Paraguay Country Handbook This Handbook Provides Basic Reference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Web Apr 06.Qxp

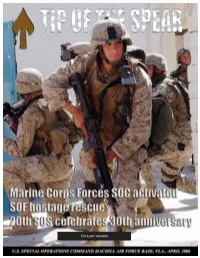

On-Line version TIP OF THE SPEAR Departments Global War On Terrorism Page 4 Marine Corps Forces Special Operations Command Page 18 Naval Special Warfare Command Page 21 Air Force Special Operations Command Page 24 U.S. Army Special Operations Command Page 28 Headquarters USSOCOM Page 30 Special Operations Forces History Page 34 Marine Corps Forces Special Operations Command historic activation Gen. Doug Brown, commander, U.S. Special Operations Command, passes the MARSOC flag to Brig. Gen. Dennis Hejlik, MARSOC commander, during a ceremony at Camp Lejune, N.C., Feb. 24. Photo by Tech. Sgt. Jim Moser. Tip of the Spear Gen. Doug Brown Capt. Joseph Coslett This is a U.S. Special Operations Command publication. Contents are Commander, USSOCOM Chief, Command Information not necessarily the official views of, or endorsed by, the U.S. Government, Department of Defense or USSOCOM. The content is CSM Thomas Smith Mike Bottoms edited, prepared and provided by the USSOCOM Public Affairs Office, Command Sergeant Major Editor 7701 Tampa Point Blvd., MacDill AFB, Fla., 33621, phone (813) 828- 2875, DSN 299-2875. E-mail the editor via unclassified network at Col. Samuel T. Taylor III Tech. Sgt. Jim Moser [email protected]. The editor of the Tip of the Spear reserves Public Affairs Officer Editor the right to edit all copy presented for publication. Front cover: Marines run out of cover during a short firefight in Ar Ramadi, Iraq. The foot patrol was attacked by a unknown sniper. Courtesy photo by Maurizio Gambarini, Deutsche Press Agentur. Tip of the Spear 2 Highlights Special Forces trained Iraqi counter terrorism unit hostage rescue mission a success, page 7 SF Soldier awarded Silver Star for heroic actions in Afghan battle, page 14 20th Special Operations Squadron celebrates 30th anniversary, page 24 Tip of the Spear 3 GLOBAL WAR ON TERRORISM Interview with Gen. -

The Role and Importance of the Military Diplomacy in Affirming

ESCOLA DE COMANDO E ESTADO-MAIOR DO EXÉRCITO ESCOLA MARECHAL CASTELLO BRANCO Cel Art PAULO CÉSAR BESSA NEVES JÚNIOR The Role and Importance of the Military Diplomacy in affirming Brazil as a Regional Protagonist in South America (O Papel e a importância da Diplomacia Militar na afirmação do Brasil como um Protagonista Regional na América do Sul) Rio de Janeiro 2019 Col Art PAULO CÉSAR BESSA NEVES JÚNIOR The Role and Importance of the Military Diplomacy in affirming Brazil as a Regional Protagonist in South America (O Papel e a importância da Diplomacia Militar na afirmação do Brasil como um Protagonista Regional na América do Sul) Course Completion Paper presented to the Army Command and General Staff College as a partial requirement to obtain the title of Expert in Military Sciences, with emphasis on Strategic Studies. Advisor: Cel Inf WAGNER ALVES DE OLIVEIRA Rio de Janeiro 2019 N518r Neves Junior, Paulo César Bessa The role and importance of the military diplomacy in affirming Brazil as a regional protagonist in Souht America. / Paulo César Bessa Neves Júnior . 一2019. 23 fl. : il ; 30 cm. Orientação: Wagner Alves de Oliveira Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso (Especialização em Ciências Militares)一Escola de Comando e Estado-Maior do Exército, Rio de Janeiro, 2019. Bibliografia: fl 22-23. 1. DIPLOMACIA MILITAR. 2. AMÉRICA DO SUL. 3. BASE INDUSTRIAL DE DEFESA I. Título. CDD 372.2 Col Art PAULO CÉSAR BESSA NEVES JÚNIOR The Role and Importance of the Military Diplomacy in affirming Brazil as a Regional Protagonist in Souht America (O Papel e a importância da Diplomacia Militar na afirmação do Brasil como um Protagonista Regional na América do Sul) Course Completion Paper presented to the Army Command and General Staff College as a partial requirement to obtain the title of Expert in Military Sciences, with emphasis on Strategic Studies. -

Paraguay's Archive of Terror: International Cooperation and Operation Condor Katie Zoglin

