What Fish? Alexandra M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magazine SUMMER 2020 OCEANA.ORG

Magazine SUMMER 2020 OCEANA.ORG Oceana Senior Advisor Alexandra Cousteau and Bloomberg Philanthropies CEO Patti Harris are pictured at the Our Ocean 2019 conference in Oslo, Norway. For more, read the CEO Note on page 3. © Ilja C. Hendel Transparency Crusader (Sea) Food Security COVID-19 and Fisheries Renata Terrazas, Oceana’s VP in The ocean can feed a billion people, Dr. Daniel Pauly explains how fish Mexico, on publicizing vital data but who needs fish most? stocks could recover post-pandemic Board of Directors Ocean Council Oceana Staff Valarie Van Cleave, Chair Susan Rockefeller, Founder Andrew Sharpless Ted Danson, Vice Chair Kelly Hallman, Vice Chair Chief Executive Officer Diana Thomson, Treasurer Dede McMahon, Vice Chair Jim Simon James Sandler, Secretary Anonymous President Keith Addis, President Samantha Bass Gaz Alazraki Violaine and John Bernbach Jacqueline Savitz Chief Policy Officer, North America Monique Bär Rick Burnes Herbert M. Bedolfe, III Vin Cipolla Katie Matthews, Ph.D. Nicholas Davis Barbara Cohn Chief Scientist Sydney Davis Ann Colley César Gaviria Edward Dolman Matthew Littlejohn Senior Vice President, Strategic Initiatives Mária Eugenia Girón Kay and Frank Fernandez Loic Gouzer Carolyn and Chris Groobey Janelle Chanona Jena King J. Stephen and Angela Kilcullen Vice President, Belize Ben Koerner Ann Luskey Ademilson Zamboni, Ph.D. Sara Lowell Mia M. Thompson Vice President, Brazil Stephen P. McAllister Peter Neumeier Kristian Parker, Ph.D. Carl and Janet Nolet Joshua Laughren Daniel Pauly, Ph.D. Ellie Phipps Price Executive Director, Oceana Canada David Rockefeller, Jr. Maria Jose Peréz Simón Liesbeth van der Meer Susan Rockefeller David Rockefeller, Jr. Vice President, Chile Simon Sidamon-Eristoff Elias Sacal Rashid Sumaila, Ph.D. -

CBD Technical Series No. 87 Assessing Progress Towards Aichi Biodiversity Target 6 on Sustainable Marine Fisheries

Secretariat of the CBD Technical Series No. 87 Convention on Biological Diversity ASSESSING PROGRESS87 TOWARDS AICHI BIODIVERSITY TARGET 6 ON SUSTAINABLE MARINE FISHERIES CBD Technical Series No. 87 Assessing Progress towards Aichi Biodiversity Target 6 on Sustainable Marine Fisheries Serge M. Garcia and Jake Rice Fisheries Expert Group of the IUCN Commission of Ecosystem Management Published by the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity ISBN: 9789292256616 Copyright © 2020, Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views reported in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the Convention on Biological Diversity. This publication may be reproduced for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holders, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. The Secretariat of the Convention would appreciate receiving a copy of any publications that use this document as a source. Citation Garcia, S.M. and Rice, J. 2020. Assessing Progress towards Aichi Biodiversity Target 6 on Sustainable Marine Fisheries. Technical Series No. 87. Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Montreal, 103 pages For further information, please contact: Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity World Trade Centre 413 St. Jacques Street, Suite 800 Montreal, Quebec, Canada H2Y 1N9 Phone: 1(514) 288 2220 Fax: 1 (514) 288 6588 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.cbd.int This publication was made possible thanks to financial assistance from the Government of Canada. -

