An Update on Energy/Natural Resource Issues of Interest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2007 Heft 06-07.Pdf

Congress Report, Jahrgang 22 (2007), Heft 6-7 ___________________________________________________________________________ abgeschlossen am 9. Juli 2007 Seite 1. Reform des Einwanderungsrechts im Senat blockiert 1 2. Republikaner verhindern Vertrauensabstimmung über Justizminister 2 3. Senat spricht sich für verstärkte Nutzung erneuerbarer Energien aus 4 4. Repräsentantenhaus bewilligt Haushalt 2008 für Homeland Security 5 5. Repräsentantenhaus bewilligt Auslandshilfe 2008 6 6. Senatsausschuss verlangt Übergabe von offiziellen Dokumenten 7 7. Präsident ernennt Jim Nussle zum neuen Direktor des OMB 8 8. John Barrasso zum US-Senator für den Bundesstaat Wyoming ernannt 9 6-7/2007 Congress Report, Jahrgang 20 (2005), Heft 5 ___________________________________________________________________________ 2 Congress Report, ISSN 0935 - 7246 Nachdruck und Vervielfältigung nur mit schriftlicher Genehmigung der Redaktion. Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Congress Report, Jahrgang 22 (2007), Heft 6-7 ___________________________________________________________________________ 1. Reform des Einwanderungsrechts im Senat blockiert Im Senat hat am 28. Juni 2007 ein Antrag auf Ende der Debatte und Abstimmung über die anhängige Vorlage zur Reform des Einwanderungsrechts (vgl. CR 5/2007, S. 1) die notwendige 60-Stimmen-Mehrheit deutlich verfehlt . Damit ist die weitere parlamenta- rische Behandlung des von Präsident Bush unterstützten Gesetzgebungskompromisses bis auf weiteres blockiert. Für eine Beendigung der Debatte stimmten 46 Senatoren, dagegen sprachen sich 53 -

Season-Programws2.Pdf

Grant Support Cheyenne Kiwanis Foundation Kiwanis is a global organization of volunteers dedicated to changing the world one child and one community at a time. It is one of the largest community-service organizations dedicated primarily to helping the children of the world. The Cheyenne Kiwanis club was organized and charted on Janu- ary 22, 1922. The Cheyenne Kiwanis Foundation was founded on September 24, 1971 to be a vehicle by which individuals and clubs in the Cheyenne area could make tax-deductible contributions to further Kiwanis goals and purposes. The foundation provides services and support to the activities of the Cheyenne Kiwanis Club, The Rocky Mountain District and Kiwanis International. Every member of the Cheyenne Kiwanis Club is a member of the Cheyenne Kiwanis Foundation. Nine members of the Cheyenne Kiwanis Club are elected to serve on the foundation’s board of trustees on a revolving basis for three year terms. The Foundation has given to the Cheyenne community and the world including but not limited to Kiwanis International Worldwide Service Project to eliminate Iodine Deficiency Disorder (IDD) around the world, Youth Alternatives, NEEDS, Inc., YMCA, Boys and Girls Club of Cheyenne, HICAP, Attention Homes, CASA of Laramie County and Wyoming Leadership Seminar. Walmart The Walmart Foundation strives to provide opportunities that improve the lives of individuals in our communities including our customers and associates. Through financial contributions, in-kind donations and volunteerism, the Walmart Foundation supports initiatives focused on enhancing opportunities in our four main focus areas: · Education · Workforce Development · Economic Opportunity · Environmental Sustainability · Health and Wellness The Walmart Foundation has a particular interest in supporting the following populations: veterans and military families, traditionally under-served groups, individuals with disabilities and people impacted by natural disasters. -

Craig Thomas LATE a SENATOR from WYOMING ÷

m Line) Craig Thomas LATE A SENATOR FROM WYOMING ÷ MEMORIAL ADDRESSES AND OTHER TRIBUTES HON. CRAIG THOMAS ÷z 1933–2007 HON. CRAIG THOMAS ÷z 1933–2007 VerDate jan 13 2004 10:02 Nov 30, 2007 Jkt 036028 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6686 Sfmt 6686 C:\DOCS\CRAIG\36028.TXT CRS1 PsN: SKAYNE (Trim Line) (Trim Line) Craig Thomas VerDate jan 13 2004 10:02 Nov 30, 2007 Jkt 036028 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6687 C:\DOCS\CRAIG\36028.TXT CRS1 PsN: SKAYNE 36028.002 (Trim Line) (Trim Line) S. DOC. 110–5 Memorial Addresses and Other Tributes HELD IN THE SENATE AND HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OF THE UNITED STATES TOGETHER WITH A MEMORIAL SERVICE IN HONOR OF CRAIG THOMAS Late a Senator from Wyoming One Hundred Tenth Congress First Session ÷ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2007 VerDate jan 13 2004 10:02 Nov 30, 2007 Jkt 036028 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6686 C:\DOCS\CRAIG\36028.TXT CRS1 PsN: SKAYNE (Trim Line) (Trim Line) Compiled under the direction of the Joint Committee on Printing VerDate jan 13 2004 10:02 Nov 30, 2007 Jkt 036028 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 6687 Sfmt 6687 C:\DOCS\CRAIG\36028.TXT CRS1 PsN: SKAYNE (Trim Line) (Trim Line) CONTENTS Page Biography .................................................................................................. v Proceedings in the Senate: Tributes by Senators: Akaka, Daniel K., of Hawaii ..................................................... 54 Alexander, Lamar, of Tennessee ............................................... 27 Allard, Wayne, of Colorado ........................................................ 20 Barrasso, John, of Wyoming ..................................................... 104 Baucus, Max, of Montana .......................................................... 79 Bingaman, Jeff, of New Mexico ................................................ 29 Bond, Christopher S., of Missouri ............................................ -