University of Miami Law School Institutional Repository University of Miami Inter-American Law Review 4-1-2001 Paraguay's Archive of Terror: International Cooperation and Operation Condor Katie Zoglin Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umialr Part of the Foreign Law Commons, and the Human Rights Law Commons Recommended Citation Katie Zoglin, Paraguay's Archive of Terror: International Cooperation and Operation Condor, 32 U. Miami Inter-Am. L. Rev. 57 (2001) Available at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umialr/vol32/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Inter- American Law Review by an authorized administrator of Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PARAGUAY'S ARCHIVE OF TERROR: INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AND OPERATION CONDOR* KATIE ZOGLIN' I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 58 II. POLITICAL CONTEXT .................................................................................... 59 III. OVERVIEW OF PARAGUAY'S ARCHIVE OF TERROR ..................................... 61 A. Discovery Of The Archive Of Terror ...................................................... 61 B. Overview Of The Archive's Contents ....................................................... 63 IV. EVIDENCE OF OPERATION CONDOR IN THE ARCHIVE OF TERROR .............. 64 A. InternationalIntelligence Conferences -

Fortín Boquerón: a Conflict Landscape Past and Present

Fortín Boquerón: a conflict landscape past and present Esther Breithoff* Abstract Similarly to the First World War, the lesser known Chaco War, fought between Paraguay and Bolivia (1932-1935), is a conflict characterised by the excesses of twentieth century ‘supermodernity’. The physical and emotional traces of the Chaco War are numerous, yet academic studies have previously concentrated on the latter’s military history as the centre of their attention. It is the aim of this paper to introduce the potential for an archaeological and anthropological analysis of the Chaco War, thereby using Fortín Boquerón as a means of exemplification. Many of the fortines or military posts, which during the years of conflict constituted crucial focal points in the Chaco landscape, have survived into the present day. Fortín Boquerón represented the setting for one of the most legendary and gruelling battles of the war in question. Partially restored and turned into a tourist attraction throughout the course of the past twenty years, it has now evolved into an invaluable site of interest for the multi- disciplinary investigation techniques of modern conflict archaeology. Keywords: Archaeology. Chaco War. Conflict landscape. Cadernos do CEOM - Ano 26, n. 38 - Patrimônio, Memória e Identidade ‘Supermodernity’ in the form of industrialised warfare during the First World War has shaped the twentieth century. With horror man had to realise that he was no longer in control of himself or the machines he had created. All of a sudden ‘the dream of reason’ had produced monsters (González-Ruibal 2006: 179) and had turned into a global nightmare of ‘excesses’ and ‘supermodern exaggeration’ (González-Ruibal 2008: 247). -

Flags and Banners

Flags and Banners A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton Contents 1 Flag 1 1.1 History ................................................. 2 1.2 National flags ............................................. 4 1.2.1 Civil flags ........................................... 8 1.2.2 War flags ........................................... 8 1.2.3 International flags ....................................... 8 1.3 At sea ................................................. 8 1.4 Shapes and designs .......................................... 9 1.4.1 Vertical flags ......................................... 12 1.5 Religious flags ............................................. 13 1.6 Linguistic flags ............................................. 13 1.7 In sports ................................................ 16 1.8 Diplomatic flags ............................................ 18 1.9 In politics ............................................... 18 1.10 Vehicle flags .............................................. 18 1.11 Swimming flags ............................................ 19 1.12 Railway flags .............................................. 20 1.13 Flagpoles ............................................... 21 1.13.1 Record heights ........................................ 21 1.13.2 Design ............................................. 21 1.14 Hoisting the flag ............................................ 21 1.15 Flags and communication ....................................... 21 1.16 Flapping ................................................ 23 1.17 See also ............................................... -

Cessna 210 Centurion (Cessna-210.Pdf)

18850 Adams Ct Phone: 408/738-3959 Morgan Hill, CA 95037 Toll Free (U.S.): 800/777-6405 www.AircraftCovers.com Fax: 408/738-2729 Email: [email protected] manufacturer of the finest custom-made aircraft covers Tech Sheet: Cessna 210 Centurion (cessna-210.pdf) Cessna 172 Bird Nest Problem Cessna 172 Bird Nest Problem Section 1: Canopy/Cockpit/Fuselage Covers Canopy Covers help reduce damage to your airplane's upholstery and avionics caused by excessive heat, and they can eliminate problems caused by leaking door and window seals. They keep the windshield and window surfaces clean and help prevent Technical Sheet: Cessna 210 Centurion Page 1 vandalism and theft. The Cessna 210 Centurion Canopy Cover is custom designed and fit for each model as well as your aircraft's specific antenna and possible temperature probe placements. The Canopy Cover is designed to enclose the windshield, side and rear window area. The Canopy Cover is a one-piece design, which wraps around the canopy and closes with Velcro behind the pilot's side door. The Velcro closure allows entry to the airplane without removing the entire cover. The Canopy Cover also attaches by two belly straps, one under the engine cowling and one under the tailboom. Belly straps are adjustable and detachable from either side using heavy- duty quick release plastic buckles. The buckles are padded to prevent scratching. To ensure the most secure fit, high-quality shock cord is enclosed in the hem of the cover to help keep the cover tighter against the airplane. Canopy Covers are commonly referred to as Cabin Covers, Fuselage Covers, Canvas Covers, etc. -