The Role of Reservations and Vetoes in Marine Conservation Agreements

The Role of Reservations and Vetoes in Marine Conservation Agreements Howard S. Schiffman A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Professor Robin R. Churchill, Supervisor Cardiff Law School Cardiff University Submitted, July 3, 2006 \ ~ . lv UMI Number: U585553 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U585553 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Role of Reservations and Vetoes in Marine Conservation Agreements Howard S. Schiffman Contents Preface...................................................................................................................iv Acknowledgements ..............................................................................................v List of Abbreviations ...........................................................................................viii Chapter 1 “Exemptive Provisions:” A Survey of the Issues in International Law 1 I. Introduction ............................................................................................ -

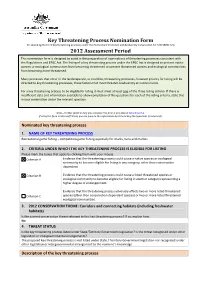

Key Threatening Process Nomination Form

Key Threatening Process Nomination Form for amending the list of key threatening processes under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) 2012 Assessment Period This nomination form is designed to assist in the preparation of nominations of threatening processes consistent with the Regulations and EPBC Act. The listing of a key threatening process under the EPBC Act is designed to prevent native species or ecological communities from becoming threatened or prevent threatened species and ecological communities from becoming more threatened. Many processes that occur in the landscape are, or could be, threatening processes, however priority for listing will be directed to key threatening processes, those factors that most threaten biodiversity at national scale. For a key threatening process to be eligible for listing it must meet at least one of the three listing criteria. If there is insufficient data and information available to allow completion of the questions for each of the listing criteria, state this in your nomination under the relevant question. Note – Further detail to help you complete this form is provided at Attachment A. If using this form in Microsoft Word, you can jump to this information by Ctrl+clicking the hyperlinks (in blue text). Nominated key threatening process 1. NAME OF KEY THREATENING PROCESS Recreational game fishing – competition game fishing especially for sharks, tuna and marlins 2. CRITERIA UNDER WHICH THE KEY THREATENING PROCESS IS ELIGIBLE FOR LISTING Please mark the boxes that apply by clicking them with your mouse. Criterion A Evidence that the threatening process could cause a native species or ecological community to become eligible for listing in any category, other than conservation dependent. -

California Spiny Lobster Fishery Management Plan and Proposed Regulatory Amendments

Final Initial Study/Negative Declaration California Spiny Lobster Fishery Management Plan and Proposed Regulatory Amendments PREPARED FOR: California Fish and Game Commission 1416 Ninth Street, Suite 1320 Sacramento, CA 95814 Contact: Tom Mason California Department of Fish and Wildlife Senior Environmental Scientist PREPARED BY: Ascent Environmental, Inc. 455 Capitol Mall, Suite 300 Sacramento, CA 95814 Contact: Curtis E. Alling, AICP Michael Eng March 2016 Cover Photo: Courtesy of California Department of Fish and Wildlife 15010103.01 COMMENTS AND RESPONSES TO COMMENTS This chapter of the Final Initial Study/Negative Declaration (Final IS/ND) contains the comment letters received during the 45-day public review period for the Draft Initial Study/Negative Declaration (Draft IS/ND), which commenced on January 21, 2016 and closed on March 7, 2016. The Notice of Completion was provided to the State Clearinghouse on January 21, 2016 and the IS/ND was circulated to the appropriate state agencies. COMMENTERS ON THE DRAFT IS/ND Table 1 below indicates the numerical designation for the comment letters received, the author of the comment letter, and the date of the comment letter. Comment letters have been numbered in the order they were received by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW). Table 1 List of Commenters Letter Agency/Organization/Name Date 1 Native American Heritage Commission February 8, 2016 2 William Barnett January 29, 2016 3 Ken Kurtis, Reef Seekers Dive Co. January 31, 2016 4 A. Talib Wahab, Avicena Network, Inc. March 6, 2016 5 Center for Biological Diversity March 7, 2016 6 Christopher Miller March 7, 2016 COMMENTS AND RESPONSES ON THE DRAFT IS/ND The written comments received on the Draft IS/ND and the responses to those comments are provided in this chapter of the Final IS/ND. -

