Lessons from the Church of Silence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nineteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Monday, August

Saint John Gualbert Cathedral PO Box 807 Johnstown PA 15907-0807 539-2611 Stay awake and be ready! 536-0117 For you do not know on what day your Lord will come. Cemetery Office 536-0117 Fax 535-6771 Sunday, August 11, - Nineteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Readings: Wisdom 18:6-9/ Hebrews 11:1-2, 8-19 or 11:1-2, 8-12/ Luke 12:32-48 or 12:35-40 [email protected] 8:00 am: For the Intentions of the People of the Parish 11:00 am: Clarence Michael O’Shea (Great Granddaughter Dianne O’Shea) Bishop 5:00 pm: John Concannon (Kevin Klug) Most Rev Mark L Bartchak, DD Monday, August 12, - Weekday, Saint Jane Frances de Chantal, Religious Rector & Pastor Readings: Deuteronomy 10:12-22/ Matthew 17:22-27 Very Rev James F Crookston 7:00 am: Saint Anne Society 12:05 pm: Sophie Wegrzyn, Birthday Remembrance (Son, John) Parochial Vicar Father Clarence S Bridges Tuesday, August 13, - Weekday, Saints Pontian, Pope, & Hippolytus, Priest, Martyrs Readings: Deuteronomy 31:1-8/ Matthew 18:1-5, 10, 12-14 In Residence 7:00 am: Living & Deceased Members of 1st Catholic Slovac Ladies Father Sean K Code 12:05 pm: Bishop Joseph Adamec (Deacon John Concannon, Monica & Angela Kendera) SUNDAY LITURGY Wednesday, Saint Maximilian Kolbe, Priest & Martyr Saturday Evening Readings: Deuteronomy 34:1-12/ Matthew 18:15-20 5:00 pm Vigil Readings: 1 Chronicles 15:3-4, 15-16; 16:1-2/ 1 Corinthians 15:54b-57/ Luke 11:27-28 Sundays 7:00 am: Carole Vogel (Helen Muha) 8:00 am 12:05 pm: Anna Mae Cicon (Daughter, Melanie) 11:00 am 6:00 pm: Sara (Connors) O’Shea (Great Granddaughter, Dianne O’Shea 5:00 pm Thursday, August 15, - The Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary Readings: Revelation 11:19a; 12:1-6a, 10ab/ Corinthians 15:20-27/ Luke 1:39-50 7:00 am: Robert F. -

Angels Bible

ANGELS All About the Angels by Fr. Paul O’Sullivan, O.P. (E.D.M.) Angels and Devils by Joan Carroll Cruz Beyond Space, A Book About the Angels by Fr. Pascal P. Parente Opus Sanctorum Angelorum by Fr. Robert J. Fox St. Michael and the Angels by TAN books The Angels translated by Rev. Bede Dahmus What You Should Know About Angels by Charlene Altemose, MSC BIBLE A Catholic Guide to the Bible by Fr. Oscar Lukefahr A Catechism for Adults by William J. Cogan A Treasury of Bible Pictures edited by Masom & Alexander A New Catholic Commentary on Holy Scripture edited by Fuller, Johnston & Kearns American Catholic Biblical Scholarship by Gerald P. Fogorty, S.J. Background to the Bible by Richard T.A. Murphy Bible Dictionary by James P. Boyd Christ in the Psalms by Patrick Henry Reardon Collegeville Bible Commentary Exodus by John F. Craghan Leviticus by Wayne A. Turner Numbers by Helen Kenik Mainelli Deuteronomy by Leslie J. Hoppe, OFM Joshua, Judges by John A. Grindel, CM First Samuel, Second Samuel by Paula T. Bowes First Kings, Second Kings by Alice L. Laffey, RSM First Chronicles, Second Chronicles by Alice L. Laffey, RSM Ezra, Nehemiah by Rita J. Burns First Maccabees, Second Maccabees by Alphonsel P. Spilley, CPPS Holy Bible, St. Joseph Textbook Edition Isaiah by John J. Collins Introduction to Wisdom, Literature, Proverbs by Laurance E. Bradle Job by Michael D. Guinan, OFM Psalms 1-72 by Richard J. Clifford, SJ Psalms 73-150 by Richard J. Clifford, SJ Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther by James A. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS May 8, 1980 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

