Island Here Today, Gone Tomorrow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baltimore County Visitor's Guide

VISITORS GUIDE EnjoyBaltimoreCounty.com Crab Cake Territory | Craft Beer Destination PAPPASPAPPAS RESTAURANTRESTAURANT&: & SPORTSSPORTS BARBAR Ship our famous crab cakes nationwide: 1-888-535-CRAB (2722) or www.PappasCrabCakes.com Oprah’s Favorite Crab Cake OPENING BALTIMORE RAVENS SEASON 2018 Pappas Seafood Concession Stand inside M&T Bank Stadium’s lower level! CHECK OUT PAPPAS AT MGM NATIONAL HARBOR AND HOLIDAY INN INNER HARBOR PAPPAS MGM 301-971-5000 | PAPPAS HOLIDAY INN 410-685-3500 PARKVILLE COCKEYSVILLE GLEN BURNIE PAPPAS 1725 Taylor Avenue 550 Cranbrook Rd. 6713 Governor Ritchie Hwy SEAFOOD COMPANY Parkville, MD 21234 Cockeysville, MD 21030 Glen Burnie, MD 21061 1801 Taylor Avenue 410-661-4357 410-666-0030 410-766-3713 Parkville, MD 21234 410-665-4000 PARKVILLE & COCKEYSVILLE LOCATIONS Less than fi ve miles Serving carry out Private Dining available: 20–150 ppl. from BWI Airport! steamed crabs year round! 2 EnjoyBaltimoreCounty.com Featuring farm brewed beers from Manor Hill Brewing, brick oven pizzas, and other seasonal offerings in Old Ellicott City. • Manor Hill Tavern is a roud th family owned V t · p part of e plenty .. 1c oria Restaurant Group. Columbia. MD Clarksville. MD v1ctoriagas-tropub com foodplenty com EnjoyBaltimoreCounty.com 3 ENJOYr.AI, .. #,, BALTIMORE~~ CONTENTS ON THE COVER: Boordy Vineyards Located in northern Baltimore County 8 Celebrate With Us in the Long Green Valley, Boordy Vine- yards is Maryland’s oldest family-run winery, having been established in 12 The Arts for Everyone 1945. Boordy is owned and operated by the Deford family, for whom “grow- 14 Wine Country ing and making wine is our life and our pleasure.” Boordy reigns as a leading winery in the region. -

System Map Agency of Central Maryland Effective: July 2018 Schematic Map Not to Scale Serving: Howard County, Anne Arundel County

70 70 Millennium RIDGE RD Heartlands Patapsco TOWN AND Valley ELLICOTT Walmart State COUNTRY BLVD ROGERS AVE Chatham St. Johns Normandy Park Baltimore National Pike N. Chatham Rd Plaza Plaza CITY Shopping Center 40 40 405 DOWNTOWN BALTIMORE NATIONAL PIKE 150 40 150 150 BALTIMORE 405 Park Howard County Lott View Court House Frederick Rd PLUM TREE DR FREDERICK DR Plaza Apts 310 JOHNS HOPKINS 144 405 HOSPITAL MAIN ST DOWNTOWN Homewood Rd 320 BALTIMORE 150 Oella CATONSVILLE Old Annapolis Rd Miller Library St. Johns Ln 315 Historic Main St TOLL HOUSE RD Ellicott City Centennial Ln Old Annapolis Rd 405 Centennial Lake B&O Railroad Shelbourne New Cut Rd Station Museum Patapsco River DORSEY House 150 Clarksville Pike Clarksville Pike HALL DR OLD COLUMBIA 108 108 PIKE 95 Cedar Dorsey Long Gate Lane Search Shopping Park Center 320 29 150 Columbia 310 Sports Park COLUMBIA RD 405 166 Meadowbrook ILCHESTER Harpers Farm Rd Harper’s Bain COLUMBIA PIKE LONG GATE Choice Senior Ctr. Park PKWY OLD ANNAPOLIS RD Long Gate to Camden Station Bryant 405 405 HARPERS TWIN RIVERS 150 Wilde Lake Montgomery Rd Sheppard Ln 325 FARM RD Woods PATUXENT RD LITTLE 315 335 401 GOVERNOR PKWY 150 345 Patapsco Valley State Park Wilde WARFIELD PKWY Lake 195 TWIN RIVERS RED BRANCH RD LYNX LN Lake to Perryville 325 401 LITTLE PATUXENT Columbia Kittamaqundi CEDAR LN PKWY Mellenbrook Rd Centre Swim Columbia Mall 405 310 406 Park Center RD 407 Columbia Medical St. Denis 325 408 Center 108 404 LITTLE PATUXENT PKWY KNOLL DR Howard County Howard Merriweather Thunder Hill Rd to Baltimore -

