified Panels Arbitrage Rebate Services Pre-qualified Panel of the: ▸ New York State Housing Finance Agency - BLX Group LLC - Hawkins, Delafield & Wood LLP - Omnicap Group LLC ▸ State of New York Mortgage Agency ▸ State of New York Municipal Bond Bank Agency ▸ Tobacco Settlement Financing Corporation - Hawkins, Delafield & Wood LLP Appraisal and Market Study Consultant Pre-qualified Panel of the: ▸ New York State Housing Finance Agency - Capital Appraisal Services, Inc. -

STARRETT-LEHIGH BUILDING, 601-625 West 26Th Street, Borough of Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission October 7, 1986; Designation List 186 LP-1295 STARRETT-LEHIGH BUILDING, 601-625 west 26th Street, Borough of Manhattan. Built 1930-31; Russell G. and Walter M. Cory, architects; Yasuo Matsui, associate architect; Purdy & Henderson, consulting engineers. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 672, Lot 1. On April 13, 1982, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Starrett-Lehigh Building, and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 20). The hearing was continued to June 8, 1982 (Item No. 3). Both hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Four witnesses spoke in favor of designation, and a letter supporting designation was read into the record. Two representatives of the owner spoke at the hearings and took no position regarding the proposed designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Starrett-Lehigh Building, constructed in 1930-31 by architects Russell G. and walter M. Cory with Yasuo Matsui as associate architect and Purdy & Henderson as consulting engineers, is an enormous warehouse building that occupies the entire block bounded by West 26th and 27th Streets and 11th and 12th Avenues. A cooperative venture of the Starrett Investing Corporation and the Lehigh Valley Railroad, and built by Starrett Brothers & Eken, the structure served originally as a freight terminal for the railroad with rental manufacturing and warehouse space above. A structurally complex feat of engineering with an innovative interior arrangement, the Starrett-Lehigh Building is also notable for its exterior design of horizontal ribbon windows alternating with brick and concrete spandrels. -

In Re JDS Uniphase Corporation Securities Litigation 02-CV-01486

1 Joseph J. Tabacco, Jr . (75484) Christopher T. Heffelfinger (118058) 2 Michael W. Stocker (179083) BERMAN DeVALERIO PEASE 3 TABACCO BURT & PUCILLO 425 California Street, Suite 2100 4 San Francisco, CA 94104 Telephone: (415) 433-3200 5 Facsimile: (415) 433-6382 Email: jtabacco@bermanesq .com 6 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] 7 Liaison Counsel for Lead Plaintiff Connecticut 8 Retirement Plans and Trust Fund s 9 Barbara J. Hart Jonathan M. Plasse 10 Louis Gottlieb Lisa Buckser-Schulz 11 David J. Goldsmith Jon Adams 12 LABATON SUCHAROW & RUDOFF LLP 100 Park Avenue 13 New York, NY 10017-5563 Telephone: (212) 907-0700 14 Facsimile: (212) 818-0477 Email: [email protected] 1 5 Email: [email protected] Email : [email protected] 16 Email: lbuckser@labalon .com Email : dgoldsmith@labaton .com 17 Email: [email protected] 18 Lead Counsel for Lead Plaintiff Connecticut Retirement Plans and Trust Funds 19 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COUR T 20 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNI A 2 1 22 IN RE JDS UNIPHASE CORPORATION Master File No . C 02-1486 CW SECURITIES LITIGATION 23 Class Action This Document Relates to: All Actions 24 CERTIFICATE OF SERVIC E 25 26 27 28 [C-02-1486 CW] CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE 1 CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE 2 I, Antoinette Kratenstein, declare that I am over the age of 18 years and not a party to thi s action. My business address is 100 Park Avenue, New York, New York 10017. On November 4 4, 2005, I served the following documents : 1 . LEAD PLAINTIFF'S REPLY TO MOTION FOR CLASS CERTIFICATIO N 6 I AND FOR APPOINTMENT OF CLASS REPRESENTATIVE AND CLASS COUNSEL ; 7 MEMORANDUM OF POINTS AND AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT THEREOF ; and 8 2. -

