Where Is the Deliberative Turn Going? a Survey Study of the Impacts of Public Consultation and Deliberation in China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Risk Factors for Carbapenem-Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa, Zhejiang Province, China

Article DOI: https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2510.181699 Risk Factors for Carbapenem-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Zhejiang Province, China Appendix Appendix Table. Surveillance for carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in hospitals, Zhejiang Province, China, 2015– 2017* Years Hospitals by city Level† Strain identification method‡ excluded§ Hangzhou First 17 People's Liberation Army Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou Red Cross Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou First People’s Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Hangzhou Children's Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou Hospital of Chinese Traditional Hospital 3A Phoenix 100, VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou Cancer Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Xixi Hospital of Hangzhou 3A VITEK 2 Compact Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University 3A MALDI-TOF MS The Children's Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine 3A MALDI-TOF MS Women's Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University 3A VITEK 2 Compact The First Affiliated Hospital of Medical School of Zhejiang University 3A MALDI-TOF MS The Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of 3A MALDI-TOF MS Medicine Hangzhou Second People’s Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Zhejiang People's Armed Police Corps Hospital, Hangzhou 3A Phoenix 100 Xinhua Hospital of Zhejiang Province 3A VITEK 2 Compact Zhejiang Provincial People's Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Zhejiang Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine 3A MALDI-TOF MS Tongde Hospital of Zhejiang Province 3A VITEK 2 Compact Zhejiang Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Zhejiang Cancer -

Barcode:3844251-01 A-570-112 INV - Investigation

Barcode:3844251-01 A-570-112 INV - Investigation - PRODUCERS AND EXPORTERS FROM THE PRC Producer/Exporter Name Mailing Address A-Jax International Co., Ltd. 43th Fei Yue Road, Zhongshan City, Guandong Province, China Anhui Amigo Imp.&Exp. Co., Ltd. Private Economic Zone, Chaohu, 238000, Anhui, China Anhui Sunshine Stationery Co., Ltd. 17th Floor, Anhui International Business Center, 162, Jinzhai Road, Hefei, Anhui, China Anping Ying Hang Yuan Metal Wire Mesh Co., Ltd. No. 268 of Xutuan Industry District of Anping County, Hebei Province, 053600, China APEX MFG. CO., LTD. 68, Kuang-Chen Road, Tali District, Taichung City, 41278, Taiwan Beijing Kang Jie Kong 9-2 Nanfaxin Sector, Shunping Rd, Shunyi District, Beijing, 101316, China Changzhou Kya Fasteners Co., Ltd. Room 606, 3rd Building, Rongsheng Manhattan Piaza, Hengshan Road, Xinbei District, Changzhou City, Jiangsu, China Changzhou Kya Trading Co., Ltd. Room 606, 3rd Building, Rongsheng Manhattan Piaza, Hengshan Road, Xinbei District, Changzhou City, Jiangsu, China China Staple #8 Shu Hai Dao, New District, Economic Development Zone, Jinghai, Tianjin Chongqing Lishun Fujie Trading Co., Ltd. 2-63, G Zone, Perpetual Motor Market, No. 96, Torch Avenue, Erlang Technology New City, Jiulongpo District, Chongqing, China Chongqing Liyufujie Trading Co., Ltd. No. 2-63, Electrical Market, Torch Road, Jiulongpo District, Chongqing 400000, China Dongyang Nail Manufacturer Co.,Ltd. Floor-2, Jiaotong Building, Ruian, Wenzhou, Zhejiang, China Fastco (Shanghai) Trading Co., Ltd. Tong Da Chuang Ye, Tian -