Patapsco Valley State Park Hunting Areas

Patapsco Valley State Park Hunting Areas Legend Carroll County County Boundary Hunting Area Boundary Area 2 Area 3 Area 11 Area 1 Area 16 Area 4 Area 5 Baltimore County Area 6 ± Howard County Area 12 Area 8 Area 7 Carroll Area 15 Baltimore Area 14 Area 13 Howard Wildlife & Heritage Service Location within Maryland 3740 Gwynnbrook Avenue MD iMAP, SHA Owings Mills, Maryland 21117 410-356-9272 (hunting questions) 01.25 2.5 5 Miles 410-461-5005 (Park Headquarters) Morgan Run Natural Environment Area Westminster, Maryland (Carroll County) Area 9 Old Washington Road Area 10 Ben Rose Lane ± Area 17 Cherry Tree Lane Liberty Reservoir MD iMAP, SHA Legend Hunting Area Boundary ^ Location within Wildlife & Heritage Service Carroll County 3740 Gwynnbrook Avenue Owings Mills, Maryland 21117 410-356-9272 (hunting questions) 00.75 1.5 3 Miles 410-461-5005 (Park Headquarters) Raincliff Road 1 Gorsuch Road Switch Henryton Road 2 1 Henryton Road 3 4 Road River 5 5 Road arriotsville **Boundaries are approximate. Look for signs in the field.** **Boundaries are approximate. Look for signs in the field.** 6 RoadDriver Sign In Here For Area 12 12 8 7 **Boundaries are approximate. Look for signs in the field.** 15 13 **Boundaries are approximate. Look for signs in the field.** Patapsco Valley State Park - Henryton Area 3 Marriotsville, Maryland (Carroll County) ***Boundaries are approximate. Look for signs in the field.*** Henryt on Road Marriotsville Rd i N umbe r 2 ver psco Ri n n ta o t y nch Pa Bra nter Rd nter uth So Ce Henr i Road = le il tsv Location within Carroll County Marrio Legend = Occupied Dwelling Pines Rivers and Streams ^ i Parking Area Fields Railroad Tracks Mixed Forest Trails Roads Hunting Area Boundary ± 20ft Contours Wildlife and Heritage Service 3740 Gwynnbrook Avenue 00.125 0.25 0.5 Miles Owings Mills, Maryland 21117 410-356-9272 Patapsco Valley State Park - Mercer Property Area 11 Woodbine, Maryland (Carroll County) Location within ***Boundaries are approximate. -

The Patapsco Regional Greenway the Patapsco Regional Greenway

THE PATAPSCO REGIONAL GREENWAY THE PATAPSCO REGIONAL GREENWAY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS While the Patapsco Regional Greenway Concept Plan and Implementation Matrix is largely a community effort, the following individuals should be recognized for their input and contribution. Mary Catherine Cochran, Patapsco Heritage Greenway Dan Hudson, Maryland Department of Natural Resources Rob Dyke, Maryland Park Service Joe Vogelpohl, Maryland Park Service Eric Crawford, Friends of Patapsco Valley State Park and Mid-Atlantic Off-Road Enthusiasts (MORE) Ed Dixon, MORE Chris Eatough, Howard County Office of Transportation Tim Schneid, Baltimore Gas & Electric Pat McDougall, Baltimore County Recreation & Parks Molly Gallant, Baltimore City Recreation & Parks Nokomis Ford, Carroll County Department of Planning The Patapsco Regional Greenway 2 THE PATAPSCO REGIONAL GREENWAY TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................4 2 BENEFITS OF WALKING AND BICYCLING ...............14 3 EXISTING PLANS ...............................................18 4 TREATMENTS TOOLKIT .......................................22 5 GREENWAY MAPS .............................................26 6 IMPLEMENTATION MATRIX .................................88 7 FUNDING SOURCES ...........................................148 8 CONCLUSION ....................................................152 APPENDICES ........................................................154 Appendix A: Community Feedback .......................................155 Appendix B: Survey -

