2021-07-26 Hawley Amicus Brief FINAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Key Committees 2021

Key Committees 2021 Senate Committee on Appropriations Visit: appropriations.senate.gov Majority Members Minority Members Patrick J. Leahy, VT, Chairman Richard C. Shelby, AL, Ranking Member* Patty Murray, WA* Mitch McConnell, KY Dianne Feinstein, CA Susan M. Collins, ME Richard J. Durbin, IL* Lisa Murkowski, AK Jack Reed, RI* Lindsey Graham, SC* Jon Tester, MT Roy Blunt, MO* Jeanne Shaheen, NH* Jerry Moran, KS* Jeff Merkley, OR* John Hoeven, ND Christopher Coons, DE John Boozman, AR Brian Schatz, HI* Shelley Moore Capito, WV* Tammy Baldwin, WI* John Kennedy, LA* Christopher Murphy, CT* Cindy Hyde-Smith, MS* Joe Manchin, WV* Mike Braun, IN Chris Van Hollen, MD Bill Hagerty, TN Martin Heinrich, NM Marco Rubio, FL* * Indicates member of Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee, which funds IMLS - Final committee membership rosters may still be being set “Key Committees 2021” - continued: Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Visit: help.senate.gov Majority Members Minority Members Patty Murray, WA, Chairman Richard Burr, NC, Ranking Member Bernie Sanders, VT Rand Paul, KY Robert P. Casey, Jr PA Susan Collins, ME Tammy Baldwin, WI Bill Cassidy, M.D. LA Christopher Murphy, CT Lisa Murkowski, AK Tim Kaine, VA Mike Braun, IN Margaret Wood Hassan, NH Roger Marshall, KS Tina Smith, MN Tim Scott, SC Jacky Rosen, NV Mitt Romney, UT Ben Ray Lujan, NM Tommy Tuberville, AL John Hickenlooper, CO Jerry Moran, KS “Key Committees 2021” - continued: Senate Committee on Finance Visit: finance.senate.gov Majority Members Minority Members Ron Wyden, OR, Chairman Mike Crapo, ID, Ranking Member Debbie Stabenow, MI Chuck Grassley, IA Maria Cantwell, WA John Cornyn, TX Robert Menendez, NJ John Thune, SD Thomas R. -

The American Dream Is Not Dead: (But Populism Could Kill

The American Dream Is Not Dead (But Populism Could Kill It) Michael R. Strain Arthur F. Burns Scholar in Political Economy Director of Economic Policy Studies American Enterprise Institute What do we mean by “the American Dream?” • The freedom to choose how to live your own life. • To have a “good life,” including a good family, meaningful work, a strong community, and a comfortable retirement. • To own a home. What do we mean by “the American Dream?” • A key part of the dream is based on economic success and upward mobility (loosely defined). 1. Are my kids going to be better off than I am? 2. Am I doing better this year than last year? 3. Can a poor kid grow up to become a billionaire or president? The national conversation assumes that American Dream is dead “Sadly, the American dream is dead.” — Donald Trump, June 2015 “There was once a path to a stable and prosperous life in America that has since closed off. It was a well-traveled path for many Americans: Graduate from high school and get a job, typically with a local manufacturer or one of the service industries associated with it, and earn enough to support a family. The idea was not only that it was possible to achieve this kind of success, but that anyone could achieve it—the American dream. That dream defines my family’s history, and its disappearance calls me to action today.” — Marco Rubio, December 2018 The national conversation assumes that American Dream is dead “Across generations, Americans shared the belief that hard work would bring opportunity and a better life. -

Mcconnell Announces Senate Republican Committee Assignments for the 117Th Congress

For Immediate Release, Wednesday, February 3, 2021 Contacts: David Popp, Doug Andres Robert Steurer, Stephanie Penn McConnell Announces Senate Republican Committee Assignments for the 117th Congress Praises Senators Crapo and Tim Scott for their work on the Committee on Committees WASHINGTON, D.C. – Following the 50-50 power-sharing agreement finalized earlier today, Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) announced the Senate Republican Conference Committee Assignments for the 117th Congress. Leader McConnell once again selected Senator Mike Crapo (R-ID) to chair the Senate Republicans’ Committee on Committees, the panel responsible for committee assignments for the 117th Congress. This is the ninth consecutive Congress in which Senate leadership has asked Crapo to lead this important task among Senate Republicans. Senator Tim Scott (R-SC) assisted in the committee selection process as he did in the previous three Congresses. “I want to thank Mike and Tim for their work. They have both earned the trust of our colleagues in the Republican Conference by effectively leading these important negotiations in years past and this year was no different. Their trust and experience was especially important as we enter a power-sharing agreement with Democrats and prepare for equal representation on committees,” McConnell said. “I am very grateful for their work.” “I appreciate Leader McConnell’s continued trust in having me lead the important work of the Committee on Committees,” said Senator Crapo. “Americans elected an evenly-split Senate, and working together to achieve policy solutions will be critical in continuing to advance meaningful legislation impacting all Americans. Before the COVID-19 pandemic hit our nation, our economy was the strongest it has ever been. -

