Culturally Modified Trees of the Nechako Valley Wapato (Part II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modified Trees As Waypoints in the Dena'ina Cultural Landscape, Alaska

Portland State University PDXScholar Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations Anthropology 2020 “Their Markers as they Go”: Modified rT ees as Waypoints in the Dena’ina Cultural Landscape, Alaska Douglas Deur Portland State University, [email protected] Jamie Hebert Portland State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/anth_fac Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the Indigenous Studies Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Deur, D., Evanoff, K., & Hebert, J. (2020). “Their Markers as they Go”: Modified rT ees as Waypoints in the Dena’ina Cultural Landscape, Alaska. Human Ecology, 48(3), 317-333. This Article is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Human Ecology https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-020-00163-3 “Their Markers as they Go”: Modified Trees as Waypoints in the Dena’ina Cultural Landscape, Alaska Douglas Deur1 & Karen Evanoff2 & Jamie Hebert1 # The Author(s) 2020 Abstract The Inland Dena’ina, an Athabaskan people of south-central Alaska, produce and value Culturally Modified Trees (CMTs) in myriad ways. Ethnographic interviews and field visits conducted with Inland Dena’ina residents of the village of Nondalton, Alaska, reveal the centrality of CMTs in the creation and valuation of an Indigenous cultural landscape. CMTs serve as waypoints along trails, as Dena’ina people travel across vast distances to hunt wide-ranging caribou herds and fish salmon ascending rivers from Bristol Bay. -

The Significance and Management of Culturally Modified Trees Final Report Prepared for Vancouver Forest Region and CMT Standards Steering Committee

The Significance and Management of Culturally Modified Trees Final Report Prepared for Vancouver Forest Region and CMT Standards Steering Committee by Morley Eldridge Millennia Research Ltd editorial consultant: Michael Nicoll Yagulaanas January 13, 1997 _______________________________________________________________________________________ Millennia Research 1 Significance Assessment Final Report of Culturally Modified Trees Table of Contents List of Tables............................................................................................................................iii List of Figures..........................................................................................................................iii Acknowledgements..................................................................................................................iii PURPOSE.................................................................................................................................1 PREAMBLE..............................................................................................................................1 BACKGROUND.......................................................................................................................1 CMT Management in the United States................................................................................3 CMT Management in British Columbia...............................................................................4 The Heritage Conservation Act......................................................................................................5 -

First Nations' Perspectives

Clayoquot Sound Scientific Panel Trigger Type Type First Nations’ Perspectives Relating to Forest Practices Standards in Clayoquot Sound First Nations’ Perspectives Relating to Forest Practices Standards in Clayoquot Sound Sydney R. Clayoquot Sound Study Area Megin R. included in Hesquiat Bedwell R. Study Area Harbour Moyeha R. Hesquiat not included in Hot Ursus R. Study Area Springs Cove Flores 0 5 10 15 20 N Island km Cypre R. Ahousat P Bulson Cr. Herbert Inlet Tofino Cr. a Tranquil Cr. Vargas Opitsat c Island Clayoquot R. Meares Kennedy R. i Tofino Island f Tofino Inlet i Vancouver Islandc Kennedy O Lake c e Clayoquot a Sound n Ucluelet Study Area Source: Province of British Columbia (April 1993). Clayoquot Sound Land Use Decision: Key Elements. March 1995 i Clayoquot Sound Scientific Panel Trigger Type Type First Nations’ Perspectives Relating to Forest Practices Standards in Clayoquot Sound March 1995 ii Clayoquot Sound Scientific Panel Trigger Type Type First Nations’ Perspectives Relating to Forest Practices Standards in Clayoquot Sound Table of Contents Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................... v Executive Summary...................................................................................................... vii 1.0 Introduction........................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Context of this Report ................................................................................... -

Culturally Modified Tree (CMT) Management in Nlaka'pamux Territory: Shaping First Nations Participation Through Consultation

Culturally Modified Tree (CMT) Management in Nlaka'pamux Territory: Shaping First Nations Participation through Consultation by Pamela A. Perreault B.Sc. (Hons), University of Waterloo, 1996 A THESIS SUMBITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER' OF SCIENCE in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES THE FACULTY OF FORESTRY Department of Forest Resources Management We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 2002 UBC © Pamela A. Perreault, 2002 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date (\p\\'2Jo]i 2002- ABSTRACT First Nations people have collected life-sustaining materials provided by the forests of British Columbia since time immemorial. In particular, evidence of collection activities from cedar ()is found in the form of culturally modified trees (CMTs). Today, CMTs are considered archaeological resources because of their value as visible indicators of past forest use. Therefore, under provincial legislation (British Columbia Heritage Conservation Act, and the Forest Practices Code Act), they are managed during forest development planning. The value of CMTs extends beyond their contribution to the archaeological record, however, to include: a) legal evidence of Aboriginal rights and title and b) symbols of cultural practices centered around the respect for, and understanding of, people's relationship with nature. -