Emergency Response Incidents

Emergency Response Incidents Incident Type Location Borough Utility-Water Main 136-17 72 Avenue Queens Structural-Sidewalk Collapse 927 Broadway Manhattan Utility-Other Manhattan Administration-Other Seagirt Blvd & Beach 9 Street Queens Law Enforcement-Other Brooklyn Utility-Water Main 2-17 54 Avenue Queens Fire-2nd Alarm 238 East 24 Street Manhattan Utility-Water Main 7th Avenue & West 27 Street Manhattan Fire-10-76 (Commercial High Rise Fire) 130 East 57 Street Manhattan Structural-Crane Brooklyn Fire-2nd Alarm 24 Charles Street Manhattan Fire-3rd Alarm 581 3 ave new york Structural-Collapse 55 Thompson St Manhattan Utility-Other Hylan Blvd & Arbutus Avenue Staten Island Fire-2nd Alarm 53-09 Beach Channel Drive Far Rockaway Fire-1st Alarm 151 West 100 Street Manhattan Fire-2nd Alarm 1747 West 6 Street Brooklyn Structural-Crane Brooklyn Structural-Crane 225 Park Avenue South Manhattan Utility-Gas Low Pressure Noble Avenue & Watson Avenue Bronx Page 1 of 478 09/30/2021 Emergency Response Incidents Creation Date Closed Date Latitude Longitude 01/16/2017 01:13:38 PM 40.71400364095638 -73.82998933154158 10/29/2016 12:13:31 PM 40.71442154062271 -74.00607638041981 11/22/2016 08:53:17 AM 11/14/2016 03:53:54 PM 40.71400364095638 -73.82998933154158 10/29/2016 05:35:28 PM 12/02/2016 04:40:13 PM 40.71400364095638 -73.82998933154158 11/25/2016 04:06:09 AM 40.71442154062271 -74.00607638041981 12/03/2016 04:17:30 AM 40.71442154062271 -74.00607638041981 11/26/2016 05:45:43 AM 11/18/2016 01:12:51 PM 12/14/2016 10:26:17 PM 40.71442154062271 -74.00607638041981 -

Skyscrapers and District Heating, an Inter-Related History 1876-1933

Skyscrapers and District Heating, an inter-related History 1876-1933. Introduction: The aim of this article is to examine the relationship between a new urban and architectural form, the skyscraper, and an equally new urban infrastructure, district heating, both of witch were born in the north-east United States during the late nineteenth century and then developed in tandem through the 1920s and 1930s. These developments will then be compared with those in Europe, where the context was comparatively conservative as regards such innovations, which virtually never occurred together there. I will argue that, the finest example in Europe of skyscrapers and district heating planned together, at Villeurbanne near Lyons, is shown to be the direct consequence of American influence. Whilst central heating had appeared in the United Kingdom in the late eighteenth and the early nineteenth centuries, district heating, which developed the same concept at an urban scale, was realized in Lockport (on the Erie Canal, in New York State) in the 1880s. In United States were born the two important scientists in the fields of heating and energy, Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) and Benjamin Thompson Rumford (1753-1814). Standard radiators and boilers - heating surfaces which could be connected to central or district heating - were also first patented in the United States in the late 1850s.1 A district heating system produces energy in a boiler plant - steam or high-pressure hot water - with pumps delivering the heated fluid to distant buildings, sometimes a few kilometers away. Heat is therefore used just as in other urban networks, such as those for gas and electricity. -

Atomic Energy Commission

FEDERAL REGISTER VOLUME 30 • NUMBER 106 Thursday, June 3, 1965 • Washington, D.C. Pages 7307-7364 Agencies in this issue— Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service Atomic Energy Commission Civil Service Commission Coast Guard Consumer and Marketing Service Federal Aviation Agency Federal Communications Commission Federal Home Loan Bank Board Federal Maritime Commission Federal Power Commission Fish and Wildlife Service Immigration and Naturalization Service Interstate Commerce Commission Land Management Bureau Securities and Exchange Commission Small Business Administration Detailed list of Contents appears inside. Announcing a New Statutory Citations Guide How to Find U.S. Statutes and U.S. Code Citations This pamphlet contains typical legal refer them to make the search. Additional ence situations which require further citing. finding aids, some especially useful in Official published volumes in which the citing current material, also have been citations may be found are shown along included. Examples are furnished at per side each reference— with suggestions as tinent points and a list of reference titles, to the logical sequence to follow in using with descriptions, is carried at the end. Price: 10 cents Compiled by Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration [Published by the Committee on the judiciary, House of Representatives] Order from Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 20402 Published daily, Tuesday through Saturday (no publication on Sundays, Mondays, or FEHERALMREGISTER on the day after an official Federal holiday), by the Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration (mail address National Area Code 202 \ , 193« ¿jp Phone 963-3261 Archives Building, Washington, D.C. -