Aircraft Library

Interagency Aviation Training Aircraft Library Disclaimer: The information provided in the Aircraft Library is intended to provide basic information for mission planning purposes and should NOT be used for flight planning. Due to variances in Make and Model, along with aircraft configuration and performance variability, it is necessary acquire the specific technical information for an aircraft from the operator when planning a flight. Revised: June 2021 Interagency Aviation Training—Aircraft Library This document includes information on Fixed-Wing aircraft (small, large, air tankers) and Rotor-Wing aircraft/Helicopters (Type 1, 2, 3) to assist in aviation mission planning. Click on any Make/Model listed in the different categories to view information about that aircraft. Fixed-Wing Aircraft - SMALL Make /Model High Low Single Multi Fleet Vendor Passenger Wing Wing engine engine seats Aero Commander XX XX XX 5 500 / 680 FL Aero Commander XX XX XX 7 680V / 690 American Champion X XX XX 1 8GCBC Scout American Rockwell XX XX 0 OV-10 Bronco Aviat A1 Husky XX XX X XX 1 Beechcraft A36/A36TC XX XX XX 6 B36TC Bonanza Beechcraft C99 XX XX XX 19 Beechcraft XX XX XX 7 90/100 King Air Beechcraft 200 XX XX XX XX 7 Super King Air Britten-Norman X X X 9 BN-2 Islander Cessna 172 XX XX XX 3 Skyhawk Cessna 180 XX XX XX 3 Skywagon Cessna 182 XX XX XX XX 3 Skylane Cessna 185 XX XX XX XX 4 Skywagon Cessna 205/206 XX XX XX XX 5 Stationair Cessna 207 Skywagon/ XX XX XX 6 Stationair Cessna/Texron XX XX XX 7 - 10 208 Caravan Cessna 210 X X x 5 Centurion Fixed-Wing Aircraft - SMALL—cont’d. -

Paraguay Investment Guide 2019-2020 Summary

PARAGUAY INVESTMENT GUIDE 2019-2020 SUMMARY Investments and Exports Network of paraguay - REDIEX EDUCATION AND HEALTH IN COUNTRY TRAITS LEGAL FRAMEWORK PARAGUAY 1.1. Socio-economic, political and 4.1. Tax Regime 7.1. Education Services geographical profile 4.2. Labor System 7.2. Professional and Occupational 1.2. Land and basic infrastructure 4.3. Occupational health and safety Training Av. Mcal. López 3333 esq. Dr. Weiss 1.3. Service Infrastructure policies of covid-19 7.3. Health Services Asunción - Villa Morra 1.4. Corporate structure 4.4. Immigration Laws 1 4 7 Paraguay. Page. 9 1.5. Contractual relations between Page. 101 4.5. Intellectual Property Page. 151 Tel.: +595 21 616 3028 +595 21 616 3006 foreign companies and their 4.6. Summary of procedures and [email protected] - www.rediex.gov.py representatives in Paraguay requirements to request the foreign 1.6. Economy investor’s certification via SUACE Edition and General Coordination 4.7. Environmental legislation Paraguay Brazil Chamber of Commerce REAL ESTATE MARKET MAJOR INVESTMENT SECTORS IMPORT AND EXPORT OF GOODS 8.1. Procedure for real estate purchase 8.2. Land acquisition by foreigners 2.1. General Information 5.1. Regulatory framework for interna- Av. Aviadores del Chaco 2050, Complejo World Trade Center Asunción, 2.2. Countries investing in Paraguay tional trade Torre 1, Piso 14 Asunción - Paraguay 2.3. Investment sectors 5.2. Customs 8 Page. 157 Tel.: +595 21 612 - 614 | +595 21 614 - 901 2.4. Investments 5.3. Customs broker [email protected] - www.ccpb.org.py 2 5 5.4. -