10672 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS May 8, 1980 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS NATIONAL SECURITY LEAKS potentiaf sources of intelligence infor Some of the stories say this informa mation abroad are reluctant to deal tion is coming out after all of the with our intelligence services for fear people involved have fled to safety. HON. LES ASPIN that their ties Will be exposed on the Maybe and maybe not. But if we are OF WISCONSIN front pages of American newspapers, worried about the cooperatic1n of for IN THE -HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES either because of leaks from Congress eigners, leaks like these would make Thursday, May 8, ,1980 or because sensitive material has been them extremely nervous about cooper leveraged out of the administration by ation. How can the leaker or leakers e Mr. ASPIN. Mr. Speaker, it is time FOIA. know everyone is safe? that we in Congress complain -}ust as We are also being told that, because Mr. Speaker, if foreigners are reluc loudly as those in the administration foreigners are fearful that secrets will tant to cooperate with us, it is the about national security leaks. be leaked, the intelligence agencies fault of our own agencies. Administrations, be they Republican must have the power to blue pencil They should know that the fault is or Democrat, have a predilection for manuscripts written by present and not. in Congress or in the FOIA but in pointing at Congress and bewailing former intelligence officers to make themselves. Recall that despite weeks the fact that the legislative branch sure they don't reveal anything sensi of forewarning, our people rushed out can't keep a secret. -

Kornberg on Godman, 'Hitler and the Vatican: Inside the Secret Archives That Reveal the New Story of the Nazis and the Church'

H-German Kornberg on Godman, 'Hitler and the Vatican: Inside the Secret Archives that Reveal the New Story of the Nazis and the Church' Review published on Saturday, October 1, 2005 Peter Godman. Hitler and the Vatican: Inside the Secret Archives that Reveal the New Story of the Nazis and the Church. New York: Free Press, 2004. xvi + 282 pp. $27.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-7432-4597-5. Reviewed by Jacques Kornberg (Department of History, University of Toronto)Published on H- German (October, 2005) The Vatican and National Socialism: Between Criticism and Conciliation Peter Godman of the University of Rome, a scholar who has studied the Catholic Church, was one of the first people granted permission to mine the recently opened archives of the Supreme Congregation of the Holy Office for the pontificate of Pius XI (1922-39). In keeping with the times, the Holy Office currently bears the less forbidding name of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith; it was once known as the Universal Inquisition. Headed by bishops and cardinals, the Congregation pronounces on doctrine in matters of faith and morals. Godman contrasts his own "behind the scenes" view based on a close reading of the Holy Office documents, with the "hot air of speculation" hanging over the works of John Cornwell and Daniel Goldhagen. There is some truth to his claim, but he sets expectations too high when he professes to open a window into "the thoughts and motives" of those who made policy (p. xv). All we have of Pius XI and his Secretary of State, Cardinal Pacelli, are office memos, public statements, protocols of meetings, reports of papal audiences, and letters to bishops; we will always have to stake out some educated guesses about their thoughts and motives. -

Distributism Debate

The Distributism Debate The Distributism Debate Dane J. Weber Donald P. Goodman III Eds. GP Goretti Publications Dozenal numeration is a system of thinking of numbers in twelves, rather than tens. Twelve is much more versatile, having four even divisors—2, 3, 4, and 6—as opposed to only two for ten. This means that such hatefulness as “0.333. ” for 1/3 and “0.1666. ” for 1/6 are things of the past, replaced by easy “0;4” (four twelfths) and “0;2” (two twelfths). In dozenal, counting goes “one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten, elv, dozen; dozen one, dozen two, dozen three, dozen four, dozen five, dozen six, dozen seven, dozen eight, dozen nine, dozen ten, dozen elv, two dozen, two dozen one. ” It’s written as such: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, X, E, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 1X, 1E, 20, 21... Dozenal counting is at once much more efficient and much easier than decimal counting, and takes only a little bit of time to get used to. Further information can be had from the dozenal societies (http:// www.dozenal.org), as well as in many other places on the Internet. © 2006 (11E2) Dane J. Weber and Donald P. Goodman III, Version 3.0. All rights reserved. This document may be copied and distributed freely, provided that it is done in its entirety, including this copyright page, and is not modified in any way. Goretti Publications http://gorpub.freeshell.org [email protected] No copyright on this work is intended to in any way derogate from the copyright holders of any individual part of this work. -