Ecological Change in the Oceans and the Role of Fisheries

Ecological Change in the Oceans and the Role of Fisheries Boris Worm Department of Biology, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada When I took a course with Elisabeth Mann Borgese in 1999, she reminded us that the oceans are constantly changing, both in their outer appearance, and their internal workings. Constant ecological change makes the ocean fascinat- ing to observe and study, but challenging to understand and manage. Long-term changes are brought about by geological processes such as sedi- ment transport, volcanism, and plate tectonics that affect the very shape of ocean basins and the extent of habitat features such as shallow shelf seas con- ducive to biological productivity. On intermediate time scales, climate-driven changes in ocean temperature, circulation, and chemistry can have profound ecological effects on the abundance and distribution of marine life forms, and even caused massive extinction events in the past. Over the last few thousand years, however, people have gradually become a dominant agent of change in the oceans. Initially tied to the continents where we evolved, human hunters at least 42,000 years ago started to venture out into the ocean to pursue large fish.1 Driven by changes in fishing technology, human population size, and global trade, this role has been extending to all ocean basins, and even parts of the deep sea. Over the last two decades, the profound ecological change brought about by human activities has also been studied in detail by the sci- entific community. Although human impacts on ocean ecosystems involve many pathways, there is little doubt that fishing— defined here as any extraction of marine animals and plants—is the activity that historically has had the most trans- formative ecological effects.2 Although it is not clear how much marine life has been removed over the entire history of fishing, recent total catches likely 1 S. -

Let Us Eat Fish

Let Us Eat Fish By RAY HILBORN Published: April 14, 2011 Yuko Shimizu THIS Lent, many ecologically conscious Americans might feel a twinge of guilt as they dig into the fish on their Friday dinner plates. They shouldn’t. Over the last decade the public has been bombarded by apocalyptic predictions about the future of fish stocks — in 2006, for instance, an article in the journal Science projected that all fish stocks could be gone by 2048. Subsequent research, including a paper I co-wrote in Science in 2009 with Boris Worm, the lead author of the 2006 paper, has shown that such warnings were exaggerated. Much of the earlier research pointed to declines in catches and concluded that therefore fish stocks must be in trouble. But there is little correlation between how many fish are caught and how many actually exist; over the past decade, for example, fish catches in the United States have dropped because regulators have lowered the allowable catch. On average, fish stocks worldwide appear to be stable, and in the United States they are rebuilding, in many cases at a rapid rate. The overall record of American fisheries management since the mid-1990s is one of improvement, not of decline. Perhaps the most spectacular recovery is that of bottom fish in New England, especially haddock and redfish; their abundance has grown sixfold from 1994 to 2007 . Few if any fish species in the United States are now being harvested at too high a rate, and only 24 percent remain below their desired abundance . Much of the success is a result of the Magnuson Fishery Conservation and Management Act , which was signed into law 35 years ago this week. -

Evolutionary Consequences of Fishing and Their Implications For

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) Evolutionary Applications ISSN 1752-4571 SYNTHESIS Evolutionary consequences of fishing and their implications for salmon Jeffrey J. Hard,1 Mart R. Gross,2 Mikko Heino,3,4,5 Ray Hilborn,6 Robert G. Kope,1 Richard Law7 and John D. Reynolds8 1 Conservation Biology Division, Northwest Fisheries Science Center, Seattle, WA, USA 2 Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada 3 Department of Biology, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway 4 Institute of Marine Research, Bergen, Norway 5 Evolution and Ecology Program, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), Laxenburg, Austria 6 School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA 7 Department of Biology, University of York, York, UK 8 Department of Biological Sciences, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, Canada Keywords Abstract adaptation, fitness, heritability, life history, reaction norm, selection, size-selective We review the evidence for fisheries-induced evolution in anadromous salmo- mortality, sustainable fisheries. nids. Salmon are exposed to a variety of fishing gears and intensities as imma- ture or maturing individuals. We evaluate the evidence that fishing is causing Correspondence evolutionary changes to traits including body size, migration timing and age of Jeffrey J. Hard, Conservation Biology Division, maturation, and we discuss the implications for fisheries and conservation. Few Northwest Fisheries Science Center, 2725 studies have fully evaluated the ingredients of fisheries-induced evolution: selec- Montlake Boulevard East, Seattle, WA 98112, USA. Tel.: (206) 860 3275; fax: (206) 860 tion intensity, genetic variability, correlation among traits under selection, and 3335; e-mail: [email protected] response to selection. -