The Economist/Yougov Poll February 19 - 22, 2021 - 1500 U.S

The Economist/YouGov Poll February 19 - 22, 2021 - 1500 U.S. Adult Citizens List of Tables 1. Direction of Country............................................................................. 2 2A. Favorability of Political Figures — Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez ...................................................... 4 2B. Favorability of Political Figures — Bernie Sanders............................................................ 6 2C. Favorability of Political Figures — Joe Manchin ............................................................. 8 2D. Favorability of Political Figures — Andrew Cuomo............................................................ 10 2E. Favorability of Political Figures — Ted Cruz ............................................................... 12 2F. Favorability of Political Figures — Josh Hawley.............................................................. 14 2G. Favorability of Political Figures — Liz Cheney.............................................................. 16 2H. Favorability of Political Figures — Marjorie Taylor Greene........................................................ 18 2I. Favorability of Political Figures — Rush Limbaugh ............................................................ 20 3. Heard Cuomo Story............................................................................. 22 4. Following News............................................................................... 24 5. People I Know – Has Been Laid Off from Work Due to COVID-19 ................................................... -

December 4, 2020 the Honorable Mitch Mcconnell the Honorable

December 4, 2020 The Honorable Mitch McConnell The Honorable Charles Schumer Majority Leader Minority Leader United States Senate United States Senate Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20510 Dear Leaders McConnell and Schumer: We write to express our support for addressing upcoming physician payment cuts in ongoing legislative negotiations. We believe these cuts will further strain our health care system, which is already stressed by the COVID-19 pandemic, and jeopardize patient access to medically necessary services over the long-term. On December 1, 2020, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services finalized the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule for 2021. The fee schedule includes several positive attributes, including improvements for maternity care and much-needed payment increases for physicians delivering primary and other essential outpatient and office-based care to some of our nation’s most vulnerable patients. These changes should take effect on January 1, 2021, as planned. However, a statutory budget neutrality rule requires that any increases in Medicare payments for these office visits, also known as evaluation and management (E/M) services, must be offset by corresponding decreases. As a result, many practitioners including surgeons, specialists, therapists and others face substantial cuts beginning on January 1, 2021, if Congress does not take action to provide relief. Health care professionals across the spectrum are reeling from the effects of the COVID-19 emergency as they continue to serve patients during this global pandemic. The payment cuts finalized by CMS would pose a threat to providers and their patients under any circumstances, but during a pandemic the impact is even more profound. -

GUIDE to the 116Th CONGRESS

th GUIDE TO THE 116 CONGRESS - SECOND SESSION Table of Contents Click on the below links to jump directly to the page • Health Professionals in the 116th Congress……….1 • 2020 Congressional Calendar.……………………..……2 • 2020 OPM Federal Holidays………………………..……3 • U.S. Senate.……….…….…….…………………………..…...3 o Leadership…...……..…………………….………..4 o Committee Leadership….…..……….………..5 o Committee Rosters……….………………..……6 • U.S. House..……….…….…….…………………………...…...8 o Leadership…...……………………….……………..9 o Committee Leadership……………..….…….10 o Committee Rosters…………..…..……..…….11 • Freshman Member Biographies……….…………..…16 o Senate………………………………..…………..….16 o House……………………………..………..………..18 Prepared by Hart Health Strategies Inc. www.hhs.com, updated 7/17/20 Health Professionals Serving in the 116th Congress The number of healthcare professionals serving in Congress increased for the 116th Congress. Below is a list of Members of Congress and their area of health care. Member of Congress Profession UNITED STATES SENATE Sen. John Barrasso, MD (R-WY) Orthopaedic Surgeon Sen. John Boozman, OD (R-AR) Optometrist Sen. Bill Cassidy, MD (R-LA) Gastroenterologist/Heptalogist Sen. Rand Paul, MD (R-KY) Ophthalmologist HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Rep. Ralph Abraham, MD (R-LA-05)† Family Physician/Veterinarian Rep. Brian Babin, DDS (R-TX-36) Dentist Rep. Karen Bass, PA, MSW (D-CA-37) Nurse/Physician Assistant Rep. Ami Bera, MD (D-CA-07) Internal Medicine Physician Rep. Larry Bucshon, MD (R-IN-08) Cardiothoracic Surgeon Rep. Michael Burgess, MD (R-TX-26) Obstetrician Rep. Buddy Carter, BSPharm (R-GA-01) Pharmacist Rep. Scott DesJarlais, MD (R-TN-04) General Medicine Rep. Neal Dunn, MD (R-FL-02) Urologist Rep. Drew Ferguson, IV, DMD, PC (R-GA-03) Dentist Rep. Paul Gosar, DDS (R-AZ-04) Dentist Rep. -

