Le Mans for Dummies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redwood Region Newsletter Newsletter Date: January 10, 2008 9:18:58 AM PST To: [email protected] Reply-To: William [email protected]

From: william walters <[email protected]> Subject: Redwood Region Newsletter Newsletter Date: January 10, 2008 9:18:58 AM PST To: [email protected] Reply-To: [email protected] P O R S C H E der Reisenbaum Redwood Region Newsletter Porsche Club of America Del Norte, Humboldt, Lake, Marin, Mendocino, Napa and Sonoma January 2008 Issue II Volume I ; electronic newsletter Bill Walters, editor Kurt Fischer, assistant editor See us on the web at: http://red.pca.org//index.htm President's Message Kurt Fischer It's New Year's Eve and I'm thinking of the 2008 calendar and all the events that will be forthcoming...what an action packed year we have in store! Bob Hall's great breakfast runs, our 9 Autocrosses; more of Greg Chamber's "Artisan" wine tours, car corrals for the Wine Country Classics and Grand AM/IRL races at Infineon Raceway, our overnight tours to Eureka and Mendocino, PCA Escape #4 in Albuquerque, NM and the list goes on! Look for several "special" surprise events that are in the works as well. More details will follow in the upcoming months! Again...I want to thank the members of the Redwood Region for their participation in the events of 2007. Our members are the heart and soul of this group and we try to accommodate all of your wishes for events! If you would like to suggest a new event, please let me know! I'd like to welcome Bret Boutet as our new Membership Chairman. He spent a day with Dave and LaVonne Benson learning all the nuances of this very important job and will be a welcome addition to our Board of Directors. -

Porsche in Le Mans

Press Information Meet the Heroes of Le Mans Mission 2014. Our Return. Porsche at Le Mans Meet the Heroes of Le Mans • Porsche and the 24 Hours of Le Mans 1 Porsche and the 24 Hours of Le Mans Porsche in the starting line-up for 63 years The 24 Hours of Le Mans is the most famous endurance race in the world. The post-war story of the 24 Heures du Mans begins in the year 1949. And already in 1951 – the pro - duction of the first sports cars in Stuttgart-Zuffenhausen commenced in March the previous year – a small delegation from Porsche KG tackles the high-speed circuit 200 kilometres west of Paris in the Sarthe department. Class victory right at the outset for the 356 SL Aluminium Coupé marks the beginning of one of the most illustrious legends in motor racing: Porsche and Le Mans. Race cars from Porsche have contested Le Mans every year since 1951. The reward for this incredible stamina (Porsche is the only marque to have competed for 63 years without a break) is a raft of records, including 16 overall wins and 102 class victories to 2013. The sporting competition and success at the top echelon of racing in one of the world’s most famous arenas is as much a part of Porsche as the number combination 911. After a number of class wins in the early fifties with the 550, the first time on the podium in the overall classification came in 1958 with the 718 RSK clinching third place. -

Download The

ROLEX 24 AT DAYTONA - 2016 NEW MACHINES Ford joins BMW and Ferrari in debuting new GTLM machines in 2016 READY TO RUMBLE AT THE ROLEX 2016 GTLM BATTLE FIRST to FIRST Ford, Ferrari, BMW Debut New Cars 2 If the first major race of the New Year asks, “what’s “When you have a brand new car you always find some new?” The answer is, “nearly everything.” things that are not ideal and then you work to improve The Rolex 24 At Daytona is the first event for the new those things or to adjust to them,” said Luhr, whose veteran IMSA WeatherTech SportsCar Championship and opens the BMW Team RLL finished second by a mere 0.48 seconds here stunning $400 million Daytona Rising Stadium. Icing the in 2015. new season cake is the spectacular array of new cars. While the popular Risi Competizione team awaited The highly anticipated debut of the Chip Ganassi Racing delivery of its new Ferrari 488 GTE, the team joined with (CGR) Ford EcoBoost GTs adds yet another top manufacturer longtime Ferrari stalwart AF Corse at the recent Roar Before and a pair of stunning cars to the powerful GTLM class. the 24 test with GTLM newcomers Scuderia Corsa and SMP Since Ford announced its return to competition at Racing in a thorough testing regimen of the new car. Le Mans last June, the Ford CGR team has been on an While the pace, traffic, and reliability challenges in the aggressive testing and development path in preparation for frantic Rolex 24 At Daytona are daunting, an even bigger its competition debut here. -