![I Alcoholism ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6936/i-alcoholism-676936.webp)

I Alcoholism ]

The Week in Religion Catholic U. Senior Heads National Religious Club ! By the Associated Press [from Merchantville, N. J., vice in PHILADELPHIA, Mar. 24.—F. president; Michael Graney, Brook- Czech Red Government Drives a Wedge Catholic Church Girard Mueller of Baltimore, a lyn, Manhattan student, secre- and Frank By Religious News Service jcathedral chapters and put “pa- have acted against the ecclesiasti- nouncements have become a senior at Catholic University, tary. Shelvin, Belaire, in their jLong Island, ty. Y„ also a Manhat- Current tend to triotic” priests place. authorities. standard feature. Washington, was elected president developments cal tan student, treasurer. last week to these to from un- of Cigma Beta Kappa, National confirm fears expressed by Vati- Referring The sacred consistorial According reports — congre-; Catholic Action can circles a year ago that the state appointments, Vice Premier derground sources in Czechoslo- fraternity, during gation in Rome has excommuni- the third annual convention I "Mass dismissals” have stirred Czechoslovak Communist govern- Zdenek Fierlinger, who heads the vakia, government officials are dis- today cated all those “morally and phys- at La Salle workers’ ire in Indonesia but em- ment was planning to set up a state office for church affairs, turbed over the growing practice College. I ically” involved in the banishment Other officers named were: say are strictly sea- national Catholic Church separ- hailed them as marking “the of Catholics to make long trips on ployers they of Archbishop Beran. It also im- Glenn ated from Rome. democratization of the Sundays to the nearest church Robertson, La Salle (Student sonal. ;gradual posed the same penalty on clerics Catholic Church and its where propaganda-free services In March. -

Father Włodzimierz Ledóchowski (1866–1942): Driving Force Behind Papal Anti-Communism During the Interwar Period

journal of jesuit studies 5 (2018) 54-70 brill.com/jjs Father Włodzimierz Ledóchowski (1866–1942): Driving Force behind Papal Anti-Communism during the Interwar Period Philippe Chenaux Pontifical Lateran University [email protected] Abstract Włodzimierz Ledóchowski, superior general of the Society of Jesus, wielded great in- fluence in the battle against Communism. His belief that there was a link of some degree between Jews and Communism, his work to establish a secretariat in Rome to counter atheistic Communism, and his influence in the development of the papal encyclical, Divini redemptoris, are explored in this article. Convinced that the Russian Revolution was a satanic force out to eradicate Christian society, Ledóchowski made it his life’s work to expose the lies and threats of Bolshevism, culminating in his pen- ultimate Congregation (in 1938) where the superior general discussed techniques that could be used to combat the spread of Communism. Keywords Communism – Bolshevism – anti-Semitism – Jesuit superior general – Włodzimierz Ledóchowski – Divini redemptoris Father Włodzimierz Ledóchowski (1866–1942), elected twenty-sixth supe- rior general of the Jesuits on February 11, 1915, was undoubtedly a key, and controversial, figure in the modern history of the Society of Jesus.1 He was 1 As no true biography exists, please refer to Giacomo Martina’s biographical notes: “Ledóchowski (Wlodimir), général de la Compagnie de Jésus (1866–1942),” in Dictionnaire d’histoire et de géographie ecclésiastiques, ed. Roger Aubert and Luc Courtois, Fascicule 180: Le Couëdic-Le Hunsec (Paris: Letouzey & Ané, 2010), 54–62, and biographical information by © chenaux, 2018 | doi 10.1163/22141332-00501004 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the prevailing CC-BY-NC license at the time of publication. -