APPENDIX: SMALL STATES FIRST - LARGE STATES LAST: the REPUBLICAN PLAN for REFORMING the PRESIDENTIAL PRIMARIES by Robert D

APPENDIX: SMALL STATES FIRST - LARGE STATES LAST: THE REPUBLICAN PLAN FOR REFORMING THE PRESIDENTIAL PRIMARIES by Robert D. Loevy Presented at the 2001 Annual Meeting Western Political Science Association Alexis Park Hotel Las Vegas, Nevada March 17, 2001 In the early fall of 1999, Jim Nicholson, the Chairman of the Republican National Committee, appointed a special committee to study the presidential primaries. The committee was officially titled the Advisory Commission on the Presidential Nominating Process. It was better known as the Brock Commission, named for the Advisory Commission chairperson, former Republican U.S. Senator Bill Brock of Tennessee.1 On December 13, 1999, the Advisory Commission held a public hearing at the headquarters of the Republican National Committee in Washington, D.C. Academic scholars from throughout the nation were invited to come and present their ideas and proposals for reforming the presidential primary process. The hearing was recorded 1 In addition to Bill Brock, who also was a former Chairperson of the Republican National Committee, the Advisory Commission included U.S. Senator Spencer Abraham, former National Chairperson Haley Barbour, Richard Bond, U.S. Representative Tom Davis, Frank Fahrenkopf, California Secretary of State Bill Jones, Oklahoma Governor Frank Keating, and Tom Sansonetti. Republican National Committee Chairperson Jim Nicholson was an ex officio member of the Advisory Commission. 1 by the C-SPAN television network and subsequently broadcast across the country. According to news reports, two major reform plans emerged from the public hearing. The first was the Rotating Regional Primary Plan proposed by the National Association of Secretaries of State (NASS). -

Congressional Record—Senate S6945

November 1, 2017 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S6945 The yeas and nays resulted—yeas 56, ics such as constitutional federalism popular wind, regardless of personal nays 42, as follows: and tort law, in addition to being a opinion. Whether considering the plain [Rollcall Vote No. 258 Ex.] clerk on the Supreme Court. She also meaning of a statute, discerning the YEA S—56 practiced commercial and appellate proper role of the courts, the legisla- Alexander Fischer Murkowski litigation at the Denver office of the tive branch, or the executive and its Barrasso Flake Paul national law firm Arnold and Porter. agencies, or evaluating the relation- Bennet Gardner Perdue She began her legal career as a clerk ships between the Federal Government Blunt Graham Portman to Judge Jerry E. Smith on the U.S. and the States, Justice Eid will side Boozman Grassley Risch Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. with what the law says, and she will do Burr Hatch Roberts Capito Heitkamp Rounds Her law experience took her to the U.S. it in that commonsense, western way Cassidy Heller Rubio Supreme Court under Clarence Thom- that clearly and articulately tells the Cochran Hoeven Sasse as. Prior to attending law school, Jus- Collins Inhofe American people what the law is. Scott Corker Isakson tice Eid was a special assistant and I am privileged to know Justice Eid. Shelby Cornyn Johnson speechwriter for the U.S. Secretary of I have known her for a number of years Strange Cotton Kennedy Education, Bill Bennett. She received now from my days as a student at the Crapo Lankford Sullivan Cruz Lee Thune her law degree from the University of University of Colorado School of Law Daines Manchin Tillis Chicago Law School, where she was the and through her work in the State of Donnelly McCain Toomey articles editor of the Law Review. -