Standardization Activities in the United States

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Frederick H. Mueller, Secretary NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS A. V. Astin, Director STANDARDIZATION ACTIVITIES IN THE UNITED STATES A DESCRIPTIVE DIRECTORY Sherman F. Booth Miscellaneous Publication 230 Issued August 1, 1960 (Supersedes Miscellaneous Publication M169) For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D.C. - Price $1.75 I FOREWORD This volume provides a descriptive inventory of the work of about 350 American organizations involved in standardization activities. It is significant that standards and good measurement practices are disseminated in this country through the work of these many organiza- tions. This Nation's achievement in technology—particularly in mass production and automation—is due in no small measure to such activities. The National Bureau of Standards is proud of its cooperative association with these organizations. This cooperative roll stems from one of the Bureau's important functions as set forth by the Congress: " Cooperation with other Government agencies and with pri- vate organizations in the establishment of standard practices, incor- porated in codes and specifications". Through such cooperation the Bureau's effort to develop new and better physical standards serves these organizations in their important task of developing effective industrial standards of practice. The present volume grew out of the Bureau's interest in further- ing these cooperative activities. It describes the organization and functions of the societies and Government agencies that are closely identified with standards activities. It should be of value to man- ufacturers, engineers, purchasing agents, and writers of standards and specifications. A. V. Astin, Director. -

FUNDRAISING CALM “Greater Giving Has Proven to Be Both a Time and Money Saver for Us

BuyersGuide_2016_June July 06 Exempt 11/18/15 4:02 PM Page 1 TM THE NONPROFITTIMES TM Buyers’ Guide THE AUTHORITATIVE DIRECTORY OF SUPPLIERS TO NONPROFIT ORGANIZATIONS 2016 BuyersGuide_2016_June July 06 Exempt 11/18/15 4:02 PM Page 2 BuyersGuide_2016_June July 06 Exempt 11/18/15 4:02 PM Page 3 2016 BUYERS’ GUIDE THE NONPROFITTIMES ACCOUNTING SERVICES Quatrro FPO Solutions .......................................................................(866) 622-7011 6400 Shafer Court, Rosemont, IL 60018 Accounting Management Solutions, Inc. .......................................(212) 984-0711 Talley Management Group, Inc. .......................................................(856) 423-7222 1501 Broadway, 12th Floor, New York, NY 10036 19 Mantua Road, Mt. Royal, NJ 08061 Blum Shapiro .......................................................................................(860) 570-6400 Tullis Consulting & Financial Services, LLC .................................(908) 617-0167 29 South Main Street, P.O. Box 272000, West Hartford, CT 06127 PO Box 2197, Elizabeth, NJ 07207 CBIZ/MHM ...........................................................................................(617) 761-0584 Wegner CPAs .......................................................................................(888) 204-7665 500 Boylston Street, Boston, MA 02116 230 Park Ave., 10th Floor, New York, NY 10146 Cohn Reznick .......................................................................................(212) 297-0400 1212 Avenue of the America, New York City, NY 10036 ADVERTISING -

2005 NYC Vol Expo.Pdf

6ÕÌiiÀà ,}ÊÕ«ÊÃiiÛiðÊ*ÌV }Ê°Ê/>}Ê>VÌ° Ê `ÃÊ>««>Õ`ÃÊÌ iÊVÌiÌÊ>`ÊëÀÌ vÊÛÕÌiiÀÃÊÜ Ê>iÊ>Ê`vviÀiVi° 7iÊ«ÀÕ`ÞÊÃÕ««ÀÌ / iÊ iÜÊ9ÀÊ ÌÞʸ- >ÀiÊ9ÕÀÊi>À̸ 6ÕÌiiÀÊ Ý«° Ê `ðÊ" Ê/° ÜÜÜ°V `°V February 2005 On behalf of the Manhattan Chamber of Commerce Community Benefit Fund and Grand Central Terminal, Welcome! We are delighted that you have joined us for the first NYC Volunteer Expo to be held in the Big Apple! Our Manhattan Chamber of Commerce Community Benefit Fund is dedicated to supporting non-profit organizations throughout Manhattan and we are very happy to bring 60 organizations to this event to promote their services to you! Our intention is to bring visibility to the many non-profit organizations exhibiting here in Vanderbilt Hall and to help them find new volunteers to support their very worthy missions. These organizations are the unsung heroes in our city, providing services that help to improve the quality of life of all New Yorkers. This event would not have taken place without our able-bodied Steering Committee; Phyllis White-Thorne of Con Edison, Patricia Cole of JP Morgan Chase and Nina Liebman whose initial inquiry to us about volunteer opportunities planted the seed which grew into Share Your Heart, NYC…Volunteer! And many thanks to the Corporate Volunteers of New York, especially to Liza Fabian Illonardo, Rebecca Sherman and Margot Cochran whose hard work and efforts with the exhibiting organizations brought them to this event. We would also like to recognize Paul Kastner of Jones Lang LaSalle representing Grand Central Terminal, who immediately stepped up to the plate to take the lead as Presenting Sponsor of the expo. -