CR40-2020Public

County Council Of Howard County, Maryland 2020 Legislative Session Legislative Day No. 3 Resolution No. 40 -2020 Introduced by: The Chairperson at the request of the County Executive and cosponsored by Liz Walsh A RESOLUTION endorsing an application by the Patapsco Heritage Greenway, Inc. to the Maryland Heritage Area Authority for approval of amendments to the Patapsco Valley Heritage Area boundaries. introduced and read first time ^-^ 2 _> 2020. By order 'f^^^^y^,^ ^^ Diane Schwartz Jones,'ft.dministrator Read for a second time at a pubiic hearing on i^lfi _, 2020. ^ ^ By order f\^t^/^^^ /^ Diane Schwartz JoriSs, Administrator This Resolution was read the third time and was Adopted_, Adopted with amendment^., Failed_, Withdrawn_, by the County Council ^ on /t^wY K? _, 2020. Certified1 By ^^'^^.^J^^ ^ ^ Diane Schwartz Jone&^dministrator Appuived by the Co\mty Executive U'k.^J./^'i. V, _ 2020 Calvin Bai^Connjy''@xecutive NOI'E; [[text in brdckets]} indicates deletions from existing law, TEXT IN SMALL CAPITALS indicates additions to existing law, Strit indicates materiai dsieted by ametidinent; .UnderEiinn^ indicates material added by amendment 1 WHEREAS, the Patapsco Valley Heritage Area is a Maryland Heritage Area, that seeks 2 to promote heritage tourism in the Patapsco Valley through historic, environmental and 3 recreational programs and partnerships; and 4 5 WHEREAS, Maryland's Heritage Areas are locally designated and state certified 6 regions where public and private partners make commitments to preserving and enhancing 7 historic, cultural and natural resources for sustamable economic development through heritage 8 tourism; and 9 10 WHEREAS) PlanHo^ard 2030, the general plan for Howard County, was amended in 11 2015, via CB 18-2015 to incorporate the Patapsco Heritage Area Management Plan, as approved 12 by the Maryland Heritage Area Authority; and 13 14 WHEREAS, the portion of the Patapsco Valley included in the approved Patapsco 15 Heritage Area includes historic sites and communities. -

For Sublease

1306 Concourse Drive, Lithicum, MD 21090 Anne Arundel County WOODLANDS PARK (BUILDING NO. 3) j UV32 UV125 Lochearn Alpha Ridge Park Patapsco Valley State Park ¦¨§695 ¦¨§70 j j Woodlawn Leakin Park FOR70 SUBLEASE ¦¨§ j West Friendship Park j PROPERTY HIGHLIGHTS: David W Force Park £¤40 j Suite Highlights • Class A Office Park With Ideal Location to BWI Catonsville UV144 Ellicott City ¦¨§95 • Available: Suite 350; +2,919 SF £¤29 Patapsco Valley State Park University of MD • Parking Ratio: 4/1,000 SF Hilton Baltimore County j Arbutus • Term Remaining: Through 12/2023 Centennial Parkj Patapsco Valley State Park Avalon Building Highlights j SITE 29 Rockburn Branch Park • Five-story office building totaling 115,557 SF Blandair Park j ¦¨§895 Natural Resource Man Area j j Columbia • Easy Access to MD Route 295 and I-695; minutes from Elkridge ¨95 Baltimore City, Fort Meade, and Columbia ¦§ UV108 • On-site Property Management UV32 100 BALTIMORE/WASHINGTON • 24/7 key fob access INTERNATIONAL THURGOOD MASHALL AIRPORT Johns Hopkins University Nearby Amenities Applied Physics j Savage Park UV100 £¤29 North Laurel j UV295 Steele Stanwick Jesse Schwartzman 9881 Broken Land Parkway, Suite 300 [email protected] [email protected] Columbia, MD 21046 443-574-1420 443-632-2067 klnb.com 1306 CONCOURSE DR Linthicum, MD 21090 I Anne Arundel County FLOOR PLAN | SUITE 350 NUMBERED NOTES: SUITE 350 -+ 2,919 SF KEY PLAN Steele Stanwick Jesse Schwartzman [email protected] [email protected] 443-574-1420 443-632-2067 PHOTOS LOBBY / ELEVATORS COMMON AREA CONFERENCE -

Assessing the Rockburn Branch Subwatershed of the Lower Patapsco River for Restoration Opportunities