Fall Defender.Indd

Clearwater Defender News of the Big Wild A Publication of Fall 2007, Vol. 4 No.6 Friends of the Clearwater Issued Quartely ORIGINAL RESEARCH Inside This Issue: Bill Berkowitz June 19, 2007 Original research J. Steven Griles did the crime but doesn’t Page 1 By bill berkowitz want to do the time Former Interior Department Deputy Secre- Motorized Madness Stopped tary who pleaded guilty earlier in connection by Forest Service at Meadow with Jack Abramoff looking for ‘sentence’ of Page 6 working for anti-environmental group instead Creek By gary macfarlane of five years in the pokey J. Steven Griles was convicted earlier this year of withholding information from the Senate In- FLOATING THE WILD dian Affairs Committee in 2005 about his meeting Page 8 SELWAY RIVER Jack Abramoff. Facing a possible five-year jail by Scott Phillips sentence, Griles has enlisted a small army of the well-connected who are petitioning the sentencing Judge for leniency, while Griles himself is ask- ing for community service -- part of which time Western Perspective: for would be served working with the American Rec- reation Coalition and the Walt Disney Company. Pageshifting 12 fire policy to be suc- Griles is scheduled for sentencing on June 26. cessful, it must include a The career lobbyist is the second-highest-level holistic view of wildfire Bush administration official to be caught up in the by will boyd ongoing Department of Justice investigation of former Republican Party uber-lobbyist, the cur- rently imprisoned Jack Abramoff. Griles, the for- mer Interior Deputy Secretary who, according to The Wolves Today SourceWatch, “oversaw the Bush administration’s Page 15by Sioux westervelt push to open more public land to energy develop- ment,” doesn’t think he deserves jail time. -

AAI RFA Endorsers

A partial list of endorsers of the Regulation Freedom Amendment GOVERNORS • Mike Pence, IN • Phil Bryant, MS • Matt Mead, WY STATE LEGISLATIVE LEADERS • NCSL (National Conference of State Legislators) President and UT Senate President Pro-Tem Curt • Bramble • CSG (Council of State Governments) immediate past National Chair and TN Senate Majority Leader • Mark Norris • ALEC (American Legislative Exchange Counsel) Immediate Past National Chair and TX State and Federal Power Committee Chair Rep. Phil King • TN Lt Gov/Senate President Ron Ramsey • TN Past CSG Chair and TN Senate Majority Leader Mark Norris • GA Senate President David Schafer • GA NCSL Former President Sen. Don Balfour • ID House Speaker Scott Bedke • IN Senate President David Long • IN House Speaker Brian Bosma • AR former Senate Majority Leader Sen. Eddie Joe Williams • KY Senate President Robert Stivers • KY House Majority Leader Rocky Adkins • KY House Natural Resources Chair Jim Gooch • MI Senate President Pro-Tem Tonya Shuitmaker • MO Former Senate President Tom Dempsey • NC House Majority Leader Mike Hager • ND Senate President Rich Wardner • ND House Majority Leader Al Carlson • ND House Judiciary Chair and former National CSG Chair Rep. Kim Koppelman • OH former House Speaker Pro-Tem Matt Huffman • PA Senate Finance Committee Chair John Eichelberger • SC Senate Labor Commerce and Industry Chair Thomas Alexander • TX ALEC National Chair and TX House State and Federal Power Committee Chair Phil King • UT Senate President Wayne Niederhauser • UT NCSL National Chair and -

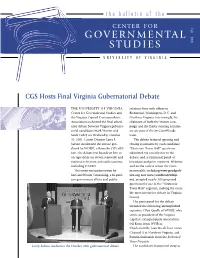

Governmental Studies and Richmond, Washington, D.C

the bulletin of the CENTER FOR Fall ı GOVERNMENTAL 2001 STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA CGS Hosts Final Virginia Gubernatorial Debate THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA relations firm with offices in Center for Governmental Studies and Richmond, Washington, D.C. and the Virginia Capitol Correspondents Northern Virginia. Interestingly, the Association co-hosted the final sched- chairmen of both the Warner cam- uled debate between Virginia guberna- paign and the Earley steering commit- torial candidates Mark Warner and tee are part of the McGuireWoods Mark Earley on Wednesday, October team. 10, 2001. Center Director Larry J. The debate featured opening and Sabato moderated the debate pro- closing statements by each candidate, duced by WDBJ7, a Roanoke CBS affil- “Electronic Town Hall” questions iate. The debate was broadcast live or submitted via e-mail prior to the on tape delay on eleven statewide and debate, and a traditional panel of national television and radio stations, broadcast and print reporters. Websites including C-SPAN. and media outlets across the Com- The event was underwritten by monwealth, including www.goodpoli- McGuireWoods Consulting, a bi-parti- tics.org and www.youthleadership. san government affairs and public net, accepted nearly 900 proposed questions for use in the “Electronic Town Hall” segment, making the event the most interactive debate in Virginia history. The press panel for the debate included the following accomplished reporters: Ellen Qualls of WDBJ7, who serves as president of the Virginia Capitol Correspondents Association; Jeff Kraus from WVIR in Charlottesville; Matt Brock from News Channel 8 in Northern Virginia; and Pamela Stallsmith from the Richmond Times-Dispatch. -