Plant Management Systems of British Columbia's First Peoples

Portland State University PDXScholar Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations Anthropology 9-2013 Plant Management Systems of British Columbia's First Peoples Nancy J. Turner University of Victoria Douglas Deur Portland State University, [email protected] Dana Lepofsky Simon Fraser University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/anth_fac Part of the Anthropology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Turner, N. J., Lepofsky, D., & Deur, D. (2013). Plant Management Systems of British Columbia’s First Peoples. BC Studies: The British Columbian Quarterly, (179), 107-133. This Article is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. PLANT MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS OF BRITISH COLUMBIA’S FIRST PEOPLES Nancy J. Turner, Douglas Deur, and Dana Lepofsky INTRODUCTION But, see, … people didn’t believe that we did this; they think that Nature just grows on its own. But our people felt, to get more harvest, and a bigger … berry, they did these things. Same thing … a farmer does. (Dr. Daisy Sewid-Smith, Mayanilth, Kwakwaka’wakw, interview with NT, 1 November 1996) nthropologists and archaeologists have traditionally categorized First Nations of British Columbia as “hunter- gatherers” who relied primarily on wild plant and animal foods and did not actively manage food species and their habitats (Duff 1997; A 1999 Ames and Maschner ). However, in the last decade, as a result of research conducted by ethnobotanists and others working closely with Indigenous ecological knowledge holders, there is more widespread understanding that plant and animal use involved complex management traditions. -

Rediscovering a Petroglyph in the High Cascades Volume 54 David A

Journal Anthropology of Northwest Fall 2020 Volume 54 J ournal Number 2 O f N orthwest A nthropology “No One Asked for an Ethnography.” Reflections on Community-based Anthropology in Coast Salish Country N Thomas W Murphy 145 Image Rock: Rediscovering a Petroglyph in the High Cascades Volume 54 Volume David A. Kaiser and Julia Cleary 165 Coast Salish Social Complexity, Community Ties, and Resistance: Using Mortuary Analysis to Identify Changes in Coast Salish Society Before, During, and After the Early Number 2 Number Colonial Period Alexandra M. Peck 175 Confirmation Bias: Commentary on the 2020 JONA Article, “Salish Sea Islands Archaeology and Precontact History” Adam N. Rorabaugh, Kate Shantry, and James W. Brown 203 Historical Archaeology of Fort Boise’s Surgeon’s Quarters Porch Evidences the Behavior of Children Nathan J. May 240 Abstracts from the 72nd Annual Northwest Anthropological Conference, Kennewick, Washington, 20–23 March 2019 264 Journal of Northwest Anthropology List of Reviewers 2018–2019 278 Fall 2020 Fall W Journal of Northwest Anthropology Volume 54, Number 2 Fall 2020 CONTENTS Volume 54, Number 1 Volume 54, Number 2 1 “La Gente de Washington es la Más 145 “No One Asked for an Ethnography.” Tranquila” (People from Washington are Reflections on Community-based the Most Laid-Back): An Ethnographic Anthropology in Coast Salish Country Perspective on Honduran and Salvadoran Thomas W Murphy Migration to the Pacific Northwest Jordan Levy and Sandra Estrada 165 Image Rock: Rediscovering a Petroglyph in the High Cascades 22 Salish Sea Islands Archaeology and David A. Kaiser and Julia Cleary Precontact History Richard M. -