Assessing the Rockburn Branch Subwatershed of the Lower Patapsco River for Restoration Opportunities Prepared for: Howard County, Maryland Department of Public Works Bureau of Environmental Services NPDES Watershed Management Program Prepared by: JoAnna Lessard and Sam Stribling, Tt In cooperation with: Sally Hoyt, Paul Sturm and Emily Corwin, CWP January 23, 2006 Final Draft Table of Contents Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...........................................................................................................v SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................1 1.1 Background .....................................................................................................................1 1.2 Study Purpose and Scope ...............................................................................................1 1.3 Rockburn Branch Subwatershed Description .............................................................2 1.4 Additional Studies and Technical Information............................................................2 1.4.1 Impervious Area Assessment...............................................................................2 1.4.2 Stream Monitoring Study Results .......................................................................3 SECTION 2: PROBLEM IDENTIFICATION...........................................................................7 2.1 Stream Corridor Assessment for Rockburn Branch...................................................7 -

The Patapsco Forest Reserve: Establishing a “City Park” for Baltimore, 1907-1941

87 RESEARCH ARTICLES The Patapsco Forest Reserve: Establishing a “City Park” for Baltimore, 1907-1941 Geoffrey L. Buckley, Robert F. Bailey, and J. Morgan Grove THE PATAPSCO My own – my native river, Thou flashest to the day – And gatherest up thy waters In glittering array; The spirits of thy bosom Are waking from their rest, And O! their shouts are banishing Sad feelings from my breast. From Charles Soran, The Patapsco and Other Poems, Third Edition, with Additions. (Baltimore: Printed by Sherwood & Co., 858) n 897, a contributor to the editorial pages of the Baltimore News informed readers that Baltimore had “but one great park.” Rather than lavish praise on Druid Hill Park, however, the editorialist chose Ito draw attention to the “undeveloped condition” of the city’s other parks. After taking the mayor to task for ignoring the problem and accusing the city of “wastefulness, neglect and bad management,” the writer concluded: “The parks of our city should be for the people – all the people – not for a particular class, or for those living in a particular district. Park pleasures and benefits should be available to all, and when a city grows as large as Baltimore now is it is self-evident that one park will not do for all. We should have a series of parks adequate to the wants of Geoffrey L. Buckley is Associate Professor ofin Geography at Ohio University in Athens, OH. Robert F. Bailey is with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources. J. Morgan Grove is a Research Forester at the USDA Forest Service Northeastern Forest Experiment Station in South Burlington, VT. -

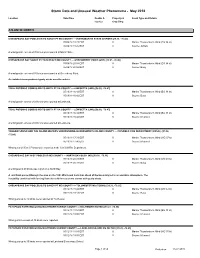

Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena - May 2018

Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena - May 2018 Location Date/Time Deaths & Property & Event Type and Details Injuries Crop Dmg ATLANTIC NORTH CHESAPEAKE BAY POOLES IS TO SANDY PT MD COUNTY --- (KMTN)MARTIN STATE AIRPORT [39.33, -76.42] 05/04/18 19:25 EST 0 Marine Thunderstorm Wind (EG 34 kt) 05/04/18 19:25 EST 0 Source: AWOS A wind gust in excess of 30 knots was reported at Martin State. CHESAPEAKE BAY SANDY PT TO N BEACH MD COUNTY --- GREENBERRY POINT (GBY) [38.97, -76.46] 05/04/18 20:04 EST 0 Marine Thunderstorm Wind (EG 34 kt) 05/04/18 20:04 EST 0 Source: Buoy A wind gust in excess of 30 knots was reported at Greenberry Point. An isolated storm produced gusty winds over the waters. TIDAL POTOMAC COBB IS MD TO SMITH PT VA COUNTY --- LEWISETTA (LWS) [38.00, -76.47] 05/10/18 16:42 EST 0 Marine Thunderstorm Wind (EG 34 kt) 05/10/18 16:42 EST 0 Source: Buoy A wind gust in excess of 30 knots was reported at Lewisetta. TIDAL POTOMAC COBB IS MD TO SMITH PT VA COUNTY --- LEWISETTA (LWS) [38.00, -76.47] 05/10/18 16:42 EST 0 Marine Thunderstorm Wind (EG 34 kt) 05/10/18 16:42 EST 0 Source: Mesonet A wind gust in excess of 30 knots was reported at Lewisetta. TANGIER SOUND AND THE INLAND WATERS SURROUNDING BLOODSWORTH ISLAND COUNTY --- CRISFIELD FIRE DEPARTMENT (CRSFL) [37.98, -75.86] 05/10/18 17:33 EST 0 Marine Thunderstorm Wind (MG 37 kt) 05/10/18 17:40 EST 0 Source: Mesonet Wind gusts of 35 to 37 knots were reported at the Crisfield Fire Department. -