RSR Final Desc.Pages

! The 1973 Sebring 12 Hours Winning 1973 Porsche 911 2.8 RSR Ex. Hurley Haywood, Peter Gregg Chassis No. : 911.360.0705 • Without a doubt one of the most significant Porsche 911 of all time. • Run by the legendary Brumos Team and driven to outright victory in the 1973 Sebring 12 Hours by Peter Gregg, Hurley Haywood and David Helmick. • Retained and preserved in the long term collection of well known Porsche collector Dr. Bill Jackson. • A once in a lifetime opportunity to own the car that claimed one the three most important outright wins for the Porsche 911 of all time. Since the company was founded in 1931 by Dr. Ferdinand Porsche, Porsche has been responsible for some of the most iconic cars of all time. Perhaps the most important of these is the Porsche 911, a design concept which has endured for more than half a century and is still successful both commercially on the road and in competition on the race track. Designed by Ferdinand Porsche’s son Ferry, the 911 was a replacement for Porsche’s 356 model and made it’s debut at the 1963 Frankfurt Motor Show. It was originally badged as the 901 and had a 128hp, 1991cc flat 6 engine in boxer configuration, which was air cooled and rear mounted and mated to a five speed manual transmission. After a mere 82 cars had been produced, a legal challenge from Peugeot concerning the car name, led Porsche to change the name to 911. T. + 44 (0)1285 831 488 E. [email protected] www.williamianson.com ! The Porsche factory did not decide to start racing the 911 immediately choosing to focus its attention on the purpose designed 906, 908 and 910 prototypes. -

The Porsche Collection Phillip Island Classic PORSCHES GREATEST HITS PLAY AGAIN by Michael Browning

The Formula 1 Porsche displayed an interesting disc brake design and pioneering cooling fan placed horizontally above its air-cooled boxer engine. Dan Gurney won the 1962 GP of France and the Solitude Race. Thereafter the firm withdrew from Grand Prix racing. The Porsche Collection Phillip Island Classic PORSCHES GREATEST HITS PLAY AGAIN By Michael Browning Rouen, France July 8th 1962: It might have been a German car with an American driver, but the big French crowd But that was not the end of Porsche’s 1969 was on its feet applauding as the sleek race glory, for by the end of the year the silver Porsche with Dan Gurney driving 908 had brought the marque its first World took the chequered flag, giving the famous Championship of Makes, with notable wins sports car maker’s new naturally-aspirated at Brands Hatch, the Nurburgring and eight cylinder 1.5 litre F1 car its first Grand Watkins Glen. Prix win in only its fourth start. The Type 550 Spyder, first shown to the public in 1953 with a flat, tubular frame and four-cylinder, four- camshaft engine, opened the era of thoroughbred sports cars at Porsche. In the hands of enthusiastic factory and private sports car drivers and with ongoing development, the 550 Spyder continued to offer competitive advantage until 1957. With this vehicle Hans Hermann won the 1500 cc category of the 3388 km-long Race “Carrera Panamericana” in Mexico 1954. And it was hardly a hollow victory, with The following year, Porsche did it all again, the Porsche a lap clear of such luminaries this time finishing 1st, 2nd, 4th and 5th in as Tony Maggs’ and Jim Clark’s Lotuses, the Targa Florio with its evolutionary 908/03 Graham Hill’s BRM. -