Factory Address Country

Factory Address Country Durable Plastic Ltd. Mulgaon, Kaligonj, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh Lhotse (BD) Ltd. Plot No. 60&61, Sector -3, Karnaphuli Export Processing Zone, North Potenga, Chittagong Bangladesh Bengal Plastics Ltd. Yearpur, Zirabo Bazar, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh ASF Sporting Goods Co., Ltd. Km 38.5, National Road No. 3, Thlork Village, Chonrok Commune, Korng Pisey District, Konrrg Pisey, Kampong Speu Cambodia Ningbo Zhongyuan Alljoy Fishing Tackle Co., Ltd. No. 416 Binhai Road, Hangzhou Bay New Zone, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Ningbo Energy Power Tools Co., Ltd. No. 50 Dongbei Road, Dongqiao Industrial Zone, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Junhe Pumps Holding Co., Ltd. Wanzhong Villiage, Jishigang Town, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Skybest Electric Appliance (Suzhou) Co., Ltd. No. 18 Hua Hong Street, Suzhou Industrial Park, Suzhou, Jiangsu China Zhejiang Safun Industrial Co., Ltd. No. 7 Mingyuannan Road, Economic Development Zone, Yongkang, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Dingxin Arts&Crafts Co., Ltd. No. 21 Linxian Road, Baishuiyang Town, Linhai, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Natural Outdoor Goods Inc. Xiacao Village, Pingqiao Town, Tiantai County, Taizhou, Zhejiang China Guangdong Xinbao Electrical Appliances Holdings Co., Ltd. South Zhenghe Road, Leliu Town, Shunde District, Foshan, Guangdong China Yangzhou Juli Sports Articles Co., Ltd. Fudong Village, Xiaoji Town, Jiangdu District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu China Eyarn Lighting Ltd. Yaying Gang, Shixi Village, Shishan Town, Nanhai District, Foshan, Guangdong China Lipan Gift & Lighting Co., Ltd. No. 2 Guliao Road 3, Science Industrial Zone, Tangxia Town, Dongguan, Guangdong China Zhan Jiang Kang Nian Rubber Product Co., Ltd. No. 85 Middle Shen Chuan Road, Zhanjiang, Guangdong China Ansen Electronics Co. Ning Tau Administrative District, Qiao Tau Zhen, Dongguan, Guangdong China Changshu Tongrun Auto Accessory Co., Ltd. -

Inquiry Into the Wenzhou Model of Industrial Development In

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Insitutional Repository at the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies From Inferior to Superior Products: An Inquiry into the Wenzhou Model of Industrial Development in China1 Tetsushi Sonobe, Foundation for Advanced Studies on International Development, Tokyo 162-8677, Japan Dinghuan Hu Institute of Agricultural Economics, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing 100081, China Keijiro Otsuka Foundation for Advanced Studies on International Development, Tokyo 162-8677, Japan (May 2004) Running head: Wenzhou Model of Industrial Development 1 From Inferior to Superior Products: An Inquiry into the Wenzhou Model of Industrial Development in China Abstract Although the vitality of small private enterprises as the prime mover of the substantial economic growth in Wenzhou is widely recognized, empirical research investigating the development process of such private enterprises is useful. Based on a survey of enterprises producing low-voltage electric appliances, we find that the entry of a large number of new enterprises producing poor-quality products was followed by the upgrading of product quality and the introduction of new marketing strategies. Hence, we attempt to identify statistically the mechanisms underlying this evolutionary process of industrial development. JEL classification numbers: O12, P23 2 1. Introduction China’s substantial economic growth in the 1980s is attributable mainly to township- and village enterprises (TVEs) according to Chen et al. (1992), Jefferson et al. (1996), and Otsuka et al. (1998). However, the private sector emerged as the new engine of Chinese economic growth in the 1990s. The heartland of this private sector growth is Zhejiang Province, particularly in Wenzhou City as Zhang (1989), Nolan (1990), Dong (1990), Wang (1996), Li (1997), Zhang (1999) and Sonobe et al. -