Satchie Creek's Cmts

A Reconnaisance of Satchie Creek’s Hesquiaht Culturally Modified Trees By David Black, Stephen Charleson, Karen Charleson, James Cole, Nan Macy, Dennis Morgan, David Silverberg, and Sarah Tyne On 5 August, 2007, Hooksum Outdoor School and Environmental Learning Institute, conducted a reconnaissance expedition in Satchie Creek watershed to assess the creek’s physical fish quality and the presence of culturally modified trees. Satchie Creek is in the Yaksis Hahoutley of the Hesquiaht First Nation of Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations. The Hesquiaht First Nation’s territory is in the northern Clayoquot Sound on the west side of Vancouver Island. In the midst of decades of controversial treaty and land use negotiations, the Clayoquot Sound Watershed was declared a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in January 2000. Biosphere designation recognizes global appreciation of Clayoquot sound’s exceptional natural and cultural values and attributes. One example of these values and attributes are the rare watersheds in cultural old growth conditions. Satchie Creek watershed is one of two remaining culturally modified old growth coastal temperate rainforest drainages in the Hesquiaht Lake watershed. Satchie Creek watershed is approximately 2500 hectares. At the Hesquiaht Lake outlet, Satchie Creek is a third order creek with 4 significant 2nd order sub-watersheds. In the Hesquiaht Harbor watershed, a culturally modified tree is a tree that has been altered by Hesquiaht people as a part of their traditional use of the forest. There are many kinds of culturally modified trees in the Hesquiaht watershed. Examples include trees with bark removed, stumps and felled for logs, trees tested for soundness, trees with scars from plank removal, relict wedges and trees cut for wood or kindling. -

Radical Ecology, the Fourth Woeud and Local Identity in the Bella Coola Region

"THEY'VE GOT NO STAKE IN -RE THEY'RE AT": RADICAL ECOLOGY, THE FOURTH WOEUD AND LOCAL IDENTITY IN THE BELLA COOLA REGION by WILLIAM T.L. HIPWELL, B.A. A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Geography CarIeton University Ottawa, Ontario May 20. 1997 Q copyright 1997 William T.I.. Hipwell National tibrary Bibliothèque nationale I*I of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibiiographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellingtori ûüawaON K1AON4 Oaawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Vwr file Votre rd- Our Me None rBfBn)nte The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distri'bute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfichelfilm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels rnay be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract The Forest Action Network. a radical environmental group. began in 1995 a co- operative relationship with "the House of Srnayusta*: a faction of the Nuvalk First Nation. -

Modified Trees

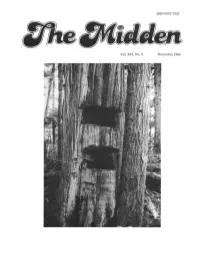

ISSN 0047-7222 Vol. XVI, No. 5 December 1984 The Midden Publication of the Archaeological Society of British Columbia Editor: Kathryn Bernick Address: P.O. Box 520, Station A, Vancouver, B.C. V6C 2N3. Submissions and exchange publications should be directed to the Editor. Contributions on subjects germane to B.C. Archaeology are welcomed: maximum length 1,500 words, no footnotes and only a brief bibliography (if necessary at all) . Guidelines available. The contents of The Midden are copyrighted by the A.S.B.C. It is unlawful to reproduce all or part by any means whatsoever, without permission of the Society, which is usuall y gladly given. Subscription is by membership in the A.S.B.C ., or $8.00 a year (5 issues). The next issue of The Midden will appear mid-February, 1985. Publication of The Midden is made possible in part by a grant from the British Columbia Heritage Trust. THE COVER : Two "test holes" in a cedar tree at an aboriginal logging and canoe manufacturing site (FkUb 7/ on the Queen Charlotte Islands. The holes were cut with an axe in 1869. Photo courtesy of the B.C. Heritage Conservation Branch. The Society Membership year runs September 1-August 31. Fees: single - $15; family - $17; senior citizen - $10; student - $10. Address to : A.S.B.C. Membership Secretary, Box 520, Station A, Vancouver, B.C. V6C 2N3. Meetings featuring illustrated lectures are held on the second Wednesday of each month (except July and August), at 8:00 p.m. in the Vancouver Museum Auditorium. Visitors and new members are welcome! Coming Topics : January 9 Dr. -

Theory and Practice from the Cultural Rainforests of Kitasoo/Xai’Xais Territory

Biocultural approaches to environmental management and monitoring: theory and practice from the cultural rainforests of Kitasoo/Xai’xais Territory by Bryant DeRoy B.Sc., University of British Columbia, 2013 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in the Department of Geography ÓBryant DeRoy, 2019 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. Biocultural approaches to environmental management and monitoring: theory and practice from the cultural rainforests of Kitasoo/Xai’xais Territory by Bryant DeRoy B.Sc., University of British Columbia, 2013 Supervisory Committee: Dr. Christopher Darimont (Department of Geography) Supervisor Dr. Christopher Bone (Department of Geography) Committee Member Dr. Iain McKechnie (Department of Anthropology) Outside Member ii Abstract Biocultural approaches to Environmental Management (EM) and monitoring are an emerging strategy in sustainability planning. Unlike functional ecological approaches to EM, which exclude humans from ecological systems, biocultural EM approaches incorporate humans, communities and their values as integral part of ecological systems, and are grounded in collaborative processes that develop locally relevant management objectives and monitoring practices. Biocultural indicators are a key aspect of biocultural EM, providing links between worldviews, knowledge systems, agencies and institutions at various scales to guide and streamline implementation of management objectives. Although many Indigenous Peoples have been continually practicing biocultural approaches to EM for thousands of years, challenges exist in contemporary EM scenarios where multiple worldviews, political boundaries and knowledge systems collide. Some of the challenges or gaps in contemporary biocultural approaches are based in theory, and others are in practice. -