Trip Schedule

Mountain Club of Maryland Trip Schedule NOVEMBER, 2008 – FEBRUARY, 2009 The Mountain Club of Maryland is a non-profit organiza- Trail Policies and Etiquette tion, founded in 1934, whose primary concern is to provide its The Club is dependent upon the voluntary cooperation of members and friends with the opportunity to enjoy nature those participating in its activities. Observance of the following through hiking, particularly in the mountainous areas accessible guidelines will enhance the enjoyment of everyone. to Baltimore. We publish a schedule of hikes, including a variety to please 1. Register before the deadline–unless otherwise specified, no every taste. Our trips vary in length and difficulty, and include later than 9 pm the night before for day trips, and Wednesday overnight and backpack hikes. We welcome non-members to night for overnight weekend trips. Early registration is helpful. participate in all our activities. Our hikes frequently include 2. Trips are seldom cancelled, even for inclement weather. If family groups of all ages. Non-members take responsibility for you must cancel, call the leader before he or she leaves for their individual safety and welfare on MCM excursions. the starting point. Members and guests who cancel after trip A “guest fee” of $2.00 is charged non-members. Club mem- arrangements have been made are billed for any food or other bers, through their dues, underwrite the expense of arranging expenses incurred. this schedule. Guests share these obligations through the medium 3. Arrive early; the time schedule is for departure – NOT of the guest fee. assembly. From its beginning, the MCM has recognized that mountain 4. -

Maryland's First State Park

PATAPSCO MARYLAND’S FIRST STATE PARK 1907 “The best time to plant a tree was twenty years ago and the second best time is today!” Fred W. Besley, Maryland’s First State Forester FORESTRY SERVICE NEEDED Long before the Forest Reserve was started, people took their leisure along the Patapsco River. From the valley’s mill towns and from A critical lumber shortage in the late 1800s called for reforestation Baltimore’s summer heat they came by horse and buggy and trolley efforts nationwide. car. They came seeking the refreshment of cool forest glens and unspoiled places to fish, hike, picnic and to ride horseback along the In 1906, John and Robert Garrett of Baltimore offered to the State of Falls of the Patapsco. It must have resembled a Grandma Moses Maryland 1,900 cut-over acres of land in Garrett County if the state painting with picturesque mills, villages and old-time steam would start a forestry service to demonstrate forest management locomotives pulling trains over a trace cut by Native American techniques. hunters. The following year, 1907, a prominent Catonsville farmer, John As early as 1910, the State Board of Forestry recognized both the Glenn, followed the Garrett example by donating 43 acres of his demand for recreation and the value of demonstrating the Hilton Estate (now the Patapsco State Park’s Hilton Area) to start the reforestation efforts to park visitors. Newspaper articles and posters Patapsco State Forest Reserve. One of the goals of this reserve was to invited the public to use and enjoy “Patapsco State Park.” While new slow the soil erosion from the slopes of the sparsely forested valley. -

Annual Report

Patapsco Heritage Greenway Board of Directors Steve Wachs President 2020 ANNUAL REPORT Victoria Goodman Vice President- Arts & Culture Challenges Bring Opportunities and Growth Sylvia Ramsey Vice President- Recreation The year 2020 certainly turned out differently than we all expected! Although challenging, Mark Southerland we have stayed on course with our mission and made significant progress toward opening Vice President-Environment even greater opportunities within the valley. Of key significance is the expansion of our Kathy Younkin Vice President-Heritage heritage area. Cathy Hudson Treasurer With MHAA’s approval of our boundary expansion in July the heritage area now includes Ken Boone most of Baltimore and Howard Counties’ Patapsco River watershed. This new boundary Secretary enables us to monitor and remediate additional, critical feeder streams and engage more Brooke Abercombie stream-watchers. It also brings new stories to share about the valley including forgotten Rudy Drayton granite quarries, immigrant experiences, and additional historical sites. It allows us to widen Chris Gallant our recreational trail network to include popular destination spots like Guinness Open Gate Ray Haislip John Heinrichs Brewery and to engage additional diverse cultural communities who share a love of the Gabriele Hourticolon Patapsco Valley. In the coming year our goal will be to explore ways that meld these varied Pam Johnson sites and stories into an enhanced experience for residents and visitors alike. Amanda Lauer Pete Lins Organizationally, since becoming President, I have created Board committees that coincide Marsha McLaughlin with key focus areas within our Management Plan– Heritage, Environment, Recreation, and David Nitkin Arts & Culture--each chaired by a vice-president.