China – Zheijang Province – Cixi City – Catholic Church – Underground

Country Advice China China – CHN37465 – Zheijang Province – Cixi City – Catholic Church – Underground Catholics – Bishop of Ningbo 24 September 2010 1. Please provide information on the registered and unregistered Catholic Church in Cixi City, Zheijang and whether any Bishops have been recognised by both the Pope and the government in this area. The Guide to the Catholic Church in China (2008)1 provides the following information on the Catholic community in Cixi City: Cixi (60km north-west of Ningbo); 27 centres, 10,000 Catholics Xinpu Shuixiang St John Church Tel: 86-5476357 4326 Xushan Jianchangshan Cat. Church Tel: 86-547-6389 0642 The Guide does not specify whether this information relates to the registered or the unregistered Catholic Church in Cixi City. The information may relate to both the registered and the unregistered Church, as the communities do overlap in some parts of China. The Catholic Church in Zhejiang Province is divided administratively into four dioceses: Hangzhou, Ningbo, Wenzhou, and Taizhou. The Cixi City Catholic community is part of the Ningbo Diocese. The current Bishop of Ningbo is Hu Xiande.2 No information was found on whether Bishop Hu Xiande has been recognised by either the Pope or the government. Dual recognition has occurred previously in this area of China. The previous Bishop of Ningbo, Michael He Jinmin, who died in May 2004, was recognised by both the Pope and the government.3 1 Charbonnier, Fr. J. 2008, Guide to the Catholic Church in China, China Catholic Communication, Singapore, pp. 508-510 – Attachment 1. 2 Charbonnier, Fr. J. 2008, Guide to the Catholic Church in China, China Catholic Communication, Singapore, pp. -

Wenzhou Lingyu Import and Export Co.,Ltd G122

1 List of Exhibitor-Alphabetical Name of Exhibitor Country Stand No. H Haining Youdiweiya Trading Co.,Ltd China G130 Hangzhou Belf Technology Co.,Ltd China G102 Hangzhou Great Fate Import & Export Co.,Ltd China G104 Hangzhou Huashan Electric Co.,Ltd. China G108 Hangzhou Lighting Import Export Ltd China G101 Hangzhou Tiger Electron & Electric Co.,Ltd China G103 Hangzhou Yongdian Illumination Co., Ltd. China G106 Hangzhou Yuzhong Gaohong Lighting Electrical Equipment Co.,Ltd. China G109 Hangzhou ZGSM Technology Co.,Ltd China G107 Huzhou Jiwei Electronics Technology Co., Ltd China G126 J Jiaxing Bingsheng Energy & Technology Co. Ltd China G129 Jiaxing Ledux Lighting Co.,Ltd China G131 L Lanting Photoelectric Co., Ltd. China G124 N Ningbo Bull International Trading Co.,Ltd. China G114 Ningbo Cosmos Lighting Co.,Ltd China G117 Ningbo Eurolite Co., Ltd. China G116 Ningbo Freelux Lighting Appliance Co.,Ltd China G118 NingBo Hengjian Photoelectron Technology Co.,Ltd China G113 Ningbo Horari Lighting Co.,Ltd China G151 Ningbo Shenghe Lighting Co.,Ltd China G112 Ningbo Shining Opto Electronics Corp., Ltd China G149 Ningbo Zehai Lighting Co.,Ltd China G115 Ningbo Zhongce Electronics Co.,Ltd China G150 Q Quzhou Utop Electronic Technology Co.,Ltd China G138 S Shaoxing Belo Electrical Products Co.,Ltd China G135 Shaoxing Ledme Electronics Co.,Ltd China G134 Shaoxing Meka Electric Imp&Exp Co.,Ltd China G136 Shaoxing Shangyu Jinghua Background Lighting Co., Ltd. China G132 Shaoxing Shangyu YoYo Lighting Electric Appliance Co.,Ltd China G133 Shaoxing Sunshine Electronic Co., Ltd China G147 2 List of Exhibitor-Alphabetical Name of Exhibitor Country Stand No. W Wenzhou DGT Lighting Co.,Ltd China G120 Wenzhou Lingyu Import And Export Co.,Ltd China G122 Wenzhou Ni'S Neon Light Co.,Ltd China G146 Y Yueqing Huihua Electronic Co.,Ltd China G125 Yuyao Yuhe Electrical Appliance Co.,Ltd China G119 Yuyao Yusheng Lighting Co., Ltd China G145 Z Zhaoliang (Hangzhou) Technology Co., Ltd China G105 Zhejiang Antong ELEC&TECH. -