Le Mans (Not Just) for Dummies the Club Arnage Guide

Le Mans (not just) for Dummies The Club Arnage Guide to the 24 hours of Le Mans 2011 "I couldn't sleep very well last night. Some noisy buggers going around in automobiles kept me awake." Ken Miles, 1918 - 1966 Copyright The entire contents of this publication and, in particular of all photographs, maps and articles contained therein, are protected by the laws in force relating to intellectual property. All rights which have not been expressly granted remain the property of Club Arnage. The reproduction, depiction, publication, distr bution or copying of all or any part of this publication, or the modification of all or any part of it, in any form whatsoever is strictly forbidden without the prior written consent of Club Arnage (CA). Club Arnage (CA) hereby grants you the right to read and to download and to print copies of this document or part of it solely for your own personal use. Disclaimer Although care has been taken in preparing the information supplied in this publication, the authors do not and cannot guarantee the accuracy of it. The authors cannot be held responsible for any errors or omissions and accept no liability whatsoever for any loss or damage howsoever arising. All images and logos used are the property of Club Arnage (CA) or CA forum members or are believed to be in the public domain. This guide is not an official publication, it is not authorized, approved or endorsed by the race-organizer: Automobile Club de L’Ouest (A.C.O.) Mentions légales Le contenu de ce document et notamment les photos, plans, et descriptif, sont protégés par les lois en vigueur sur la propriété intellectuelle. -

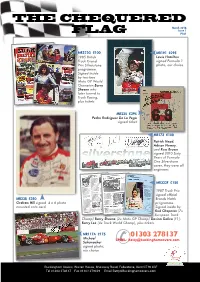

The Chequered Flag

THE CHEQUERED March 2016 Issue 1 FLAG F101 MR322G £100 MR191 £295 1985 British Lewis Hamilton Truck Grand signed Formula 1 Prix Silverstone photo, our choice programme. Signed inside by two-time Moto GP World Champion Barry Sheene who later turned to Truck Racing, plus tickets MR225 £295 Pedro Rodriguez De La Vega signed ticket MR273 £100 Patrick Head, Adrian Newey, and Ross Brawn signed 2010 Sixty Years of Formula One Silverstone cover, they were all engineers MR322F £150 1987 Truck Prix signed official MR238 £350 Brands Hatch Graham Hill signed 4 x 6 photo programme. mounted onto card Signed inside by Rod Chapman (7x European Truck Champ) Barry Sheene (2x Moto GP Champ) Davina Galica (F1), Barry Lee (4x Truck World Champ), plus tickets MR117A £175 01303 278137 Michael EMAIL: [email protected] Schumacher signed photo, our choice Buckingham Covers, Warren House, Shearway Road, Folkestone, Kent CT19 4BF 1 Tel 01303 278137 Fax 01303 279429 Email [email protected] SIGNED SILVERSTONE 2010 - 60 YEARS OF F1 Occassionally going round fairs you would find an odd Silverstone Motor Racing cover with a great signature on, but never more than one or two and always hard to find. They were only ever on sale at the circuit, and were sold to raise funds for things going on in Silverstone Village. Being sold on the circuit gave them access to some very hard to find signatures, as you can see from this initial selection. MR261 £30 MR262 £25 MR77C £45 Father and son drivers Sir Jackie Jody Scheckter, South African Damon Hill, British Racing Driver, and Paul Stewart. -