Foundations of Fisheries Science

Foundations of Fisheries Science Foundations of Fisheries Science Edited by Greg G. Sass Northern Unit Fisheries Research Team Leader Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Escanaba Lake Research Station 3110 Trout Lake Station Drive, Boulder Junction, Wisconsin 54512, USA Micheal S. Allen Professor, Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences University of Florida 7922 NW 71st Street, PO Box 110600, Gainesville, Florida 32653, USA Section Edited by Robert Arlinghaus Professor, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin and Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries Department of Biology and Ecology of Fishes Müggelseedamm 310, 12587 Berlin, Germany James F. Kitchell A.D. Hasler Professor (Emeritus), Center for Limnology University of Wisconsin-Madison 680 North Park Street, Madison, Wisconsin 53706, USA Kai Lorenzen Professor, Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences University of Florida 7922 NW 71st Street, P.O. Box 110600, Gainesville, Florida 32653, USA Daniel E. Schindler Professor, Aquatic and Fishery Science/Department of Biology Harriett Bullitt Chair in Conservation University of Washington Box 355020, Seattle, Washington 98195, USA Carl J. Walters Professor, Fisheries Centre University of British Columbia 2202 Main Mall, Vancouver, British Columbia V6T 1Z4, Canada AMERICAN FISHERIES SOCIETY BETHESDA, MARYLAND 2014 A suggested citation format for this book follows. Sass, G. G., and M. S. Allen, editors. 2014. Foundations of Fisheries Science. American Fisheries Society, Bethesda, Maryland. © Copyright 2014 by the American Fisheries Society All rights reserved. Photocopying for internal or personal use, or for the internal or personal use of specific clients, is permitted by AFS provided that the appropriate fee is paid directly to Copy- right Clearance Center (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, Massachusetts 01923, USA; phone 978-750-8400. -

Marine Biodiversity: Responding to the Challenges Posed by Climate Change, Fisheries, and Aquaculture

e Royal Society of Canada Expert Panel Sustaining Canada’s Marine Biodiversity: Responding to the Challenges Posed by Climate Change, Fisheries, and Aquaculture REPORT February 2012 Prof. Isabelle M. Côté Prof. Julian J. Dodson Prof. Ian A. Fleming Prof. Je rey A. Hutchings (Chair) Prof. Simon Jennings Prof. Nathan J. Mantua Prof. Randall M. Peterman Dr. Brian E. Riddell Prof. Andrew J. Weaver, FRSC Prof. David L. VanderZwaag SUSTAINING CANADIAN MARINE BIODIVERSITY An Expert Panel Report on Sustaining Canada's Marine Biodiversity: Responding to the Challenges Posed by Climate Change, Fisheries, and Aquaculture Prepared by: The Royal Society of Canada: The Academies of Arts, Humanities and Sciences of Canada February 2012 282 Somerset Street West, Ottawa ON, K2P 0J6 • Tel: 613-991-6990 • www.rsc-src.ca | 1 Members of the Expert Panel on Sustaining Canadian Marine Biodiversity Isabelle M. Côté, Professor, Department of Biological Sciences, Simon Fraser University Julian J. Dodson, Professeur titulaire, Département de biologie, Université Laval Ian A. Fleming, Professor, Ocean Sciences Centre, Memorial University of Newfoundland Jeffrey A. Hutchings, Killam Professor and Canada Research Chair in Marine Conservation and Biodiversity, Department of Biology, Dalhousie University Panel Chair Simon Jennings, Principal Scientist, Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (CEFAS), Lowestoft, UK, and Honorary Professor of Environmental Sciences at the University of East Anglia, UK Nathan J. Mantua, Associate Research Professor, Aquatic and Fisheries Sciences, University of Washington, USA Randall M. Peterman, Professor and Canada Research Chair in Fisheries Risk Assessment and Management, School of Resource and Environmental Management, Simon Fraser University Brian E. Riddell, PhD, CEO, Pacific Salmon Foundation, Vancouver, British Columbia Andrew J. -