EU Ramp Inspection Programme Annual Report 2018 - 2019

Ref. Ares(2021)636251 - 26/01/2021 Flight Standards Directorate Air Operations Department EU Ramp Inspection Programme Annual Report 2018 - 2019 Aggregated Information Report (01 January 2018 to 31 December 2019) Air Operations Department TE.GEN.00400-006 © European Union Aviation Safety Agency. All rights reserved. ISO9001 Certified. Proprietary document. Copies are not controlled. Confirm revision status through the EASA-Internet/Intranet. An agency of the European Union Page 1 of 119 EU Ramp Inspection Programme Annual Report 2018 - 2019 EU Ramp Inspection Programme Annual Report 2018 - 2019 Aggregated Information Report (01 January 2018 to 31 December 2019) Document ref. Status Date Contact name and address for enquiries: European Union Aviation Safety Agency Flight Standards Directorate Postfach 10 12 53 50452 Köln Germany [email protected] Information on EASA is available at: www.easa.europa.eu Report Distribution List: 1 European Commission, DG MOVE, E.4 2 EU Ramp Inspection Programme Participating States 3 EASA website Air Operations Department TE.GEN.00400-006 © European Union Aviation Safety Agency. All rights reserved. ISO9001 Certified. Proprietary document. Copies are not controlled. Confirm revision status through the EASA-Internet/Intranet. An agency of the European Union Page 2 of 119 EU Ramp Inspection Programme Annual Report 2018 - 2019 Table of Contents Executive summary ........................................................................................................................................... 5 1 Introduction -

Terrorist and Organized Crime Groups in the Tri-Border Area (Tba) of South America

TERRORIST AND ORGANIZED CRIME GROUPS IN THE TRI-BORDER AREA (TBA) OF SOUTH AMERICA A Report Prepared by the Federal Research Division, Library of Congress under an Interagency Agreement with the Crime and Narcotics Center Director of Central Intelligence July 2003 (Revised December 2010) Author: Rex Hudson Project Manager: Glenn Curtis Federal Research Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 205404840 Tel: 2027073900 Fax: 2027073920 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://loc.gov/rr/frd/ p 55 Years of Service to the Federal Government p 1948 – 2003 Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Tri-Border Area (TBA) PREFACE This report assesses the activities of organized crime groups, terrorist groups, and narcotics traffickers in general in the Tri-Border Area (TBA) of Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay, focusing mainly on the period since 1999. Some of the related topics discussed, such as governmental and police corruption and anti–money-laundering laws, may also apply in part to the three TBA countries in general in addition to the TBA. This is unavoidable because the TBA cannot be discussed entirely as an isolated entity. Based entirely on open sources, this assessment has made extensive use of books, journal articles, and other reports available in the Library of Congress collections. It is based in part on the author’s earlier research paper entitled “Narcotics-Funded Terrorist/Extremist Groups in Latin America” (May 2002). It has also made extensive use of sources available on the Internet, including Argentine, Brazilian, and Paraguayan newspaper articles. One of the most relevant Spanish-language sources used for this assessment was Mariano César Bartolomé’s paper entitled Amenazas a la seguridad de los estados: La triple frontera como ‘área gris’ en el cono sur americano [Threats to the Security of States: The Triborder as a ‘Grey Area’ in the Southern Cone of South America] (2001). -

Download Print Version (PDF)

Captain Gary Prado Salmón on parade with B Company 2nd Ranger Battalion. “The ‘Haves and Have Nots’: U. S. & Bolivian Order of Battle” By Kenneth Finlayson 40 Veritas they arrived in Guatemala Belize Bolivia in April 1967, U.S. SOUTHERN When Honduras the 8th Special Forces Group Mobile COMMAND Training Team (MTT) commanded El Salvador Nicaragua by Major (MAJ) Ralph W. “Pappy” Shelton was literally the “tip of the Costa Rica Guyana Venezuela spear” of the American effort to Panama Suriname support Bolivia in its fight against a French Guiana Cuban-sponsored insurgency. The 16 men Colombia represented a miniscule economy of force for the 1.4 million-man U.S. Army in 1967 that was fighting in South Vietnam and which was the Ecuador bulk of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) forces defending Europe against the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact. In stark contrast was the Bolivian Army, a 15,000-man force of ill-trained conscripts with out-moded equipment, threatened by Brazil an insurgency. This friendly order of battle article will Peru look at the United States Army forces, in particular those units and missions supporting the U.S. strategy in Latin Bolivia America. It will then examine the Bolivian Armed Forces after the 1952 Revolution and the state of the Bolivian Army Chile when MAJ Shelton and his team arrived to train the 2nd Ranger Paraguay Battalion. It was clearly a case of the “Haves and Have-nots.” The United States Army of 1967 was a formidable force of thirteen infantry divisions, four armored divisions, one cavalry division, four separate infantry brigades, and an armored cavalry regiment.1 In the Argentina Continental United States (CONUS) were two divisions (the 82nd Airborne and the 2nd Armored Division). -

The Jesuit College of Asunción and the Real Colegio Seminario De San Carlos (C

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/91085 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications The Uses of Classical Learning in the Río de la Plata, c. 1750-1815 by Desiree Arbo A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classics and Ancient History University of Warwick, Department of Classics and Ancient History September 2016 ii Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES ...........................................................................................................V LIST OF TABLES .............................................................................................................V ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................. VI DECLARATION AND INCLUSION OF MATERIAL FROM A PREVIOUS PUBLICATION ............................................................................................................ VII NOTE ON REFERENCES ........................................................................................... VII ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................