Amelia Island Concours D'elegance

One more for the bucket list: Amelia Island Concours d’Elegance It was Sunday at 10:30 AM, and I had missed my chance to enter the Amelia Island Concours d’Elegance before the line into the show field grew to what looked like thousands of people. This was just the tip of the iceberg, as thousands more already had gained entrance. It was my first Amelia Island Concours, but no, I don’t regret being late to the show. Early that morning, I had walked down to the parking garage on a tip that there would be a couple cars worth photographing on their way out to the field: the Porsche Museum’s 909 Bergspyder and hallowed flat-16-powered 917 PA. In the garage, it was easy to admire their curves, their history, and their cylinder count — 24 between the two of them. Behind the chain-link fence guarding the RM Auction cars, the two Porsches sat. Not another car back there could sway my attention. At 8 AM, they were tugged from their slumber by a golf cart and pulled to the show field. A few Porsches parked on my side of the fence were able to peel me away from the museum-kept racecars for a few moments. The first was the No. 67 BF Goodrich 1985 962, which was driven by Amelia Island honoree Jochen Mass at the 1985 24 Hours of Daytona, where he placed third overall. PCA member Bob Russo, the man who restored it, was standing by its side and spoke to me about the build and how it was finished just the week before. -

Excellence Monterey 98

The Magazine NOVEMBER I 998 ll llllilillllililllllllll llrfiril $4.95 (Canada $5.95) have a further distinction, as Porsche hardly looked like the progenitor of all AG chose to celebrate its 50th those snorting beasts that surrounded anniversary at Laguna Seca during the it in Laguna's pit lane, Monterey Historics weekend. The f irst Porsche built at GmUnd The most notable aspect of the after the war 356 00 1, was supposed weekend at the track was the opportu- to lap the track this year with Dr. Wolfgang Porsche at the controls This - annua i.': seminal car last visited the U.S. in includes.'='.' 1982, when it took pride of place at the Porsche Parade Concours at '.2 Concou rs Reno. Unfortunately, it was damaged ,,. happen .- upon arrival in the U.S. and was miles of : .- eaa- = rnable to be repaired in time for the Thrci'. n ., _-= -' - =.3-. E,.,en the 356 specialists at tion t g' . ., s.'==. J .::,'l--'e.'. .p the,r hands in dis- enthus as: a :'-.. l - a.. .. -=' asl.ed to perform a quich worid and is eas '::t-, . So the remains of 356 001 are weekend has oeco--e aa./ - Germany now, waiting for mier vintage car eve 'e ca' Dr Wolfgang Porsche did his Monterey weekend, how aos aboard a 1951 twin-windscreen 72 EXCELLENCE November1998 --l a : -="' -Z' :.' =e", Porsche and Vasek Polak are roadster first raced bY Sauter. .^--^=e''=:'-'Z'. -^ :':')=) gone now, but the excellence theY Those who attended the Historics J= -; - =,.-- Z '::'a"'-3 O' exhrbited lingers on This Year, the 16 years ago may recall that 001 did T-='=:'=Z'.-':: pinned their Dc'sc-: s ':::3s: 'ace car' the N,4obY Iegions of drivers who f parade laPs of the track at our full caieers on Porsche returned again to Seca on August 21 1982 D c<-s:y'e Kreme r K-3 evo. -

August 2012 CIRPCA President’S Message

The Official Publication of the Central Indiana Region, Porsche Club of America 2012 / #8 CIRCIRCULARCULAR IN THIS ISSUE: PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE EDITORS MESSAGE BRICKYARD GRAND PRIX STORY AND PICS! Tom Wood Porsche 317-848-5550 877-859-5550 CIRcular 2 The Official Publication of the Central Indiana Region, Porsche Club of America Central Indiana Region Please visit the CIR Web Site for the 2012 Board of Directors latest CIR News. It lists the latest Por- sche related wire news, member photos, President event photos, upcoming events links, the Rob Fike (317) - 244-1166 latest forum postings, site info and more [email protected] If you haven’t yet, join other members Vice-President and “LIKE” CIR on the home page OPEN [email protected] Visit the Calendar for the latest event in- Treasurer fo Simon Robinson Visit the Gallery for the latest event pho- [email protected] tos Secretary OPEN Visit the Member Car Photos for mem- [email protected] ber car photos. If yours isn’t there yet, Membership contact the CIR Webmaster. Bob Snider - (765) 282-7985 [email protected] CIRcular newsletters can be found at Activities OPEN The CIR FORUMS has many individual [email protected] forums from CIR info, to for sale, want- Past President ed, specific model info, general mainte- Don Shuck—(317) 374-8772 Members at Large nance and suggestions box discussion Randy Faunce - (317) 861-0755 areas Merritt Webb, CIRCULAR Editor - (260) 497-0856 [email protected] Got to Contact Us to contact any board David Weaver, Webmaster - (317) 769-5802 member [email protected] The CIR Driver Ed Links menu item lists CIRCULAR IS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE the upcoming DE event, DE FAQs, Put- CENTRAL INDIANA REGION, PORSCHE CLUB OF AMERICA. -