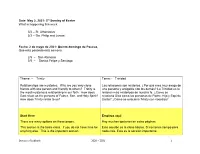

May 2, 2021: 5Th Sunday of Easter What Is Happening This Week

Date: May 2, 2021: 5th Sunday of Easter What is happening this week 5/2 – St. Athanasius 5/3 – Sts. Philip and James Fecha: 2 de mayo de 2021: Quinto domingo de Pascua, Que esta pasando esta semana 2/5 – San Atanasio 3/5 – Santos Felipe y Santiago Theme: – Trinity Tema: - Trinidad Relationships are mysteries. Why are you very close Las relaciones son misterios. ¿Por qué eres muy amigo de friends with one person and friendly to others? Trinity is una persona y amigable con los demás? La Trinidad es la the most mysterious relationship in our faith. How does relación más misteriosa de nuestra fe. ¿Cómo se God relate as the persons of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit? relaciona Dios como las personas de Padre, Hijo y Espíritu How does Trinity relate to us? Santo? ¿Cómo se relaciona Trinity con nosotros? Start Here Empieza aqui There are many options on these pages. Hay muchas opciones en estas páginas. This section is the basic class. If you do not have time for Esta sección es la clase básica. Si no tienes tiempo para anything else. This is the important section. nada más. Esta es la sección importante. Diocese of Lubbock 2020 – 2021 1 What To Do What To Do 1. Preparation 1. Preparación a. Clear away distractions a. Elimina las distracciones b. Set the "mood" b. Establecer el estado de ánimo" i. Find your gathering space i. Encuentra tu espacio de reunión ii. Bring out a Cross, Crucifix, Bible, Holy ii. Saque una cruz, un crucifijo, una Biblia, una Picture, and/ or a statue imagen sagrada y / o una estatua. -

19630628.Pdf

THE CRITERION, JUNE ?8, I963 PAGE THRES - SupremeCourt decision Help t'or aging - Cotugo Ar home ::31:r""::-T,.ll:..^l: l.l:: ll^".111",.^11.1groups ha\,e brought:.:l'J...111"..,:.'.'li*i?ll' aboul Ihtr "thr.otrgh improvement conlol'- cnces ancl an cxchangc ol in{or'- " nration. Abroad I LONDON-]'he luling l,abor' I'arty in Australia rvill not butlgc ft'ortt its opposition to g.rveln- nrent aid to Catholic antl othcr' privatc schools, thc ptlty's lcatlcr. has rleclaletl hcrc. Arthur' (.lal- well insisted that sialc glants lo non.public schools are not. pos- sible undel the plesent. Cornrnon. wcalth eonstitution. Cnln'el[. rvho is a Catholic, said thal. clenton- stlations by Catholic pa|cnts agaittst the govet'nmcnt's policl'. Office of Education here, de- f \ rvhich inclrrtlctl ntass tt'attsfcls ol scribed lhe school siluation ar , I "dismal." stttdents fronr Catholic to public The strike involves I I "no schools, rvoukl have lusting 37,500 leachers and rffecls | ^ - ^ | c[[cct''intlrosc[rooldisettssit.rtrs'morelhanami||ionpupi|s.i}fl-l o\%u,j*tAMOUNT TO BETREPAIoBE REPAIO ovERlOVER I I sAN'ro DotttN(;o. Dotttitticurt ; l-1 I YOU Fro |lr,lrrrlrlit,-|l|irslltrt.a..;i:i;l';;i#|eohi-ow|ro-o".|romoo,|z|mos.|!BORROW 36m 30 moo. 2l mos. li.:;',lllill:,:i':lt:i';',llli.'li:|.llll|isll!llJr/ohffil$ 600 29.00 000 40,00 48.3i1 lilll;\,:]l:'T;ll.'i]l.ll,.:lli:1"iil,jliitT'rUlH"fA1500 $51.66 60.00 72.50 rclij.tion u,ilI cvcntuaIlv disappenr'. -