792-0300 [email protected]

LIST OF APPROVED CONTRACTORS October 2016 Construction Manager S. T. Rud Construction Corp. Tom Duffe 1 Bryant Park (212) 257-6550 New York, NY 10036 [email protected] John Gallin & Son, Inc. Andrew Cortese 102 Madison Avenue – 9th Floor (212) 252-8900 New York, NY 10016 [email protected] StructureTone Inc. David Leitner 770 Broadway – 9th Floor (212) 481-6100 New York, NY 10003 [email protected] Hunter Roberts Interiors Michael Beirne 55 Water Street – 51st Floor (212) 792-0300 New York, NY 10041 [email protected] Petretti & Associates Lawrence Petretti 149 Madison Ave, 3rd Floor (212) 259-0433 New York, NY 10016 [email protected] J. T. Magen & Co. Maurice Regan 44 West 28th Street – 11th Floor (212) 790-4200 New York, NY 10001 [email protected] Cross Management Corporation John Fleming 10 East 40th Street – Suite 1200 (212) 922-1110 New York, NY 10016 [email protected] Icon Interiors Inc. Jonathan Bennis 307 7th Ave. – Suite 203 (212) 675-9180 New York, NY 10001 [email protected] Turner Interiors [Turner Construction Company] Bert Rahm 375 Hudson Street – 6th Floor (212) 229-6043 New York, NY 10014 [email protected] James E. Fitzgerald, Inc. John Fitzgerald 252 West 38th Street, 10th Floor (212) 930-3030 New York, NY 10018 [email protected] Clune Construction Company Tommy Dwyer The Chrysler Center (646) 569-3220 405 Lexington Avenue – 27th Floor [email protected] New York, NY 10174 Electrical Contractors Schlesinger Electrical Contractors, Inc. Alan Burczyk 664 Bergen St. (718) 636-3944 Brooklyn, NY 11238 [email protected] Star Delta Electric LLC Randy D’Amico 17 Battery Pl #203 (212) 943-5527 New York, NY 10004 [email protected] Fred Geller Electrical, Inc. -

I N D U S T R I a L S U B L I

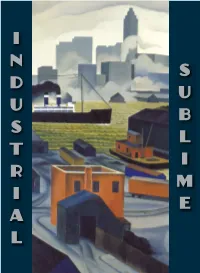

Art/New York/History Billowing smoke, booming industry, noble bridges, and an epic waterfront are the landscape of a transforming New I York from 1900 to 1940. The convulsive changes in the N metropolis and its rivers are embraced in modern paintings from Robert Henri to Georgia O’Keeffe. D I U S N T S R I D A U L U B s S u L b l T i I m R e M The book is the companion catalogue to the exhibition Industrial Sublime: Modernism and the Transformation of New York’s Rivers, 1900 to 1940. fordham university press hudson river museum I The project is organized by Kirsten M. Jensen and Bartholomew F. Bland. COVER DETAILS E FRONT: George Ault. From Brooklyn Heights, 1925. Collection of the Newark Museum BACK: John Noble. The Building of Tidewater, c.1937, The Noble Maritime Collection; George Parker. East River, N.Y.C., 1939. Collection of the New-York Historical Society; Everett Longley Warner. Peck Slip, N.Y.C., n.d. Collection of the New-York Historical Society; Ernest A Lawson. Hoboken Waterfront, c. 1930. Collection of the Norton Museum of Art A COPUBLICATION OF L Empire State Editions An imprint of Fordham University Press New York www.hrm.org www.fordhampress.com INDUSTRIAL SUBLIME INDUSTRIAL SUBLIME Modernism and the Transformation of New York’s Rivers, 1900-1940 Empire State Editions An imprint of Fordham University Press New York Hudson River Museum www.hrm.org www.fordhampress.com I know it’s unusual for an artist to want to work way up near the roof of a big hotel, in the heart of a roaring city, but I think that’s just what the artist of today needs for stimulus..