An Analysis of China's Industrial Cluster(Zhejiang Province Pattern)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Archive - Università di Pisa An analysis of China's industrial cluster(Zhejiang province pattern): historical development, questions and prospective in pursuit of sustainable competitive advantage-the case of Datang and Sassuolo 1. Introduction Today's economy is dominated by inter-firms networks, which have become powerful instruments for building competitive capacity in the global market place. Industry clusters are recognized as an important role in both regional and national economy. As M. E. Porter pointed out, economic map of the world is filled with regions known as clusters today. [1] Under the current climate of rapid industrial development in China, the outstanding contribution from industrial districts or clusters has been widely accepted and acknowledged by researchers and government. The intention of this paper is to analyze this phenomenon from the development, characteristics, drivers and problems of industrial clusters in the province of Zhejing, China by comparing two clusters: Datang hosiery cluster and Sassuolo ceramic tiles cluster--which is a prototype of successful industrial cluster from developed country. This comparative method helps understand that in many ways, the Zhejiang districts appear to have many similarities with the development observed in the 3rd Italy; however, we can distinguish the features and dissimilarities between these two types of clusters – the very structure factors that render the clusters highly specific. Finally, this paper will also point out some server problems of Chinese industrial cluster, which all will be helpful for us to know the situation of China SME industrial clusters. -

Attachment I

Foreign Producers of Steel Threaded Rod: The People's Republic of China Barcode:3795402-02 A-570-104 INV - Investigation - Shipper Shipper Full Address Shipper Email Shipper Phone Number Shippper Fax Number Shipper Website Aaa Line International Room 502-A01 East Area Bldg., 129 Jiatai Road, Shanghai, Shanghai, China 200000 Not Available +86 21 5054 1289 Not Available Not Available Ace Fastech Co., Ltd. No. 583-28, Chang'An North Road, Wuyan Town, Haiyan, Zhejiang, China, 314300 Not Available Not Available Not Available Not Available Aerospace Precision Corp. (Shanghai) Room 3E, 1903 Pudong Ave., Pudong, Shanghai, China 200120 Not Available +86 187 2262 6510 +86 187 5823 7600 Not Available Aihua Holding Group Co., Ltd. 12F, New Taizhou Building, Jiaojiang, Zhejiang, China, 318000 Not Available +86 576 8868 5829 +86 576 8868 5815 Not Available All Tech Hardware Ltd. Suite 2406, Dragon Pearl Complex, No. 2123 Pudong Ave. Shanghai, China 200135 Not Available Not Available Not Available Not Available All World Shipping Corp. Room 503, Building B, Guangpi Cultural Plaza, No. 2899A Xietu Road, Shanghai, China 20030 [email protected] +86 21 6487 9050 +86 21 6487 9071 allworldshipping.com Alloy Steel Products Inc. No. 188 Siping Road No.89, Hongkou, Shanghai, China 200086 Not Available +86 21 6409 2892 Not Available Not Available America And Asia Products Inc. Rm. 508, No. 188 Siping Road, Hongkou, Shanghai, China 200086 Not Available +86 21 6142 8806 Not Available Not Available Ams No Chinfast Co., Ltd. 68 Qin Shan Road, Haiyan, Jiaxing, Zhejiang, China 314000 Not Available +86 573 8211 9789 Not Available Not Available Ams No Jiaxing Xinyue Standard Parts Co., Ltd. -