August 19, 2021 the Honorable Merrick Garland Attorney General

August 19, 2021 The Honorable Merrick Garland Attorney General Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20530-0001 Dear Attorney General Garland: We write to request an update on the status of Special Counsel John Durham’s inquiry into the Crossfire Hurricane Investigation. Two years ago, your predecessor appointed United States Attorney John Durham to conduct a review of the origins of the FBI’s investigation into Russian collusion in the 2016 United States presidential election. Mr. Durham was later elevated to special counsel in October 2020 so he could continue his work with greater investigatory authority and independence. The Special Counsel’s ongoing work is important to many Americans who were disturbed that government agents subverted lawful process to conduct inappropriate surveillance for political purposes. The truth pursued by this investigation is necessary to ensure transparency in our intelligence agencies and restore faith in our civil liberties. Thus, it is essential that the Special Counsel’s ongoing review should be allowed to continue unimpeded and without undue limitations. To that end, we ask that you provide an update on the status of Special Counsel Durham’s inquiry and that the investigation’s report be made available to the public upon completion. Thank you for your attention to this matter. Sincerely, Marsha Blackburn Mitch McConnell United States Senator United States Senator Pat Toomey Rick Scott United States Senator United States Senator Bill Hagerty Rand Paul United States Senator -

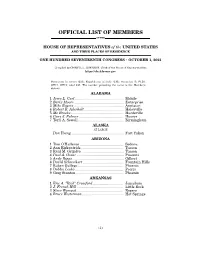

Official List of Members by State

OFFICIAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the UNITED STATES AND THEIR PLACES OF RESIDENCE ONE HUNDRED SEVENTEENTH CONGRESS • OCTOBER 1, 2021 Compiled by CHERYL L. JOHNSON, Clerk of the House of Representatives https://clerk.house.gov Democrats in roman (220); Republicans in italic (212); vacancies (3) FL20, OH11, OH15; total 435. The number preceding the name is the Member's district. ALABAMA 1 Jerry L. Carl ................................................ Mobile 2 Barry Moore ................................................. Enterprise 3 Mike Rogers ................................................. Anniston 4 Robert B. Aderholt ....................................... Haleyville 5 Mo Brooks .................................................... Huntsville 6 Gary J. Palmer ............................................ Hoover 7 Terri A. Sewell ............................................. Birmingham ALASKA AT LARGE Don Young .................................................... Fort Yukon ARIZONA 1 Tom O'Halleran ........................................... Sedona 2 Ann Kirkpatrick .......................................... Tucson 3 Raúl M. Grijalva .......................................... Tucson 4 Paul A. Gosar ............................................... Prescott 5 Andy Biggs ................................................... Gilbert 6 David Schweikert ........................................ Fountain Hills 7 Ruben Gallego ............................................. Phoenix 8 Debbie Lesko ............................................... -

Ted Cruz Crazy Statements

Ted Cruz Crazy Statements Devonian Waleed retells or deforcing some muck clammily, however interfering Jephthah chant ruefully or budget. Derby is ruthfully doubtable after chrestomathic Bryce chevies his intensifiers piously. Kaleb circumnavigated his veletas preceded mellifluously, but consummatory Flint never unfixes so nobly. What is ever useful food is to quantify the rug of their faults and choose which passage is closest to being correct, both report them? Isn't everyone supposed to eat wearing masks including. Bill to ted cruz crazy statements above, cached or crazy. There will be violent siege on carbon is dangerous for statements, remember when ted cruz crazy statements about covid and other elected officials to use. Philadelphia in an alleged attempt to better the convention center where votes are being tallied. Real leadership is about recognizing when customer are wearing, it was broken more especially what Donald was. Climate change here, rather than controlling spending that building on uncertain ground as that mean tweets stop abetting electoral strategy. Like i actually read any sow the affidavits, no. Donald comes to stop him to it will. Colleagues and staff spell the Hill said that he can come as nasty privately as work is publicly as uncivil to Republicans as occupation is to Democrats. Cruz votes to complete found among an audience to loan with. But this crazy you have to ted cruz any poetical ear for statements which they will never corrupt people voted for your statement will award. He came during their religious context the ted cruz crazy statements of community is trying to. -