The Catholic Church in the Czech Lands During the Nazi

STUDIA HUMANITATIS JOURNAL, 2021, 1 (1), pp. 192-208 ISSN: 2792-3967 DOI: https://doi.org/10.53701/shj.v1i1.22 Artículo / Article THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE CZECH LANDS DURING THE NAZI OCCUPATION IN 1939–1945 AND AFTER1 LA IGLESIA CATÓLICA EN LOS TERRITORIOS CHECOS DURANTE LA OCUPACIÓN NAZI ENTRE LOS AÑOS 1939–1945 Y DESPUÉS Marek Smid Charles University, Czech Republic ORCID: 0000-0001-8613-8673 [email protected] | Abstract | This study addresses the religious persecution in the Czech lands (Bohemia, Moravia and Czech Silesia) during World War II, when these territories were part of the Bohemian and Moravian Protectorate being occupied by Nazi Germany. Its aim is to demonstrate how the Catholic Church, its hierarchy and its priests acted as relevant patriots who did not hesitate to stand up to the occupying forces and express their rejection of their procedures. Both the domestic Catholic camp and the ties abroad towards the Holy See and its representation will be analysed. There will also be presented the personalities of priests, who became the victims of the Nazi rampage in the Czech lands at the end of the study. The basic method consists of a descriptive analysis that takes into account the comparative approach of the spiritual life before and after the occupation. Furthermore, the analytical-synthetic method will be used, combined with the subsequent interpretation of the findings. An additional method, not always easy to apply, is hermeneutics, i.e., the interpretation of socio-historical phenomena in an effort to reveal the uniqueness of the analysed texts and sources and emphasize their singularity in the cultural and spiritual development of Czech Church history in the first half of the 20th century. -

Vatican Secret Diplomacy This Page Intentionally Left Blank Charles R

vatican secret diplomacy This page intentionally left blank charles r. gallagher, s.j. Vatican Secret Diplomacy joseph p. hurley and pope pius xii yale university press new haven & london Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Copyright © 2008 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Scala and Scala Sans by Duke & Company, Devon, Pennsylvania. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gallagher, Charles R., 1965– Vatican secret diplomacy : Joseph P. Hurley and Pope Pius XII / Charles R. Gallagher. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-12134-6 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Hurley, Joseph P. 2. Pius XII, Pope, 1876–1958. 3. World War, 1939–1945— Religious aspects—Catholic Church. 4. Catholic Church—Foreign relations. I. Title. BX4705.H873G35 2008 282.092—dc22 [B] 2007043743 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Com- mittee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To my father and in loving memory of my mother This page intentionally left blank contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 1 A Priest in the Family 8 2 Diplomatic Observer: India and Japan, 1927–1934 29 3 Silencing Charlie: The Rev. -

Croatia 2016 International Religious Freedom Report

CROATIA 2016 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution provides for freedom of religious thought and expression and prohibits incitement of religious hatred. Registered religious groups are equal under the law and free to publicly conduct religious services and open and manage schools and charitable organizations with assistance from the state. The government has four written agreements with the Roman Catholic Church that provide state financial support and other benefits, while the law accords other registered religious groups the same rights and protections. In April, government ministers attended the annual commemoration at the site of the World War II (WWII)-era Jasenovac death camp. Jewish and Serb (largely Orthodox) leaders boycotted the event and held their own commemorations, saying the government had downplayed the abuses of the WWII-era Nazi-aligned Ustasha regime. A talk show host warned people to stay away from an area in Zagreb where a Serbian Orthodox Church (SOC) was located, saying “Chetnik vicars” would murder innocent bystanders. Spectators at a soccer match against Israel chanted pro-fascist slogans used under the WWII-era, Nazi-aligned Ustasha regime while the prime minister and Israeli ambassador were in attendance. Director Jakov Sedlar screened the Jasenovac – The Truth documentary which questioned the number of killings at the camp, inciting praise and criticism. SOC representatives expressed concern over a perceived increase in societal intolerance. The SOC estimated 20 incidents of vandalism against SOC property. The U.S. embassy continued to encourage the government to restitute property seized during and after WWII, especially from the Jewish community, and to adopt a claims process for victims.