SUPPLIER LIST AUGUST 2019 Cotton on Group - Supplier List 2

SUPPLIER LIST AUGUST 2019 Cotton On Group - Supplier List _2 COUNTRY FACTORY NAME SUPPLIER ADDRESS STAGE TOTAL % OF % OF % OF TEMP WORKERS FEMALE MIGRANT WORKER WORKERS WORKER CHINA NINGBO FORTUNE INTERNATIONAL TRADE CO LTD RM 805-8078 728 LANE SONGJIANG EAST ROAD SUP YINZHOU NINGBO, ZHEJIANG CHINA NINGBO QIANZHEN CLOTHES CO LTD OUCHI VILLAGE CMT 104 64% 75% 6% GULIN TOWN, HAISHU DISTRICT NINGBO, ZHEJIANG CHINA XIANGSHAN YUFA KNITTING LTD NO.35 ZHENYIN RD, JUEXI STREET CMT 57 60% 88% 12% XIANGSHAN COUNTY NINGBO CITY, ZHEJIANG CHINA SUNROSE INTERNATIONAL CO LTD ROOM 22/2 227 JINMEI BUILDING NO 58 LANE 136 SUP SHUNDE ROAD, HAISHU DISTRICT NINGBO, ZHEJIANG CHINA NINGBO HAISHU WANQIANYAO TEXTILE CO LTD NO 197 SAN SAN ROAD CMT 26 62% 85% 0% WANGCHAN INDUSTRIAL ZONE NINGBO, ZHEJIANG CHINA ZHUJI JUNHANG SOCKS FACTORY DAMO VILLAGE LUXI NEW VILLAGE CMT 73 38% 66% 0% ZHUJI CITY ZHEJIANG CHINA SKYLEAD INDUSTRY CO LIMITED LAIMEI INDUSTRIAL PARK SUP CHENGHAI DISTRICT, SHANTOU CITY GUANGDONG CHINA CHUANGXIANG TOYS LIMITED LAIMEI INDUSTRIAL PARK CMT 49 33% 90% 0% CHENGHAI DISTRICT SHANTOU, GUANGDONG CHINA NINGBO ODESUN STATIONERY & GIFT CO LTD TONGJIA VILLAGE, PANHUO INDUSTRIAL ZONE SUP YINZHOU DISTRICT NINGBO CITY, ZHEJIANG CHINA NINGBO ODESUN STATIONERY & GIFT CO LTD TONGJIA VILLAGE, PANHUO INDUSTRIAL ZONE CMT YINZHOU DISTRICT NINGBO CITY, ZHEJIANG CHINA NINGBO WORTH INTERNATIONAL TRADE CO LTD RM. 1902 BUILDING B, CROWN WORLD TRADE PLAZA SUP NO. 1 LANE 28 BAIZHANG EAST ROAD NINGBO ZHEJIANG CHINA NINGHAI YUEMING METAL PRODUCT CO LTD NO. 5 HONGTA ROAD -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 231/Tuesday, December 1, 2020

77240 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 231 / Tuesday, December 1, 2020 / Notices Trade Commission, 500 E Street SW, (Tianjin) International Trade Co., Ltd. of Practice and Procedure, 19 CFR part Washington, DC 20436, telephone (202) Tianjin, China; Shenzhen Yaxin General 210. 205–2392. Copies of non-confidential Machinery Co., Ltd. of Shenzhen, China; By order of the Commission. documents filed in connection with this Dunhuang Group a.k.a. DHgate of Issued: November 24, 2020. investigation may be viewed on the Beijing, China; Eddie Bauer, LLC of William Bishop, Bellevue, Washington; PSEB Holdings, Commission’s electronic docket (EDIS) Supervisory Hearings and Information at https://edis.usitc.gov. For help LLC of Wilmington, Delaware; and Officer. accessing EDIS, please email HydroFlaskPup of Phoenix, Arizona. Id. [FR Doc. 2020–26409 Filed 11–30–20; 8:45 am] [email protected]. General at 55031. The Commission’s Office of BILLING CODE 7020–02–P information concerning the Commission Unfair Import Investigations (‘‘OUII’’) is may also be obtained by accessing its also named as a party in this internet server at https://www.usitc.gov. investigation. Id. Hearing-impaired persons are advised On October 16, 2020, Complainants DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE that information on this matter can be moved to amend the complaint and notice of investigation to: ‘‘(1) assert the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms obtained by contacting the and Explosives Commission’s TDD terminal on (202) ’012 patent against additional infringing 205–1810. products sold by Everich; (2) [OMB Number 1140–0080] incorporate into the complaint the SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: On information and additional paragraphs Agency Information Collection September 3, 2020, the Commission included in Complainants’ Activities; Proposed eCollection instituted this investigation under Supplemental Letter to the Commission eComments Requested; Notification of section 337 of the Tariff Act of 1930, as of August 18, 2020; and (3) correct the Change of Mailing or Premise Address amended, 19 U.S.C. -