Works Porsche 962-006

www.porscheroadandrace.com Works Porsche 962-006 Published: 8th December 2017 By: Glen Smale Online version: https://www.porscheroadandrace.com/works-porsche-962-006/ Rothmans Porsche 962C (chassis #006) 1987 Le Mans 24 Hour winner photographed at Porsche Museum in Stuttgart, May 2017 The Porsche 956 and its successor the 962, are widely and justifiably regarded as the most successful sports racing prototypes of their era, and quite possibly ever. Over a period of some twelve years, this model racked up 232 international victories on every continent in the world. This included the World Sportscar Championship, IMSA, Japanese Sportscar Championship, DRM, Interserie, Supercup and Can-Am. No other car of its type was successful for more than one or two seasons at best, but the 956/962 reigned supreme for at www.porscheroadandrace.com least 6-8 years, and was successful at an international level for up to twelve years. This is the story of the works Porsche 962-006. Rothmans Porsche 962C (chassis #006) 1987 Le Mans 24 Hour winner photographed at Porsche Museum in Stuttgart, May 2017 If you speak to any of the Porsche engineers associated with the development of the 956 or the 962, you will be told that these two models are regarded within the racing department as one model. In an interview with Jürgen Barth in 2011, I asked him what the difference between the 956 and 962 meant to them in the race department, and he replied, “No difference, it was only the length of the chassis. For me it [the 956 and 962] is the same thing.” www.porscheroadandrace.com Rothmans Porsche 962C (chassis #006) 1987 Le Mans 24 Hour winner photographed at Porsche Museum in Stuttgart, May 2017 Only ten examples each of the 956 and 962 models were made and retained by the factory for use by the official works teams in period, with a further total of (approximately) 130 units being manufactured for the various privateer teams over a 12-year period. -

Vern Schuppan

Vern Schuppan Born in Australia, Vern Schuppan won the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1983 and was part of the Porsche works team until 1988. Full of hope and optimism, Vern Schuppan went to England in 1969 at the age of 26 to become a racing driver. In 1970, he visited the 1,000 kilometre race at Brands Hatch, where he admired the driving skills of Jo Siffert and Pedro Rodriguez in their Porsche 917. ‘Their performance in the rain was very impressive,’ noted Schuppan. ‘I wonder if I will ever drive a 917?’ In 1972, Schuppan joined John Wyer’s Gulf team, but he was already using the Mirage Ford at this point. It was not until 2012 that his great wish came true: as a 69-year-old racing veteran, Schuppan finally had the opportunity to drive a Porsche 917 at the Le Mans Classic. In the early years of his career, Schuppan competed in some Formula One races for smaller teams like BRM, Ensign, Embassy Hill and Surtees. In the United States, he came third in the Indianapolis 500 in 1981. In the same year, Porsche required him to race in Le Mans, where he took 12th place after some engine problems in the Porsche 936. Racing manager Peter Falk was looking for drivers ‘with brains’ for the new Group C and its fuel consumption regulations – men with a consistent and gentle style. Schuppan was one of those up for selection, and in 1982 he finished second at the side of Jochen Mass when the Porsche 956 made its debut at Le Mans.