Electronic Green Journal Volume 1, Issue 43

Electronic Green Journal Volume 1, Issue 43 Review: Ocean Recovery: A Sustainable Future for Global Fisheries? By R. Hilborn and U. Hilborn Reviewed by Byron Anderson DeKalb, Illinois, USA Hilborn, Ray and Hilborn, Ulrike. Ocean Recovery: A Sustainable Future for Global Fisheries? New York, New York, USA: Oxford University Press, 2019; xii, 196pp. ISBN: 9780198839767, hardcover, US $37.95. Managed ocean fisheries provide about half of global fish production. Fish stocks are largely dependent on fisheries management, and fish are important to global food security. While many individuals and organizations lament the decline of fish, the truth is that oceans still contain a lot of fish and fish stocks are not declining. Ocean Recovery: A Sustainable Future for Global Fisheries? by Ray Hilborn and Ulrike Hilborn presents an overview of how fisheries are managed and counters misconceptions about fisheries management, the status and sustainability of fish stocks, and the relative cost of catching fish in the ocean when compared with producing food from the land. A common misunderstanding, for example, is that overfishing causes a termination of the bounty of fish. While fish stocks can experience a temporary decline, fishing pressure subsides and stocks rebuild, though some can take years to do so. Environmental impacts of fishing are considered. For example, if a person stops eating fish, they may be likely to turn to beef, chicken, or pork, sources of food that are significantly more damaging on the environment. However, vegetarian and vegan diets are not discussed as potential alternatives to eating fish. Other topics covered include fisheries sustainability and management, recreational and fresh water fisheries, seafood certification, ecosystem-based management, and allocating fishing boundaries. -

When Monopoly Harvester Co-Ops Are Preferred to a Rent Dissipated Resource Sector

Are Two Rents Better than None? When Monopoly Harvester Co-ops are Preferred to a Rent Dissipated Resource Sector Dale T. Manning1 Colorado State University [email protected] Hirotsugu Uchida2 University of Rhode Island [email protected] Draft May 10, 2014 Selected Paper prepared for presentation at the Agricultural & Applied Economics Association’s 2014 AAEA Annual Meeting, Minneapolis, MN, July 27-29, 2014. Copyright 2014 by D.T. Manning and H. Uchida. All rights reserved. Readers may make verbatim copies of this document for non-commercial purposes by any means, provided that this copyright notice appears on all such copies. 1 Assistant professor, Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, Colorado State University, [email protected]. 2 Assistant professor, Department of Environmental and Natural Resource Economics, University of Rhode Island, [email protected]. Abstract This paper evaluates the conditions under which a fish-harvester cooperative (co-op) with monopoly power represents a preferable outcome when compared to a rent dissipated fishery. Currently, United States anti-trust law prevents harvesters from coordinating to restrict output. In a fishery, this coordination can represent an improvement, despite the creation of market power because a monopolist builds the resource stock. We show, analytically, how a monopolist harvester co-op generates both resource and monopoly rent. While the monopolist generates monopoly rent by restricting production to generate higher prices, it also manages the fish stock to lower stock dependent harvesting costs. We demonstrate the conditions under which a monopoly is likely to be favored over rent dissipation. Given that a monopoly can be efficiency- improving in a common property resource sector, policymakers should consider both the costs and benefits of co-op formation in the case of a rent dissipated fishery.