Symphonic Brilliance 55 Years of Life & Vibrancy

Symphonic Brilliance 55 Years of Life & Vibrancy Cheyenne Symphony Orchestra 2009-2010 Season Table of Contents Program Classic Conversations .....................................................................................................................................12 House Etiquette ..............................................................................................................................................14 Hausmusik Series ............................................................................................................................................16 September 19, 2009 ...................................Tchaikovsky Celebration ..............................................................20 October 10, 2009 .......................................Beethoven & Mendelssohn Epics.....................................................40 Educational Outreach .....................................................................................................................................50 November 21, 2009 Symphony Ball ...........Symphonic Brilliance ....................................................................52 January 23, 2010 ........................................Four Seasons .................................................................................56 February 27, 2010 ......................................Dvořák Cello Concerto ..................................................................64 April 24, 2010 ............................................Symphony & Opera In-Concert -

THE REPORT of the National Symposium on Presidential Selection

THE REPORT of the National Symposium on Presidential Selection THE CENTER FOR GOVERNMENTAL STUDIES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA 2001 THE REPORT of the National Symposium on Presidential Selection THE CENTER FOR GOVERNMENTAL STUDIES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA Copyright 2001 University of Virginia Center for Governmental Studies THE CENTER FOR GOVERNMENTAL STUDIES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA Founded in 1998 by Larry Sabato, the Center for Governmental Studies is dedicated to the proposition that government works better when politics works better. The Center is a non-partisan, public-interest institute with a three-part mission of political research, reform, and education. The Center is located in Charlottesville, Virginia, at the University founded by the same Thomas Jefferson who framed much of the American political system. The Center bridges the gap between the theory and the reality of politics with an innovative blend of lectures, forums, scholarly research, and community outreach. These efforts seek to explore politics past and present while maintaining a decidedly practical focus on the future. The annual conferences of the Governor’s Project, for example, consider the legacy of Virginia’s governors to preserve some hard-learned historical les- sons that may be applied today and by generations to come. Each December, the American Democracy Conference offers leading scholars, political players, journalists, and the general public an opportunity to assess the state of our democratic process. And the National Symposium Series brings together some of the most informed voices and brightest stars on the national scene to discuss a subject of particular relevance to the health of American politics. -

Roman Buhler Director, the Madison Coalition Thank You for The

Roman Buhler Director, The Madison Coalition Thank you for the opportunity to testify before the Committee today. I am the Director of the Madison Coalition, an organization dedicated to restoring a balance of state and federal power. America is in danger of adopting new style of government. In past years Presidents governed by working to pass laws in Congress. But in recent years it seems that some in the Executive Branch believe they can govern with regulatory edicts simply dictated from Washington. State legislators like you here in Kansas and around the nation have an opportunity to take a stand in support of a permanent end to "regulation without representation" and to help ensure that federal regulations, like federal laws, have the consent of the governed. We can no longer be satisfied with a government where bureaucrats dictate the rules that govern us. A bipartisan majority in the U.S. House of Representatives recently voted for a Bill called the REINS Act (Regulations from the Executive in Need of Scrutiny) to require that major new federal regulations be approved by Congress. But it is very unlikely that such a law could get the support of the necessary 60 votes in the U.S. Senate, even if America elected a President who would sign it. Furthermore, the constitutionality of such a law could be challenged in Court and, even if upheld, a law could be repealed or waived by a future Congress. An Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, on the other hand, could permanently rein in federal regulators and help to restore the checks and balances intended by the authors of our Constitution. -

Senate the Senate Met at 10 A.M

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 115 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 163 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 1, 2017 No. 177 Senate The Senate met at 10 a.m. and was NEW YORK CITY TERROR ATTACK The President will sign another CRA called to order by the President pro Mr. MCCONNELL. Mr. President, yes- resolution today, one that will over- tempore (Mr. HATCH). terday’s attack in Manhattan was sick- turn a regulation that threatened to drive up costs for millions of Ameri- f ening, twisted, and heartbreaking. The suspect appears to have been inspired cans who carry a credit card. It is a PRAYER by ISIL. We know that in the days regulation dreamed up by a govern- ahead, our intelligence community will ment agency, the CFPB, that claims to The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- make every effort to learn more about protect consumers but seems to have fered the following prayer: him and whether he had any connec- found a way to actually harm them. Let us pray. tion to this terror group and its hateful The Treasury Department released a Eternal and ever-blessed God, thank ideology. But today we are thinking of study showing how this regulation has You for waking us to see the light of everyone affected by this tragedy. We little to do with consumer protection this new day. Lord, on this All Saints’ are praying for the victims and their and everything to do with lining the Day, we remember the unseen cloud of families.