Red Cedar (Thuja Plicata) Is Found in the Temperate Coastal Rainforests of North America. Meares Island. Adrian Dorst Photo

Red cedar (Thuja plicata) is found in the temperate coastal rainforests of North America. Meares Island. Adrian Dorst photo. AA VanishingVanishing Heritage:Heritage: The Loss of Ancient Red Cedar from Canada’s Rainforests Author Note John Nelson has over 10 years experience researching forestry and environmental policy. Also contributing to this report were: Cheri Burda, Jean Kavanagh and Bill Wareham of the David Suzuki Foundation, and Andrea Reimer of the Western Canada Wilderness Committee. The Western Canada Wilderness Committee is Canada's largest membership- based citizen-funded wilderness preservation organization. We work for the preservation of Canadian and international wilderness through research and grassroots education. The Wilderness Committee works on the David Suzuki Foundation ground to achieve ecologically sustainable The David Suzuki Foundation is a registered communities. We work only through lawful Canadian charity that works through science means. and education to protect the balance of nature and our quality of life, now and for future generations. 02 | Vanishing Cedar A Vanishing Heritage: The Loss of Ancient Red Cedar from Canada’s Rainforests Introduction 05 Western Red Cedar • Cultural and Ecological Heritage 06 • Cultural Traditions and Wealth 07 Logging Red Cedar: History and Current Status • Targeting Cedar 08 • Summary of Analysis (Table) 10 • Methodology 11 • High Grading 13 • Trade and Tariffs 15 • Prices and Markets 15 Effects of Cedar High Grading • Cultural Impacts 16 • CMTs and the Courts 16 • Ecological Impacts 18 • Bear Den Case Study 19 • Species at Risk 20 • Economic Impacts 22 Conclusion 24 Recommendations 25 Appendix 1: Methodology and Sources 26 Appendix 2: Cedar Raw Log Exports 28 Appendix 3: Open Markets 29 Endnotes 31 Red cedar. -

Wapato and Katzie First Nation Pinto Flats - Field Schools 2002- Field Reports Permits

TilE• Publication of the Archaeological Society of British Columbia ISSN 0047-7222 Vol. 33, No. 4 - 2001 Wapato and Katzie First Nation Pinto Flats - Field Schools 2002- Field Reports Permits SERIALS SERVICES RECEIVED JUN -6 2002 UNIVERSITY OF VICTORIA McPHERSON LIBRARY • ' ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF &MIDDEN BRITISH COLUMBIA Published four times a year by the Dedicated to the protection of archaeological resources Archaeological Society of British Columbia and the spread of archaeological knowledge. Editorial Committee President Editor: Heather Myles (604.274.4294) Andrew Mason (604.874.9221) heathermyles@ shaw.ca andrew_mason@ golder.com Assistant Editor: Helmi Braches (604.462.8942) Membership braches@ attcanada.ca Permit Lists: Richard Brolly (604.689.1678) Bev Liddle (604.986.6543) rbrolly@ arcas.net [email protected] Heather Myles News Editor: Annual membership includes a year's subscription to Field Editor: vacancy The Midden and the ASBC newsletter, SocNotes. Publications Editor: Monica Karpiak: (604.294.3394) mkarpiak:@ sfu.ca Membership Fees Production & Subscriptions: Individual: $25 Family: $30 Seniors/Students: $18 Fred Braches (604.462.8942) braches@ attcanada.ca Send cheque or money order payable to tJ;le ASBC to: SUBSCRIPTION is included with ASBC membership. ASBC Memberships Non-members: $14.50 per year ($17.00 USA and overseas), P.O. Box 520, Bentall Station payable in Canadian funds to the ASBC. Remit to: Vancouver BC V6C 2N3 Midden Subscriptions, ASBC ASBC on Internet P.O. Box 520, Bentall Station Vancouver BC V6C 2N3 http://asbc.bc.ca SUBMISSIONS: We welcome contributions on subjects germane to BC archaeology. Guidelines are available on request. Submis sions should be directed to the appropriate editor at the ASBC Branches address.