The Order of Local Things: Popular Politics and Religion in Modern

The Order of Local Things: Popular Politics and Religion in Modern Wenzhou, 1840-1940 By Shih-Chieh Lo B.A., National Chung Cheng University, 1997 M.A., National Tsing Hua University, 2000 A.M., Brown University, 2005 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History at Brown University PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND May 2010 © Copyright 2010 by Shih-Chieh Lo ii This dissertation by Shih-Chieh Lo is accepted in its present form by the Department of History as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date_____________ ________________________ Mark Swislocki, Advisor Recommendation to the Graduate Council Date_____________ __________________________ Michael Szonyi, Reader Date_____________ __________________________ Mark Swislocki, Reader Date_____________ __________________________ Richard Davis, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date______________ ___________________________ Sheila Bonde, Dean of the Graduate School iii Roger, Shih-Chieh Lo (C. J. Low) Date of Birth : August 15, 1974 Place of Birth : Taichung County, Taiwan Education Brown University- Providence, Rhode Island Ph. D in History (May 2010) Brown University - Providence, Rhode Island A. M., History (May 2005) National Tsing Hua University- Hsinchu, Taiwan Master of Arts (June 2000) National Chung-Cheng University - Chaiyi, Taiwan Bachelor of Arts (June 1997) Publications: “地方神明如何平定叛亂:楊府君與溫州地方政治 (1830-1860).” (How a local deity pacified Rebellion: Yangfu Jun and Wenzhou local politics, 1830-1860) Journal of Wenzhou University. Social Sciences 溫州大學學報 社會科學版, Vol. 23, No.2 (March, 2010): 1-13. “ 略論清同治年間台灣戴潮春案與天地會之關係 Was the Dai Chaochun Incident a Triad Rebellion?” Journal of Chinese Ritual, Theatre and Folklore 民俗曲藝 Vol. 138 (December, 2002): 279-303. “ 試探清代台灣的地方精英與地方社會: 以同治年間的戴潮春案為討論中心 Preliminary Understandings of Local Elites and Local Society in Qing Taiwan: A Case Study of the Dai Chaochun Rebellion”. -

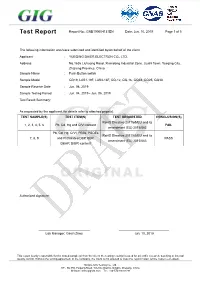

Test Report Report No.: GNB190604131EN Date: Jun

Report No.: GNB190604131EN Date: Jun. 10, 2019 Page 1 of 5 Test Report The following information was/were submitted and identified by/on behalf of the client: Applicant : YUEQING DAIER ELECTRON CO., LTD. Address : No.1636 Liuhuang Road, Xirendang Industrial Zone, Liushi Town, Yueqing City, Zhejiang Province, China Sample Name : Push Button switch Sample Model : GQ19, LAS1-19F, LAS3-16F, GQ-12, GQ-16, GQ22, GQ25, GQ30 Sample Receive Date : Jun. 04, 2019 Sample Testing Period : Jun. 04, 2019 - Jun. 06, 2019 Test Result Summary: As requested by the applicant, for details refer to attached page(s). TEST SAMPLE(S) TEST ITEM(S) TEST REQUESTED CONCLUSION(S) RoHS Directive 2011/65/EU and its 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Pb, Cd, Hg and CrVI content FAIL amendment (EU) 2015/863 Pb, Cd, Hg, CrVI, PBBs, PBDEs RoHS Directive 2011/65/EU and its 7, 8, 9 and Phthalates(DBP, BBP, PASS amendment (EU) 2015/863 DEHP, DIBP) content Authorized signature: Lab Manager: Gavin Zhou Jun. 10, 2019 This report is only responsible for the tested sample(s) from the client, the testing result(s) is used for scientific research, teaching or internal quality control. Without the writing agreement of the company, the client is not allowed to copy the report in part (entire copy is excepted). Ningbo GIG Testing Co., Ltd. 3/F., No.555, Fuqiang Road, Yinzhou District, Ningbo, Zhejiang, China. Website: www.gig-lab.com Tel.: +86-574-89201291 Report No.: GNB190604131EN Date: Jun. 10, 2019 Page 2 of 5 Test Report Test Result(s): Test Sample Description: Material No.