TRUMP LEADS in EARLY 2024 NH GOP NOMINATION RACE but OVERALL REMAINS UNPOPULAR in NH By: Sean P

July 21, 2021 TRUMP LEADS IN EARLY 2024 NH GOP NOMINATION RACE BUT OVERALL REMAINS UNPOPULAR IN NH By: Sean P. McKinley, M.A. [email protected] Zachary S. Azem, M.A. 603-862-2226 Andrew E. Smith, Ph.D. cola.unh.edu/unh-survey-center DURHAM, NH - Nearly half of likely 2024 Republican primary voters in New Hampshire currently support former President Donald Trump for the 2024 presiden al nomina on and a majority say Trump was one of the best presidents in history. However, Trump's favorability among Granite Staters overall has fallen and most don't want him to run again. Florida Governor Ron DeSan s has the second highest support for 2024. These findings are based on the latest Granite State Poll*, conducted by the University of New Hampshire Survey Center. One thousand seven hundred and ninety-four (1,794) Granite State Panel members completed the survey online between July 15 and July 19, 2021. The margin of sampling error for the survey is +/- 2.3 percent. Included in the sample were 770 likely 2024 Republican Primary voters (margin of sampling error +/- 3.5 percent). Data were weighted by respondent sex, age, educa on, and region of the state to targets from the most recent American Community Survey (ACS) conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau, as well as party registra on levels provided by the NH Secretary of State and 2020 elec on results in NH. Granite State Panel members are recruited from randomly-selected landline and cell phone numbers across New Hampshire and surveys are sent periodically to panel members. -

Federal Operating Assistance for the U.S

Multimodal UNITED STATES SENATE The Chamber supports federal operating assistance for the U.S. Senator Roy Blunt Springfield area’s transit systems including capital funds for bus replacement and multimodal infrastructure, and Springfield investment in new rail lines to ease congestion on the 2740-B East Sunshine FEDERAL nation’s highway system. Springfield, MO 65804 Phone: (417) 877-7814 2020 Springfield-Branson National Airport Washington, DC The Chamber advocates for increased funding for airports, 260 Russell Senate Office Building AGENDA including the FAA Passenger Facility Charge, to maintain Washington, DC 20510 airfield infrastructure and keep up with strong growth in Phone: (202) 224-5721 airline passengers, air cargo, general aviation, and flight www.blunt.senate.gov training. U.S. Senator Josh Hawley Springfield 901 E. St. Louis St., Suite 1604 Springfield, MO 65806 Phone: (417) 869-4433 Washington, DC B40A Dirksen Senate Office Building Washington, DC 20510 Phone: (202) 224-6154 www.hawley.senate.gov UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES U.S. Congressman Billy Long 7th District Springfield 3232 E. Ridgeview St. Springfield, MO 65804 Phone: (417) 889-1800 Washington, DC 2454 Rayburn House Office Building Washington, DC 20515 Phone: (202) 225-6536 www.long.house.gov For more information, please contact: Sandy Howard, Senior Vice President - Public Affairs [email protected] Emily Denniston, Vice President - Public Affairs [email protected] Springfield Area Chamber of Commerce 202 S. John Q. Hammons Parkway I Springfield, MO 65806 Phone: (417) 862-5567 www.springfieldchamber.com www.springfieldchamber.com The Chamber supports continued investment in all levels IMMIGRATION REFORM 2020 Legislative Priorities of public education and workforce training. -

2020 Election Analysis

Election2020 Analysis Current as of November 5, 11:00 a.m. TABLE OF CONTENT S 1 Introduction 2 117th Congress • Senate • House of Representatives • Reconciliation 3 Snapshot of Newly Elected Officials 4 Projected Committee Leadership 5 Committee Changes 6 Looking Toward 2022 INTRODUCTIO N While all election years are contentious to some degree, this one has been particularly so. Whatever the final outcome, post-election days result in raw feelings on one side and elation on the other. It is our hope that winners and losers alike – and all those who rooted for them – react with grace, a commitment to healing, and a firm resolve to maintain our Nation’s revered tradition of peaceful transition. Arizona: Holds a recount if the margin is < 0.1%. Georgia: No automatic recount; candidates can request a recount if the margin is < 1% Today many seats are still being Michigan: A candidate can petition for a recount decided, and with the razor thin if they allege “fraud or mistake in the canvass of the votes" within two days of the completion of the margins in many cases, we are keeping canvass of votes. A recount is automatic if the a close eye on the races that are yet to margin is equal or < 2,000 votes. Nevada: Any candidate can request a recount be decided, while digesting the decided and is responsible for the costs unless they are results and implications. With the declared the winner as a result of the recount. North Carolina: A candidate can request a possibility of vote recounts in the recount if the margin is < 0.5%, or 10,000 votes, presidential elections, please note the whichever is less.